Russian philosophers, public and government figures. Pogodin, Mikhail Petrovich Basic provisions submitted for defense

Political conservatism of M. P. Pogodin

November 23, 2005 marks the 205th anniversary of the birth of the Russian publicist, editor, historian and ideologist of the patriotic, monarchist school of thought, one of the creators of the famous triad of “Orthodoxy. Autocracy. Nationalities” M.P. Pogodin (1800-1875). In today's society, devoid of solid moral guidelines, there is a need to develop a stable national ideology. In this regard, the figure of M.P. The weather is of particular interest to us.

Unfortunately, until recently the name Pogodin was consigned to oblivion. His main works, both journalistic and historical in nature, as well as poetry, drama and historical prose, have not yet been published. But besides this, he is interesting to us today as an ideologist of Russian national development, who expressed the essence of the national idea.

He was born into the family of a serf, the manager of the Moscow houses of P.A. Saltykov, who was released by him in 1806. He received his first education at home, learning to read and write from his home clerk. Since 1814 - in the Moscow provincial gymnasium. Having graduated from the gymnasium as the first student, he entered the literature department of Moscow University (1818), where the greatest influence on him was made by prof. R.F. Timkovsky, I.A. Game and especially A.F. Merzlyakov.

His interest in German literature was also stimulated by his rapprochement with F.I. Tyutchev. F.I. himself Tyutchev, to the best of his ability, helped develop Pogodin’s talent. Friendship with Tyutchev contributed to a rapprochement with his literary mentor S.E. Raich, who invited him in December 1822 to his literary society. In addition, he, together with Tyutchev, was a member of the society of wise men and actively participated in it.

Here he meets Moscow literary youth and in particular S.P. Shevyrev, V.P. Titov, who introduce him to the circle of philosophical and aesthetic interests of the wise. At the same time, Pogodin gravitates towards the “Schellingian” wing of society, perceiving the ideas of the German philosopher in relation to aesthetics and the theory of history from J. Bachmann and F. Ast and remaining alien to the natural philosophy of F. Schelling.

At the end of 1825, Pogodin compiled the literary almanac “Urania. Pocket book for 1826." (1825), which was intended to become the “Moscow answer” to the Decembrist St. Petersburg “Polar Star” by A.A. Bestuzhev and K.F. Ryleeva. Pogodin managed to attract A.F. to cooperation. Merzlyakova, F.I. Tyutcheva, E.A. Boratynsky, P.A. Vyazemsky, who delivered him poems by A.S. Pushkin. However, the basis was formed by the participants of the collection and Moscow wise men, i.e. here for the first time the range of literary names and aesthetic aspirations that characterized Moscow literature of the 1820s and 30s was presented.

Starting from 1827-30s, he published the magazine “Moskovsky Vestnik”, where he attracted A.S. Pushkin. Despite the formal failure, "Moskovsky Vestnik" was an expression of the range of ideas emerging in the 20s among the younger generation of Moscow writers - a kind of "Moscow romanticism", having adopted the paradigm of German romanticism of literary theory and philosophy. The role of historical materials was determined by the Schellingian understanding of history as the science of “self-knowledge” of humanity and romanticism. Pogodin’s “historical aphorisms and questions” (1827) had a programmatic interest in national history, which determined his Schellingian hobbies and desire for a philosophical “theory of history.”

Without any doubt, Pogodin was one of the best and deepest Russian thinkers who preserved and developed our Russian identity, and who, together with F.I. Tyutchev one of the brightest exponents of the Russian imperial idea.

By origin, he was the son of a serf peasant and, like his namesake M.V. Lomonosov, Mikhail Petrovich came to one of the capitals in search of knowledge. In 1841 elected full member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Pogodin's creativity is extremely multifaceted. He is the author of a number of major historical works, the historical drama “Marfa Posadnitsa”, a number of stories, literary criticism and other works.

Pogodin's interests are in historical studies. In the early 1830s, he collaborated in the publications of N. Nadezhdin “Rumor” and “Telescope”, publishing here, in addition to stories and essays, various notes, as well as articles on current Polish topics. According to Pogodin, the history of Poland, full of turmoil and “anarchy,” proves the need for Russian domination, but the conclusion about the importance of studying and popularizing Polish history and language made his position ambiguous. Pogodin’s position apparently also reflected conversations with A.S. Pushkin.

Pogodin saw the main task of history as being “the guardian and guardian of public peace.” In journalism of the 1830s - early 1850s, he stood firmly on patriotic and conservative traditions. Mikhail Petrovich went down in the history of Russian social thought as a supporter of the ideology of the official nationality, represented by the triune formula “Orthodoxy. Autocracy. Nationality”, and also took an active part in the development of this theory.

Pogodin’s worldview was very eclectic, in some of its elements simply contradictory and incompatible. In general, he can be called a democratic monarchist. Coming from the people, rooting for the people, dreaming of their liberation from serfdom and, on the other hand, being completely alien to the aristocratic elite and noble arrogance, he was nevertheless not a liberal and revolutionary. Like the Slavophiles, he developed the idea of the voluntary calling of rulers by the people (he adhered to the Varangian-Norman theory regarding the first Russian princes), but if the Slavophiles emphasized that the people, having given up power, retained the power of public opinion and advice, then Pogodin, in much the same way as F.I. Tyutchev forgot this principle and completely immersed himself in the activities of the state authorities.

A significant role in the development of the theory of official nationality belonged to the young Pogodin. His blood connection with the people and his deep understanding of Russian Orthodoxy made the Russian national idea especially close to him. The idea of the special character of Russian history in comparison with European history was formed by him in a lecture he gave under his fellow Minister of Public Education S.S. Uvarov and fully approved by him.

Having immersed himself in the study of Russian chronicles, Pogodin became convinced of the profound difference between the course of Russian history and Western European history. F.I. came to similar thoughts. Tyutchev, being at that time in the West on a diplomatic mission. In one of his speeches, which were largely of an official nature, Pogodin expressed the essence of the Russian nationality. This is how Pogodin explained the reason for the absence in Russia of laws and institutions similar to Western European ones: “... Every resolution must certainly have its own seed and its own root... it is not always possible to replant other people’s plants, no matter how lush and brilliant they are. healthy".

The adoption of Orthodoxy, which develops a “special side of faith,” and the voluntary “calling of the Varangians,” who, in contrast to the conquest in the West, laid the foundation for Russian statehood, predetermined the specific nature of the attitude of the supreme power to the nation and its role in all spheres of life, in particular national education .

On a number of issues (the independence of the Russian historical process, the role of Orthodoxy and some others), Pogodin’s views were close to the views of the Slavophiles.

His views were imbued with the idea of providentialism. Domestic history presented a clear example of the leading role of Divine Providence. She predicted a brilliant future for the Fatherland, noting that Russia was being led by “the finger of God... to some high goal.” Particular importance was attached to the ethnic unity of the population of the empire, speaking the same language and professing the same faith.

Pogodin further propagated the ideas of the official nationality - both in lectures and on the pages of the press. However, while adhering to conservative views on the state structure of Russia, the scientist at the same time was a staunch supporter of the abolition of serfdom, and based his commitment to autocracy primarily on the educational mission that he associated with it. And in this regard, the positions of both M.P. Pogodin, and F.I. Tyutchev became the forerunner of the doctrine of the people's monarchy, the main developers of which later became L.N. Tikhomirov, V.V. Rozanov, M.O. Menshikov, I.A. Ilyin, and, of course, I.L. Solonevich.

An important component of Pogodin’s historical and political concept is the idea of the pan-Slavic roots of Russian history and culture, which predetermined sympathy for the ideas of the “Slavic revival” and the formation of pan-Slavic views. Having traveled around Germany in 1835, visiting Vienna, he provided S.S. Uvarov “Report”, in which he reported news of the scientific life of Germany and talked about meetings with “figures of the Slavic revival” - V. Ganka, Safarik, V. Karadzic. The Slavic theme becomes a significant part of Pogodin’s literary and social activities.

Finally, in a subsequent report to the Minister of Education about a new trip abroad in 1839, he first formulated the newest Pan-Slavist doctrine. Having given an outline of the situation of the Slavs and Austria, the historian outlined a program for Slavic cultural and linguistic “rapprochement”, supplementing it with political assumptions - about the need to change policy towards Austria and unite the Slavs under the scepter of Russia.

After the trip of 1839, Pogodin finally decided to publish “The Moskvitian”, having received the “blessing” of Zhukovsky and the approval of Gogol, and official permission thanks to the support of S.S. Uvarov (with the active participation of another developer of the concept of official nationality and friend of his youth, S.P. Shevyrev). The name and concept of the magazine reflected Pogodin’s “Muscovophile” views.

After the trip of 1839, Pogodin finally decided to publish “The Moskvitian”, having received the “blessing” of Zhukovsky and the approval of Gogol, and official permission thanks to the support of S.S. Uvarov (with the active participation of another developer of the concept of official nationality and friend of his youth, S.P. Shevyrev). The name and concept of the magazine reflected Pogodin’s “Muscovophile” views.

In this magazine, Pogodin continued to promote the ideas of the official nationality. The humanities professors leading Moskvityanin were inspired by the idea of the uniqueness of Russia, Russian history, and the Russian people, and, protesting against the admiration of the West, in a polemical impulse they often turned to exaggeration and one-sidedness.

Pogodin and Tyutchev were often classified by contemporaries as Slavophiles. And indeed, there was a lot in common between them. There are noticeable conservative elements in Slavophilism: adherence to national Russian traditions, Orthodoxy, patriarchal morals, monarchy (in the form of the ideal of the zemstvo tsar), a negative attitude towards rationalism and the general nature of Western European enlightenment. However, both of them, in many ways broader than the early Slavophiles, looked at both Russian history as a whole and contemporary events (in particular, this was reflected in the more objective attitude of F.I. Tyutchev and M.P. Pogodin to the ambiguous and contradictory acts of Peter I).

To a greater extent, Pogodin’s views largely coincided with the views of F.I. Tyutchev in the 50s. During the Crimean War, he wrote “Historical and political letters and notes in the continuation of the Crimean War of 1853-56.” His letter “A View of Russian Politics in the Present Century,” where he sharply criticized the legitimist principle of Russian politics, turned out to be especially popular. This letter was determined by the fact that it (along with Tyutchev’s political articles) clearly formulated the thesis about the opposing interests of Europe and Russia as a representative of the Eastern Russian-Slavic world. The initial indignation that Tyutchev had immediately after the Crimean War spilled out emotionally into the epitaph on the death of Nicholas I. However, after communicating with M.P. Pogodin, Tyutchev himself comes to the idea that the tsar himself was a victim of deception and betrayal on the part of his entourage.

In general, his views on the socio-political situation changed depending on the developing situation in the country. The beginning of a military conflict arouses Pogodin's patriotic enthusiasm, but the failures of the Russian army and Nicholas I's disapproving reviews of his letters change their subject matter. Thus, in the letter “On the influence of foreign policy on domestic policy,” sharply criticizing “the protective direction of the current reign, which, without taking into account the peculiarities of national history and national character and impeding Russian original enlightenment, only strengthens bureaucratic “ulcers,” Pogodin proclaims the only cure for them publicity. Later, the thinker’s position came into conflict with official foreign policy; repeated attempts to publish political letters in 1856 - 58 failed. These letters turned out to be very radical both in tone and in substance. In them, Pogodin suffers deeply “for the people who work, shed blood, and bear all the burdens.”

He paints a terrible image of Russia, “hungry, thirsty, yearning, not knowing what to do with its strength, squandering God’s gifts fornication...”. Pogodin sees the reason for this situation as “a false fear of having a Western revolution!” In this regard, he directly says that “Mirobo is not scary for us, but Emelka Pugachev is scary for us; Ledru-Rollin and all the communists will not find adherents among us, and any village will open its mouth before Nikita the Pustosvyat.”

Pogodin leaves no stone unturned on the foreign policy of Nicholas I and Nesselrode. He, like F.I. Tyutchev, denounces the “pro-Austrian” orientation of the cabinet, the policy of the “gendarme of Europe”, as a result of which “the people hated Russia... and now happily seized the first opportunity that opened up to shake it in any way.”

In addition, Pogodin directly calls for the abolition of serfdom, expressing the famous argument that was later made in the speech of Alexander II to the Moscow nobility (“it is better to effect liberation from above than from below”). This anxiety is confirmed by his statement: “If Shamil, Pugachev or Razin appeared in some Arkhangelsk or Vologda wilderness, he could pass, preaching a triumphal march to several provinces and cause more trouble for the government than the rebellion of Catherine’s time...” The apparent “calmness” of the people is deceptive: “The ignorant glorify it, Russia’s silence, but this silence of a cemetery, rotting and stinking physically and morally... Such an order will lead us not to glory, not to happiness, but into the abyss!” And then there is the demand for material progress (“the establishment of railways”), the speedy development of education, and indispensable publicity (“a medicine that our Western policy forbade us under threat of execution”). Immediately there was an awareness of the need to “rebuild the state mechanism and get rid of a large part of the apparatus.

Pogodin, while working on the “Letters,” by his own admission, “thought that the time had finally come for the fulfillment of his most sincere, cherished hopes,” and therefore invariably sent each of the newly written anti-Nicholas pamphlets... to the imperial court! And there they were approved: in November 1854, Pogodin, while in St. Petersburg, was twice granted an audience with the heir (two months later he became Alexander II).

“Letters and articles on Russia’s policy towards the Slavic peoples,” published abroad on Tyutchev’s advice in 1858, caused sharp discontent among the authorities, and the article “The past year in Russian history” became the reason for the closure of the Parus newspaper.

Just like M.P. Pogodin, F.I. Tyutchev is aware of the relationship between foreign policy and domestic policy, and also more deeply perceives the inevitability of the defeat of such a policy by K.V. Nesselrode and his entourage, despite all the sacrifices of the Russian people.

In his articles, the Russian historian and thinker Pogodin proceeded from the need to take into account the unique identity, lifestyle, and culture of the Russian and other Slavic peoples. Pogodin believed that the basis of Russian history essentially lies in “the eternal beginning, the Russian spirit.”

Creativity M.P. Pogodin was filled with Slavic conciliarity, that is, the feeling and awareness of the spiritual reciprocity of Slavic brothers worthy of freedom and unity. “We love the Slavs, but they also love us, that’s all: there’s no point in politics meddling here,” the scientist exclaimed. Therefore, Mikhail Petrovich repeatedly called on the Slavs to mutual agreement.

The exceptional breadth of his range of interests, activities, and acquaintances turn him into one of the central figures of Russian literary and social life of the mid-19th century, and his archive into a kind of encyclopedia of this remarkable era in Russia for its talents.

9) Russian writers. 1800-1917. Dictionary. T.4. – M: 1999.10) Russian worldview. Dictionary. – M: 2003.

11) Russian-Slavic civilization. – M: 1998.

12) V.O. Klyuchevsky. M.P. Pogodin. Collection op. in 9 volumes. T.7. – M: 1989.

13) Full name Buslaev. Pogodin as a professor. – In his book “My Leisure”, part 2. – 1886.

14) D. Yazykov. M.P. Pogodin. – M:1901.

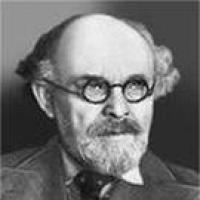

Historian Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin. Artist V.G. Perov. 1872

Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin (1800 - 1875) - Russian historian, writer, collector.

The son of a serf serf, Count I.P. Saltykov, his “housekeeper”, who received his freedom in 1806. Until the age of ten, Pogodin was educated at home, and already at this early stage of his life a passion for learning began to develop in him; At that time he knew only Russian literacy.

From 1810 to 1814, Pogodin was raised by a friend of his father, Moscow typographer A. G. Reshetnikov. Here the teaching went more systematically and successfully, but during these four years a general historical event occurred - the war of 1812 between Russia and France. Pogodin’s father’s house perished in the flames of the Moscow fire, and the Pogodin family had to seek salvation, along with other residents of the burning capital, in one of the provincial cities of central Russia. The Pogodins moved to Suzdal.

From 1814 to 1818, Pogodin studied at the Moscow, then the only, provincial gymnasium.

After graduating from high school, he entered the literature department of Moscow University. At the gymnasium and at the university, Pogodin became even more addicted to reading and began to diligently study Russian history, mainly under the influence of the first eight volumes of Karamzin’s “History of the Russian State” that appeared in the year of his admission to the university and nine years before that, the beginning of the Russian translation of Shletser’s “ Nestor." These two works were of decisive importance in the scientific works and views of Pogodin: he became a convinced admirer of the Russian historiographer and the first and most ardent of Russian historians to follow the historical criticism of Schletser and his “Norman theory” of the origin of Rus'.

In 1821 he graduated from Moscow University and taught there.

In his master's thesis “On the Origin of Rus'” (1825), he substantiated the Norman theory of the emergence of Russian statehood. He studied ancient Russian and Slavic history, the processes of enslavement of the Russian peasantry, and the reasons for the rise of Moscow. Defended his doctoral dissertation “On the Chronicle of Nestor” (1834). He discovered and introduced into scientific circulation a number of important historical sources and monuments of Russian literature. His “Historical Aphorisms” (1827) became famous, in which he shares with the reader his thoughts on the subject and method of history. In 1846 - 1859 “Research, remarks and lectures by M.P. Pogodin on Russian history” were published. And in 1871 “Ancient Russian history before the Mongol yoke.”

He joined the literary and philosophical circle of “lyubomudrov”, which included Dmitry Venevitinov, Ivan Kireevsky, Vladimir Odoevsky and others.

He published the magazine “Moskovsky Vestnik” from 1827 to 1830. At first, the Moskovsky Vestnik brilliantly presented poetry with the names of A. S. Pushkin, D. A. Venevitinov, E. A. Baratynsky, D. V. Davydov, N. M. Yazykov, A. S. Khomyakov, but with In 1828, Pushkin and his friends lost interest in the Moskovsky Vestnik, fiction was replaced by scientific articles that were too specialized for a wide range of readers, the magazine lost subscribers and ceased to exist. In 1841 - 56 together with S.P. Shevyrev, Pogodin publishes the magazine “Moskvityanin”. Pogodin’s characteristic assertion of the originality of Russian history, the magazine’s interest in antiquity and folk life attract Slavophiles to him, who periodically appear on its pages. Pogodin also edited the first six issues of the Russian Spectator, and from 1837 the Russian Historical Collection.

Author of the stories “The Beggar” (1825), “As it comes around, so it responds” (1825), “The Light Brown Braid” (1826), “The Betrothed” (1828), “Sokolnitsky Garden” (1829), “Adele” (1830) , “Criminal” (1830), “Vasiliev’s Evening” (1831), “Black Sickness”, “Bride at the Fair” and others, as well as the historical tragedy in verse “Martha, Posadnitsa of Novgorod” (1830).

He collected a significant collection of icons, copper and silver crosses, various antiquities, coins and medals, weapons, manuscripts, early printed books, autographs of Russian and foreign figures of science, literature, art, as well as state, military, political, and church leaders. The collection is known as the "Ancient Vault".

Most of this collection is kept in museum collections. Part of the collection was acquired for the Public Library in St. Petersburg and the Hermitage.

By the end of his life, for his contribution to the development of historical science and the promotion of historical knowledge, he was awarded many scientific and honorary titles: ordinary professor, academician, member of the Moscow Archaeological Society, honorary member of the Agram Society of Antiquities, chairman of the Slavic Charitable Committee, member of the Moscow Societies of History and Antiquities Russian and lovers of Russian literature, actual state councilor, member of the Moscow City Duma.

He was buried in the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow.

M.P. Pogodin (1800-1875)

The name of Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin - a scientist-historian and teacher, collector of antiquities, who created the famous "Tree Depository", publicist and playwright, publisher of "Moskovsky Vestnik" (1828-1830) and "Moskovityanin" (1841-1856) was widely known in scientific, literary and public circles in Russia in the 19th century.

Pogodin was the son of the serf peasant Count I.P. Saltykov, who received his freedom in 1806. He is a graduate of the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow University (1821). After defending his master's thesis in 1825, he began lecturing on Russian and world history at the moral and political department of the university. Since 1828, Pogodin has been adjutant at the department of general history. In 1833 he was elected an ordinary professor, and from 1835 - head of the department of Russian history, created according to the university charter of 1835. In 1844, due to a conflict with the trustee of Moscow University S.G. Stroganov, Pogodin resigned and focused his attention on journalistic and publishing activities, continuing his scientific research on the history of Russia. He worked a lot in the Society of Russian History and Antiquities and in the Society of Lovers of Russian Literature. In 1841 he was elected an ordinary academician of the Imperial Academy of Sciences.

Attitude towards Pogodin of contemporaries and descendants

Pogodin enjoyed respect and authority among his contemporaries. Among his friends were A.S. Pushkin and N.V. Gogol, D.V. Venevitinov and F.V. Odoevsky, A.S. Khomyakov and KS. Aksakov, S.P. Shevyrev and others. His name is often mentioned in the memoirs of his contemporaries. I. D. Kavelin, D. A. Korsakov, S. M. wrote about his scientific and pedagogical work. Soloviev, V.O. Klyuchevsky, G.V. Plekhanov and others N.P. Barsukov compiled a 22-volume biographical chronicle, unprecedented in its scope, “The Life and Works of M.P. Pogodin” However, his assessments as a scientist, teacher and person are ambiguous. Many noted the “subtlety of his criticism of the source,” his diligence in collecting materials, but at the same time, the lack of a “broad general view,” due to which the results of his activities were “limited, having only particular significance.”

His political beliefs fit into the concepts of “autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationality” and had, according to P.N. Miliukova, “protective character.” However, another researcher of socio-political activities Pogodina D.A. Korsakov did not consider it possible to clearly define its direction: “Pogodin was neither a conservative, nor a legitimist, nor a nationalist - he was a supporter of Russian political consent, as it had developed in life and history.”

Soviet historiography, based on an assessment of the creativity of scientists from a class position, unambiguously classified Pogodin as an “apologist of autocracy”, called him “Uvarov’s slave,” a conservative who did not have any profound influence on the general course of scientific and historical knowledge. In the last decade, historiographers have sought to give an unbiased assessment of his scientific and pedagogical activities, to show the complexity and versatility of his personality.

The range of scientific, cultural, and social interests of Pogodin was wide. But the main subject of his work was Russian history, the history of ancient and medieval Rus'. He is the author of a number of major studies: “The Origin of the Varangians and Rus'”, “Historical Aphorisms”, “Nestor. Historical-critical discussion about the beginning of Russian chronicles”, “Research, comments and lectures on Russian history” (vol. 1-7), “Ancient Russian history before the Mongol yoke”, etc.

Theoretical foundations of Pogodin’s concept

“The time in which we live,” wrote Pogodin, “taught us a lot and offered us previously unheard-of questions,” to which history should give answers. Many new sources have been found, and “significant changes” have occurred in general concepts and in historical science itself. Karamzin paved the “high road” in finding the truth in the events of the past. From him Pogodin learned “both goodness and the language of history,” “love for the fatherland, respect for folk traditions.” According to Pogodin, he was “imbued with the spirit of criticism” from A. Schletser. He clarified his historical positions in polemics with M.T. Kachenovsky, N.A. Polev, G. Evers, S.M. Soloviev.

Pogodin was aware of the latest European historical and philosophical ideas. Like many of his contemporaries, he was interested in the philosophy of Schelling and the ideas of romanticism. The scientist tried to comprehend national ideals and traditions, the place of the Russian people in human history, and to determine his own idea of the meaning and content of history. “Russian history,” he wrote, “is ourselves, our flesh and blood, the embryo of our own thoughts and feelings... By studying history, we study ourselves, we reach our self-knowledge, the highest point of national and personal education. This is the book of our existence." Consequently, Pogodin determined the subject of research: instead of political history, it is necessary to study the “spirit of the people,” “the history of the human mind and heart,” i.e. phenomena, primarily personal, everyday, religious, artistic: to “put out” the workers and architects who built Russia. He represented the actions of the “human spirit” in the form of a chain of events, where each ring “necessarily holds on to all the previous ones and, in turn, holds on to all the subsequent ones.” This harmony is subject to certain conditions and laws. To foresee it is the task of the historian. For this, Pogodin considered it important to study all, even the most insignificant incidents, their causes, to “catch the sounds”, then you can read history the way “deaf Beethoven read the score.” Based on this, Pogodin defined one of his main principles for studying the past: “collecting, purifying, distributing events.”

“The connection and course of events,” he continued, is the concept of God’s government, “an instructive spectacle of popular actions aimed at one goal of the human race, a goal indicated by good Providence.” But the secret of Providence is “hardly accessible to man.” Everything that happens should have happened. Every phenomenon in the chain of events is a miracle. At the same time, Pogodin argued that “we are not blind instruments of Higher powers, we act as we want, and free will is the first condition of human existence, our distinctive property.” But just as it is impossible for a person to penetrate into the secret of Providence, it is also impossible to trace “the intentions and actions of a person according to the laws of freedom.” The historian cannot answer the question of why everything turned out this way and not otherwise. He can only feel “God’s plan,” and, Pogodin noted, “not at the university, not in the library,” but “in the depths of his soul,” and intuitively approach it. In combining “religious instinct” and scientific research, he sees an opportunity to get closer to the truth. “A mind illuminated by faith will be strengthened by the sciences” - this is the way for him to understand the past.

Pogodin, convinced of the identity of the laws of the natural and spiritual world, was one of the first in Russian historical science to come to the conclusion that the search for truth in history can be the same as in other sciences, i.e. historical science can use study techniques used in other sciences. He associated the image of a historian with the image of a naturalist who explores all classes and species that exist in nature. Likewise, the historian, when dealing with the most complex categories - man, people, state, the development of which is associated with a whole complex of properties - must study all events in detail, identify the conditions and roots of their appearance, the gradual, organic nature of their development. This is precisely what makes historical science, Pogodin concluded, truly a science.

Pogodin called his research method mathematical. He first outlined its content in his master's thesis “On the Origin of Rus'. The mathematical conclusion, as he imagined it, is the only path leading to the goal, while others “carry away to the side, back, or at least slow down progress.” It was by this method that he studied Russian chronicles, he proved the reliability of the information they reported, confirmed the antiquity of their origin, and on this basis presented the most ancient period of Russian history.

Pogodin compared the work of a historian with the work of a collector, for example a numismatist, who sorts coins by place, time of minting, by the material from which they are made, and, like V.N. Tatishchev, with the work of an architect. “If we want to build a building,” wrote Pogodin, “first of all, we must prepare the materials - burn the bricks, cut the stones.” It was this “dirty” work that he took on himself, presenting in his studies “the plan, the facade of the building” both for himself and for future times. Only after the construction of such a “foundation of history” was it possible, according to Pogodin, to move on to analysis and conclusions, that is, to the second type of historical work - “narration.” So far, in science, he stated, not enough has been done in the field of research in order to move on to the presentation of history itself. Existing theories do not reflect the essence of facts: “No theory,” the scientist wrote, “even the most brilliant, no system, even the most ingenious, is durable, I repeat for the hundredth time, before beings and deeds are gathered, purified, tested, and established” (facts real). This was precisely the main content of Pogodin’s works. He called his “Research, Notes and Lectures on Russian History” a book “with a thousand references and authentic words from various information”, “clearing the field” of history so that others would have the opportunity to make whatever considerations they want and move on. Higher-minded researchers would find in these writings “the necessary knowledge for systems and theories.”

Pogodin considered it necessary to precede the writing of a general history of Russia with the study of its individual periods, for example, the Norman, Mongolian, Moscow, and he himself gave examples of such study. He also considered it important to conduct a detailed study of individual groups of the population: boyars, merchants, service people, smerds, relations between princes, etc.

The beginning of Russian history

“Russia is a huge world,” Pogodin wrote. She possesses immeasurable spaces and riches of “material and spiritual forces.” Finding out how this “colossus” was formed, how “all these forces were concentrated, how all these forces are preserved in one hand” is the main task of historical science. To solve it, the scientist suggests turning to the study of the beginning of history, i.e. the origins of the formation of the state, for “the beginning of the state is the most important, the most essential part, the cornerstone” of history. It should also show the distinctive properties and fate of the Russian state in comparison with the history of other states and peoples. Hence, there are two main problems in Pogodin’s study of the history of Russia: the origin of the state in Rus' and the relationship of the main points of its development with the phenomena and processes that took place in the countries of Western Europe.

Pogodin begins his historical research by finding out who the Varangian-Russ were, i.e. tribes that were the founders of the Russian state. He carefully studied the sources, primarily the chronicle, Byzantine and Western news, testimonies of Arab authors, analyzed the language, turned to religion, customs, and the actions of the first Russian princes and came to the conclusion about the Scandinavian origin of the Varangian Rus. The study of the Slavic tribes led him to the conclusion that the Slavs as a special people were known more than a thousand years before Rurik. They lived in communities, like a tribe, ruled by ancestors and elders. This explains why the newly arrived Varangians submitted to the natives and, after two or three centuries, were lost among the Slavic population, leaving traces only in the civil structure.

Addressing directly the problem of state formation, Pogodin proceeded from the fact that, like everything that exists in the world, it begins with an “inconspicuous point.” The task of the historian is “to catch it in human chaos, to trace its gradual increase, all moments, all epochs and developments, until this point, after many years, becomes filled with life, settles in its place, takes on a face, is clothed with flesh, strengthened with bones and begins to act.” In his opinion, such a point for Russia was the calling of Rurik by the Novgorodians. But this cannot yet be unconditionally called the beginning of the Russian state, Pogodin warned. The main result of Rurik's calling was the beginning of a dynasty. For Pogodin, this fact was the most important: “succession began, there was someone to follow.” The Rurik family was destined to subsequently found the greatest state in the world.

The fate of the dynasty determined the subsequent development of Russian history, and its preservation became the main concern of Russian history. Guided by Divine providence, it was “miraculously” protected from cessation. Some princes replaced others. Baby Igor connected the beginning of the story with subsequent events with a “thin thread”. He is killed, but there is Olga, Svyatoslav did not manage to stay in Bulgaria, although he wanted to. Pogodin found a connection between the death of Tsarevich Dmitry in Uglich and Peter I, declaring that “if the line of Moscow princes had not ceased, there would have been no Romanovs, there would have been no Peter.” These statements of the scientist clearly reveal his mystical idea of the historical process.

Stages of Russian history

Pogodin considered the calling of Rurik, who laid the foundation for Russian history, as its first stage and called it Norman. The Normans laid out a plan for the future state and outlined its limits. But about the state as a whole, although, as Pogodin defined, and “swept together as a living thread,” one can only speak from Yaroslav: “all tribes and cities were subject to one prince (and after one clan), were of the same origin, spoke of the same tongue... professed one faith.”

Pogodin dated the specific period from the death of Yaroslav to the Mongol invasion. Then the issue of the right of inheritance to the grand-ducal throne was in the foreground, i.e. The question is dynastic. The right of the eldest in the clan prevailed. The power of the Grand Duke was determined by his personal qualities and circumstances. The lands of Rus' were in the communal ownership of the princely family. All princes were equal to each other. However, each prince sought to isolate himself in his own inheritance and at the same time fought for the grand-ducal throne.

The next period in Pogodin’s definition is Mongolian (before the formation and establishment of the Moscow State). Then comes a new era - European-Russian, or West-Eastern, and, finally, a period of national originality. The future belongs to him. Perhaps, more definitely, Pogodin reflects the general ideas about the history of Russia not in its periodization, but in his listing of the main incidents that, according to his definition, constitute the essence of Russian history. Among them are the founding of the state, the adoption of the Christian faith, the capital Moscow, the Battle of the Don, the liberation of Russia from the Poles, the Battle of Poltava, the burning of Moscow in 1812 and “the closest to us, the most joyful, the most pressing - the liberation of twenty-five million serfs.”

Characteristics of figures of Russian history

Pogodin's main focus was on ancient and medieval history. But he also addressed events of a later time: he expressed his own view on the history of the Moscow state of the 16th century; tried to assess the events of the 17th century, the personalities of Ivan the Terrible, Peter I and others. Pogodin often entered into polemics on these issues with his predecessors and contemporaries.

The scientist characterized the personality and era of Ivan the Terrible negatively. He saw in him a weak person, an insignificant politician who lacked a state view. Pogodin considered the strengthening of power under Ivan VI as a natural state of the course of state building, which began long before him, where each subsequent prince was stronger than the previous one. He considered it an anomaly to see “progress” in the monstrous, “blind” tyranny perpetrated by the tsar. Pogodin refused to divide the life and work of Ivan the Terrible into two halves, as his predecessors did. He explained the events that took place in society, the oprichnina, and terror, not by changes in the character of Ivan IV himself, but by changes in his environment.

Pogodin wrote with respect about Boris Godunov. He rejected the allegation of his involvement in the murder of Tsarevich Dmitry, and regretted the tragic fate of Boris, who paid “for the pleasure” of learning about Dmitry’s death with “the death of his wife and beloved son, a resounding curse for two centuries.”

One of the sovereigns who admired Pogodin was Peter I. He emphasized that Peter’s reform activities and his innovations had deep roots in Russian soil. Thanks to the reforms, Russia, taking advantage of the achievements of Western civilization, “took an honorable place in the political system of European states” and acquired grounds for subsequent development.

Russia and Western Europe

The question of the relationship between the historical development of Russia and the countries of Western Europe was one of the most important in Russian historiography and socio-political thought of the 19th century. In considering it, Pogodin proceeded from two premises. First, the history of Russia is an integral part of the history of mankind, i.e. European history. The same events took place in them, due to its “general (generic) similarity” and “unity of purpose.” Therefore, a historian cannot study Russian history outside the context of European history. The second is “every people develops a special thought through its life” and thereby contributes, to one degree or another, directly or indirectly, to the fulfillment of the plans of Providence. The facts of Russian history differ significantly in their content from similar facts of the history of European peoples. Russia has always followed its own path, and it is the historian’s duty to find this path and show its originality.

All European great events, the means for the development of which “we, by Faith, language and other reasons,” did not have, were replaced with others, Pogodin wrote. We had them under a different form, solving the same problems, only in a different way. The key to understanding his use of the comparative method is in the title of the work: “Parallel of Russian history with the history of Western European states, relative to the beginning.”

There was no Western Middle Ages in Russia, but there was an Eastern Russian; an appanage system developed, which differed significantly from the feudal one, although it was a type of the same kind; the consequence of the Crusades was the weakening of feudalism and the strengthening of monarchical power, and in Russia the strengthening of monarchical power was the result of the Mongol yoke; in the West there was a reformation - in Russia - the reforms of Peter I - Pogodin finds such parallel events in Russian and Western European history. These are two processes that occur next to each other, but do not intersect. Their course is absolutely independent and independent of each other. They may go through similar stages of development, but this will not mean that they are obligatory for their evolution. Ultimately, Pogodin came to the conclusion that “the entire history of Russia, down to the smallest detail, presents a completely different spectacle.”

The scientist saw the root of the differences in the “original point”, “embryo”, i.e. addressed the already well-known thesis that the history of a people begins with the history of the state, and the source of differences lies in the characteristics of its origin. The state in Rus' began as a result of a calling, an “amicable deal.” In the West it owes its origin to conquest. The idea for Russian historiography is not new, but in Pogodin it becomes dominant, determining the fate and features of the development of Russian life in all its aspects, including institutions of power, social structure, and economic relations.

In the West, aliens defeat the natives, take away their land, and force them into slavery. The winners and the vanquished form two classes, between which an irreconcilable struggle arises. A third estate is formed in the cities. It also fights against the aristocracy. Their struggle ends in revolution. In the West, the king was hated by the natives.

In Russia, the sovereign was “an invited... peaceful guest, a welcome defender.” He had no responsibilities towards the boyars. He dealt with the people “face to face, as their defender and judge.” The land was in common possession, and the prince’s associates received it for a time as a form of salary. The people remained free. All residents differed only in their occupation, but in political and civil terms they were equal among themselves and before the prince. The upper classes acquired their privileges by “service to the fatherland, Russia.” The Russian commoner was given access to the highest government positions, “university education replaced privileges and diplomas.” We, Pogodin concluded, “have no division, no feudalism, cities of refuge, no middle class, no slavery, no hatred, no pride, no struggle.” All transformations, all innovations came from above, from the state, and not from below, as in Europe. Thus, the difference in the primary point decided the fate of Russia.

In addition to the historical reasons that divided the fates of Russia and the peoples of Western Europe, Pogodin drew attention to physical (space, soil, climate, river system) and moral (folk spirit, religion, education).

Russia occupied vast spaces, united numerous peoples, and “not mechanically, by force of arms,” but through the entire historical course of its development. This, according to Pogodin, determined such features as the attitude towards land, which for a long time had no price and because of this they did not quarrel over it; a continuous movement that took place over the course of 100 years from the death of Yaroslav to the invasion of the Mongols, which was facilitated by the rule of succession to the princely throne. The princes crossed, followed by squads, warriors, boyars, and sometimes villagers also took part in the movement. The main centers (capitals) were also moved. Pogodin saw this movement as one of the main distinguishing features of Russian history. At the same time, he emphasized, Russia never ceased to be a single whole.

Pogodin associated some features of the political development of Russia with the harsh climate, which forced “to live in houses, near hearths, among families and not care about public affairs, the affairs of the square.” The prince was given the right to independently resolve all issues. And this eliminated the basis for any “discord.” Geographical isolation associated with a system of rivers flowing into the earth, remoteness from the seas prevented communication with other peoples, which also contributed to the fact that Russia followed “its own path.”

When defining spiritual differences, Pogodin emphasized the character traits of the people - patience, humility, indifference, as opposed to Western irritability. The adoption of the Christian faith from Byzantium softened morals and contributed to the preservation of good harmony in society. The clergy in Russia was subordinate to the sovereigns. The unity of language, the unity of faith, therefore, one way of thinking of the people, Pogodin concluded, constituted the strength of the Russian state,

In determining the peculiarities of Russia's historical path and the conditions that contributed to its isolation from the Western European world, Pogodin proceeded from the traditions of Russian historiography.

He developed and clarified some of its provisions, for example, about the influence of the geographical factor on the constant movement of the population and the difficulties of relations with other peoples, about the influence of Orthodoxy on the spiritual and political life of Russian society. “How many differences are there,” he exclaimed, “in the foundation of the Russian state compared to the Western one! We don’t know which is stronger: historical, physical and moral.” Their joint action led to the fact that the history of Russia appeared “in complete contrast to the history of Western states.” The formulation and solution of the “Russia-West” problem in Pogodin’s works, with all the vulnerability of his reasoning and conclusions, attracts attention with an attempt at a holistic approach to its consideration.

History lessons

Observations of the ancient and medieval history of Russia determined by Pogodin the basic postulates of the life of Russian society. Emphasizing the historically established consensus in society, based on trust in the government and the tsar, he concluded that in this regard, “Russian history can become the most faithful and reliable guardian and guardian of public peace.” The guarantee of this has always been and is the autocracy, which cares about the welfare of the people and contributes to the preservation of historical traditions and Russian statehood. Russia has always been saved and will be saved, Pogodin argued, by autocracy, a strong state, a people who carry “in the depths of their hearts the consciousness of a united Russian land, a united Holy Rus'”; Orthodox faith, ready for all kinds of sacrifices; “a living language”, the land is spacious and fertile. On them “Holy Rus' has held, is holding and will hold!” So he comes to the well-known formula - “autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationality.”

Pogodin considered it the duty of a historian and any person to respect, cherish and work for the good of Russia. Addressing his compatriots, he wrote: “We have our own history, an amazing rich language, our own national law, our own national customs, our own poetry, our own music, our own painting, our own architecture.” To refuse this means to assert that “Russians have no history, no ancestors... There is no Rus'.” He warned about caution when trying to measure Russia by Western European standards, to look for fruits for which there are no seeds. This, however, did not mean his negative attitude towards Western Europe as a whole, its culture and science. Only transplanting “foreign plants” is not always possible or useful. It always requires “deep reflection, great prudence and caution.”

Historical science as self-knowledge of the people, Pogodin was convinced, should penetrate into their national character, help them understand themselves, what they were and, thereby, what they became. He gave history the meaning of a “teacher of life.” Pogodin was aware that each century has its own requirements and its own view of the past, and its picture changes in accordance with the state of science. And the content of Pogodin’s scientific work reflected the mood of society, its need for historical knowledge and historical science itself.

Assessing the work of Pogodin Yu.F. Samarin gave credit to the historian for trying to explain “the phenomena of Russian history from itself.” Pogodin defended the primacy of the national idea, national consciousness as the main condition for the life of Russian society. These ideas were recognized and developed in the works of other scientists, in particular, they were in tune with the mood of the Slavophiles.

He recognized the formation and development of the state as the main national idea, and in connection with this he expressed a number of provisions in the spirit of the state school. Pogodin noted the special role of the state and autocracy in Rus', representing them as national intercessors and guardians for the good of the people.

Pogodin was one of the first to draw attention to the possibility of using natural science methods in historical research. His attitude towards historical sources, his work on collecting and publishing them deserves attention. His polemic with M.T. Kachenovsky about the oldest Russian monuments had a positive meaning, Pogodin put forward a program for the development of auxiliary historical disciplines, and began work on compiling ancient Russian geography and chronicle chronology.

Pogodin was one of the historians who personified the transitional time in historical science, as K.D. wrote. Kavelin, he “all of his sides belonged to the past... but he was not alien to some new demands, views, scientific techniques that we do not find among his predecessors.”

N.G. Ustryalov (1801-1870)

Nikolai Gerasimovich Ustryalov came from the family of a serf who managed the estate of Prince I.V. Kurakina. He graduated from the Faculty of History and Philology of St. Petersburg University in 1824. Then he worked for seven years in the office of the Ministry of Finance. In 1830 he began lecturing on Russian and world history at the university “without salary.” In 1836, Ustryalov defended his dissertation for the title of Doctor of Philosophy “On the system of pragmatic Russian history.” He was elected professor and headed the department of Russian history at St. Petersburg University for almost a quarter of a century.

Ustryalov began his scientific activity with preparation for the publication of “Tales of Contemporaries about Dmitry the Pretender” and “Tales of Prince Kurbsky”. For their preparation, he was awarded two “diamond rings” and the Order of St. Anna 3rd degree. Ustryalov tried to convey interest in the source to his students; according to the recollection of one of them, he, “beginning his course with a detailed listing and evaluation of sources,” opened up to them “a completely unfamiliar world.”

A particularly fruitful period of his activity dates back to the 30-40s. In 1837, his dissertation was published, and the two-volume “Russian History” was published; in 1839-1840 “The outline of Russian history for educational institutions”; “Guide to Russian History” and others. Ustryalov received the status of an official historiographer and in 1837 was elected an adjunct of the Academy of Sciences.

Theoretical foundations of Ustryalov’s concept

“The history of the Russian state, in the sense of science, as a thorough knowledge of the past fate of our fatherland, should explain the gradual development of our civil life, from its first beginning to the latest time” - this is how Ustryalov began his first scientific work on Russian history - “On the pragmatic Russian system stories". By this he defined the main subject of historical science - the events in which the actual life of the state manifests itself: “memorable actions of people” who govern Russia’s domestic and foreign policy; successes in legislation, industry, science and the arts; religion, morals and customs. The task of the historian is “not to collect biographies,” but to present a picture of the “gradual development of social life,” “depicting the transitions of civil society from one state to another, revealing the causes and conditions of changes.” History should embrace everything, Ustryalov was convinced, that had an impact on the fate of the state. It must indicate Russia's place in the system of other states.

To solve these problems, the historian put forward two conditions: first, “the most detailed, correct and clear knowledge of the facts,” and second, bringing them into a system. Based on the tradition of criticism of historical sources, coming from A. Schletser and continued by historians of the early 19th century, he expressed his own idea of the classification of sources and the principles of their criticism. Ustryalov divided all sources into two groups - written and non-written. He included the legends of his contemporaries among the first (they are the basis of historical knowledge); acts of state, works of science and fine literature, which reflect the degree of education of the people and the spirit of their time. Ustryalov considered monuments of material culture—artistic and household items—to be “unwritten” sources.

He made a number of points about specific work with them. One cannot “unaccountably trust the facts,” he wrote; only a critical attitude to the text can give a true idea of the past. First of all, it is necessary to determine the degree of reliability of the information reported by the source. To do this, it was necessary to establish, for example, whether the author was a contemporary of the events described, whether he “passed it on to posterity as he knew.” Actual material gives the greatest completeness and accuracy to historical research. It makes it possible to find out the mechanism of government, domestic and foreign policy, economic development, and the cultural level of the country in a particular era. In the “oral traditions” Ustryalov found elements that were “obviously fabulous”, and therefore demanded a thorough check of their compliance with the “general course of events, the spirit of the times.”

Interest in sources manifested itself in his work in the Archaeographic Commission, participation in the preparation of the draft publication of the Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles. Particularly noteworthy is Uvarov’s work in collecting documents and books relating to the reign of Peter I. He received special permission to conduct research in state archives and for ten years conducted a targeted search for materials in the archives of the Naval and Military Ministries, the Senate and Synod, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs , Imperial Academy of Sciences, as well as in the archives of Vienna and Paris.

But even “the most detailed knowledge of the facts will not bring significant benefit if they are not brought into a harmonious system,” Ustryalov was convinced. He formulated the “system of pragmatic history”, widely known in his time, which provided for “an explanation of the influence of one event on another”, considering each phenomenon as “a consequence of the previous one and the cause of the subsequent one.” Such an understanding of the historical process makes it possible to identify the “thread” that connects all phenomena with an “unbreakable chain” formed by the very “course of events, the influence of the century, the genius of the people.” The historian must delve into the general meaning of history and, accordingly, determine the points where the general course of events takes on a different character, distribute all phenomena in order of importance, and “find their place” for each one. Ustryalov viewed the development of the historical process as a consequence “primarily... of the actions of people to whom fate entrusts the helm of government.” However, not always, he immediately notes: “everything that expresses the age is outlined around them in a decent perspective, that surrounds the executors of the dictates of fate and, so to speak, constitutes their sphere, from which they cannot separate and act in accordance with which.”

Ustryalov sees the importance of science and knowledge of history in the fact that history is “the true story of everything native,” “a testament of ancestors to posterity.” It, showing the true properties of the people and the needs of the state, “will serve as the best guide to the application of all kinds of statutes: for everything is multiplied by experience,” and it is “the most abundant supply of various experiences.”

The scientist’s ideas about the subject, tasks and significance of historical knowledge reflected the interest of society in the 20-30s. XIX century to civil history, history of the state, history of the people.

Ustryalov preceded his presentation of pragmatic Russian history with the reasoning of his predecessors in the field of “life-writing.” Everything done in the 18th century was, in his opinion, only “baby babble”; the approach to history was unscientific. Paying tribute to Karamzin, who “rendered the greatest service to Russian history by bringing almost all of its sources to light, selecting facts from them with rare clarity and conscientiousness, not missing a single feature, not a single remarkable word, presenting events in strict chronological order and prepared material for a pragmatic writer of everyday life,” Ustryalov disagreed with him on a number of general issues. For him, it was unacceptable that Karamzin depicted not general phenomena, “something as a whole,” but biographies of great princes and kings. Ustryalov did not see Karamzin’s historical “thread” of events either. After “strict judgments about our best writers of everyday life,” as the historian himself defined his attitude towards his predecessors, he gave an account of Russian history from a pragmatic point of view.

Periodization of Russian history

In order to find out what Rus' is, what happened to it, how the main idea developed (the formation of the state), to trace its transition from one state to another, in order to delve into the “general spirit of history,” one must begin the presentation from the “cradle” of Russian life , from the first centuries, Ustryalov believed. It is important to show the main points, the changes that have taken place, the internal and external conditions that give direction to the “fate of the state.”

Ustryalov divided the history of Russia into two main parts: ancient and modern. Each of them was divided into periods in accordance with the changes occurring in civil life. Ancient history, from the beginning of Rus' to Peter the Great (862-1689) and Modern history, from Peter to the death of Alexander I (1689-1825). The latter is distinguished by a change in the ancient way of life, the rapid development of mental and industrial forces, and the active participation of Russia in European affairs.

Ustryalov associated the emergence of civil society among the Slavs with the establishment of the supreme power of the Norman prince. At the same time, the territory of the state was formed - from the banks of Ilmen to the Dnieper rapids, from the sources of the Vistula to the banks of the Volga. The adoption of the Christian faith contributed to the merger of the diverse regions of the Russian land into one state. It became “an indispensable condition for the existence of the people, an element of Russian life”, was the basis of “a special, original direction and formed from it a separate world, different from the Western world in the main conditions of the state... in all internal institutions.” The final structure of the state took place under Yaroslav the Wise. He secured it with legislation, which determined the main conditions of civil life, i.e. a new order of succession to the throne was introduced, relations between appanage princes and the Grand Duke were established, the rights and responsibilities of the clergy were defined, and relations with neighbors were regulated. From the half of the 11th century. A struggle began between the descendants of Rurik, family disputes for supreme power. There was a division into appanages, which was a consequence of the concept of the right to an appanage for each family member. However, Ustryalov drew attention, this did not lead to the destruction of Rus', but, on the contrary, “strengthened social bonds” even more, contributed to the spread of one language, one faith, and one civil charter. The idea of autocracy remained.

The conquest of the Russian land by the Mongols and its struggle with foreign peoples in the west led to its division into eastern and western. The Mongol yoke, Ustryalov believed, did not have an impact on the internal structure of eastern Rus'. The main elements of the state remained intact - faith, language, civil life. At the beginning of the 14th century. a “great revolution” took place and the fate of Russia was determined - the gradual unification of the appanage principalities of eastern Rus' into the Moscow state began. It rose up to fight the Mongols and overthrew the yoke; got rid of the appanage system and formed “a strong, independent power - the Russian Kingdom.” Its head was an autocratic sovereign. At the same time, the western lands were united into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

After the “shocks of the Russian kingdom by impostors,” Ustryalov saw the goal of the Russian tsars in the improvement of the state, in the spirit of the most ancient charters and autocracy, which received its final education under Alexei Mikhailovich and his son Fedor.

Ustryalov began a new history with Peter the Great, who decided “everything that the Russian Tsars cared about and strived for.” He accomplished “a gigantic feat, unparalleled in history, transformed himself and his people, creating an army, a navy, industry, trade, science, art, a new and better life.” Peter assimilated the fruits of European civilization and put “his state on such a level that it suddenly became a giant among its neighbors.” The Russian kingdom was transformed into the Russian Empire. The ancient world disappeared "with most of its statutes, laws, forms, manners and customs." But despite all the changes, Ustryalov emphasized, Russia retained two main elements - religion and autocracy. The successors continued the work of Peter, and Catherine II completed it. It united almost all the Russian lands of Russia and gained “preponderance over neighboring peoples.” “Animated by the distinctive properties of the people’s character, boundless devotion to the Faith and the Throne,” Russia withstood the general shock of the Western states by the French Revolution and saved Europe from Napoleon.

Ustryalov began his contemporary period with the accession to the throne of Emperor Nicholas I. “Now, more vividly than ever,” he assessed his time, “the idea of the need for an organic structure of the state, especially on the basis of nationality and education, has awakened.”

Thus, Ustryalov, from the standpoint of the “system of pragmatic history,” presented Russian history from ancient times to his contemporary state and identified the main stages in the development of statehood in Russia. His periodization rejected the widespread division of history into ancient, middle and modern history in historiography. For him, the main thing was to trace the embodiment in the concrete life of Russia of the idea of unifying Russian lands into one state. There is no place for medieval history in Ustryalov's scheme. He did not consider this time a transitional period, since he did not see either in the reign of Ivan III or his successors the emergence of any new elements that would develop in subsequent times. From the very beginning, he emphasized, Russian history had one direction, one element in its foundation, one idea - the unification of Russian lands into one state. This process is one and undivided right up to Peter the Great, who, having changed morals, customs, and way of life, outlined a new future. Only religion and autocracy remained untouched.

Peter I

Ustryalov thus considered the Petrine era as a transitional era, and it was precisely such eras that had special significance in his system of pragmatic history. They determined the further direction of the historical process. Therefore, in his historical research, the scientist paid a lot of attention to the personality of Peter. The Tsar-Transformer, “an instrument of state change,” possessing a strong character, intelligence, and “passion,” having guessed the needs of the age, worked for Russia “with an ax in his hands,” in spite of everything. He “fought with all classes, with all concepts, prejudices... fought with all his neighbors, fought with nature, with his family, his wife, sister, son, and finally, with himself.” Peter transformed the “semi-Asian” life of Russians into a European one. For Ustryalov, it was important that Peter overcame his contempt for everything foreign, his hatred of everything new, and at the same time did not cause “harm... to the fundamental principles of the nation.” In this statement, he opposed Karamzin's views on Peter's reforms.

Peter, as Ustryalov understood him, “softened morals,” preserved and strengthened the “bright” sides of the previous era. The main ones among them were: the state-political structure of Russian life, autocratic rule “in agreement with the spirit of the people,” which respected the laws and “cared about the welfare of each class.” He presented Russian autocracy as an ideal form of government. He considered the other “bright” side of old Russian life to be the church, which preserved the faith (“quietly and calmly,” “without fanaticism and human calculations”), and “the original principles of Russian society.” For Ustryalov, Peter I is the main character, “the determinant of the future.” “We are reaping the fruits: Peter sowed.” To delve into his affairs, into his thoughts, to understand the state of the state before and after him - the scientist saw this as the task of his contemporaries.

The significance of Ustryalov’s works

Ustryalov’s “system of pragmatic history” reflected some characteristics characteristic of Russian historiography of the 20-40s. XIX century ideas, including: defining the subject of historical science - the history of the Russian state and civil life; the idea of the course of history as a continuous, progressive process determined by internal reasons; in-depth study of sources. Ustryalov proposed his own scheme of Russian history, drew attention to some little-studied problems, and gave new definitions to individual phenomena and processes. For the first time in Russian historiography, he considered the issue of dividing Rus' into Eastern and Western, and drew attention to the history of the Principality of Lithuania. From a new angle, he presented the specific system. She, in his opinion, despite the civil strife, preserved the integrity of the state, contributed to the development of trade and industry, etc. Ustryalov presented a historical overview of the reign of Nicholas I.

Little was written about Ustryalov in the 19th century, and even less in the 20th century. Soviet historiography considered his historical concept as a historical justification for the “theory of official nationality.” Indeed, he saw the foundations of Russian history in autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationality, and his works could be used for political purposes. However, this does not detract from the scientific significance of his works. Ustryalov's historical concept is the result of a deep study of the history of Russia on the basis of such principles of knowledge that in his time determined the direction of development of historical science. His historical works fit into the context of the development of historical knowledge of the 20-40s. XIX century They contributed to the formation of his contemporaries’ ideas about the history of Russia.

Literature

Durnovtsev V.I., Bachinin A.N. Pragmatic writer of everyday life: Nikolai Gerasimovich Ustryalov // Historians of Russia in the 18th - early 20th centuries. M., 1996.

Durnovtsev V.I., Bachinin A.N. Explain the phenomena of Russian life from itself: Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin // Historians of Russia of the 18th - early 20th centuries. M., 1996.

Umbrashko K.B. M.P. Pogodin: Man. Story. Publicist. M., 1999.

Introduction to the work

Relevance of the research topic

M.P. Pogodin is a prominent representative of Russian historical science of the 19th century. The relevance of studying his views is due to the fact that his historical concept is an integral part of the development of historical science, the formation of historical knowledge, it has become the most important element of domestic historiography, based on the development of which, one can most fully assess the significance and place of M.P. Pogodin as a historian. This is all the more important because Pogodin personified a transitional time in the development of Russian historical science, when, according to the historian K.D. Kavelin, history in the proper sense began to emerge from preparatory research. Pogodin “belonging to the past in all his aspects, was not alien to some new demands, views, and scientific techniques that we do not find among his predecessors.”

Pogodin was one of the first in Russian historiography to try to apply the ideas of German classical philosophy in specific historical research. Pogodin's historical concept represented one of the first attempts to substantiate the special historical path of Russia. Pogodin's historical works were a definite step forward compared to the works of his predecessors and contributed to the development of Russian historical science, expanding its source study and methodological basis.

M.P. Pogodin is known not only as a historian. He left a noticeable mark on the development of socio-political thought in Russia in the 19th century, becoming one of the ideologists of the theory of “official nationality.”

According to V.O. Klyuchevsky, “they talked about him a lot and willingly during his life, but they remember him with difficulty and indifference after his death.” Indeed, interest in his extensive scientific work wanes as he retires from the public arena. The next generation of historians (S.M. Solovyov, K.D. Kavelin, V.O. Klyuchevsky, P.N. Milyukov), who reached a new level, put the idea of historical regularity at the forefront, substantiated the need for a theoretical understanding of the past, was critical of to the works of Pogodin, who took only the first steps in this direction. Not the least role in the long-term oblivion was played by Pogodin’s belonging to the official security circles of Russia in the 19th century. Pogodin’s desire to “make Russian history the guardian and guardian of public peace” had a negative impact on the assessment of his scientific heritage. This circumstance was reflected both in pre-revolutionary historiography, and, especially, in the historiography of Soviet times.

In modern domestic historiography, there has been significant interest in studying the work of an extraordinary person, scientist, publicist, writer and public figure - M.P. Weather. This attention is largely due to the “rehabilitation” of both the conservative direction of socio-political thought in Russia in the 19th century as a whole, and individual representatives of this movement, including M.P. Pogodin, whose historical views were closely connected with the official doctrine of the first half of the 19th century - the theory of “Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality.” Modern historians strive to overcome one-sided negative ideas about the historian of the previous period, objectively evaluate his achievements, and show the contribution that Pogodin made to the development of Russian historical science.

Thus, turning to the study of the historical concept of M.P. Pogodin is dictated by the very logic of the development of historical science, which leads to the realization of the impossibility of a full-fledged and objective idea of the development of social thought in Russia, and, consequently, history itself without knowledge of the creative heritage of one of its most prominent representatives.

Object of study

The object of the dissertation research is the concept of the historical development of Russia by the Russian historian of the 19th century M.P. Weather.

Subject of study

The subject of the study includes an analysis of the general theoretical and methodological foundations of Pogodin’s historical concept, his understanding of the peculiarities of the historical development of Russia and the problem of the formation of the Old Russian state.

Chronological framework of the study

The chronological framework of the study covers the years of M.P.’s life. Pogodin (1800-1875). This time is characterized by significant changes that affected all spheres of public life, both in Russia and in Europe. Suffice it to say that M.P. Pogodin was a contemporary of such events as the Patriotic War of 1812, the uprising of December 25, 1825, the revolutions in France and Germany in 1830, 1848, the Polish uprising of 1830, the Crimean War (1853-1856), the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

In the 19th century, changes also occurred in the development of domestic historical science. Changes in historical thought were associated with the internal needs of Russian society, the shifts that took place in the public consciousness of people, and the traditions of the development of historical thought itself. Russian historical science developed in line with European science. The ideas of German classical philosophy and the ideas of leading European historical schools had a significant influence on the development of Russian historical thought.

All this was directly reflected in the historical and socio-political views of M.P. Weather.

Historiography of the problem

Literature dedicated to the life and work of M.P. Pogodin is quite extensive and is represented in various genres: scientific research covering various aspects of the historian’s work, memoirs, biographical essays. It should be noted that Pogodin’s personality itself, as well as his historical legacy, are assessed in extremely contradictory ways. This is especially characteristic of pre-revolutionary historiography.

Perhaps the most negative assessment of the personal and professional qualities of M.P. Pogodin and his entire scientific activity are presented in S.M. Solovyova.

On the other hand, in pre-revolutionary historiography there are works in which Pogodin’s personal qualities and scientific activities are extremely highly rated. In the works of the famous historian of the 19th century I.D. Belyaev, historian and publisher of monuments of Russian antiquity A.F. Bychkov, famous philologist F.I. Buslaeva Pogodin is presented as a talented teacher and historian. At their core, the works of these authors are panegyric.

In the works of historians K.N. Bestuzheva-Ryumina, P.N. Milyukova, K.D. Kavelina, M.O. Koyalovich emphasizes the special attention of M.P. Pogodin to a thorough and detailed study of the facts of Russian history. But at the same time, historians noted the reference nature of M.P.’s works. Pogodin, saw their most important shortcoming in the lack of a general picture of the historical process and system. At the same time, critics of M.P. Pogodin noted that “by speaking unfavorably about the systems and theories of Russian history, he himself, as it were, involuntarily builds them,” Pogodin had “a premonition of a complete, complete view of Russian history.”

In the works of G.V. Plekhanov and D.A. Korsakov, the socio-political views of M.P. were studied. Weather. According to

G.V. Plekhanov’s position M.P. Pogodin was closest to the Slavophile school of thought; the contradictions between them concerned only secondary issues. YES. Korsakov did not consider it possible to clearly define the direction of M.P.’s socio-political activities. Weather.