Extracurricular event "In the old days, children studied...". The first schools in Rus' How they studied in the schools of ancient Rus' message

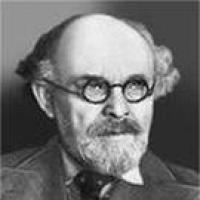

Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev (1830-1905)

Metal inkwells typical of Russia from the 17th century. Throughout the Middle Ages, their shape remained unchanged.

Fresco from Pompeii. 1st century AD e. Portrait of a townsman with a scroll in his hand and his wife, who is holding cerae (Day Roman writing tablets) and a style - a sharp writing stick.

An ancient Roman relief depicts a home teaching scene: on either side of the teacher are boys busy reading papyri.

In 1901, Boris Kustodiev painted a portrait of D. L. Mordovtsev.

A page from Karien Istomin's primer, printed in the printing house of the Moscow Printing House in 1694.

A miniature from a 17th-century handwritten book telling about schooling in Rus'.

The temptation to “look” into the past and “see” a bygone life with one’s own eyes overwhelms any historian-researcher. Moreover, such time travel does not require fantastic devices. An ancient document is the most reliable carrier of information, which, like a magic key, unlocks the treasured door to the past. This blessed opportunity for a historian was given to Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev, a famous journalist and writer in the 19th century. His historical monograph “Russian School Books” was published in 1861 in the fourth book of “Readings in the Society of Russian History and Antiquities at Moscow University.” The work is dedicated to the ancient Russian school, about which at that time (and indeed even now) so little was known.

... And before this, there were schools in the Russian kingdom, in Moscow, in Veliky Novograd and in other cities... They taught literacy, writing and singing, and honor. That’s why there were many people who were very good at reading and writing, and scribes and readers were famous throughout the land.

From the book "Stoglav"

Many people are still confident that in the pre-Petrine era in Rus' nothing was taught at all. Moreover, education itself was then allegedly persecuted by the church, which only demanded that students somehow recite prayers by heart and little by little sort out printed liturgical books. Yes, and they taught, they say, only the children of the priests, preparing them for taking orders. Those of the nobility who believed in the truth “teaching is light...” entrusted the education of their offspring to foreigners discharged from abroad. The rest were found “in the darkness of ignorance.”

Mordovtsev refutes all this. In his research, he relied on an interesting historical source that fell into his hands - “Azbukovnik”. In the preface to the monograph dedicated to this manuscript, the author wrote the following: “Currently, I have the opportunity to use the most precious monuments of the 17th century, which have not yet been published or mentioned anywhere and which can serve to explain the interesting aspects of ancient Russian pedagogy. Materials these are contained in a lengthy manuscript bearing the name “Azbukovnik” and containing several different textbooks of that time, written by some “pioneer”, partly copied from other, similar publications, which were entitled with the same name, although they differed in content and had different counts of sheets."

Having examined the manuscript, Mordovtsev makes the first and most important conclusion: in Ancient Rus', schools as such existed. However, this is also confirmed by an older document - the book “Stoglav” (a collection of resolutions of the Stoglav Council, held with the participation of Ivan IV and representatives of the Boyar Duma in 1550-1551). It contains sections that talk about education. In them, in particular, it is determined that schools are allowed to be maintained by persons of clergy rank, if the applicant receives permission from the church authorities. Before issuing one to him, it was necessary to test the thoroughness of the applicant’s own knowledge, and collect possible information about his behavior from reliable guarantors.

But how were the schools organized, how were they managed, and who studied in them? “Stoglav” did not give answers to these questions. And now several handwritten “Azbukovniks” - very interesting books - fall into the hands of a historian. Despite their name, these are, in fact, not textbooks (they contain neither the alphabet, nor copybooks, nor teaching numeracy), but rather a guide for the teacher and detailed instructions for students. It spells out the student’s complete daily routine, which, by the way, concerns not only school, but also the behavior of children outside of it.

Following the author, we too will look into the Russian school of the 17th century; fortunately, “Azbukovnik” gives full opportunity to do so. It all starts with the arrival of children in the morning to a special home - a school. In various ABC books, instructions on this matter are written in verse or prose; they, apparently, also served to strengthen reading skills, and therefore the students persistently repeated:

In your house, having risen from sleep, washed yourself,

Wipe the edge of the board well,

Continue in the veneration of holy images,

Bow low to your father and mother.

Go to school carefully

And lead your comrade,

Enter school with prayer,

Just go out there.

The prose version also teaches about the same thing.

From "Azbukovnik" we learn a very important fact: education in the times described was not a class privilege in Rus'. In the manuscript, on behalf of “Wisdom,” there is an appeal to parents of different classes to send their children to be taught “extreme literature”: “For this reason I speak continually and will never cease in the hearing of pious people, of every rank and dignity, glorious and honorable, rich and wretched, even to the last farmers." The only limitation to education was the reluctance of the parents or their sheer poverty, which did not allow them to pay the teacher anything for educating their child.

But let us follow the student who entered the school and had already placed his hat on the “common bed,” that is, on the shelf, bowed to the images, and to the teacher, and to the entire student “squad.” A student who came to school early in the morning had to spend the whole day there until the bell rang for the evening service, which was the signal for the end of classes.

The teaching began with the answer to the lesson studied the day before. When the lesson was told by everyone, the whole “squad” performed a common prayer before further classes: “Lord Jesus Christ our God, creator of every creature, give me understanding and teach me the scriptures of the book, and hereby I will obey Your desires, for I will glorify You forever and ever, Amen !"

Then the students approached the headman, who gave them the books they were to study from, and sat down at a common long student table. Each one took the place assigned to him by the teacher, observing the following instructions:

The malia in you and the greatness are all equal,

For the sake of the teachings, let them be noble...

Do not disturb your neighbor

And don’t call your friend by his nickname...

Don't be close to each other,

Do not use your knees and elbows...

Some place given to you by the teacher,

Let your life be included here...

Books, being the property of the school, constituted its main value. The attitude towards the book was reverent and respectful. It was required that the students, having “closed the book,” always put it with the seal facing up and did not leave “indicative trees” (pointers) in it, did not unbend it too much and did not leaf through it in vain. It was strictly forbidden to place books on the bench, and at the end of the lesson, the books had to be given to the headman, who put them in the designated place. And one more piece of advice - do not get carried away by looking at book decorations - “tumbles”, but strive to understand what is written in them.

Keep your books well

And put it in a dangerous place.

...The book, closed, sealed to height

I guess

There is no index tree in it at all

don't invest...

Books to the elder for observance,

with prayer, bring,

Taking the same thing in the morning,

with respect, please...

Don’t unbend your books,

And don’t bend the sheets in them either...

Books on the seat

Do not leave,

But on the prepared table

please supply...

Who doesn’t take care of books?

Such a person does not protect his soul...

The almost verbatim coincidence of phrases in the prose and poetic versions of different “Azbukovniki” allowed Mordovtsev to assume that the rules reflected in them were the same for all schools of the 17th century, and therefore, we can talk about their general structure in pre-Petrine Rus'. The same assumption is prompted by the similarity of the instructions regarding the rather strange requirement that prohibits students from talking outside the school walls about what is happening in it.

Leaving home, school life

don't tell me

Punish this and every one of your comrades...

Ridiculous words and imitation

don't bring it to school

Do not wear out the deeds of those who were in it.

This rule seemed to isolate the students, closing the school world into a separate, almost family community. On the one hand, it protected the student from the “unhelpful” influences of the external environment, on the other hand, it connected the teacher and his students with special relationships inaccessible even to close relatives, and excluded the interference of outsiders in the process of teaching and upbringing. Therefore, to hear from the lips of the then teacher the now so often used phrase “Don’t come to school without your parents” was simply unthinkable.

Another instruction, similar to all “Azbukovniki,” speaks of the responsibilities that were assigned to students at school. They had to “add up the school”: sweep away the rubbish, wash the floors, benches and tables, change the water in the vessels under the “light” - a stand for a torch. Lighting the school with the same torch was also the responsibility of the students, as was firing the stoves. The head of the school “team” assigned students to such work (in modern language, on duty) in shifts: “Whoever heats the school, installs everything in that school.”

Bring fresh water vessels to school,

Take out the tub of stagnant water,

The table and benches are washed cleanly,

Yes, it is not disgusting for those who come to school;

This way your personal beauty will be known

You will also have school cleanliness.

The instructions urge students not to fight, not to play pranks, and not to steal. It is especially strictly prohibited to make noise in and around the school itself. The rigidity of this rule is understandable: the school was located in a house owned by the teacher, next to the estates of other residents of the city. Therefore, noise and various “disorders” that could arouse the anger of neighbors could well turn into a denunciation to the church authorities. The teacher would have to give the most unpleasant explanations, and if this is not the first denunciation, then the owner of the school could “be subject to a ban on maintaining the school.” That is why even attempts to break school rules were stopped immediately and mercilessly.

In general, discipline in the ancient Russian school was strong and severe. The whole day was clearly outlined by rules, even drinking water was allowed only three times a day, and “going to the yard for the sake of need” was only possible with the permission of the headman only a few times. This paragraph also contains some hygiene rules:

For the sake of need, who needs to go,

Go to the headman four times a day,

Come back from there immediately,

Wash your hands to keep them clean,

Whenever you go there.

All "Azbukovnik" had an extensive section - about the punishment of lazy, careless and obstinate students with a description of the most diverse forms and methods of influence. It is no coincidence that “Azbukovniki” begins with a panegyric to the rod, written in cinnabar on the first page:

God bless these forests,

The same rods will give birth for a long time...

And it’s not just “Azbukovnik” that praises the rod. In the alphabet, printed in 1679, there are these words: “The rod sharpens the mind, awakens the memory.”

However, one should not think that he used the power that the teacher possessed beyond all measure - good teaching cannot be replaced by skillful flogging. Nobody would teach someone who became famous as a tormentor and a bad teacher. Innate cruelty (if any) does not suddenly appear in a person, and no one would allow a pathologically cruel person to open a school. How children should be taught was also discussed in the Code of the Stoglavy Council, which was, in fact, a guide for teachers: “not with rage, not with cruelty, not with anger, but with joyful fear and loving custom, and sweet teaching, and gentle consolation.”

It was between these two poles that the path of education lay somewhere, and when the “sweet teaching” was of no use, then a “pedagogical instrument” came into play, according to experts, “a sharpening mind, stimulating the memory.” In various "Azbukovniks" the rules on this matter are set out in a way that is understandable to the most "rude-minded" student:

If anyone becomes lazy with teaching,

Such a wound will not be ashamed...

Flogging did not exhaust the arsenal of punishments, and it must be said that the rod was the last in that series. The naughty boy could be sent to a punishment cell, the role of which was successfully played by the school “necessary closet”. There is also a mention in “Azbukovniki” of such a measure, which is now called “leave after school”:

If someone doesn't teach a lesson,

One from free school

won't receive...

However, there is no exact indication whether the students went home for lunch in “Azbukovniki”. Moreover, in one of the places it is said that the teacher “during the time of bread-eating and midday rest from teaching” should read to his students “useful writings” about wisdom, about encouragement for learning and discipline, about holidays, etc. It remains to be assumed that Schoolchildren listened to this kind of teaching during a common lunch at school. And other signs indicate that the school had a common dining table, maintained by the parents' contributions. (However, perhaps this particular order was not the same in different schools.)

So, the students were constantly at school for most of the day. In order to have the opportunity to rest or be absent on necessary matters, the teacher chose an assistant from among his students, called the headman. The role of the headman in the internal life of the then school was extremely important. After the teacher, the headman was the second person in the school; he was even allowed to replace the teacher himself. Therefore, the choice of a headman for both the student “squad” and the teacher was the most important matter. "Azbukovnik" prescribed that the teacher himself should select such students from among the older students who were diligent in their studies and had favorable spiritual qualities. The book instructed the teacher: “Keep on your guard against them (that is, the elders. - V.Ya.). The kindest and most skillful students who can announce them (the students) even without you. V.Ya.) a shepherd's word."

The number of elders is spoken of differently. Most likely, there were three of them: one headman and two of his assistants, since the circle of responsibilities of the “chosen ones” was unusually wide. They monitored the progress of school in the absence of the teacher and even had the right to punish those responsible for violating the order established in the school. They listened to the lessons of younger schoolchildren, collected and gave out books, monitored their safety and proper handling. They were in charge of "leave to the yard" and drinking water. Finally, they managed the heating, lighting and cleaning of the school. The headman and his assistants represented the teacher in his absence, and in his presence - his trusted assistants.

The headmen carried out all the management of the school without any reporting to the teacher. At least, that’s what Mordovtsev thought, not finding a single line in “Azbukovniki” that encouraged fiscalism and gossip. On the contrary, students were taught in every possible way to comradeship, to life in a “squad”. If the teacher, looking for the offender, could not accurately point to a specific student, and the “squad” did not give him away, then the punishment was announced to all students, and they chanted in chorus:

Some of us have guilt

Which was not before many days,

The culprits, hearing this, blush their faces,

They are still proud of us, the humble ones.

Often the culprit, in order not to let down the “squad,” removed the ports and himself “climbed onto the goat,” that is, he lay down on the bench, on which the “assignment of lozans to fillet parts” was carried out.

Needless to say, both the teaching and the upbringing of the youths were then imbued with deep respect for the Orthodox faith. What is invested from a young age will grow in an adult: “This is your childhood, the work of students in school, especially those who are perfect in age.” Students were required to go to church not only on holidays and Sundays, but also on weekdays, after finishing school.

The evening bell signaled the end of the teaching. “Azbukovnik” teaches: “When you are released, you all rise up in droves and give your books to the bookkeeper, with a single proclamation everyone, collectively and unanimously, chant the prayer of St. Simeon the God-Receiver: “Now do you let go of Your servant, Master” and “Glorious Ever-Virgin.” After this, the disciples were to to go to vespers, the teacher instructed them to behave decently in church, because “everyone knows that you are studying at school.”

However, demands for decent behavior were not limited to school or temple. The school rules also extended to the street: “When the teacher dismisses you at such a time, go home with all humility: jokes and blasphemies, kicking each other, and beating, and running around, and throwing stones, and all sorts of similar childish mockery, let it not dwell in you." Aimless wandering through the streets was also not encouraged, especially near all sorts of “entertainment establishments,” then called “disgraces.”

Of course, the above rules are better wishes. There are no children in nature who would refrain from “spitting and running around”, from “throwing stones” and going to “disgrace” after they spent the whole day at school. In the old days, teachers also understood this and therefore sought by all means to reduce the time students spend unsupervised on the street, which pushes them into temptations and pranks. Not only on weekdays, but on Sundays and holidays, schoolchildren were required to come to school. True, on holidays they no longer studied, but only answered what they had learned the day before, read the Gospel aloud, listened to the teachings and explanations of their teacher about the essence of the holiday of that day. Then everyone went to church together for the liturgy.

The attitude towards those students whose studies were going poorly is curious. In this case, “Azbukovnik” does not at all advise them to flog them intensively or punish them in any other way, but, on the contrary, instructs: “whoever is a “greyhound learner” should not rise above his fellow “rough learner.” The latter were strongly advised to pray, calling on God for help. And the teacher worked with such students separately, constantly telling them about the benefits of prayer and giving examples “from scripture,” talking about such ascetics of piety as Sergius of Radonezh and Alexander of Svir, to whom teaching was not at all easy at first.

From "Azbukovnik" one can see the details of a teacher's life, the subtleties of relationships with students' parents, who paid the teacher, by agreement and if possible, payment for the education of their children - partly in kind, partly in money.

In addition to school rules and procedures, "Azbukovnik" talks about how, after completing primary education, students begin to study the "seven free arts." By which were meant: grammar, dialectics, rhetoric, music (meaning church singing), arithmetic and geometry (“geometry” was then called “all land surveying,” which included geography and cosmogony), and finally, “the last one, but The first action" in the list of sciences studied then was called astronomy (or in Slavic "star science").

And in the schools they studied the art of poetry, syllogisms, studied celebras, the knowledge of which was considered necessary for “virtuous diction”, became acquainted with “rhyme” from the works of Simeon of Polotsk, learned poetic measures - “one and ten kinds of verse.” We learned to compose couplets and maxims, write greetings in poetry and prose.

Unfortunately, the work of Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev remained unfinished, his monograph was completed with the phrase: “The Reverend Athanasius was recently transferred to the Astrakhan Diocese, depriving me of the opportunity to finally parse the interesting manuscript, and therefore, not having the ABC Books at hand, I was forced to finish my "The article is where it left off. Saratov 1856."

And yet, just a year after Mordovtsev’s work was published in the journal, his monograph with the same title was published by Moscow University. The talent of Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev and the multiplicity of topics touched upon in the sources that served to write the monograph, today allow us, with minimal “speculation of that life,” to make a fascinating and not without benefit journey “against the flow of time” into the seventeenth century.

V. YARKHO, historian.Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev (1830-1905), having graduated from a gymnasium in Saratov, studied first at Kazan University, then at St. Petersburg University, from which he graduated in 1854 from the Faculty of History and Philology. In Saratov he began his literary activity. He published several historical monographs, published in “Russian Word”, “Russian Bulletin”, “Bulletin of Europe”. The monographs attracted attention, and Mordovtsev was even offered to occupy the department of history at St. Petersburg University. Daniil Lukich was no less famous as a writer on historical topics.

From Bishop Afanasy Drozdov of Saratov, he receives handwritten notebooks from the 17th century telling about how schools were organized in Rus'.

This is how Mordovtsev describes the manuscript that came to him: “The collection consisted of several sections. The first contains several ABC books, with a special count of notebooks; the second half consists of two sections: in the first - 26 notebooks, or 208 sheets; in the second, 171 sheets The second half of the manuscript, both of its sections, were written by the same hand... The entire section, consisting of “Azbukovniks”, “Pismovnikov”, “School deaneries” and others - up to page 208, was written in the same hand. in handwriting, but with different ink it is written up to the 171st sheet and on that sheet, in a “four-pointed” cunning secret script, it is written “Started in the Solovetsky Hermitage, also in Kostroma, near Moscow in the Ipatskaya monastery, by the same first wanderer in the year of world existence 7191 (1683 .)".

What was taught in Ancient Rus'?

As we have already found out, the first school in Rus' opened in 988 on the initiative of Prince Vladimir. Since Rus' received baptism from Byzantium, the first monastic teachers were invited from there. Now we can definitely say that it was Vladimir who laid the foundations for the development of the school education system in Ancient Rus'. This is evidenced by the fact that, sending their children to school, mothers cried over them as if they were dead. Even in high society they did not yet know what schooling was, and, as we remember, children in the first schools were recruited from noble and boyar families. However, Byzantine influence contributed to the rapid flourishing of school affairs in Kyiv, Novgorod and the centers of other ancient Russian principalities; it gave impetus to the emergence and development of Russian religious and pedagogical thought.

300 boys studied at Prince Vladimir's school "Book Teaching". The teachers were invited Byzantine monks. Alexey Tikhomirov believes that only one subject was taught at this school, namely bookmaking, i.e. children were taught to read. He also points to other sciences studied at school, but the historian does not say which sciences they were. He also does not provide any information about curricula for the study of individual subjects. Probably, according to A. Tikhomirov, the monastic teachers themselves determined what to teach and how to teach.

The Polish historian Jan Dlugosz (1415-1480) reports about the Kyiv school of “book learning” “Vladimir... attracts Russian youths to study the arts, in addition, he maintains masters requested from Greece.” To create a three-volume history of Poland, Dlugosz used Polish, Czech, Hungarian, German sources, and ancient Russian chronicles. Apparently, from a chronicle that has not reached us, he learned the news about studying arts at the Kyiv Vladimir School. Thus, we learn that invited masters also taught in the first schools. They were probably master craftsmen who knew their craft well. It is not reported what particular arts were taught at Vladimir’s school.

It seems unlikely to us that there was teaching in a palace school, where the children of nobles and boyars studied, i.e. upper class, master craftsmen. There were plenty of similar masters in Rus'. Since ancient times, Russian traders exported to Byzantium and other countries not only the products of crafts, but also the products of Russian artisans. In ancient Russian cities, master craftsmen took the children of townspeople for training, but there were no boyar or noble children among them. Perhaps we are talking about the art of icon painting, which Russian masters did not master before the adoption of Christianity. But, as is known, monks were also engaged in icon painting. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that only monks were teachers in Vladimir’s schools.

N. Lavrovsky in his work “On Old Russian Schools” informs us that the disciplines included reading, writing, singing, grammar and arithmetic. N. Lavrovsky does not report any arts. The list of subjects he provided was fully consistent with the social composition of the students and the purpose of organizing the first school in Kyiv. The main goal of this school was to teach literacy to children of the upper population and prepare them for public service, as well as to strengthen and spread Christianity. It is clear that various arts are not needed in the civil service. But singing was necessary, since from the moment of the adoption of Christianity, representatives of the highest circles in Kyiv were systematically present at church services. By analogy with the Byzantine and Western schools of the times of Charlemagne, N. Lavrovsky calls the first schools elementary schools and points out their close connection with the Church. However, such a name in relation to the first school in Kyiv is not found anywhere else. Both in ancient Russian chronicles and in the works of various researchers, the first educational institutions in Kyiv are called schools.

CM. Soloviev points out that schools were organized at churches already in the time of Vladimir, but they were intended to train specifically the clergy of the new Christian church. The children of townspeople, not the children of boyars and nobles, were recruited to study there. The purpose of these schools, organized initially in Kyiv and then in other large cities, was now Christian priests-ascetics of the new faith to spread Christianity to the entire population of Ancient Rus'. This goal determined the set of disciplines and the social composition of students in church schools.

V.O. also speaks about the spread of literacy in Ancient Rus' through such forms of educational institutions as colleges. Klyuchevsky. In addition, he points out that the schools taught Greek and Latin by learned people “who came from Greece and Western Europe.” No more details V.O. Klyuchevsky does not say. However, we further read: “With the help of translated writing, a bookish Russian language was developed, a literary school was formed, original literature developed, and the Russian chronicle of the 12th century is not inferior in skill to the best annals of the then West.” It remains to remember from textbooks on Russian history who wrote the outstanding works of ancient Russian literature, who translated foreign books, especially Greek, and, finally, who was engaged in chronicle writing in Ancient Rus'. These were exclusively monks. Which means S.M. Soloviev was absolutely right. It is obvious that, along with the first school, where boyars and nobles’ children were trained for public service, almost simultaneously the first church schools began to be organized for the training of Christian clergy. We can say with complete confidence that these were completely different educational institutions, despite the fact that the teachers were monks invited from Byzantium in both places. It is likely that foreign languages, Greek and Latin, were taught to children from the upper classes, because public service also involved communicating with foreign guests and working with foreign documents. In this regard, this fact is not surprising.

Academician A.N. Sakharov focuses on the fact that in the first schools, “Vladimir ordered children to be taken from “deliberate”, i.e., rich families.” No details about these A.N. schools. Sakharov does not say. But, developing the idea of the spread and establishment of Christianity in the Russian lands, about its struggle against paganism, he draws the following conclusion: “Schools were created at churches and monasteries, and the first Russian literates were trained in monastery cells. The first Russian artists also worked here, "who, over time, created an excellent school of icon painting. Monks and church leaders were mainly the creators of wonderful chronicle collections, various kinds of secular and church works, instructive conversations, and philosophical treatises." From this it is clear that future priests, called to spread and strengthen the Christian faith, were trained in schools at churches and monasteries. Where does this identification of two educational institutions that are completely different in nature and purpose of teaching come from? We believe that the monks who created the first Russian chronicles had little understanding of the difference between church schools and secular ones. And it was difficult to understand her. The Byzantine character of education was present in both types of educational institutions; the teachers were also Byzantine monks. The first chronicles were created by Russian monastic students of those very first church schools. Of course, they could not understand the complex plan of the authorities who created the first schools. This is where the confusion and identification of secular and church education arose.

Alexey Tikhomirov believes that the term “school” itself appears in Rus' only in 1386, “when, according to pan-European traditions, this term began to designate educational institutions where people were taught crafts and given specialized knowledge.” However, it is a well-known fact that schools, as educational institutions, arose in Ancient Greece and were called “skola”. This information can be read in any textbook on the history of the Ancient World for the 5th grade. Considering that education, like Christianity, came to Rus' from Byzantium, a Greek country, along with the educational institution its name “school” also came. The fact that this term was borrowed from Western European countries raises quite a few doubts.

It is interesting that the place where the first school was organized in Kyiv remains unknown. The year of its foundation - 988 - indicates that churches and monasteries did not yet exist in Rus' at that time. Consequently, it can be assumed that this school for “deliberate” children was organized directly at the court of Prince Vladimir himself, which allowed the latter, without interrupting government affairs, to completely control the education at the school. And a few years later, after the construction of the first Christian church in Kyiv, a church school was organized to train Christian priests. With the construction of new churches, and then monasteries, their number increased significantly.

Many researchers point to the palace character of the first school. In particular, S. Egorov in his History of Pedagogy in Russia writes: “There is reason to assume that the school for “deliberate children”, known from the chronicles, i.e. for the children of the court nobility, close associates of the prince, boyars, and warriors, it was a palace educational institution that trained future state leaders. Its goal was not teaching literacy, known in Rus' long before Prince Vladimir, but training civil servants." Moreover, Egorov S. believes that this school was organized at the temple-residence of the metropolitan and, in addition to boyar children, "many people were educated in it noble foreigners: Hungarians, Norwegians, Swedes, English." It is difficult to say which temple we are talking about in 988. Most likely it was a wooden temple, built at a rapid pace and located next to the residence of Prince Vladimir. And later a stone cathedral was erected, and the school was moved there. As for the education of foreigners in this school, this fact could also well have taken place. In the 10th century, Western Europe did not have a high level of development and it is unlikely that the school education system was developed there during this period of time.

It is important to note that N. Lavrovsky, in his monograph, based on a huge number of chronicle sources, claims that only invited monks taught in Kyiv schools. The author does not focus on this fact, but points out that Vladimir specifically invited learned monks from Byzantium to teach. The author does not mention any other teachers.

It is interesting to note that N. Lavrovsky believes that the training was carried out not at the discretion of the monks, as many researchers believe, but according to a specific plan, which was approved personally by Vladimir. Thus, training programs were developed for each subject. This is not surprising, since the first school had very specific tasks, and the authorities could not let the education process take its course. It is clear that these training plans were developed by the invited monks themselves, following the model of training in Byzantine schools. This conclusion is confirmed by the first Russian taxonomist of the world history of pedagogy L.N. Modzalevsky, also pointing to the Byzantine nature of education in Kievan Rus.

Yaroslav the Wise continued his father's tradition of developing education in Rus'. According to historians, he founded a school at the Kiev Pechersk Monastery, and then in Novgorod, Polotsk and other large cities. The Sophia Chronicle tells us about the founding of a school in Novgorod in 1030: “In the summer of 6538, Yaroslav went to Chyud, and I won, and established the city of Yuryev. And I came to Novugorod, and having collected 300 children from the elders and priests, taught them with a book.” . From here we learn that the children of city elders and priests in the amount of 300 people were gathered for training. The chronicler tells us that Yaroslav fought with the Chud tribes and founded the city of Yuryev in their lands. It must be assumed that in this regard, the school was faced with very specific tasks, namely: the spread of Christianity among pagan tribes and the training of civil service personnel in these places. Yaroslav not only intended to convert the pagans to a new faith, but also to spread the influence of Rus' to these territories in order to expand the borders of the Old Russian state. If we carefully look at the geography of the founding of new schools, we will see that they all opened in border cities. Rus' needed not only educated people, but also competent civil servants, worthy guides to the policies of the Grand Duke. These goals determined the set of subjects studied. The main subjects in church schools were the seven liberal sciences, “free wisdom” (1 - grammar, 2 - rhetoric, 3 - dialectics, 4 - arithmetic, 5 - music, 6 - geometry, 7 - astronomy), and technology. This fully confirms N. Lavrovsky’s information.

As for the structure of the first schools, they were also organized according to the Greek model. Many researchers tell us that all the students were divided into small groups of 5-6 people, each of which was taught by its own monk teacher. The same principle of small groups was used to organize training in schools in Western European countries. Western and domestic sources report that “such a division of students into groups was common in schools in Western Europe at that time. From the surviving acts of the cantor of schools in medieval Paris it is known that the number of students per teacher was from 6 to 12 people, in the schools of the Cluny Monastery - 6 people, in women's primary schools in Til - 4-5 students. Eight students are depicted in the miniature of the front "Life of Sergius of Radonezh", 5 students are seated in front of the teacher in the engraving of the front "ABC" of 1637 by V. Burtsov.

About this number of students is evidenced by the birch bark letters of the famous Novgorod schoolboy of the 13th century. Onfima. One with a handwriting different from Onfim’s (No. 201), hence V.L. Yanin suggested that this letter belonged to Onfim’s school friend. Onfim’s fellow student was Danila, for whom Onfim prepared a greeting: “Bow from Onfim to Danila.” It is possible that a fourth Novgorodian, Matvey (letter certificate No. 108), also studied with Onfim, whose handwriting is very similar." There is no reason to doubt the information provided. Large groups of students with one teacher appeared already in Soviet schools, i.e. after 1917. Before At this time, information about large student classes is nowhere to be found, and it is unlikely that teaching would be effective if the teacher had large classes.

The widespread spread of male education also led to the emergence of the first schools for women. In May 1086, the very first women's school appeared in Rus', the founder of which was Prince Vsevolod Yaroslavovich. Moreover, his daughter, Anna Vsevolodovna, simultaneously headed the school and studied science. Only here could young girls from wealthy families learn to read and write and various crafts. At the beginning of 1096, schools began to open throughout Rus'. It should be noted that Anna Vsevolodovna was essentially the first secular teacher. It is not surprising that women’s literacy evoked deep respect in society. We have already noticed that education was primarily intended for men. But by the beginning of the 11th century, the need and importance of education was recognized by the population quite firmly. Despite the fact that the peasantry still remained outside of education, the rest of society respected educated people, and educated women especially enjoyed this respect. And women who were also involved in teaching children occupied a special position in society. However, such schools were the exception rather than the norm. But nevertheless, the process of education begun by Vladimir took root quite firmly on Russian soil and was continued by his descendants.

Inspired by the topic about the new bill for women with children. The law itself has already been discussed there. But I was surprised how many women want to get out of work as early as possible. That’s exactly what they want, they complain about lack of fulfillment, boredom, and the notorious Groundhog Day. I remember the time of my maternity leave. Well, it wasn't like that. They went out when the child was 1.5 years old, then they did it until they were 3 years old. No one moaned; only those who really needed money came out earlier. Is this a sign of the times? Are there objective reasons? What has changed in this matter, in your opinion? Or am I getting old and it's "the grass was greener back then"

579I believe... you won't let me down...

I read the topic about Kinotavr... there are so many statements about the age of the characters and the inconsistency with their age that I started thinking about what a lady over 40 should look like... so that she is fashionably elegant and according to her age... what are your criteria?

I will educate myself and prepare in advance))

photos are welcome...

Vanilla Cheburashka

Taken from medrussia.org

A resident of Pavlovsky Posad (Moscow region), an active member of the public organization “Parental Resistance”, an anti-vaxxer and the mother of two daughters, was forcibly hospitalized in psychiatric hospital number 15 by court decision. Psychiatrists diagnosed the activist with delusional ideas, but her lawyer believes that the patient was “closed” because of her beliefs, Podmoskovye Segodnya reports.

The daughters of activist Elena study in the middle and junior classes of Lyceum No. 2 named after. V.V. Tikhonov Pavlovsky Posad. In November 2018, a woman had a conflict with the administration of the educational institution: she refused to give her daughter a Mantoux test, allegedly because of an allergy.

“During a routine inspection, Rospotrebnadzor found children without examination for tuberculosis and fined me 30 thousand rubles,” says the director of the lyceum, Marina Serova. “The lyceum’s paramedic suggested that parents take x-rays of their children. Harmful! Refusal! Quantiferon test or t-spot – refusal, expensive! Go to a phthisiatrician for a certificate - refusal!

In this regard, the girls were transferred first to a quarantine class and then to individual training.

This served as a reason for Elena and another anti-vaxxer to sue the lyceum for violation of the right to education and demand to cancel individual education.

The claim was rejected, as were repeated appeals.

According to the director of the lyceum, anti-vaccination mothers rudely burst into the school and called the police. Elena herself once brought a lyceum employee to a hypertensive crisis and wrote complaints to various authorities.

“On April 24, Rospotrebnadzor handed me an order demanding that the brawler’s daughters be suspended from studying at the lyceum within a month due to the fact that one of the students fell ill with tuberculosis in the winter of 2019,” continues Marina Serova. – Parents were asked to choose a distance or family form of education.

Also, the director was twice summoned for a conversation with the Ministry of Education of the Moscow Region in connection with Elena’s complaints, but no violations were identified.

“More than once, the youngest girl came to school with bruises and scratches and said that she had stepped on a rake. The mother forbade the children to eat at the lyceum, because “they would be poisoned there,” and she brought them rye bread for lunch. The girls, at the encouragement of their mother, became embittered and were often left alone,” the director shared.

The children’s clinic, where Elena tore up children’s medical cards, also suffered from the activist’s aggressive behavior.

“As a result, law enforcement agencies ordered an investigation against the woman. Based on its results, the police contacted psychiatric hospital No. 15 about an involuntary psychiatric examination of Elena,” said the activist’s lawyer Rodion Smirnov.

At the end of May 2019, the claim for compulsory examination was satisfied, and on June 4, a court hearing was held on the second claim from psychiatric hospital number 15 - for involuntary hospitalization. And again the court sided with the medical institution.

“We will appeal the court’s decision,” Rodion Smirnov does not give up. – There is an opinion from independent experts that Elena has no indication for hospitalization. However, the court refused to take it into account.

According to Smirnov, psychiatrists interpret his client’s beliefs about unnecessary medical interventions as delusional ideas.

– Before school and kindergarten, the child is advised to get vaccines against the most dangerous infections: measles, tetanus, mumps, diphtheria, rubella, polio, BCG. Also vaccinated against hepatitis A, chickenpox and whooping cough. There are also mandatory vaccinations for adults. All adults should receive an annual influenza vaccination and a booster vaccine against diphtheria and tetanus every 10 years. At the moment, all adults under 35 years of age require additional vaccination against measles,” comments Niso Odinaeva, chief freelance pediatrician of the Moscow Region Ministry of Health.

172Vaalis

My relatives are rebelling here. They say it's hard to pay rent. I pay for my grandmother’s electricity and phone, because she kind of needs it. Recently my grandmother came in to get a receipt, and then her daughter started a scandal about how hard it was to pay. This all threw me off and I said that I would only pay my 50%, I don’t use light, nor water. I was wrong? At the same time, my husband and I carry out all the current repairs, such as plumbing, electrics, if something is broken, and it was something bought by us or my parents, but completely different people use it, I also make claims about what is broken, and we drop everything and fix it.

121Ladybug

Good day to all!

Today we start the First Annual Poetry Competition of non-competitive poems.

I think that from the masterfully formulated title of the competition you understand that this time I accept poems that, for one reason or another, cannot take part in the main competition.

There is no specific theme, and there are no complicating elements.

If anyone wants to write something new and participate, then you are welcome!

So, I declare the First Annual Poetry Competition of non-competitive poems open!!!

P.S. Girls who have already sent non-competition poems, please send them again!!! The heat completely melted my brains, and I deleted all the old letters from the archive folder, forgetting to highlight and leave yours...

Let me remind you of the rules.

1. I am waiting for your letters to the address [email protected]

2. I accept poems from today until July 8(12 am Moscow time).

3. On July 9 I will create a topic for voting.

4. Reasonable size is welcome.

5. The number of poems from one author is not limited.

6. We do not use obscenities and pseudo-mats, because the rules of the forum must be respected.

7. I will announce the authors in a congratulations thread (I will create it on July 12), so I strictly ask you not to declassify yourself in advance.

8. For those who like to guess the authors, on July 10 there will be a “Guessing Game”.

9. Don’t forget to indicate your nickname on the forum or indicate that you are composing poems anonymously.

10. Review your creations for errors and typos.

11. All poems are checked for uniqueness

12. If you want your own annotation, then please send it along with your work.

How did you study in Rus'?

Knowledge Day Scenario

Presenter 1: Guys! Today is a special day for our country. All our people celebrate the Day of Knowledge. I congratulate you on this wonderful day, I want to wish you well and with interest in your studies. Now I will tell you how our ancestors studied in Rus'. The first mention of teaching children is found in the Russian chronicle of 988. It was this year that Prince Vladimir the Red Sun decided to convert to Christianity and convert all his subjects to this religion. It was then that the first schools appeared. Churches were built in cities and villages, and competent priests were needed. Vladimir ordered to take children from the “best people” and send them to “book education.” But the people at that time were still wild, they were not established in the new faith and were afraid of reading and writing. Students had to be recruited by force, and mothers, bringing their children, cried and wailed as if over the dead.

In 1028, the son of Prince Vladimir, Yaroslav the Wise, gathered 300 children in Novgorod and ordered them to “teach books.” This was the first big school.

Presenter 2:To travel back in time, “look” into the past and see a bygone life with your own eyes, you don’t need any special fantastic devices. It is enough to look into an ancient document - the most reliable carrier of information, which, like a magic key, unlocks the treasured door to the past. One of these documents was a book called “Stoglav” - a collection of resolutions of the Stoglav Cathedral, held with the participation of Ivan the 4th and representatives of the Boyar Duma in 1550-1551.

Gradually the number of schools grew, they opened at churches and monasteries (so-called parochial schools). Their teachers were priests (church ministers). The abundance of books translated from Greek that existed at that time shows that the school was doing its job - creating a reader and lover of education. The book was held in high esteem in Ancient Rus'. In the event of a fire, they tried to save the books first. “Books are the same rivers that water the universe,” they said in the old days. The son of Yaroslav the Wise - Svyatoslav - filled the storerooms of his palace with books, Vladimir Monomakh himself was a writer, and Monomakh's father Vsevolod knew five languages.

The invasion of the Mongol-Tatar conquerors in the 13th century slowed down the development of school and education in Rus' for several centuries. Only in the 16th century did a new rise in schooling begin.

By the 17th century there were already quite a lot of schools in both cities and villages, and their number was growing rapidly. This confirms the existence of books called “Azbukovnik”. These were collections of educational, moralizing and encyclopedic articles. The most widespread are educational alphabet books.

Presenter 1:Only boys were taught in schools - girls' lot was to do housework, where they could get by without the ability to read and write. Tuition had to be paid, so only children of wealthy parents could study. The group of students was called the “team”. Classes most often began on December 1, but the boy could enter school at any time. The students sat together, but the teacher worked with each student separately. There was also no specific training period. I learned to read, write, count and finished school. Everything depended on abilities.

The schools trained mainly priests - only the church needed literate people at that time. Since church services were conducted in Latin, it was taught to schoolchildren.

Latin at that time was already a “dead” language - there were no people on earth who spoke it. Prayers were read in Latin and religious books were written. Doctors used Latin so as not to cause unnecessary anxiety in patients, especially if the illness was quite serious. This “dead” language was taught in medieval schools.

First, the boys learned prayers by heart, repeating them after the teacher. Then they were taught to read the same prayers from the book. There were few books at that time, they were copied by hand, and they were very expensive. Therefore, there was only one book for the whole class, and with this single book the teacher passed from student to student.

Presenter 2:Let us follow the student who entered the school. So he put his hat on the shelf, bowed to the images, the teacher and the entire student “squad”. Here he had to spend the whole day, until the bell for the evening service, which was the signal for the end of classes. In the ABC book, instructions were written on this matter, which the students stubbornly repeated, thereby strengthening their reading skills.

In your house, having risen from sleep, washed your face,

Wipe the edge of the board well,

Continue in the veneration of holy images,

Bow low to your father and mother.

Go to school carefully

And lead your comrade,

Enter school with prayer,

Just go out there.

The teaching began with the answer to the lesson studied the day before. When the lesson was told by everyone, the entire “squad” performed a common prayer before further classes, in which they asked God: “Enlighten me and teach me the scriptures...”. Then they went to the headman for books and sat down at a long student table - each in a place indicated by the teacher.

The ABCs were not easy for children learning to read in the early 17th century. First we had to memorize the names of the letters. “A” - “Az”, “B” - “Beech”, “C” - “Lead”, “G” - “Verb”, “D” - “Good”... But it was even more difficult to put words together from letters. After all, according to the rules, it was necessary to call each letter of the word with a “full name”. By the time you get to the end of the word, you’ll forget where it started! Imagine yourself as students of a 17th century school: make words from the letters that I will show you.

(Show cards in sequence with the names of the letters that make up the word, and then the guys make up the word.)

Letters for cards:

“Good”, “He”, “Thinking”. (House).

“Sha”, “Kako”, “He”, “People”, “Az”. (School).

Schoolchildren wrote with quill quills on very cheap, loose paper, on which the pen constantly clung, leaving ink blots. To prevent the ink from spreading, we sprinkled the writing with fine sand from a jar.

Presenter 1:The first printed textbook for children was the ABC of 1574. It was compiled by Deacon Ivan Fedorov (the founder of book printing in Russia and Ukraine). Being an outstanding master of printing and a highly educated person, he set himself the goal: “... to scatter spiritual seeds throughout the universe and distribute this spiritual food to everyone in order.” Ivan Fedorov’s “ABC” contained not only letters, syllables, words, but also texts for reading, as well as Orthodox prayers. Fedorov’s “ABC” is also notable for the fact that it provided basic information on grammar: the composition of words, the spelling of unstressed vowels, the rules for declension of nouns and verb conjugation, etc. And at the end of the book, the author urged parents to teach their children to read and write. In 1578, Ivan Fedorov republished his ABC, containing information about the first teachers Cyril and Methodius. For many years, children learned to read and write from this book. Decades passed, and in 1634 the first primer was published, where the study of letters did not proceed in alphabetical order, but in a way that was convenient for the teacher and students. In 1692, the famous poet and outstanding educator Karion Istomin and artist Leonty Bunin created the first primer with pictures. In this primer, on each page it was shown how the same letter can be written in different ways.

Books were the property of the school, they were the main value, and therefore the teacher cultivated a respectful attitude towards it. There were certain rules when working with the book, which students had to strictly follow. These rules were the same for all schools of the 17th century. This is how it is written in the ABC book.

Keep your books well

And put it in a dangerous place;

When placing a book, close it with the seal facing up.

Don’t put the index tree in it at all.

Books to the elder for observance,

With prayer, bring

Taking the same thing in the morning,

With respect, take it.

Don’t unbend your books,

And don’t bend the sheets in them either.

Don't leave books on your seat,

But on the prepared table

Please supply.

No one cares about books anymore.

Such a person does not protect his soul.

Presenter 2:For sloppiness and school pranks, they were not only flogged with rods (thin rods soaked in water), but also forced to kneel on peas for several hours, leaving without lunch. And there were countless spanks and slaps during the lesson!

Flogging did not exhaust the arsenal of punishments, but it must be said that the rod was the last in that series. The naughty boy could be sent to a punishment cell, the role of which was successfully played by the school closet. There is also a mention in “Azbukovnik” of such a measure, which is now called “leave after school”:

“If someone doesn’t teach a lesson,

Such a student will not receive free leave from school...”

And one should not think that he used the power that the teacher possessed beyond all measure - good teaching cannot be replaced by skillful flogging. This was discussed in the book “Stoglav”, which was, in fact, a guide for teachers in teaching and raising children: “... not with rage, not with greed, not with anger, but with joyful fear and loving custom, and sweet teaching, and affectionate consolation.”

It is between the two poles that, perhaps, the path of education lay. And if the “sweet teaching” did not go well, then a “pedagogical tool” was used, “sharpening the mind, stimulating the memory.”

Presenter 1:For most of the day, students were constantly at school. Who helped the teacher if he needed to leave for urgent matters or just relax? To do this, in each class the teacher chose an assistant from among the students, called the headman. The role of the headman in the internal life of the then school was extremely important. After the teacher, the headman was the second person in the school; he was even allowed to replace the teacher himself. The headman had to monitor the progress of studies in the absence of the teacher and even had the right to punish those responsible for violating the order established in the school. The headman also listened to the lessons of younger schoolchildren, collected and handed out books, and monitored their safety and proper handling. He managed the heating, lighting and cleaning of the school.

The teacher chose the headman from among the older students who had diligent and favorable spiritual qualities in their studies. The elders carried out all the management of the school without any reporting to the teacher. On the contrary, the students were taught in every possible way to comradeship, to collective life in the “team”. There were cases when the teacher could not find the offender, and the “squad” did not hand him over, then punishment was announced to all students. Often the culprit, in order not to let the “squad” down, admitted his guilt and accepted the punishment without complaint.

It was difficult to read and write

To our ancestors in the old days.

And the girls were supposed to

Don't learn anything.

Only boys were trained.

Deacon with a pointer in his hand

I read books to them in a sing-song manner

In Slavic language.

A da B is like Az da Buki,

V - as Vedi, G - Verb.

And a teacher for science

On Saturdays I flogged them.

N. Konchalovskaya.

Books meet us in early childhood and accompany us throughout our lives. They force us to continuously improve ourselves so that we can become real people. Therefore, it was not without reason that our wonderful Russian writer Konstantin Georgievich Paustovsky said...

“A person who loves and knows how to read is a happy person. He is surrounded by many smart, kind and loyal friends. These friends are books.”

The summer holidays have just passed and flown by. Let's do a warm-up test of our knowledge. To do this, we will conduct a quiz.

The first task is “Quiz”.

1. What institutions were cultural centers in Rus' that spread education? (Monasteries, churches, they taught children to read and write.)

2. In the Cyrillic alphabet, each letter had a name (az, buki, vedi, and so on). What was the name of the letter “d” in Cyrillic? (Good).

3. What is the control of official authorities over the content, publication and distribution of printed materials called? (Censorship).

4. What is the name of a fictitious name that a person (writer, journalist) uses to replace his real name? (Pseudonym).

5. What is the name of the enterprise that prepares and produces printed materials: books, magazines, newspapers, and so on? (Publisher).

6. What are the names of notes, literary memories of past events made by a contemporary or participant in these events? (Memoirs).

7. What is the name of a printed publication containing a list of days of the year and events or memorable dates associated with these days? (Calendar).

8. What is the first and last name of the Russian pioneer printer? (Ivan Fedorov).

9. The name of this sacred book translated from Greek means “book”. (Bible).

10. “Reading is the best teaching.” Who is the author of these lines? (A.S. Pushkin).

11. Who is a bookworm? (Reader).

12. The second-hand book dealer is ... (Old bookseller).

The titles of many literary works contain adjectives. For example, “The Scarlet Flower” by S. T. Aksakov.

The task is to remember which adjectives are missing in the following titles of works.

A. Pogorelsky “... chicken.” (Black).

V. Gauf “... Muk.” (Small).

A. M. Volkov “Seven...kings.” (Underground).

H.K. Andersen “... the queen.” (Snow).

V.G. Gubarev “The Kingdom of...mirrors.” (Curves).

H. K. Andersen "...Duckling". (Nasty).

A.N. Tolstoy “...the key, or the Adventure of Pinocchio.” (Gold).

Brothers Grimm "... little tailor." (Brave).

E.L. Shvarts “The Tale of ... Time.” (Lost).

P.P.Bazhov “...hoof.” (Silver).

The next task is a cross blitz tournament : one team names a word, the other - its antonym, and vice versa. For example: white - black, sweet - salty, cry - laugh.

Another competition “The letter got lost.”

It is unknown how it happened

Only the letter got lost

Dropped into someone's house

And he rules it.

But I barely got there

The letter is mischievous,

Stranger Things

Things started to happen...

1. My uncle was driving without a vest (ticket),

He paid a fine for this.

2. At the top of the tower

Doctors scream day and night (rooks).

3. Noisy sticks (daws)

Started a fight

But they flew away instantly

Seeing a dog.

4. The hunter shouted: “Stop!

Doors (animals) They're chasing me!"

5. In front of the children

Rat (roof) painters are painting.

6. There are no roads in the swamp.

I'm into cats (bumps) hop and hop.

Assignment: “Intellectual game.”

- 1. Who wrote the poem "Borodino"?

- A.S. Pushkin;

- M.Yu. Lermontov;

- N.A. Nekrasov.

2. Which work of A.S. Pushkin begins with the words

“Near Lukomorye there is a green oak...”

- "Ruslan and Ludmila";

- "The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish";

- "Winter evening".

3. Which Russian classic was born in 1799?

- A.S. Pushkin;

- N.V. Gogol;

- A.P. Chekhov.

4. Which literary character suggested a dead cat as a cure for warts?

- Carlson;

- Pinocchio;

- Tom Sawyer.

5. Who was the third person Kolobok left?

- Bear;

- hare;

- fox.

6. This writer traveled to Lilliput, to Laputa, to Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glabbdobbrib, Japan and the country of the Houyhnhnms. Who is this?

- J. Verne;

- J. Swift;

- D. Defoe.

The task “Guess the descriptions of fairy-tale characters.”

- A very English and very well-mannered girl from the fairy tales of the writer and mathematics professor. A little boring. But it even decorates her a little. One day, chasing the White Rabbit, she jumped into his hole, which turned out to be a bottomless well that led her to a wonderful, wonderful land. Who is that girl? (Alice. L. Carroll “Alice in Wonderland”, “Alice Through the Looking Glass”.)

- The poor Arab youth from the Arabian Nights fairy tales. It was he who found the magic lamp with the Genie inside. This hero is brave and cheerful. An evil wizard became his enemy... Name this literary hero. (Aladdin from the fairy tale “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” from the book “A Thousand and One Nights.”)

- Self-confident, ignorant, but at the same time brave boy. Perhaps in the future he will become a good actor or even a chief director. No wonder he managed to rally around himself a whole group of like-minded actors who dealt with the evil director of the puppet theater. What is the boy's name? What about the theater directors? Who wrote the fairy tale and what is it called? (Pinocchio. Karabas-Barabas. A.N. Tolstoy “The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Pinocchio”)

- The most enviable fairytale bride. She can do everything: sow and grow a field of rye in one night, build a palace out of wax, turn into a dove or a duck... No one knows who she is or where she comes from. And now you must say her name. Difficult? I’ll give you a hint: she is the Wise, she is the Beautiful... (Vasilisa the Wise, Vasilisa the Beautiful from Russian folk tales.)

- Loves jam, loves honey and other goodies. His friend is a little pig. What is this hero's name? (Winnie the Pooh. A. Milne “Winnie the Pooh all-all-all”)

- The most fearless and kindest doctor in the world who understands the language of animals. Who is he? (Doctor Aibolit from the fairy tale of the same name by K.I. Chukovsky.)

- A very small and very beautiful girl. Not even a girl, but a fairy who was born in a flower. She traveled a lot by land, by air, by land. I’ve even been underground... Remember what this girl’s name was. (Thumbelina from the fairy tale of the same name by H. C. Andersen.)

- A very independent modern boy. Knows how to cook soup. Organized a farm in the village. The boy's household is prosperous and modern. It is hoped that in time he will become a wealthy farmer. And a dog and a cat will help him with this. Do you know this boy? Name him and the author of the book about him. (Uncle Fyodor. E.N. Uspensky “Uncle Fyodor, dog and cat.”)

- A sweet, hard-working, kind girl who met a real prince, fell in love with him and eventually became a princess. Who's that girl? (Cinderella from the fairy tale of the same name by Charles Perrault.)

- The most mysterious hero of Russian folk tales. Some kind of nonsense: a loaf is not a loaf, a pie is not a pie, something like a dry bun without raisins, but everyone wants to eat it. This hero did nothing good to anyone. And everyone feels sorry for him... What is his name? (Kolobok from a Russian folk tale.)

Now guys, let’s sum up our competition and find out who is the most well-read.

(Jury's word).

So, the title “The Most Intelligent Good Fellow of the Class” is awarded -......, “The Most Intelligent Fair Girl of the Class” -...... Certificates and books are awarded.

List of used literature:

- Dimiyanova V.E. Games with words / V.E. Dimiyanova // Read, learn, play. - 2008. - No. 9. - P.70-71.

- Zavyalova N.V. Welcome to the library! / N.V. Zavyalova // Read, study, play. - 2008. - No. 12. - P.34-36.

- Zavyalova N.V. “Reading is the best teaching” / N.V. Zavyalova // Read, study, play. - 2007. - No. 8. - P.70-74.

- From the history of Cossack education on the Don // Cossack school. History and modern Cossack education on the Don / comp. G.N. Rykov. - Rostov-on-Don: Rostizdat LLC, 2003. - P. 5-98.

- Karkacheva N.A. How we studied in Rus' / N.A. Karkachev // Read, study, play. - 2008. - No. 6. - P.11-14.

- Culture of Russia in the 16th century // History of Russia in the 16th-18th centuries: textbook / A.L. Yurganov, L.A. Katsva. - M.: MTsROS ROST, 1997. - P.70-90.

- Medieval school // I explore the world: History: Det. encycl. / N.V. Chudakova, A.V. Gromov. - M.: AST Publishing House LLC, 2002. - P. 271-272.

Prepared by N.V. Zadachina

Every year, schoolchildren sit down at their desks to once again “gnaw on the granite of science.” This has been going on for over a thousand years. The first schools in Rus' were radically different from modern ones: before there were no directors, no grades, or even division into subjects. the site found out how education was conducted in schools of past centuries.

Lessons from the breadwinner

The first mention of the school in ancient chronicles dates back to 988, when the Baptism of Rus' took place. In the 10th century, children were taught mainly at the priest’s home, and the Psalter and Book of Hours served as textbooks. Only boys were accepted into schools - it was believed that women should not learn to read and write, but do household chores. Over time, the learning process evolved. By the 11th century, children were taught reading, writing, counting and choral singing. “Schools of book learning” appeared - original ancient Russian gymnasiums, the graduates of which entered the public service: as scribes and translators.At the same time, the first girls' schools were born - however, only girls from noble families were accepted to study. Most often, the children of feudal lords and rich people studied at home. Their teacher was a boyar - the “breadwinner” - who taught schoolchildren not only literacy, but also several foreign languages, as well as the basics of government.

Children were taught literacy and numeracy. Photo: Painting by N. Bogdanov-Belsky “Oral Abacus”

Little information has been preserved about ancient Russian schools. It is known that training was carried out only in large cities, and with the invasion of Rus' by the Mongol-Tatars, it stopped altogether for several centuries and was revived only in the 16th century. Now schools were called “schools”, and only a representative of the church could become a teacher. Before starting a job, the teacher had to pass a knowledge exam himself, and the potential teacher’s acquaintances were asked about his behavior: cruel and aggressive people were not hired.

No ratings

The schoolchildren's day was completely different from what it is now. There was no division into subjects at all: students received new knowledge in one general stream. The concept of recess was also absent - during the whole day the children could only take one break, for lunch. At school, the children were met by one teacher, who taught everything at once - there was no need for directors and head teachers. The teacher did not grade the students. The system was much simpler: if a child learned and told the previous lesson, he received praise, and if he did not know anything, he was punished with rods.Not everyone was accepted into the school, but only the smartest and most savvy children. The children spent the whole day in classes from morning until evening. Education in Rus' proceeded slowly. Now all first-graders can read, but previously, in the first year, schoolchildren learned the full names of letters - “az”, “buki”, “vedi”. Second graders could form intricate letters into syllables, and it was only in the third year that children could read. The main book for schoolchildren was the primer, first published in 1574 by Ivan Fedorov. Having mastered letters and words, the children read passages from the Bible. By the 17th century, new subjects appeared - rhetoric, grammar, land surveying - a symbiosis of geometry and geography - as well as the basics of astronomy and poetic art. The first lesson on the schedule necessarily began with general prayer. Another difference from the modern education system was that children did not carry textbooks with them: all the necessary books were kept at school.

Available to everyone

After the reform of Peter I, a lot has changed in schools. Education acquired a secular character: theology was now taught exclusively in diocesan schools. By decree of the emperor, so-called numerical schools were opened in the cities - they taught only literacy and basic arithmetic. Children of soldiers and lower ranks attended such schools. By the 18th century, education became more accessible: public schools appeared, which even serfs were allowed to attend. True, forced people could study only if the landowner decided to pay for their education.

Previously, schools did not have divisions into subjects. Photo: Painting by A. Morozov “Rural Free School”

It was only in the 19th century that primary education became free for everyone. Peasants went to parish schools, where education lasted only one year: it was believed that this was quite enough for serfs. Children of merchants and artisans attended district schools for three years, and gymnasiums were created for nobles. Peasants were taught only literacy and numeracy. In addition to all this, the townspeople, artisans and merchants were taught history, geography, geometry and astronomy, and the nobles were prepared in schools to enter universities. Women's schools began to open, the program in which was designed for 3 years or 6 years - to choose from. Education became publicly accessible after the adoption of the corresponding law in 1908. Now the school education system continues to develop: in September, children sit down at their desks and discover a whole world of new knowledge - interesting and immense.

Turkic group of languages: peoples, classification, distribution and interesting facts Turkic language family of peoples

Turkic group of languages: peoples, classification, distribution and interesting facts Turkic language family of peoples Acetylene is the gas with the highest flame temperature!

Acetylene is the gas with the highest flame temperature! Clothes design (cut) system “M”

Clothes design (cut) system “M” What are some ways to preserve wild animals and plants?

What are some ways to preserve wild animals and plants? Literature test on the topic "Pantry of the Sun" (M

Literature test on the topic "Pantry of the Sun" (M Herbs: types of herbs, culinary uses and flavor combinations

Herbs: types of herbs, culinary uses and flavor combinations Present tenses (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous)

Present tenses (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous)