The importance of the Yusupov family in the 18th century. Princes Yusupov. What have you done, roast goose?

Princes Yusupov

Vladimir Polushko

In terms of nobility they were not inferior to the Romanovs, and in terms of wealth they were significantly superior to them. The Yusupov family began in 1563, when two sons of the ruling prince of the Nogai Horde, Il-Murza and Ibrahim-Murza, arrived in Moscow.

Tsar Ivan IV received them favorably and endowed them with rich estates “according to the nobility of the family.” The line of descendants of Ibrahim Murza ended early. The younger brother Il-Murza died in 1611, bequeathing his five sons to faithfully serve Russia. His grandson and heir Abdullah converted to Orthodoxy in 1631 and was named Dmitry Yusupov. Instead of the Tatar name “Murza”, he received the title of prince and royal charters for hereditary ownership of new estates. The first prince Yusupov was granted the title of steward and was appointed to voivodeship and ambassadorial positions. He significantly increased the family wealth by marrying the rich widow Katerina Yakovlevna Sumarokova, the daughter of the devious Khomutov, who was close to the royal court.

The heir to most of this wealth was their son Grigory Dmitrievich Yusupov (1676 - 1730). He was a companion of Peter I's youth games, and in adult life he became one of the closest associates of the reformer Tsar. Prince Gregory participated in the implementation of all, as we would now say, “projects” of Peter I and, of course, hastened with him to the banks of the Neva to open a “window to Europe.” So the history of the St. Petersburg branch of the Yusupov family began simultaneously with the history of our city. Prince Gregory was the organizer of the Russian galley fleet, a member of the State Military Collegium. At the burial of Peter the Great, only the three state dignitaries closest to him followed immediately behind the coffin. These were A.D. Menshikov, F.M. Apraksin and G.D. Yusupov.

The heir of Grigory Yusupov, his son Boris Grigorievich (1695 - 1759), can also be considered a “chick of Petrov’s nest”. Among a group of young noble offspring, he was sent by Peter to study in France, and successfully graduated from the Toulon School of Midshipmen. During the reign of “Petrova’s daughter” Elizabeth, he held a number of high government positions: he was director of the Ladoga Canal, president of the Commerce Collegium.

Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov (1750 – 1831) achieved even more noticeable success in public service. He was a member of the State Council, a diplomat of the highest rank, communicated with kings and emperors, met with Voltaire, Diderot, Beaumarchais. As the supreme marshal of the coronation, he led the crowning ceremony of three Russian emperors: Paul I, Alexander I and Nicholas I. On the instructions of Catherine II, Nikolai Borisovich collected artistic works from the best masters throughout Europe for the imperial collection. At the same time, he began to collect his own collection, which over time became one of the best private collections of works of art not only in Russia, but throughout Europe. According to contemporaries, Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov was one of the most truly noble and cultured people of his time, without the slightest hint of stupid arrogance. It was to him that A.S. Pushkin dedicated the poem “To the Nobleman.”

The grandson of the “enlightened nobleman,” named after the legendary grandfather Nikolai Borisovich Jr. (1827 – 1891), at the age of 28 he was the commander-in-chief of the coronation ceremony of Alexander II. But in addition to honorary duties and high titles, he inherited from his grandfather a creative nature, a subtle artistic taste, and a passion for collecting and philanthropy. Nikolai Borisovich himself was no stranger to communicating with muses. He was fond of playing music and studied composition. His sonatas, nocturnes and romances were performed not only in St. Petersburg halls, but also in music salons in other European cities. He also paid tribute to literary creativity: he wrote novels and religious and philosophical treatises. N.B. Yusupov's books are stored in the former Imperial Public Library, of which he was vice-director for four years.

N.B. Yusupov Jr. became the last representative of an ancient family in the direct male line - he died without leaving any male heirs. Several years before his death, he received the highest permission to transfer the surname, title and coat of arms to the husband of his eldest daughter Zinaida, Count F.F. Sumarokov-Elston, and then to their descendants. To the credit of the Yusupovs, it should be noted that back in 1900 (that is, long before the coming catastrophic upheavals), a will was drawn up, according to which, in the event of the termination of the family, all artistic values become the property of the state and remain in Russia.

Zinaida Nikolaevna Yusupova (1861 – 1939) completes the series of spiritually beautiful women who have graced the Yusupov family for centuries. We can judge their beauty by ancient portraits created by the best artists. The portrait of Zinaida Nikolaevna was painted by the great Valentin Serov, who managed to convey to us his admiration for the spiritual and physical beauty of this woman. Next to this portrait in the Russian Museum hangs a portrait of her son Felix, created in the same 1903.

Prince Felix Yusupov, Count Sumarokov-Elston (1887 - 1967) became the most famous of the Yusupov family, although he did not perform any feats of arms and did not distinguish himself in public service. At the beginning of the twentieth century, he was the idol of St. Petersburg's golden youth, had the nickname Russian Dorian Gray, and remained an admirer of Oscar Wilde throughout his life. In 1914, Felix married Grand Duchess Irina (Note from the site keeper: Irina Alexandrovna wore the title of Princess of the Imperial Blood), the Tsar’s niece. The Yusupovs became related to the Romanovs three years before the collapse of the dynasty. In December 1916, Felix became the organizer of a monarchist conspiracy, as a result of which Grigory Rasputin was killed in the family mansion on the Moika. The conspirators were sure that they were acting to save the Russian Empire. In fact, the murder of Rasputin only accelerated the inevitable collapse of the three-hundred-year-old dynasty and the subsequent revolutionary upheavals.

In emigration, the Yusupovs learned for the first time in the centuries-old history of their family what it meant to make a living. Felix worked as an artist, wrote and published memoirs. His wife opened a sewing workshop and a fashion salon. During the Great Patriotic War, Felix Yusupov showed real courage and patriotism, decisively rejecting all offers of cooperation from the fascists.

The Yusupovs left Russia in 1919 on board the English dreadnought Marlborough, which was sent for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna by her august nephew King George V. The exile lasted for many decades. Only Felix Feliksovich's granddaughter Ksenia, born in France in 1942, waited to return. In 1991, she first crossed the threshold of the family mansion on the Moika, where the Leningrad Teacher's House was located.

On January 7, 1994, on the landing of the main staircase of the Yusupov Palace, Ksenia Nikolaevna Yusupova-Sfiri met the guests of the Christmas ball, which opened the “St. Petersburg Seasons”. The author of these lines was among those invited. And I remember very well that, despite the proletarian skepticism towards the noble-monarchical traditions (brought up by many years of experience in Soviet journalism), I experienced something similar to sacred awe. It was one of those rare moments when you visibly feel the cyclical nature of history and the fact that it moves, if not in a circle, then in a spiral.

Family tree

In his memoirs written in exile, Felix Yusupov described the history of his family as follows: “It begins with the Tatars in the Golden Horde, continues in the imperial court in St. Petersburg and ends in exile.” His family descended from the Nogai ruler Yusuf. Starting from the era of Peter the Great, the Yusupov princes invariably occupied important government positions (one of them was even the Moscow governor). Over time, the family accumulated enormous wealth. Moreover, each Yusupov had only one son, who inherited the entire fortune of his parents.

The male branch of the Yusupov family died out in 1882

The male offspring of the clan ended in 1882 with Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov. The aristocrat had a daughter, Zinaida, and from her two grandchildren. The elder Nikolai was killed in a duel, after which Zinaida Nikolaevna and her husband Felix Sumarokov-Elston were left with the only heir - Felix Feliksovich. He was born in 1887 and, thanks to an imperial decree, as an exception, received both the surname and property of his mother.

Stormy youth

Felix belonged to the capital's “golden youth”. He received his education at the Gurevich private gymnasium. In 1909 - 1912 the young man studied at Oxford, where he became the founder of the Russian Society at Oxford University. Returning to his homeland, Yusupov headed the First Russian Automobile Club.

In the fateful year of 1914, Felix married Irina Alexandrovna Romanova, the niece of Nicholas II. The emperor personally gave permission for the wedding. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon abroad. There they learned about the beginning of the First World War.

By coincidence, the Yusupovs found themselves in Germany at the most inopportune moment. Wilhelm II gave the order to arrest the unlucky travelers. Diplomats intervened in the situation. At the last moment, Felix and his wife managed to leave the Kaiser’s possessions - if they had delayed even a little longer, they would not have been able to return to their homeland.

The prince was the only son in the family and therefore avoided being sent to the front. He remained in the capital, where he organized the work of hospitals. In 1915, the young couple had their only daughter, Irina. From her come the modern descendants of the Yusupov family.

"Rasputin must disappear"

Living in Petrograd, Yusupov could observe with his own eyes the depressing changes in the mood of the capital. The longer the war dragged on, the more the public criticized the royal family. Everything was remembered: the German family ties of Nicholas and his wife, the indecisiveness of the crown bearer and, finally, his strange relationship with Grigory Rasputin, who treated the heir Alexei. Married to the royal niece, Yusupov perceived the mysterious old man as a personal insult.

In his memoirs, the prince called Rasputin “a satanic force.” He considered the Tobolsk peasant, who practiced strange rituals and was known for his dissolute lifestyle, to be the main cause of Russia's misfortunes. Yusupov not only decided to kill him, but also found loyal accomplices. They were Duma deputy Vladimir Purishkevich and Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich (Felix's brother-in-law).

On the night of December 30, 1916 (new style), Rasputin was invited to the Yusupov Palace on the Moika. According to the established version, the conspirators first fed him a pie poisoned with potassium cyanide, and then the impatient Felix shot him in the back. Rasputin resisted, but received several more bullets. The trio threw his body into the Neva.

Yusupov failed to poison Rasputin with potassium cyanide

It was not possible to hide the crime. With the beginning of the investigation, the emperor ordered Felix to leave the capital to the Kursk estate of Rakitnoye. Two months later, the monarchy fell, and the Yusupovs left for Crimea. After the October Revolution, the princely family (including Felix’s parents) left Russia forever on the British battleship Marlborough.

"All events and characters are fictitious"

“Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental” is approximately the same phrase at the beginning of many films that every film lover sees. Felix Yusupov is directly responsible for the creation of this stamp.

Once in exile, the prince had to learn how to earn money. In the early years, family jewelry helped out. The income from their sale allowed Felix to settle in Paris and, together with his wife, open the fashion house “Irfé” (the name was formed from the first two letters of the names Irina and Felix). In 1931, the emigrant’s business was closed due to unprofitability. And then an opportunity presented itself to Yusupov opportunity to earn money in court.

Although the aristocrat was never held accountable for the massacre of Rasputin, the label of the killer of the Siberian warlock stuck to him for the rest of his life. In the West, interest in “The Russia We Lost” has not subsided for many years. The theme of relations within the crowned Romanov family was also actively exploited. In 1932, the Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced the film Rasputin and the Empress. The tape claimed that Yusupov’s wife was Grigory’s mistress. The offended prince sued the studio for libel. He won the case, receiving a significant sum of 25 thousand pounds. It was after that scandalous lawsuit that MGM (and later throughout Hollywood) began to include the disclaimer “All events and characters are fictitious” in their films.

Felix Yusupov owned the Irfé fashion house

Yusupov lived in his homeland for 30 years, in exile for 50. During the Great Patriotic War, he did not support the Nazis, as many other emigrants did. The prince did not want to return to Soviet Russia after the victory over Hitler. He died in 1967 at the age of 80. The last Yusupov was buried in the Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois cemetery.

If you believe astrologers, in the famous family of Russian princes Yusupov, everyone was born and died in strict accordance with the inevitable laws of Space and Earth, which were in force at the moment when the Voice sounded, placing a curse on their family...

Family coat of arms of the Yusupovs

Deep roots

For a long time, according to some legend, it was believed that the Yusupov family originated from the famous prophet Ali, that is, from Muhammad himself. However, having thoroughly researched the roots of the surname N.B. Yusupov Jr. made significant adjustments in 1866–1867. It turned out that its ancestor Bakr ibn Raik did not live during the time of Muhammad, but three centuries later and was the supreme commander of the Arab caliph Ar-Radi billah Abu-l-Abbas Ahmad ibn Jafar (907–940). Twelve generations of the descendants of the warlike Ibn Raik lived in the Middle East. They were sultans and emirs in Damascus, Egypt, Antioch, Medina, Constantinople, and Mecca. But in the 13th century, the son of Sultan Termes, who ruled in Mecca, and a group of people devoted to him decided to move to the shores of Azov and the Caspian Sea. His famous descendant Edigei (1352–1419) is considered the founder of the Crimean (Nogai) Horde. Under the great-great-grandson of Edigei - Khan Yusuf (1480s - 1555) - the Nogai Khanate reached its greatest prosperity.

Khan Yusuf was killed by his brother Ishmael in February 1555. In order not to take on the sin of killing Yusuf’s sons, Ishmael sent them to the court of Ivan the Terrible. The Russian Tsar graciously met the orphans - Il-Murza and Ibrahim-Murza, generously giving them lands.

The line of descendants of Ibrahim-Murza soon ended. But Il-Murza left five sons after his death in 1611. One of them was Seyush-Murza Yusupov-Knyazhevo. He was a brave warrior, faithfully served the Russian throne both under Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov and under Alexei Mikhailovich. The estates and title of the clan were inherited by his son from his first wife Abdullah (Abdul-Murza). Just like his father, he fought bravely in military campaigns against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate.

What have you done, roast goose!

The baptism of this Russified descendant of Khan Yusuf took place under rather curious circumstances. Once Abdul-Murza hosted Patriarch Joachim and, with the best intentions, treated the Orthodox high priest to roast goose. And the dinner party was during Lent. The Patriarch, not suspecting anything, tasted the modest one, and also praised: “You have a nice fish, prince!” Abdul-Murza remained silent in response. But there was a well-wisher who whispered to the patriarch what kind of fish the infidel Nogai had fed him. Joachim, mortally offended, complained to the king. The pious sovereign, angry, deprived Murza of almost all his estates.

The descendant of Yusuf was in deep thought for a long time and finally decided, by converting to Orthodoxy, to earn the sovereign’s forgiveness and return the taken lands. According to family legend, he made this decision on the third day after the story with the goose, that is, on Easter itself. And that same night he had a vision, or maybe a prophetic dream. In short, he heard a voice: “From now on, for betraying the faith of your ancestors, out of all the children, there will be only one heir left. The rest will die before they reach 26 years of age.”

In 1681, Abdul-Murza was baptized with the name Dmitry Seyushevich. And, as predicted, all his children did die. Except for the youngest son Grigory Dmitrievich. He was five years old when his father changed his faith.

Portrait of Zinaida Yusupova with the family pearl “Pelegrina”.

Artist Francois Flameng. 1894

Whether the family legend is true or not, this story is reflected even in the interiors of Yusupov’s palaces: the lush exterior decorations often contain an image of a goose. True, the legend lives in two versions. According to the second, the clan was cursed by a Nogai sorceress after the Horde learned that the sons of Murza had converted to Christianity. It is interesting that the curse came true in almost every generation and also affected the fate of the bearers of the Yusupov surname and even illegitimate children born from representatives of the princely family.

The secret love of a beautiful great-grandmother

Zinaida Yusupova (nee Naryshkina, 1809–1893) learned about the curse after her marriage and bluntly told her husband, Boris Nikolaevich Yusupov (1794–1849), that she was not going to give birth to dead people, and therefore he was free to “satisfy his lust with the courtyard girls.” But you can’t fool nature, and the young princess herself went into all sorts of troubles. The whole of St. Petersburg was gossiping about her stormy romances. But they especially talked a lot about adultery with the young revolutionary Narodnaya Volya. When her lover ended up in the casemate of the Shlisselburg fortress, Princess Zinaida did the almost impossible: using connections at court, she ensured that the prisoner was released to her on parole.

It is difficult to say how long this fantastic romance lasted. Only years later, after three revolutions, looking for Yusupov’s treasures, representatives of the Soviet authorities knocked on all the walls and searched all the secluded places of the luxurious Naryshkina-Yusupova palace on Liteiny Prospekt in Leningrad. No treasures were found. But in a secret room connected to the princess’s bedroom, the skeleton of a man, wrapped in a shroud, suddenly fell on the security officers.

There were rumors among St. Petersburg old-timers that Yusupova had managed to rescue her lover from captivity (perhaps she simply ransomed him). But the beautiful young man suffered from consumption and did not last long...

Felix Feliksovich Yusupov Jr. (1887–1967) recalled in his memoirs that, while sorting out old papers in her bedroom after the death of his great-grandmother, he experienced inexplicable horror and immediately called a footman, hoping that an evil force - a ghost or spirit - would not appear to the two of them . What was it? The energy of unburied and unbroken ashes, forever hidden in a secret room?..

By the way, according to the Yusupov family legends, the shadows of their deceased ancestors were supposed to be invisibly present in their family nests. It is no coincidence that one of the bearers of an ancient surname, going to a ball or reception, left her caskets and boxes unlocked. She explained it this way: “Let our family spirits admire our family jewels.”

Alexander Pronin

Read the continuation in the February issue (No. 02, 2014) of the magazine “Miracles and Adventures”

Rock of the Yusupov family

There are several versions of legends about the Yusupov family curse. Even within the family, this story was told in different ways. Zinaida Nikolaevna herself adhered to the version of her grandmother - Zinaida Ivanovna Naryshkina-Yusupova-de Chavaud-de-Serre.

The founder of the clan was considered to be the Khan of the Nogai Horde, Yusuf-Murza. Wanting to make peace with Moscow against the will of his fellow tribesmen and fearing for the lives of his sons, he sent them to the court of Ivan the Terrible. The Russian chronicle says: “The sons of Yusuf, having arrived in Moscow, were granted many villages and hamlets in the Romanov district, and the service Tatars and Cossacks settled there were subordinate to them. From that time on, Russia became the fatherland for the descendants of Yusuf.” The old khan calculated everything correctly: before his sons had time to reach Moscow, his brother dealt harshly with him. When the news reached the Horde that the sons of Murza had abandoned the Muslim faith and accepted Orthodoxy, one of the sorceresses placed a curse on them, according to which, out of the total number of Yusupovs born in one generation, only one would live to be twenty-six years old, and so it would continue up to the complete destruction of the dynasty. Why this curse sounded so confusing is not easy to say, but it came true with amazing accuracy. No matter how many children the Yusupovs had, only one man was destined to live to the age of twenty-six.

At the same time, this terrible fate did not affect the financial prosperity of the family in any way. By 1917, the Yusupovs were in second place in wealth after the Romanovs themselves. They owned a huge amount of land, sugar, brick, sawmills, as well as factories and mines. Their annual income was no less than fifteen million gold rubles. And there were legends about the luxurious Yusupov palaces. Even the greatest princes were jealous of the stunning decoration of their houses and salons. For example, Zinaida Nikolaevna’s rooms in Arkhangelskoye and in the palace in St. Petersburg were furnished with designs from the executed French queen Marie Antoinette. The art gallery could compete with the Hermitage in terms of the number of greatest and authentic works by recognized artists. And Zinaida Nikolaevna’s countless jewels were treasures that in the past belonged to almost all the royal courts of Europe. She especially treasured the magnificent pearl “Pelegrina”. She rarely parted with it and is even depicted wearing it in all portraits. It once belonged to Philip II and was considered the main decoration of the Spanish Crown. However, Zinaida Nikolaevna did not measure happiness by wealth, and the curse of the Tatar sorceress made the Yusupovs unhappy.

Of all the Yusupovs, probably only Zinaida Nikolaevna’s grandmother, Countess de Chavo, was able to avoid great suffering due to the untimely death of her children. Born Naryshkina, Zinaida Ivanovna was married to Boris Nikolaevich Yusupov while still a very young girl. Soon she gave birth to a son, and then a daughter who died during childbirth. Only after these events did she learn about the family curse. Being a sensible woman, she told her husband that she would no longer “give birth to dead people.” In response to his objections, she stated that if he still had not had his fill, then he was allowed to “belly the courtyard girls,” and that she was not going to object. This was the case until 1849, when the old prince died.

Zinaida Ivanovna was not even forty years old when she plunged headlong into the maelstrom of new novels and relationships. There were gossip and legends about her beau, but the young Narodnaya Volya received the most attention. When he was imprisoned in the Shlisselburg fortress, the princess abandoned social life, followed him and, unknown how, she achieved that he was released to her at night. Many people knew about this story and gossiped about it, but, surprisingly, Zinaida Ivanovna was not condemned. On the contrary, secular society recognized the right of the stately princess to all sorts of extravagances a la de Balzac. But then it all ended; for some time she was a recluse at Liteiny. Then she married a bankrupt but well-born Frenchman and left Russia, abandoning the title of Princess Yusupova. In France, she was called Countess de Chaveau, Marquise de Serres. The story associated with the young Narodnaya Volya member was recalled by Yusupov after the revolution. One of the emigrant newspapers published a report that, in search of Yusupov’s treasures, the Bolsheviks destroyed all the walls of the palace on Liteiny Prospekt. To their chagrin, they did not find any jewelry, but they did find a secret room adjacent to the bedroom, in which there was a coffin with the body of an embalmed man. This was probably the Narodnaya Volya member sentenced to death, whose body Zinaida Ivanovna bought and brought to St. Petersburg.

However, for all the drama of the life of Zinaida Naryshkina-Yusupova-de Chavaud-de-Serre, her family considered her happy. All her husbands died before reaching old age, and she lost her daughter during childbirth, when she had not yet had time to get used to her. She fell in love many times, did not deny herself anything, and she died surrounded by her family. For the rest of the dynasty, despite their mind-boggling wealth, life was much more prosaic. Family rock spared no one.

Zinaida Nikolaevna's eldest son Nikolenka grew up as a silent and withdrawn boy. No matter how hard Princess Yusupova tried to bring him closer to her, nothing worked for her. All her life she had imagined the horror that gripped her when, at Christmas 1887, when asked to her son what gift he would like to receive, Zinaida Nikolaevna listened to a completely unchildish and icy answer: “I don’t want you to have other children.” "

Then the princess was confused, but it soon became clear that one nanny assigned to the young prince told the boy about the Nogai curse. She was immediately fired, but Zinaida Nikolaevna waited for the expected baby with a feeling of absorbing and acute fear. Even at first, the fears were not in vain. Nikolenka did not hide his dislike for Felix, and only ten years later, between the matured brothers, a feeling arose that was more like friendship than the love of two relatives. Family rock made its presence known in 1908. Then the ill-fated duel took place.

In the memoirs of Felix Yusupov, it is easy to see that throughout his life he was jealous of his mother for Nikolai, who, although outwardly resembled his father rather than Zinaida Nikolaevna, was incredibly similar to her in his inner world. He was also fond of theater, loved music, drew and painted beautifully. He published his stories under the pseudonym Rokov. Even Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, who was stingy with flattering reviews, noted the author’s undoubted talent.

After graduating from St. Petersburg University, he received a law degree. The family was planning the upcoming marriage of the young prince. But the romantic Nicholas, unexpectedly for himself and for everyone, fell in love with Maria Heyden, who at that time was already engaged to Count Arvid Manteuffel, and soon this wedding took place. The young couple went on a trip to Europe, and Nikolai Yusupov did not fail to follow them - a duel was inevitable. And it happened.

On June 22, 1908, on the estate of Prince Beloselsky on Krestovsky Island in St. Petersburg, Count Manteuffel’s hand did not waver and he did not miss. Nikolai Yusupov would have turned twenty-six years old in six months.

“Rending screams were heard from my father’s room,” Felix Yusupov recalled some time later. “I walked in and saw him, very pale, in front of the stretcher where Nikolai’s body was stretched out. His mother, kneeling before him, seemed to have lost her mind. With great difficulty we tore her away from our son’s body and put her to bed. Having calmed down a little, she called me, but when she saw me, she mistook me for her brother. It was an unbearable scene. Then my mother fell into prostration, and when she came to her senses, she did not let me go for a second.”

From the book Book 3. Paths. Roads. Meetings author Sidorov Georgy AlekseevichChapter 31. The legend about the appearance of the Raven clan - Sorry that I distracted you, Nikolai Konstantinovich, I really really want to know about the origin of the Raven clan. Tell me what you promised,” I reminded the Khan of his desire. “Well, then listen and remember,” he leaned back on the deer

From the book Ancient Turks author Gumilev Lev NikolaevichChapter III. CREATION OF THE GREAT POWER OF THE ASHINA CLASS (545-581) The beginning of the history of the ancient Turks (Turkuts). Although the history of every nation goes back to ancient times, historians of all eras have a desire to begin the description from the date that determines (in their opinion) the emergence

From the book The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation: from Otto the Great to Charles V by Rapp FrancisTwo families in the struggle for power. Lothair III of the Welf family (1125–1137) Henry V died without leaving a direct heir. Succession to the throne was not an obvious fact. In this state of affairs, the princes had to find a solution. And they willingly took on such a burden. Already

From the book The Holy Grail and the descendants of Jesus Christ by Gardner LawrenceChapter Thirteen The Secret Conspiracy Against the Family THE CENTURY OF THE SAINTS Being cut off from the Byzantine metropolis, the Church of Rome, around the beginning of the 7th century, gave a completed form to the apostolic creed. The added places are familiar to everyone even today. God became the "creator of heaven and

From the book Selected Works on the Spirit of Laws author Montesquieu Charles LouisCHAPTER XVI On the attitude of the legislator to the reproduction of the clan The nature of the regulations regulating the number of citizens largely depends on the circumstances. There are countries where nature has done everything for this purpose, leaving nothing to the legislator. No need to encourage

From the book Everyday Life of a Russian Provincial Town in the 19th Century. Post-reform period author Mitrofanov Alexey Gennadievich From the book The Secret of Holy Rus' [History of the Old Believers in events and persons] author Urushev Dmitry AlexandrovichCHAPTER VI JOB FROM THE CLASS OF THE RECKER Among the ascetics revered by the Old Believer Church, a special place belongs to Job of Lgov. He testified his fidelity to “ancient piety” not by confessional feat and martyrdom, but by monastic humility and

From the book History of Armenia author Khorenatsi Movses84 Extermination of the Slkuni clan by Mamgon from the Chen clan When the Persian king Shapukh took a break from wars, and Trdat went to Rome to visit Saint Constantine, Shapukh, freed from thoughts and worries, began to plot evil against our country. Having encouraged all the northerners to attack Armenia, he

From the book of Genghis Khan author Sklyarenko Valentina MarkovnaThe young head of the Rodnoy Ulus clan met Temujin unfriendly. The Taichiuts who were part of it, who had previously been jealous of Yesugei’s power, now decided that their time had come. They abandoned Hoelun and another of Baatur's wives in the middle of the steppe with a handful of female servants and

From Yusupov's book. Incredible story by Blake SarahChapter 22 Houses of the Yusupovs But where are the treasures of the Yusupov family now? Almost everything remained in Russia: lands, palaces, collections of paintings, all property. Very little was taken away. Several years ago, Ksenia Nikolaevna was forced to sell a painting in London for next to nothing

From the book The Last Rurikovichs and the Decline of Muscovite Rus' author Zarezin Maxim IgorevichChapter 10 AN ORPHANT FROM THE KIND OF AUGUSTUS An abomination for kings is a lawless deed, because the throne is established by righteousness. The king delights in truthful lips, and he loves the one who speaks the truth. The king's wrath is the harbinger of death, but a wise man will appease it. Book of Proverbs

From the book of the Stroganovs. The richest in Russia by Blake SarahChapter 15 The last of the Stroganov family The grandniece of Sergei Grigorievich, Elena Andreevna Stroganova (Baroness Helene de Ludinghausen), now lives in France. A unique woman, she combines Stroganov’s extraordinary passion for art and beauty

From the book Marina Mnishek [The incredible story of an adventurer and a warlock] author Polonska JadwigaChapter 16. The curse of the Romanov family Marianna was happy. Nearby was Ivan Zarutsky, whom Dmitry disliked so much. And she often thought that her first husband, looking from heaven at her and Zarutsky, regretted that he was going to execute the Cossack chieftain.

From the book Gordian Knot of the Russian Empire. Power, gentry and people in Right Bank Ukraine (1793-1914) by Beauvois DanielChapter 2 WHAT TO DEAL WITH THIS KIND OF PEOPLE?

author Sidorov Georgy AlekseevichChapter 17. Cult of the Family Now let's get acquainted with the Russian Vedic gods. Actually, we have already met the progenitor of the heavenly Orian gods, we are talking about the great Family. It was his consciousness and will that turned on the process of formation of the supramaterial informational

From the book Secret Chronology and Psychophysics of the Russian People author Sidorov Georgy AlekseevichChapter 32. Commandments of the Family The entire Judeo-Christian world knows the famous commandments of the prophet Moses. These commandments were also automatically accepted by Christians, and there were very few people who doubted their divinity. What these commandments are for

The Yusupov family was one of the most famous noble dynasties of Tsarist Russia. This family included military men, officials, administrators, senators, collectors and philanthropists. The biography of each Yusupov is a fascinating story about the life of an aristocrat against the backdrop of his era.

Origin

The founder of the Yusupov princely family was considered the Nogai Khan Yusuf-Murza. In 1565 he sent his sons to Moscow. As major military leaders and Tatar nobles, the descendants of Yusuf received the Volga city of Romanov, not far from Yaroslavl, as their feeding. Under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich they were baptized. Thus, the origin of the Yusupov family can be dated back to the 16th-17th centuries.

Grigory Dmitrievich

In the history of this aristocratic family, it is noteworthy that the Yusupov family tree for several centuries did not acquire many additional lines and branches. A high-ranking family always consisted of a father and his only son, to whom all parental property passed. This state of affairs was unusual for the Russian nobility, among whom a large number of heirs was commonplace.

Yusuf's great-great-grandson Grigory Dmitrievich Yusupov (1676-1730) received the rank of steward granted to him by Tsar Feodor III in infancy. Being the same age as Peter I, he spent his childhood with him, becoming one of the faithful comrades of the autocrat's youth. Gregory served in a dragoon regiment and in its ranks participated in the next Russian-Turkish war. The culmination of that campaign was the Azov campaigns, in which Peter wanted to gain access to the southern seas. After the victory over the Turks, Yusupov solemnly entered Moscow in the royal retinue.

Closer to Peter I

Soon the Northern War began. The history of the Yusupov family is the history of aristocrats who faithfully repaid their debt to the country from generation to generation. Grigory Dmitrievich set an example for his descendants in his service. He took part in the battle of Narva and the battle of Lesnaya, where he was wounded twice. In 1707, the military man received the rank of major in the Preobrazhensky Regiment.

Despite his injuries, Yusupov was with the troops during the Battle of Poltava and during the capture of Vyborg. He also took part in the unsuccessful Prut campaign. Georgy Dmitrievich was brought to work on the case of Tsarevich Alexei, who fled from his father abroad and was then put on trial. Yusupov, along with other close associates of the monarch, signed the verdict.

Under Catherine I, the aristocrat received the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky and became a commander in the Ukrainian Landmilitary Corps. Peter II made him one of the members of the Military Collegium, and Anna Ioannovna made him general-in-chief. Grigory Dmitrievich died in 1730. He was buried in the Moscow Epiphany Monastery.

Boris Grigorievich

The further history of the Yusupov family continued with the vivid biography of Grigory Dmitrievich’s son, Boris Grigorievich Yusupov (1695-1759). Peter I sent him, along with several other noble young men, to study at the French military school in Toulon. In 1730 he became chamberlain, and at the age of 40 he entered the Senate.

Under Boris Grigorievich, the noble family of the Yusupovs achieved paramount importance. For two years (1738-1740), the head of the family was the Moscow vice-governor and manager of the provincial chancellery. The official initiated local reforms, the draft of which was adopted by the Senate. In particular, Yusupov advocated conducting a census of suburban and streltsy lands, as well as the creation of the post of Moscow commandant.

In 1740, Boris Grigorievich received the rank of Privy Councilor. Then he was briefly appointed Moscow governor. The official was removed from office already in 1741, when Elizaveta Petrovna came to power. The history of the Yusupov family knew many important appointments. Having resigned his gubernatorial powers, Boris Grigorievich received a new space for activity - the Empress made him president of the Commerce Collegium, which was responsible for the state of domestic trade. He was also appointed director of the Ladoga Canal.

In 1749, the nobleman served as Governor-General of St. Petersburg. He soon left this post, moving to the government Senate and beginning to manage the Land Noble Corps. Under him, deductions for the maintenance of cadets increased, and an educational printing house appeared. In 1754, Boris Grigorievich acquired a cloth factory in the Chernigov village of Ryashki. This enterprise began to supply almost the entire Russian army with fabrics. The factory used Dutch raw materials and employed foreign specialists. In 1759, Boris Grigorievich became seriously ill, resigned and died a few days later. The story of the Yusupov family, however, did not end.

Nikolay Borisovich

The continuation of the dynasty was the son of Boris Grigorievich, Nikolai Borisovich (1750-1831). He became one of the main art collectors of his era. Boris Grigorievich received a high-quality education abroad. In 1774-1777 he studied at Leiden University. There, the young man developed an interest in European art and culture. He managed to visit almost all countries of the Old World and communicate with the great enlighteners Voltaire and Diderot. The princely family of the Yusupovs was always proud of these acquaintances of their ancestor.

In Leiden, the aristocrat began collecting rare editions of books, in particular the works of Cicero. The German artist Jacob Hackert became his advisor on painting issues. Some paintings by this master turned out to be the first exhibits in the collection of the Russian prince. In 1781-1782 he accompanied the heir to the throne, Pavel Petrovich, on a European tour.

Subsequently, Yusupov became the main link between the authorities and foreign artists. Thanks to his connection with the imperial family, the nobleman was able to establish contacts with the main artists of that time: Angelika Kaufman, Pompeo Batoni, Claude Vernet, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Jean-Antoine Houdon, etc.

At the coronation of Paul I, which took place in 1796, Yusupov served as the supreme coronation marshal (he then acted in the same capacity at the coronations of the next two autocrats: Alexander I and Nicholas I). The prince was the director of the Imperial theaters, the Hermitage and palace factories for the production of glass and porcelain. In 1794 he was elected as an honorary amateur of the Academy of Arts of St. Petersburg. Under Yusupov, the Hermitage for the first time carried out an inventory of the entire wide collection of exhibits. These lists were used throughout the 19th century.

In 1810, the prince bought Arkhangelskoye, an estate near Moscow, which he turned into a unique palace and park ensemble. By the end of his life, the nobleman’s collection included more than 600 valuable paintings, thousands of unique books, as well as works of applied art, sculptures, and porcelain. All these unique exhibits were placed in Arkhangelsk.

Numerous high-ranking guests visited Yusupov’s Moscow house on Bolshoi Kharitonyevsky Lane. For some time, the Pushkins lived in this palace (including the still child Alexander Pushkin). Shortly before his death, Nikolai Borisovich attended a festive dinner at the apartment of a newly married poet and writer. The prince died in 1831 during a cholera epidemic that swept through the central provinces of the country.

Boris Nikolaevich

Nikolai Borisovich's heir, Boris Nikolaevich (1794-1849), continued the Yusupov family. The 19th century became for the princely family a continuation of its brilliant aristocratic history. Young Boris went to get an education at the capital's pedagogical institute. In 1815 he began working in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Soon he was made chamberlain.

Like all young aristocrats, he conducted the traditional familiarization tour of Europe, which took a full year and a half. In 1826, he participated in the coronation of Nicholas I. At the same time, he went to work at the Ministry of Finance. Service in the previous diplomatic department did not work out, since Boris Nikolaevich constantly conflicted with colleagues, allowed himself to behave freely with his superiors, etc. As a representative of an influential and wealthy family, he did not cling to the service and always adhered to an independent line of behavior.

In 1839, Yusupov became the district leader of the St. Petersburg nobility. Soon he received the court title of chamberlain. In his youth, the prince was distinguished by his lifestyle as a reveler. After the death of his father, he received a gigantic inheritance and over time learned to handle money prudently. At the same time, Boris Nikolaevich allowed himself to do things unusual for a business executive. In particular, all his serfs were freed.

In high society, Boris Yusupov was best known as the organizer of luxurious balls, which became the main social events of the capital. The prince himself was a moneylender and, through financial transactions involving the purchase of enterprises, increased his family fortune several times. The nobleman had estates in 17 provinces of the country. During epidemics, he was not afraid to inspect his own estates, and during seasons of famine, he fed the gigantic servants at his own expense. The aristocrat donated significant sums to public charity institutions. He died in 1849 at the age of 55.

Nikolai Borisovich (junior)

The deceased prince had an only son, Nikolai Borisovich (1827-1891). Relatives, so as not to confuse him with his grandfather, called him “junior”. The newborn was baptized by Tsar Nicholas I himself. The boy was taught music (piano and violin), as well as drawing, to which he became extremely addicted from a very early age. The Paris Conservatory and the Philharmonic Academy of Bologna made the prince an honorary member.

In 1849, the young man inherited his father's fortune. A few months later he graduated from St. Petersburg University, where he studied at the Faculty of Law. Having received his education, the college secretary began working in the imperial office. In 1852 he was transferred to the Caucasus and then to Riga. The reason for the rotation was the displeasure of Emperor Nicholas I. In Riga, Yusupov received leave and went on a European trip. There he took up music, visited artists' workshops and the best art galleries.

In 1856, the prince attended the coronation of Alexander I. Then he served for a short time in the Russian embassy in Paris. The aristocrat spent most of his time abroad. His family fortune allowed him not to worry about service, but simply to do what he loved.

Nikolai Borisovich continued to expand the Yusupov collection of works of art. He owned rare snuff boxes, rock crystal, pearls and other valuables. The prince always had a wallet with him filled with rare stones. His collection also included musical instruments: grand pianos, harps, upright pianos, organs, etc. The crowning glory of the collection were Stradivarius violins. Some of Yusupov's music collections are now kept in the Russian National Library. In 1858, a nobleman brought one of the first cameras to his homeland. Like his father, he was involved in charity work. During the Crimean campaign, Nikolai Borisovich financed the organization of two infantry battalions, and during the next war with Turkey he gave money for the creation of a sanitary train. Yusupov died in Baden-Baden in 1891 at the age of 63.

Zinaida Nikolaevna

Nikolai Borisovich had an only daughter - Zinaida Yusupova (1861-1939). Having no male heirs, the prince asked permission for the princely dignity to be passed on to his grandchildren through the female line, although this was contrary to custom. In 1882 the girl got married. Her chosen one was Count Felix Sumarokov-Elston, which is why Zinaida became known as Princess Yusupova, Countess Sumarokov-Elston.

The only heir to a huge fortune and a woman of rare beauty, the daughter of Nikolai Borisovich was the most enviable bride in Russia before her marriage. Not only Russian aristocrats, but even representatives of foreign monarchical families sought her hand.

The last of the Yusupov family lived in grand style. She organized regular high-profile balls. The life of the capital's elite was in full swing in its palaces. The woman danced beautifully. In 1903, she took part in a costume ball held in the Winter Palace and which became one of the most famous events of this kind in the history of Imperial Russia.

The husband, whom Zinaida Yusupova loved very much, was a military man and was not interested in art. Partly because of this, the woman sacrificed her hobbies. Nevertheless, she was involved in charity work with renewed energy. The aristocrat patronized and maintained gymnasiums, hospitals, orphanages, churches and other institutions. They were located not only in the capital, but throughout the country. After the start of the war with Japan, Zinaida Nikolaevna became the chief of the front-line sanitary echelon. Hospitals for the wounded were created on Yusupov's estates. No other women of the Yusupov family were as active and famous as Zinaida Nikolaevna.

After the revolution, the princess moved to Crimea, and from there abroad. Together with her husband she settled in Rome. Unlike many other nobles, the Yusupovs were able to send part of their fortune and jewelry abroad, thanks to which they lived in abundance. Zinaida Nikolaevna continued to do charity work. She helped Russian emigrants in need. After the death of her husband, the woman moved to Paris. There she died in 1939.

Felix Feliksovich

The last of the Yusupov princes was Zinaida's son Felix Feliksovich Yusupov (1887-1967). As a child, he was educated at the Gurevich gymnasium and was a prominent figure of the golden youth of St. Petersburg in the last years of Tsarist Russia. At the age of 25 he graduated from Oxford University. At home, he became the head of the First Russian Automobile Club.

In 1914, Felix Feliksovich Yusupov married Irina Alexandrovna Romanova, the maternal niece of Nicholas II. The emperor himself gave permission for the marriage. During their honeymoon, the newlyweds learned about the outbreak of the First World War. The Yusupovs were in Germany, and Wilhelm II even ordered their arrest. Diplomats were brought in to resolve the sensitive situation. As a result, Felix and his wife managed to leave Germany shortly before Wilhelm issued a second order for their detention.

As the only son in the family, the prince was not subject to conscription into the army. Returning home, he began organizing the work of hospitals. In 1915, Felix had a daughter, Irina, from whom the modern descendants of the Yusupov family descend.

The aristocrat is best known for his own participation in the murder of Grigory Rasputin in December 1916. Felix was very close to the imperial family. He knew Rasputin and, like many, believed that the strange old man was a bad influence on Nicholas II and his prestige. The prince dealt with the royal friend along with his brother-in-law, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, and State Duma deputy Vladimir Purishkevich. The Emperor, having learned about the death of Rasputin, ordered Yusupov to move away from the capital to his own Kursk estate Rakitnoye.

There was no further accountability for the murder. Soon the revolution broke out, and Felix Feliksovich emigrated. The prince settled in Paris and lived from the sale of family treasures. During World War II, he did not support the Nazis, and after their defeat he refused to return to Russia, as many emigrants did (all of them were eventually repressed in their homeland). Prince Felix Yusupov died in 1967. His surname was dropped, although descendants from his daughter Irina continue to live abroad.

Possessions

As one of the richest families in Russia, the Yusupovs had many residences and properties in different parts of the country. A significant part of these buildings are today protected by the state as monuments of architectural and cultural heritage. The St. Petersburg Yusupov Palace, located on the banks of the Moika River, still bears their name, which has become a household name for the townspeople. It was built back in 1770.

The second Yusupov Palace (also in St. Petersburg) is located on Sadovaya Street. Built at the end of the 18th century, today it is the property of the University of Railways. Being an estate, this residence was one of the most spectacular and rich in the capital. The palace project belonged to the famous Italian architect Giacomo Quarenghi.

The Arkhangelskoye estate, which became the storage place for Yusupov's collection of antiques and works of art, was the favorite princely home outside St. Petersburg. The palace and park complex is located in the Krasnogorsk district of the Moscow region. Shortly before the revolution, the Yusupovs built their own Miskhor Palace in Crimea. In the Belgorod region, the main house of the princely estate of Rakitnoye, around which a whole village has grown, is still preserved. Today it houses a local history museum.

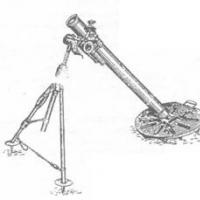

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force

US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force Differentiation of functions

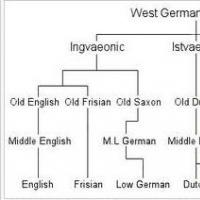

Differentiation of functions Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages

Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages Which scientist introduced the concept of valency?

Which scientist introduced the concept of valency? How does a comet grow a tail?

How does a comet grow a tail?