Family archive. Manifesto on the liberation of peasants Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom title

Serfdom turned into a brake on technological progress, which was actively developing in Europe after the Industrial Revolution. The Crimean War clearly demonstrated this. There was a danger of Russia turning into a third-rate power. It was by the second half of the 19th century that it became clear that maintaining the power and political influence of Russia was impossible without strengthening finances, developing industry and railway construction, and transforming the entire political system. Under the conditions of the dominance of serfdom, which itself could have existed for an indefinite period of time, despite the fact that the landed nobility itself was unable and not ready to modernize its own estates, this turned out to be practically impossible. That is why the reign of Alexander II became a period of radical transformations of Russian society. The Emperor, distinguished by his sound mind and a certain political flexibility, managed to surround himself with professionally competent people who understood the need for Russia's progressive movement. Among them, the tsar's brother, Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, brothers N.A. stood out. and D.A. Milyutin, Ya.I. Rostovtsev, P.A. Valuev and others.

By the second quarter of the 19th century, it had already become obvious that the economic capabilities of the landlord economy in meeting the increased needs for grain exports had been completely exhausted. It was increasingly drawn into commodity-money relations, gradually losing its natural character. Closely related to this was a change in the forms of rent. If in the central provinces, where industrial production was developed, more than half of the peasants had already been transferred to quitrent, then in the agricultural Central Black Earth and Lower Volga provinces, where commercial grain was produced, corvée continued to expand. This was due to the natural increase in the production of bread for sale on the landowners' farm.

On the other hand, the productivity of corvee labor has dropped noticeably. The peasant sabotaged the corvée with all his might and was burdened by it, which is explained by the growth of the peasant economy, its transformation into a small-scale producer. Corvee labor slowed down this process, and the peasant fought with all his might for favorable conditions for his farming.

Landowners sought ways to increase the profitability of their estates within the framework of serfdom, for example, transferring peasants to monthly labor: landless peasants, who were obliged to spend all their working hours in corvee labor, were given payment in kind in the form of a monthly food ration, as well as clothes, shoes, and necessary household utensils , while the landowner's field was cultivated with the master's equipment. However, all these measures could not compensate for the ever-increasing losses from ineffective corvee labor.

The quitrent farms also experienced a serious crisis. Previously, peasant crafts, from which quitrents were mainly paid, were profitable, giving the landowner a stable income. However, the development of crafts gave rise to competition, which led to a drop in peasant earnings. Since the 20s of the 19th century, arrears in quitrent payments began to grow rapidly. An indicator of the crisis of the landlord economy was the growth of estate debt. By 1861, about 65% of landowners' estates were pledged to various credit institutions.

In an effort to increase the profitability of their estates, some landowners began to use new methods of farming: they ordered expensive equipment from abroad, invited foreign specialists, introduced multi-field crop rotation, etc. But such expenses were only affordable for wealthy landowners, and under the conditions of serfdom, these innovations did not pay off, often ruining such landowners.

It should be especially emphasized that we are talking specifically about the crisis of the landlord economy, based on serf labor, and not the economy in general, which continued to develop on a completely different, capitalist basis. It is clear that serfdom hampered its development and prevented the formation of a wage labor market, without which the capitalist development of the country is impossible.

Preparations for the abolition of serfdom began in January 1857 with the creation of the next Secret Committee. In November 1857, Alexander II sent a rescript throughout the country addressed to the Vilna Governor-General Nazimov, which spoke of the beginning of the gradual liberation of the peasants and ordered the creation of noble committees in three Lithuanian provinces (Vilna, Kovno and Grodno) to make proposals for the reform project. On February 21, 1858, the Secret Committee was renamed the Main Committee for Peasant Affairs. A wide discussion of the upcoming reform began. Provincial noble committees drew up their projects for the liberation of peasants and sent them to the main committee, which, on their basis, began to develop a general reform project.

To revise the submitted projects, editorial commissions were established in 1859, the work of which was led by Comrade Minister of Internal Affairs Ya.I. Rostovtsev.

During the preparation of the reform, there were lively debates among landowners about the mechanism of liberation. The landowners of the non-black earth provinces, where the peasants were mainly on quitrent, proposed to allocate land to the peasants with complete liberation from the landowners' power, but with the payment of a large ransom for the land. Their opinion was most fully expressed in his project by the leader of the Tver nobility A.M. Unkovsky.

Landowners of the black earth regions, whose opinion was expressed in the project of the Poltava landowner M.P. Posen, they proposed to give only small plots to the peasants for ransom, with the goal of making the peasants economically dependent on the landowner - forcing them to rent land on unfavorable terms or work as farm laborers.

By the beginning of October 1860, the editorial commissions completed their activities and the project was submitted for discussion to the Main Committee for Peasant Affairs, where it was subject to additions and changes. On January 28, 1861, a meeting of the State Council opened and ended on February 16, 1861. The signing of the manifesto on the emancipation of the peasants was scheduled for February 19, 1861 - the 6th anniversary of the accession to the throne of Alexander II, when the emperor signed the manifesto “On the All-Merciful granting to serfs of the rights of free rural inhabitants and on the organization of their life,” as well as “Regulations on peasants emerging from serfdom,” which included 17 legislative acts. On the same day, the Main Committee “on the structure of the rural state” was established, chaired by Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, which replaced the Main Committee “on peasant affairs” and was called upon to carry out supreme supervision over the implementation of the “Regulations” of February 19.

According to the manifesto, peasants received personal freedom. From now on, the former serf peasant received the opportunity to freely dispose of his personality, he was granted some civil rights: the opportunity to move to other classes, enter into property and civil transactions in his own name, and open commercial and industrial enterprises.

If serfdom was abolished immediately, then the settlement of economic relations between peasants and landowners lasted for several decades. The specific economic conditions for the liberation of peasants were recorded in the “Charter Charters”, which were concluded between the landowner and the peasant with the participation of world intermediaries. However, according to the law, peasants were required to serve virtually the same duties as under serfdom for another two years. This state of the peasant was called temporarily obliged. In fact, this situation lasted for twenty years, and only by the law of 1881 were the last temporarily obliged peasants transferred to redemption.

An important place was given to the provision of land to the peasant. The law was based on the recognition of the landowner's right to all the land on his estate, including peasant plots. The peasants received the allotment not for ownership, but only for use. To become the owner of land, the peasant was obliged to buy it from the landowner. The state took on this task. The redemption was based not on the market value of the land, but on the amount of duties. The treasury immediately paid the landowners 80% of the redemption amount, and the remaining 20% had to be paid to the landowner by the peasants by mutual agreement (immediately or in installments, in money or in labor). The redemption amount paid by the state was treated as a loan to the peasants, which was then collected from them annually, for 49 years, in the form of "redemption payments" of 6% of this loan. It is not difficult to determine that in this way the peasant had to pay for the land several times more not only its real market value, but also the amount of duties that he bore in favor of the landowner. That is why the “temporarily obliged state” existed for more than 20 years.

When determining the norms for peasant plots, the peculiarities of local natural and economic conditions were taken into account. The entire territory of the Russian Empire was divided into three parts: non-chernozem, chernozem and steppe. In the chernozem and non-chernozem parts, two norms of allotments were established: the highest and the lowest, and in the steppe there was only one - the “decreed” norm. The law provided for a reduction of the peasant allotment in favor of the landowner if its pre-reform size exceeded the “higher” or “decree” norm, and an increase if the allotment did not reach the “higher” norm. In practice, this has led to the fact that cutting off land has become the rule, and trimming the exception. The burden of the “cuts” for the peasants was not only their size. The best lands often fell into this category, without which normal farming became impossible. Thus, the “cuts” turned into an effective means of economic enslavement of the peasants by the landowner.

Land was provided not to an individual peasant household, but to the community. This form of land use excluded the possibility of a peasant selling his plot, and its rental was limited to the community. But, despite all its shortcomings, the abolition of serfdom was an important historical event. It not only created conditions for the further economic development of Russia, but also led to a change in the social structure of Russian society and created the need for further reform of the political system of the state, which was forced to adapt to new economic conditions. After 1861, a number of important political reforms were carried out: zemstvo, judicial, city, military reforms, which radically changed Russian reality. It is no coincidence that domestic historians consider this event a turning point, the line between feudal Russia and modern Russia.

ACCORDING TO THE “SHOWER REVISION” OF 1858

Landowner serfs - 20,173,000

Appanage peasants - 2,019,000

State peasants -18,308,000

Workers of factories and mines, equated to state peasants - 616,000

State peasants assigned to private factories - 518,000

Peasants released after military service - 1,093,000

HISTORIAN S.M. SOLOVIEV

“Liberal speeches began; but it would be strange if the first, main content of these speeches were not the liberation of the peasants. What other liberation could one think of without remembering that in Russia a huge number of people are the property of other people, and slaves are of the same origin as their masters, and sometimes of higher origin: peasants of Slavic origin, and masters of Tatar, Cheremis, Mordovian origin, not to mention Germans? What kind of liberal speech could be made without remembering this stain, the shame that lay on Russia, excluding it from the society of European civilized peoples?

A.I. HERZEN

“Many more years will pass before Europe understands the course of development of Russian serfdom. Its origin and development are a phenomenon so exceptional and unlike anything else that it is difficult to believe in it. How, in fact, can one believe that half the population of the same nationality, gifted with rare physical and mental abilities, was enslaved not by war, not by conquest, not by a coup, but only by a series of decrees, immoral concessions, vile claims?

K.S. AKSAKOV

“The yoke of the state was formed over the land, and the Russian land became, as it were, conquered... The Russian monarch received the meaning of a despot, and the people - the meaning of a slave-slave in their land”...

“IT’S MUCH BETTER FOR THIS TO HAPPEN ABOVE”

When Emperor Alexander II came to Moscow for the coronation, the Moscow Governor-General Count Zakrevsky asked him to calm the local nobility, excited by rumors about the upcoming liberation of the peasants. The Tsar, receiving the Moscow provincial leader of the nobility, Prince Shcherbatov, with district representatives, told them: “There are rumors that I want to announce the liberation of serfdom. This is unfair, and as a result there were several cases of peasants disobeying the landowners. I won't tell you that I'm completely against it; We live in such an age that this must happen over time. I think that you are of the same opinion as me: therefore, it is much better for this to happen from above than from below.”

The matter of the liberation of the peasants, which came before the State Council, in its importance I consider a vital issue for Russia, on which the development of its strength and power will depend. I am sure that all of you, gentlemen, are just as convinced as I am of the benefits and necessity of this measure. I also have another conviction, namely, that this matter cannot be postponed, which is why I demand from the State Council that it be completed in the first half of February and can be announced by the beginning of field work; I entrust this to the direct responsibility of the chairman of the State Council. I repeat, and it is my absolute will that this matter be ended now. (...)

You know the origin of serfdom. It did not exist with us before: this right was established by autocratic power and only autocratic power can destroy it, and this is my direct will.

My predecessors felt all the evils of serfdom and constantly strived, if not for its direct destruction, then for a gradual limitation of the arbitrariness of landowner power. (...)

Following the rescript given to Governor General Nazimov, requests began to arrive from the nobility of other provinces, which were answered with rescripts addressed to governors general and governors of similar content with the first. These rescripts contained the same main principles and foundations and allowed us to proceed to the matter on the same principles I indicated. As a result, provincial committees were established, which were given a special program to facilitate their work. When, after the given period of time, the work of the committees began to arrive here, I allowed the formation of special Editorial Commissions, which were supposed to consider the projects of the provincial committees and do the general work in a systematic manner. The Chairman of these Commissions was first Adjutant General Rostovtsev, and after his death Count Panin. The editorial commissions worked for a year and seven months, and, despite the criticisms, perhaps partly fair, to which the commissions were subjected, they completed their work in good faith and presented it to the Main Committee. The main committee, chaired by my brother, worked with tireless activity and zeal. I consider it my duty to thank all the members of the committee, and my brother in particular, for their conscientious efforts in this matter.

Views on the work presented may vary. That’s why I listen to all different opinions willingly; but I have the right to demand one thing from you, that you, putting aside all personal interests, act as state dignitaries invested with my trust. When starting this important task, I did not hide from myself all the difficulties that awaited us, and I do not hide them now, but, firmly trusting in the mercy of God, I hope that God will not leave us and will bless us to complete it for future prosperity dear Fatherland to us. Now, with God’s help, let’s get down to business.

MANIFESTO FEBRUARY 19, 1861

BY GOD'S GRACE

WE, ALEXANDER THE SECOND,

EMPEROR AND AUTOCRET

ALL-RUSSIAN

KING OF POLISH, GRAND DUKE OF FINNISH

and so on, and so on, and so on

We announce to all our loyal subjects.

By God's providence and the sacred law of succession to the throne, having been called to the ancestral all-Russian throne, in accordance with this calling we have made a vow in our hearts to embrace with our royal love and care all our loyal subjects of every rank and status, from those who nobly wield a sword in defense of the Fatherland to those who modestly work with a craft tool, from those undergoing the highest government service to those plowing a furrow in the field with a plow or plow.

Delving into the position of ranks and conditions within the state, we saw that state legislation, while actively improving the upper and middle classes, defining their duties, rights and benefits, did not achieve uniform activity in relation to serfs, so called because they were partly old by laws, partly by custom, they are hereditarily strengthened under the power of landowners, who at the same time have the responsibility to organize their well-being. The rights of landowners were until now extensive and not precisely defined by law, the place of which was taken by tradition, custom and the good will of the landowner. In the best cases, from this came good patriarchal relations of sincere, truthful trusteeship and charity of the landowner and good-natured obedience of the peasants. But with a decrease in the simplicity of morals, with an increase in the variety of relationships, with a decrease in the direct paternal relations of landowners to peasants, with landowner rights sometimes falling into the hands of people seeking only their own benefit, good relations weakened and the way opened to arbitrariness, burdensome for the peasants and unfavorable for them. well-being, which was reflected in the peasants by their immobility towards improvements in their own life.

Our ever-memorable predecessors saw this and took measures to change the situation of the peasants for the better; but these were measures, partly indecisive, proposed to the voluntary, freedom-loving action of landowners, partly decisive only for some areas, at the request of special circumstances or in the form of experience. Thus, Emperor Alexander I issued a decree on free cultivators, and our late father Nicholas I issued a decree on obligated peasants. In Western provinces, inventory rules determine the allocation of land to peasants and their duties. But the regulations on free cultivators and obliged peasants were put into effect on a very small scale.

Thus, we are convinced that the matter of changing the situation of serfs for the better is for us the testament of our predecessors and the lot given to us through the course of events by the hand of providence.

We began this matter with an act of our trust in the Russian nobility, in its devotion to its throne, proven by great experiences, and its readiness to make donations for the benefit of the Fatherland. We left it to the nobility itself, at their own invitation, to make assumptions about the new structure of life of the peasants, and the nobles were to limit their rights to the peasants and raise the difficulties of transformation, not without reducing their benefits. And our trust was justified. In the provincial committees, represented by their members, invested with the trust of the entire noble society of each province, the nobility voluntarily renounced the right to personality of serfs. In these committees, after collecting the necessary information, assumptions were made about the new structure of life for people in a state of serfdom and about their relationship to the landowners.

These assumptions, which turned out to be varied, as could be expected from the nature of the matter, were compared, agreed upon, put into the correct composition, corrected and supplemented in the Main Committee for this matter; and the new regulations on landowner peasants and courtyard people drawn up in this way were considered in the State Council.

Having called on God for help, we decided to give this matter executive movement.

By virtue of these new provisions, serfs will in due course receive the full rights of free rural inhabitants.

The landowners, while retaining the right of ownership of all the lands belonging to them, provide the peasants, for established duties, with their permanent homestead for permanent use and, moreover, to ensure their life and fulfill their duties to the government, a certain amount of field land and other land determined in the regulations.

Using this land allotment, the peasants are obliged to fulfill the duties specified in the regulations in favor of the landowners. In this state, which is transitional, the peasants are called temporarily obliged.

At the same time, they are given the right to buy out their estates, and with the consent of the landowners, they can acquire ownership of field lands and other lands allocated to them for permanent use. With such acquisition of ownership of a certain amount of land, the peasants will be freed from their obligations to the landowners on the purchased land and will enter into a decisive state of free peasant owners.

A special provision for domestic servants defines for them a transitional state, adapted to their occupations and needs; upon expiration of a two-year period from the date of publication of this regulation, they will receive full exemption and immediate benefits.

On these main principles, the provisions drawn up determine the future structure of peasants and courtyard people, establish the order of public peasant governance and indicate in detail the rights granted to peasants and courtyard people and the responsibilities assigned to them in relation to the government and to the landowners.

Although these provisions, general, local and special additional rules for some special areas, for the estates of small landowners and for peasants working in landowner factories and factories, are, if possible, adapted to local economic needs and customs, however, in order to preserve the usual order there, where it represents mutual benefits, we allow the landowners to make voluntary agreements with the peasants and conclude conditions on the size of the peasants’ land allotment and the following duties in compliance with the rules established to protect the inviolability of such agreements.

As a new device, due to the inevitable complexity of the changes required by it, cannot be carried out suddenly, but will require time, approximately at least two years, then during this time, in order to avoid confusion and to respect public and private benefit, existing to this day in the landowners On estates, order must be preserved until, after proper preparations have been made, a new order will be opened.

To achieve this correctly, we considered it good to command:

1. To open in each province a provincial presence for peasant affairs, which is entrusted with the highest management of the affairs of peasant societies established on landowners' lands.

2. To resolve locally misunderstandings and disputes that may arise during the implementation of the new provisions, appoint peace mediators in the counties and form county peace congresses from them.

3. Then create secular administrations on the landowners' estates, for which, leaving rural societies in their current composition, open volost administrations in significant villages, and unite small rural societies under one volost administration.

4. Draw up, verify and approve a statutory charter for each rural society or estate, which will calculate, on the basis of local situation, the amount of land provided to peasants for permanent use, and the amount of duties due from them in favor of the landowner both for the land and and for other benefits from it.

5. These statutory charters shall be carried out as they are approved for each estate, and finally put into effect for all estates within two years from the date of publication of this manifesto.

6. Until the expiration of this period, peasants and courtyard people remain in the same obedience to the landowners and unquestioningly fulfill their previous duties.

Paying attention to the inevitable difficulties of an acceptable transformation, we first of all place our hope in the all-good providence of God protecting Russia.

Therefore, we rely on the valiant zeal of the noble class for the common good, to whom we cannot fail to express from us and from the entire Fatherland well-deserved gratitude for their selfless action towards the implementation of our plans. Russia will not forget that it voluntarily, prompted only by respect for human dignity and Christian love for one’s neighbors, renounced serfdom, which is now being abolished, and laid the foundation for a new economic future for the peasants. We undoubtedly expect that it will also nobly use further diligence to implement the new provisions in good order, in the spirit of peace and goodwill, and that each owner will complete within the boundaries of his estate the great civil feat of the entire class, arranging the life of the peasants and his servants settled on his land people on terms beneficial to both parties, and thereby give the rural population a good example and encouragement to accurately and conscientiously fulfill state duties.

The examples in mind of the generous care of the owners for the welfare of the peasants and the gratitude of the peasants to the beneficent care of the owners confirm our hope that mutual voluntary agreements will resolve most of the difficulties inevitable in some cases of applying general rules to the various circumstances of individual estates, and that in this way the transition from the old order to the new and in the future mutual trust, good agreement and unanimous desire for common benefit will be strengthened.

For the most convenient implementation of those agreements between owners and peasants, according to which they will acquire ownership of field lands along with their estates, the government will provide benefits, on the basis of special rules, by issuing loans and transferring debts lying on the estates.

We rely on the common sense of our people. When the government's idea of abolishing serfdom spread among peasants who were not prepared for it, private misunderstandings arose. Some thought about freedom and forgot about responsibilities. But general common sense has not wavered in the conviction that, according to natural reasoning, one who freely enjoys the benefits of society must mutually serve the good of society by fulfilling certain duties, and according to Christian law, every soul must obey the powers that be (Rom. XIII, 1), give everyone their due, and especially to whom it is due, lesson, tribute, fear, honor; that rights legally acquired by landowners cannot be taken from them without decent compensation or voluntary concession; that it would be contrary to all justice to use land from the landowners and not bear the corresponding duties for it.

And now we expect with hope that the serfs, with the new future opening up for them, will understand and gratefully accept the important donation made by the noble nobility to improve their life.

They will understand that, having received for themselves a more solid foundation of property and greater freedom to dispose of their household, they become obligated to society and to themselves to supplement the beneficialness of the new law with the faithful, well-intentioned and diligent use of the rights granted to them. The most beneficial law cannot make people prosperous if they do not take the trouble to arrange their own well-being under the protection of the law. Contentment is acquired and increased only by unremitting labor, prudent use of strength and means, strict frugality and, in general, an honest life in the fear of God.

Those who carry out preparatory actions for the new structure of peasant life and the very introduction to this structure will use vigilant care to ensure that this is done with a correct, calm movement, observing the convenience of the time, so that the attention of farmers is not diverted from their necessary agricultural activities. Let them carefully cultivate the land and collect its fruits, so that later from a well-filled granary they can take seeds for sowing on land for permanent use or on land acquired as property.

Sign yourself with the sign of the cross, Orthodox people, and call upon us God’s blessing on your free labor, the guarantee of your home well-being and public good. Given in St. Petersburg, on the nineteenth day of February, in the year from the birth of Christ one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one, the seventh of our reign.

On February 19, 1861, Russian Emperor Alexander II signed a manifesto on the complete abolition of serfdom, and also approved the “Regulations on Peasants...”, receiving the popular nickname “Liberator” for this.

Although this manifesto gave peasants civil and personal freedoms (for example, the right to marry, trade, or go to court), they were still limited in economic rights and freedom of movement. In addition, peasants continued to be the only class subject to conscription and subject to physical punishment.

At the same time, the land plot remained the property of the landowner, and the peasants received only a field allotment and a settled estate, for which they were obliged to bear responsibility, paying with work or money. According to the new law, peasants were allowed to buy out an estate or plot. In this case, they became peasant owners, gaining complete independence. The ransom amount was equal to the annual quitrent amount multiplied by seventeen.

Also, to help the peasants, the state organized a special “redemption operation”, the essence of which was as follows. After establishing an allotment, the government gave the landowner 80% of its value, and the remaining 20% was attributed to the peasant, who agreed to pay it off within 49 years.

Peasants united into so-called rural communities, which, in turn, united into volosts. To make redemption payments, all peasants were bound by a mutual guarantee, and the use of field land was common.

Household people who did not plow the land were temporarily obliged to do so for two years, after which they were allowed to register with a city or rural society.

The agreement between peasants and landowners was set out in a “charter”, and the position of a conciliator was established to deal with various disputes. In general, the leadership of the “passage” of the reform was entrusted to the presence of peasant affairs located in the provinces.

The peasant reform created all the conditions for the transformation of labor into a commodity. Market relations began to develop, which are an indicator of a capitalist state. The consequence of the manifesto on the abolition of serfdom was the emergence of new social strata of the population - the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

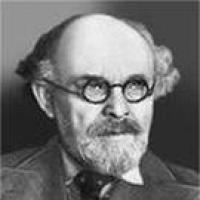

Alexander II, who signed the Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom, was called the Tsar the Liberator. He was not called the Great, like Peter or Catherine, but his reforms were defined as great. Having ascended the throne in 1855, Alexander II received a difficult legacy. The defeat in the Crimean War showed an obvious military-technical lag and the dilapidation of the entire economic system. Society, which had experienced thirty years of stagnation, demanded decisive steps to renew the country. Not being a reformer by vocation, the young monarch became one in response to the challenges of the time. According to contemporaries, with the accession of Alexander II, a “thaw” began in the socio-political life of Russia.

The conclusion of the Paris Peace in March 1856 is the first of his most important decisions. In August of the same year, he declared an amnesty for the Decembrists, Petrashevites, and participants in the Polish uprising of 1830-1831, and suspended recruitment for three years. By his decision, the Supreme Censorship Committee was liquidated, and the discussion of government affairs began to be open. Finally, immediately after the coronation, the new monarch announced the need to abolish serfdom. “The existing order of ownership of souls cannot remain unchanged,” he said, addressing representatives of the nobles of the Moscow province. “It’s better to start destroying serfdom from above than to wait for the time when it begins to destroy itself from below.” For four years, a special Secret Committee on Peasant Affairs met regularly under the chairmanship of the emperor. At the cost of compromise, by overcoming a number of contradictions between representatives of different strata of society, it was possible to create fundamental documents on peasant reform.

On February 19, 1861, they were signed by Alexander II in St. Petersburg, and two days later they were unveiled in a solemn ceremony in Moscow, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin. The news, according to eyewitnesses, did not make much of an impression on ordinary people - only at the Bolshoi Theater the audience after the evening performance shouted “Hurray!” She sang the national anthem “God Save the Tsar” twice. “With the acquisition of ownership of a certain amount of land,” the manifesto emphasized, “the peasants are freed from their duties to the landowners on the purchased land and will enter the decisive state of free peasant owners.” At the same time, they could “carry out free trade,” “leave their place of residence,” “enter the service,” and “acquire ownership of real and movable property.”

The peasants received not only personal freedom, but also land. The landowners were paid for it by the state, which thus became the creditor of a huge number of former serfs. The peasants had to pay off the state within 49 years. Moreover, the majority of them, over 85%, bought the land after 20 years. And in 1905, the government canceled the remaining debt.

To consider complaints from peasants against landowners and resolve disputes between them, “middlemen” were established, appointed from among local nobles. Leo Tolstoy worked actively and enthusiastically in this position - when settling disputes and conflicts, he conducted the matter “in the most cold-blooded and conscientious manner.” The economic growth that Russia experienced after 1861 is the main result of the peasant reform. This is due to the fact that the acquired personal freedom allowed a huge mass of landless or land-poor peasants to go to the cities to earn money. The emergence of an entire army of inexpensive and hard-working labor gave impetus to industrialization, which significantly improved the country's economy - the growth of the gross national product was at an unprecedented pace.

Starting with the liberation of 23 million serfs, Alexander II essentially began to reform the entire Russian life. One of his most important reforms was the “Regulations on provincial and district zemstvo institutions”, published on January 1, 1864. Local government bodies - zemstvos - were elected by all classes for a three-year term and were responsible for education, healthcare, food supplies, the quality of roads, insurance, and veterinary care. The judicial reform of 1864 also played a huge role, thanks to which the third, judicial, power was separated from the executive and legislative powers.

In civil and criminal proceedings, the principles of transparency and competition between the parties have been introduced. In criminal cases, the determination of guilt was left to jurors chosen from representatives of all classes. The military reform begun by Alexander II in 1862 lasted for a decade and a half. Military districts were formed, the officer corps was improved and updated, a military education system was created, and the technical re-equipment of the army was carried out. In 1874, Alexander II approved the law on the transition to universal military service. All men at the age of 20, regardless of class, were subject to conscription into the army and navy.

In the history of Russia, Alexander II was one of the most beloved monarchs by the people. Alas, it was precisely this circumstance that largely became the cause of his death. The chances of rousing the people to revolution and coming to power would be reduced to a minimum, socialists and anarchists believed, if the emperor carried his reforms to the end. It is unlikely that a people who have received so much will want to rebel. And therefore, the Narodnaya Volya party constantly developed plans to assassinate the emperor. The excessive, in the opinion of many, liberalism of Alexander II prevented him from taking tough measures against various revolutionary-minded elements - even after they began outright terror: seven attempts on his life alone. The eighth, fatal one, happened on March 1, 1881, when the terrorist Ignatius Grinevitsky threw a bomb at the feet of the emperor. The mortally wounded Alexander II was transferred to the Winter Palace, where he died.

Boris Kustodiev. "The Liberation of the Peasants (Reading the Manifesto)." Painting from 1907

"I want to be alone with my conscience." The Emperor asked everyone to leave the office. On the table in front of him lay a document that was supposed to turn the entire Russian history upside down - the Law on the Liberation of Peasants. They had been waiting for him for many years, the best people of the state fought for him. The law not only eliminated the shame of Russia - serfdom, but also gave hope for the triumph of goodness and justice. Such a step for a monarch is a difficult test, for which he has been preparing all his life, from year to year, since childhood...

His teacher Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky spared neither effort nor time to instill in the future Emperor of Russia a sense of goodness, honor, and humanity. When Alexander II ascended the throne, Zhukovsky was no longer around, but the emperor retained his advice and instructions and followed them until the end of his life. Having accepted Russia, exhausted by the Crimean War, he began his reign by giving Russia peace.

Historians often reproach the emperors of the first half of the 19th century for not trying to implement or trying with all their might to complicate the abolition of serfdom. Only Alexander II decided to take this step. His reform activities are often accused of being half-hearted. Was it really easy for the monarch to carry out reforms if his support, the Russian nobility, did not support his endeavors. Alexander II required enormous courage to balance between the possibility of a threat from the noble opposition, on the one hand, and the threat of a peasant revolt, on the other.

To be fair, we note that there have been attempts to carry out peasant reform before. Let's turn to the background. In 1797, Emperor Paul I issued a decree on a three-day corvee, although the wording of the law remained unclear, whether the law did not allow or simply did not recommend the use of peasant labor in corvee more than three days a week. It is clear that the landowners were for the most part inclined to adhere to the latter interpretation. His son, Alexander I, once said: “If education had been at a higher level, I would have abolished slavery, even if it cost me my life.” Nevertheless, after Count Razumovsky approached him in 1803 for permission to free fifty thousand of his serfs, the tsar did not forget about this precedent, and as a result, in the same year, the decree “On Free Plowmen” appeared. According to this law, landowners received the right to release their peasants if it would be beneficial to both parties. During the 59 years of the law, the landowners released only 111,829 peasants, of which 50 thousand were serfs of Count Razumovsky. Apparently, the nobility was more inclined to hatch plans for the reconstruction of society rather than begin its implementation with the liberation of their own peasants.

Nicholas I in 1842 issued the Decree “On Obligated Peasants,” according to which peasants were allowed to be freed without land, providing it for the performance of certain duties. As a result, 27 thousand people became obligated peasants. The need to abolish serfdom was beyond doubt. “The state of serfdom is a powder magazine under the state,” wrote the chief of gendarmes A.H. Benkendorf in a report to Nicholas I. During the reign of Nicholas I, preparations for peasant reform were already underway: the basic approaches and principles for its implementation were developed, and the necessary material was accumulated.

But Alexander II abolished serfdom. He understood that he had to act carefully, gradually preparing society for reforms. In the first years of his reign, at a meeting with a delegation of Moscow nobles, he said: “There are rumors that I want to give freedom to the peasants; it's unfair and you can say it to everyone left and right. But, unfortunately, a feeling of hostility between peasants and landowners exists, and as a result there have already been several cases of disobedience to the landowners. I am convinced that sooner or later we must come to this. I think that you are of the same opinion as me. It is better to begin the destruction of serfdom from above, rather than wait for the time when it begins to be destroyed of its own accord from below.” The emperor asked the nobles to think and submit their thoughts on the peasant issue. But I never received any offers.

Then Alexander II turned to another option - the creation of a Secret Committee “to discuss measures to organize the life of the landowner peasants” under his personal chairmanship. The committee held its first meeting on January 3, 1857. The committee included Count S.S. Lanskoy, Prince Orlov, Count Bludov, Minister of Finance Brock, Count Adlerberg, Prince V.A. Dolgorukov, Minister of State Property Muravyov, Prince Gagarin, Baron Korf and Y.I. Rostovtsev. He managed the affairs of the Butkov committee. Committee members agreed that serfdom needed to be abolished, but warned against making radical decisions. Only Lanskoy, Bludov, Rostovtsev and Butkov spoke out for the real liberation of the peasants; the majority of committee members proposed only measures to alleviate the situation of the serfs. Then the emperor introduced his brother, Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, into the committee, who was convinced of the need to abolish serfdom.

The Grand Duke was an extraordinary person and thanks to his active influence, the committee began to develop measures. On the advice of the Grand Duke, Alexander II took advantage of the situation in the Baltic provinces, where landowners were dissatisfied with the existing fixed norms of corvee and quitrent and would like to abolish them. Lithuanian landowners decided that it was better for them to completely abandon the ownership of serfs, retaining land that could be rented out profitably. A corresponding letter was drawn up to the emperor, and he, in turn, handed it over to the Secret Committee. The discussion of the letter went on for a long time in the committee; the majority of its members did not share this idea, but Alexander ordered to “approve the good intentions of the Lithuanian nobles” and create official committees in the Vilna, Kovno and Grodno provinces to prepare proposals for organizing peasant life. Instructions were sent to all Russian governors in case local landowners “would like to resolve the matter in a similar way.” But no takers showed up. Then Alexander sent a rescript to the St. Petersburg Governor General with the same instructions to create a committee.

In December 1857, both royal rescripts were published in newspapers. So, with the help of glasnost (by the way, this word came into use at that time), the matter moved forward. For the first time, the country began to openly talk about the problem of the abolition of serfdom. The Secret Committee ceased to be such, and at the beginning of 1858 it was renamed the Main Committee for Peasant Affairs. And by the end of the year, committees were already working in all provinces.

On March 4, 1858, the Zemstvo Department was formed within the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the preliminary consideration of projects coming from the provinces, which were then transferred to the Main Committee. Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs A.I. Levshin was appointed chairman of the Zemstvo Department; the most important role in his work was played by the head of the department, Y.A. Solovyov, and the director of the economic department, N.A. Milyutin, who soon replaced Levshin as deputy minister.

At the end of 1858, reviews finally began to arrive from provincial committees. To study their proposals and develop general and local provisions for the reform, two editorial commissions were formed, the chairman of which was appointed by the emperor as the chief head of military educational institutions, Ya. I. Rostovtsev. General Rostovtsev was sympathetic to the cause of liberation of the peasants. He established a completely trusting relationship with Milyutin, who, at the request of the chairman, attracted liberal-minded officials and public figures, staunch supporters of the reform Yu.F. Samarin, Prince Cherkassky, Ya.A. Solovyov and others, to the activities of the commissions. They were opposed by members of the commissions who were opponents of the reform, among whom Count P.P. Shuvalov, V.V. Apraksin and Adjutant General Prince I.F. Paskevich stood out. They insisted on maintaining land ownership rights for landowners, rejected the possibility of providing land to peasants for ransom, except in cases of mutual consent, and demanded that landowners be given full power on their estates. Already the first meetings took place in a rather tense atmosphere.

With the death of Rostovtsev, Count Panin was appointed in his place, which was perceived by many as a curtailment of activities to liberate the peasants. Only Alexander II was unperturbed. To his aunt Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, who expressed concerns about this appointment, he replied: “You don’t know Panin; his convictions are the exact execution of my orders.” The Emperor was not mistaken. Count Panin strictly followed his instructions: not to change anything during the preparation of the reform, to continue to follow the intended course. Therefore, the hopes of the serf owners, who dreamed of cardinal concessions in their favor, were not destined to come true.

At the same time, at meetings of the editorial commissions, Panin behaved more independently, trying to gradually, very carefully make concessions to landowners, which could lead to significant distortions of the project. The struggle between supporters and opponents of the reform sometimes became quite serious.

On October 10, I860, the emperor ordered the closure of the editorial commissions, which had worked for about twenty months, and the activities of the Main Committee to be resumed again. Due to the illness of the chairman of the committee, Prince Orlov, Alexander II appointed his brother, Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, to this post. In a small committee, several groups formed, none of which could achieve a clear majority. At the head of one of them, which included the chief of gendarmes, Prince V.A. Dolgorukov, Minister of Finance A.M. Knyazhevich and others, was M.N. Muravyov. These committee members sought to reduce land allotment rates. A special position in the committee was occupied by Count Panin, who challenged many of the provisions of the editorial draft, and Prince P.P. Gagarin, who insisted on the liberation of peasants without land. For a long time, Grand Duke Constantine was unable to gather a solid majority of supporters of the draft editorial commissions. To ensure an advantage, he tried, by resorting to the power of persuasion and making some concessions, to win Panin over to his side, and he still succeeded. Thus, an absolute majority of supporters of the project was formed - fifty percent plus one vote: five members of the Main Committee against four.

Many were waiting for the onset of 1861. Grand Duke Constantine noted in his diary: “January 1, 1861. This mysterious year of 1861 began. What will he bring us? With what feelings will we look at it on December 31? Should the peasant question and the Slavic question be resolved in it? Isn't this alone enough to call it mysterious and even fatal? Maybe this is the most important era in the thousand-year existence of Russia?

The last meeting of the Main Committee was chaired by the Emperor himself. Ministers who were not members of the committee were invited to the meeting. Alexander II stated that when submitting the project for consideration by the State Council, he would not tolerate any tricks or delays, and set the deadline for completion of the consideration on February 15, so that the content of the resolutions could be published and communicated to the peasants before the start of field work. “This is what I desire, demand, command!” - said the emperor.

In a detailed speech at a meeting of the State Council, Alexander II gave historical information about attempts and plans to resolve the peasant issue in previous reigns and during his reign and explained what he expected from members of the State Council: “Views on the presented work may be different. Therefore, I will listen to all different opinions willingly, but I have the right to demand one thing from you: that you, putting aside all personal interests, act not as landowners, but as state dignitaries, invested with my trust.”

But even in the State Council, approval of the project was not easy. Only with the support of the emperor did the decision of the minority receive the force of law. Preparations for the reform were nearing completion. By February 17, 1861, the State Council completed its consideration of the project.

On February 19, 1861, on the sixth anniversary of his accession, Alexander II signed all the reform laws and the Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom.

On March 5, 1861, the Manifesto was read in churches after mass. At the divorce ceremony in the Mikhailovsky Manege, Alexander II himself read it to the troops.

The manifesto on the abolition of serfdom provided peasants with personal freedom. From now on, they could not be sold, bought, donated, or relocated at the request of the landowner. Peasants now had the right to own property, freedom to marry, could independently enter into contracts and conduct legal cases, could acquire real estate in their own name, and had freedom of movement.

The peasant received a land allotment as a means of personal freedom. The size of the land plot was established taking into account the terrain and was not the same in different regions of Russia. If previously a peasant had more land than the fixed allotment for a given area, then the “extra” part was cut off in favor of the landowner. Such “segments” made up a fifth of all lands. The allotment was given to the peasant for a ransom. The peasant paid a quarter of the ransom amount to the landowner in a lump sum, and the rest was paid by the state. The peasant had to repay his debt to the state within 49 years. Before purchasing the land from the landowner, the peasant was considered “temporarily obligated”, paid the landowner a quitrent and worked off corvée. The relationship between the landowner and the peasant was regulated by the Charter.

The peasants of each landowner's estate united into rural societies - communities. They discussed and resolved their general economic issues at village meetings. The village headman, elected for three years, had to carry out the decisions of the assemblies. Several adjacent rural communities made up the volost. The volost elder was elected at a general meeting, and he subsequently performed administrative duties.

The activities of rural and volost administrations, as well as the relationships between peasants and landowners, were controlled by global intermediaries. They were appointed by the Senate from among the local noble landowners. Conciliators had broad powers and followed the directions of the law. The size of the peasant allotment and duties for each estate should have been determined once and for all by agreement between the peasants and the landowner and recorded in the Charter. The introduction of these charters was the main activity of the peace mediators.

When assessing the peasant reform, it is important to understand that it was the result of a compromise between landowners, peasants and the government. Moreover, the interests of the landowners were taken into account as much as possible, but there was probably no other way to liberate the peasants. The compromise nature of the reform already contained future contradictions and conflicts. The reform prevented mass protests by peasants, although they still took place in some regions. The most significant of them were the peasant uprisings in the village of Bezdna, Kazan province, and Kandeevka, Penza province.

And yet, the liberation of more than 20 million landowners with land was a unique event in Russian and world history. The personal freedom of peasants and the transformation of former serfs into “free rural inhabitants” destroyed the previous system of economic tyranny and opened up new prospects for Russia, creating the opportunity for the broad development of market relations and the further development of society. The abolition of serfdom paved the way for other important transformations, which were to introduce new forms of self-government and justice in the country, and push for the development of education.

The undeniably great merit in this is Emperor Alexander II, as well as those who developed and promoted this reform, fought for its implementation - Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, N.A. Milyutin, Y.I. Rostovtsev, Yu.F. Samarin, Y.A. Solovyov and others.

References:

Great Reform. T. 5: Reform figures. - M., 1912.

Ilyin, V.V. Reforms and counter-reforms in Russia. - M., 1996.

Troitsky, N.A. Russia in the 19th century. - M., 1997.

B. Kustodiev. Liberation of the peasants

1861 On March 3 (February 19, Old Style), Emperor Alexander II signs the Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom and the Regulations on peasants emerging from serfdom.

Preparations for the reform began with the creation in 1857 of a secret Committee on Peasant Affairs to develop measures to improve the situation of the peasantry. They tried not to use the words “liberation.” In 1858, provincial peasant committees began to open, and the main, secret committee became public. All these organizations developed reform projects, which were then submitted to the editorial commissions for consideration. Yakov Ivanovich Rostovtsev became the chairman of the commissions.Count Ya.I.Rostovtsev

The three main directions of the projects were fundamentally different: the project of the Moscow governor was directed against the liberation of the peasants, offering only an improvement in conditions, as originally formulated, the second direction, led by the St. Petersburg committee, proposed to free the peasants without the possibility of buying out the land, and the third group of projects insisted on the liberation of the peasants with earth.

After reviewing the projects, deputies were invited from the provinces. The deputies of the first convocation had very little access to the decision of affairs and were eventually dissolved. Members of the editorial commissions, not without reason, believed that provincial representatives would try to look after their own benefit exclusively to the detriment of the interests of the peasants.

In addition, the implementation of the reform according to the original plan could be hindered by the fact that after Rostovtsev’s death in 1860, Count V.N. took his place. Panin, who has a reputation as an opponent of liberal reforms.

The highest decree ordered that the creation of the reform project be completed by the day the emperor ascended the throne.

On March 1, the State Council adopts the project, and on March 3 (February 19, old style), Alexander II signs the legislative acts presented to him.

For all the enthusiasm with which the release of the manifesto was greeted, there were also many dissatisfied ones. Most peasants were interested not so much in the civil liberties granted to them by the reform, but rather in the land on which they could work to feed their families. According to the Regulations, issued simultaneously with the Manifesto, it was assumed that peasants would buy out land plots, since all land remained the full property of the landowners. Before the ransom, the peasants remained “temporarily obligated,” which meant that they were actually just as dependent.

Turkic group of languages: peoples, classification, distribution and interesting facts Turkic language family of peoples

Turkic group of languages: peoples, classification, distribution and interesting facts Turkic language family of peoples Acetylene is the gas with the highest flame temperature!

Acetylene is the gas with the highest flame temperature! Clothes design (cut) system “M”

Clothes design (cut) system “M” What are some ways to preserve wild animals and plants?

What are some ways to preserve wild animals and plants? Literature test on the topic "Pantry of the Sun" (M

Literature test on the topic "Pantry of the Sun" (M Herbs: types of herbs, culinary uses and flavor combinations

Herbs: types of herbs, culinary uses and flavor combinations Present tenses (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous)

Present tenses (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous)