Ostrozhsky, Prince Konstantin (Vasily) Konstantinovich. Princes of Ostrog Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrog interesting facts

. Source: v. 12 (1902): Obezyaninov - Ochkin, p. 461-468 ( scan · index) Other sources: ESBE

Ostrogsky, Konstantin (Vasily) Konstantinovich, son of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich, governor of Kiev, defender of Orthodoxy in Western Rus'; born 1526, died February 13, 1608. Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich, named Vasily at baptism (he was called Konstantin after his father), remained a minor after the death of his father and was raised by his mother, the second wife of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich, Princess Alexandra Semyonovna, née Princess Slutsk. He spent his childhood and early youth in his mother's ancestral city of Turov, where, under the guidance of the most learned and experienced teachers of that time, he received a very careful education in the Orthodox Russian spirit. Having reached adulthood, Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich married the daughter of the rich and noble Galician magnate Count Tarnovsky, Sofia, and began to lead the usual lifestyle of wealthy Western Russian gentlemen. Social and government activities apparently interested him very little during this period of his life. However, even now he had to face Jesuit influence, which Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich subsequently vigorously fought until the end of his life. The Jesuits managed to invade his family life, and tried to attract to their side representatives of the influential house of the Ostrozhsky princes, so that with their help they would be more successful in promoting Catholicism among the Western Russian Orthodox population. The Jesuits managed to win over the daughter-in-law of Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich, Princess Beata, and with her help they thought of persuading her daughter Elizabeth to convert to Catholicism. Ostrozhsky stood up for his beloved niece and managed to marry her to the Orthodox Prince Dimitry Sangushko. Thanks to the intrigues of Beata and the Jesuits, Sangushko was convicted and fled to the Czech Republic, but was killed on the way, and Elizabeth was returned to Poland and forcibly married to a Pole and zealous Catholic, Count Gurka. Ostrozhsky forcibly stood up for the rights of his niece, entered into a fight with the Jesuits and Gurka, but Elizabeth, having withstood the difficult situation and persecution of the Jesuits, went crazy. Ostrogsky took her to his place in Ostrog, where the unfortunate woman lived until her death. Of course, this incident strongly armed the prince against the Jesuits and forever made him an implacable enemy of this order.

Meanwhile, very difficult times have come for the Orthodox in Western Rus'. The Russian population, which was strongly influenced by Polish civilization, already from the time of the unification of Lithuania and Poland was increasingly subject to the influence of Western European forms of Polish culture and civilization. The influence of Polish culture also affected the beliefs of the Russian population. Western Russian magnates, earlier than others, began to change the faith of their fathers and accept Catholicism; They were followed by many families from the middle class, and only the peasants firmly adhered to Orthodoxy, despite all the oppression and oppression on the part of their Catholic landowners. The rapid Catholicization of the Russian population was greatly facilitated by the Union of Lublin of 1569, which united Poland and the Lithuanian-Russian state even more closely and gave the Poles full opportunity to spread Catholicism among the Orthodox Russian population with great success. In vain did Prince Ostrozhsky with the few other Western Russian nobles who wanted to defend the political and religious independence of the Western Russian people fight against the introduction of this union: there were too few of them, and they had to come to terms with the accomplished fact. The cause of Catholicization of Russians was also greatly helped by the Jesuits, who were called to Poland to fight Protestantism penetrating from the West, but also turned against Orthodoxy. They began to penetrate the families of the most influential noble magnates and win them over to their side, gradually took over the education of youth, established their own colleges and schools, etc., and quickly, with the help of the Polish government, acquired increasing influence on the course of public life in Poland and Lithuania. The Western Russian clergy and the Orthodox population could not successfully fight this organized and unconstrained society of monks. The clergy themselves were uneducated; representatives of the highest hierarchy, who mostly came from noble and wealthy families, often looked at their rank as a profitable and profitable position, and were jealous of the luxury and splendor with which the Catholic bishops surrounded themselves. Selfishness and laxity of morals dominated among the Orthodox clergy. The mass of the Orthodox population found support among their spiritual shepherds. Catholic propaganda on such favorable soil developed widely among the Orthodox Western Russian population, capturing not only the upper Western Russian classes, but also spreading among the middle and lower classes.

Having entered the arena of public activity at such a difficult time for Orthodoxy and the Russian people, Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky, raised on Russian Orthodox principles from childhood, could not remain an indifferent witness to these events. The conditions in which he found himself could not have been more favorable to his activities. From his ancestors, in addition to his noble name, he received enormous wealth: in his possession were 25 cities, 10 towns and 670 villages, the income from which reached a colossal figure for that time of 1,200,000 zlotys per year. His outstanding position in Western Russian society, influence at court and high senatorial rank gave his personality great strength and influence. Indifferent to the affairs of the church and his people at the beginning of his activity, Ostrozhsky in the 70s began to take a closer interest in these important issues. His castle is made open to all zealots of Orthodoxy, to all those who sought intercession from Polish lords and Catholic monks. Understanding well what were the ills of contemporary Western Russian life, he, with his intelligence, easily found a way out of the difficulties in which the Western Russian Orthodox Church was placed. Ostrozhsky understood that only by developing education among the masses of the Western Russian population and raising the moral and educational level of the Orthodox clergy could some success be achieved in the fight against the organized propaganda of the Jesuits and Catholic priests. “We have grown cold towards the faith,” he says in one of his messages, “and our shepherds cannot teach us anything, cannot stand up for God’s church. There are no teachers, no preachers of God’s word.” The closest means to raising the level of spiritual education among the Western Russian population was the publication of books and the establishment of schools. These means have long been used with great success by the Jesuits for the purposes of their propaganda; Prince Ostrozhsky did not refuse these funds either. The most urgent need for the Orthodox Western Russian population was the publication of the Holy Scriptures in the Slavic language. Ostrozhsky first of all set to work on this matter. It was necessary to start with the installation of a printing house. Ostrozhsky spared neither money nor effort for this. He wrote out the font and brought to him from Lvov a famous printer who had previously worked in Moscow, Ivan Fedorov and all his employees. In order to make the publication of the Bible more efficient, Ostrozhsky copied handwritten lists of the books of the Holy Scriptures from everywhere. He obtained the main list from Moscow, from the library of Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible, through the Polish ambassador Garaburda; he obtained the Ostrog lists from other places: from the Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah, from Crete, from Serbian, Bulgarian, and Greek monasteries, he even established relations on this matter with Rome and obtained “many other bibles, various scripts and languages.” In addition, he had at his disposal the first edition of the Bible in Russian, printed in Prague, Czech Republic, by Dr. Francis Skaryna. At Ostrozhsky’s request, Patriarch Jeremiah and some other prominent church leaders sent him people “punished in the scriptures of the saints, Hellenic and Slovenian.” Using the instructions and advice of all these knowledgeable people, Ostrozhsky began to analyze all the material sent. Soon, however, the researchers were put in a difficult position, since almost all the lists sent to Ostrozhsky had errors, inaccuracies and discrepancies, as a result of which it was impossible to settle on any list, taking it as the main text. Ostrogsky decided to follow the advice of his friend, the famous Prince Andrei Kurbsky, who lived in Volyn at that time, and print the Bible “in Church Slavonic” not from the corrupted books of the Jews, but from 72 blessed and godly translators." After long and difficult work, in 1580 year, finally, the "Psalter and the New Testament" appeared with an alphabetical index to the latter, "for the sake of obtaining the most necessary things as quickly as possible." This publication, distributed in a very large number of copies, satisfied the needs of the Orthodox churches and private citizens. This edition of the Bible served as a model for Moscow edition, published much later.

But the activities of the Ostrozhsky printing house did not stop there. It was necessary to fight the Catholic influence, which was increasingly growing in Western Rus'. For this purpose, Ostrozhsky began to publish a number of books necessary, in his opinion, to raise enlightenment and fight against Latinism. From liturgical books, he published a book of hours (1598), a missal and a prayer book (1606). To combat Latinism and Catholic propaganda, he published: epistles of Patriarch Jeremiah in Vilna to all Christians, to Prince Ostrog, to Kiev Metropolitan Onesiphorus (1584), Smotrytsky’s work “The Roman New Calendar” (1587), the book of St. Basil "on the one faith", directed against the Jesuit Peter Skarga, who wrote a book about the unification of churches under the rule of the Pope (1588). “Confession of the Descent of the Holy Spirit,” an essay by Maximus the Greek (1588), a message from Patriarch Meletius (1598), and his “Dialogue against schismatics.” In 1597, the Ostrog printing house published "Apocrisis", in response to the book of the Uniates, written in defense of the correctness of the actions of the Brest Cathedral. In addition, the following books came out of Ostrog: the book of Basil the Great on fasting (1594), “Margarit” by John Chrysostom (1596), “Vershi” on the apostates, Meletius of Smotrytsky (1598). “The ABC” with a short dictionary and the Orthodox Catechism, Lavrenty Zizaniya, etc. At the end of his life, Prince Ostrozhsky allocated part of his printing house and transferred it to the Dermansky monastery that belonged to him, where the learned and intelligent priest Demyan Nalivaiko became the head of the printing business. The following were printed and published here: the Liturgical Octoechos (1603), the polemical sheet of Patriarch Meletius to Bishop Hypatius Potsey regarding the introduction of the union (1605), etc. The Derman publications were distinguished by the peculiarity that they were printed in two languages: Lithuanian-Russian and Church Slavonic, which, of course, only contributed to their greater spread among the masses of the Western Russian population. Just before his death, Ostrozhsky founded a third printing house in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, where he sent part of the font and printing supplies. This printing house, the results of which Prince Ostrogsky did not have to see, served as the basis for the later famous Kiev-Pechersk printing house, which in the 17th century was the main support of Orthodoxy in southwestern Rus'.

But when he founded printing houses and printed books in them, Ostrozhsky well understood that the matter of educating the people was far from being exhausted by this. He was aware of the need to educate the clergy, the need to create a theological school to train priests and spiritual teachers, whose ignorance and unpreparedness was clear to him. “Nothing else has caused such laziness and apostasy from the faith to multiply among people,” Ostrozhsky wrote in one of his letters, “as if from this the teachers were tired, the preachers of the word of God were tired, science was tired, they were tired of teaching, and after that came impoverishment and decline.” praise of God in His church, there has come a famine of hearing the word of God, there has come a departure from the faith and the law.” From the very beginning of his activity, Ostrozhsky began to organize schools in the cities and monasteries subordinate to him: thus, giving the land that belonged to him in Turov to Dimitri Miturich in 1572, Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich set the condition “to keep a school there.” With the material and moral support of Ostrozhsky, other schools were founded in different places in southwestern Rus'; Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich also supported fraternal schools, which played a significant role in the fight against Catholicism. But Ostrogsky’s main work at this time was the founding of the famous Academy in the city of Ostrog, from which many remarkable figures emerged in the field of Orthodoxy at the end of the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries. We do not have detailed information about the establishment and nature of this educational institution. The few data that have reached us, however, make it possible to somewhat determine, albeit in general terms, its organization. This school, which undoubtedly had the character of a higher school, was set up on the model of Western European Jesuit colleges, and the teaching in it was in the nature of preparation for the fight against Catholicism and the Jesuits. The teachers there were mainly Greeks, whom Ostrozhsky invited from Constantinople, mostly from people close to the patriarch. “And for the first time, we read in one of the modern manuscripts, I tried with the Holy Patriarch to send here didascals on the multiplication of the sciences of the Orthodox faith, but he is ready to fight for this with his fuss and does not favor their reports on this.” The first rector of the new school was the Greek scholar Cyril Loukaris, a European-educated man who later became the Patriarch of Constantinople. The school taught reading, writing, singing, Russian, Latin and Greek, dialectics, grammar and rhetoric; the most capable of those who graduated from school were sent for improvement, at the expense of Ostrozhsky, to Constantinople, to the highest patriarchal school. There was also a rich library at the school. Despite the fact that the founding of the school dates back only to 1580, in the nineties of the 16th century, an extensive scientific circle was formed from its students and teachers, grouped around Ostrog and Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich and animated by one thought - to fight Polonism and Catholicism for the Russian people and the Orthodox faith. All the most prominent figures of Western Rus' belonged to this circle: Gerasim and Melety Smotritsky, Pyotr Konashevich-Sagaidachny, priest Demyan Nalivaiko, Stefan Zizaniy, Job Boretsky and many others. The significance of this school was great. In addition to the significant moral influence on Western Russian society, in addition to the fact that the main fighters for the Orthodox Russian idea in southwestern Rus' came from it, it is important because it was the only higher Orthodox school at that time that bore on its shoulders the fight against the union and the Jesuits. propaganda. The Jesuits also understood its importance. the famous Possevin reported with alarm to Rome that the “Russian schism” was fueled by this school.

Prince Ostrozhsky also had to take direct part in the affairs of the Western Russian Orthodox Church. Seeing monasticism as one of the main means of combating Catholic propaganda, Ostrozhsky tried to raise its importance, eliminate disorder in the life of monasteries, and strengthen their moral strength and influence. In the subordinate monasteries, Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich started schools, attracted educated monks to them, and appointed learned abbots. For other Orthodox monasteries in Southwestern Rus', he printed books in his printing houses, helping them with money and “endowments.” In order to induce Western Russian monasticism to change its idle and debauched lifestyle, he published in his Ostrog printing house the book of St. Basil the Great on monasticism, introduced a new charter in the monasteries subordinate to him, from where little by little this more strict charter and corresponding to the ideals of monasticism began to pass and to other monasteries of Western Rus'.

Realizing the importance of brotherhoods in the life of the Orthodox Church, Konstantin Ostrogsky did his best to promote their prosperity. Using his influence at the Polish court and with the Patriarch of Constantinople, he easily obtained all kinds of privileges for them, provided mentors to their schools, delivered type to their printing houses, and helped them morally and financially. Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich had a particularly close relationship with the Lviv Orthodox Brotherhood, to which Ostrozhsky entrusted the upbringing of his son. The efforts of Konstantin Ostrozhsky are also known in the matter of establishing the highest hierarchy of the Western Russian church. Mainly it was necessary to change the personnel of the hierarchy, which often included vicious people. Ostrogsky, enjoying enormous influence at court, in 1592 obtained from King Sigismund III the right to patronage in the Western Russian Orthodox Church, which gave him the opportunity to independently elect worthy church shepherds who could successfully serve and help Ostrozhsky in his difficult struggle.

Meanwhile, while all these reforms were being implemented, a new danger began to threaten the Western Russian Church in the form of a union, with which Ostrozhsky also had to endure a serious struggle. Personally, Konstantin Konstantinovich at first was not even averse to union, but only on the condition that it be proclaimed by an ecumenical council, with the consent and approval of the Eastern patriarchs. Meanwhile, some bishops, led by Hypatius Potsey, thought to solve the matter at home, without asking the patriarchs, directly by agreement with the Pope. The relations that began on this occasion between Ostrozhsky and the Uniate Party did not lead to any positive results. Soon relations became so strained that, as it was clear to the Jesuits, there could be no agreement, and the Catholic party decided to pursue a union apart from Ostrogsky.

The main figures of the union - Bishops Hypatius Potsey and Kirill Terletsky - managed to win over the indecisive Kyiv Metropolitan Mikhail Ragoza to their side and obtain permission from him to convene a council in Brest in 1594 to discuss the union and related issues. Ostrogsky and the Orthodox party began to prepare for the council. Apparently, what Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich was preparing for the cathedral was too dangerous for the Uniate party, and King Sigismund III, a zealous Catholic and a great admirer of the Jesuits, at the instigation of the Catholics, banned the cathedral by decree, clearly not wanting to allow secular interference in matters churches. Meanwhile, Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich little by little had to become in very strained relations with the king and the government, which clearly patronized the Catholic tendencies of the Jesuits. Ostrozhsky began to look for allies of the Russian Orthodox party even among the Protestants, who were oppressed by the Jesuits and the reactionary Polish government no less than the Orthodox. Ostrozhsky even assumed that it would be necessary to defend his faith with arms in hand. “His Royal Majesty,” wrote Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich to the leaders of the Protestant movement, “will not want to allow an attack on us, because we ourselves may have twenty thousand armed people, and the priests can surpass us only in the number of those cooks whom the priests keep in their place.” wives." The general sympathy of the Western Russian population for Ostrozhsky and his party and hatred of Catholicism and the Jesuits grew every day, and the Jesuits decided to speed things up. Potsey and Terletsky went to Rome, were received with honor by Pope Clement VIII, and on behalf of the Western Russian hierarchs proposed submission to the Western Russian Church. Ostrogsky, having heard about this event, naturally reacted to it with indignation and issued his first message to the Russian people, in which he exhorted the Western Russian people not to succumb to the tricks of the Jesuits and papists and to oppose the introduction of the union with all their might. Ostrogsky's messages had a great influence on the population. The first to rise were the Cossacks under the command of Nalivaika and began to destroy the estates of bishops who sympathized with the union and Western Russian lords who had converted to Catholicism. The Jesuits saw that their cause, due to the resistance of Ostrozhsky and his party, could perish and decided to end it as soon as possible. A council was appointed for October 6, 1596 in Brest to finalize the issue of union. Ostrogsky immediately let the Patriarchs of Alexandria and Constantinople know about this; They sent their governors, with whom Ostrozhsky appeared on time in Brest. In Brest, however, Ostrogsky had already found supporters of the union, who, without waiting for the Orthodox party, began a council and quickly, under the leadership of the Jesuit Peter Skarga, decided on a union with Catholicism. On October 6, 1596, the Orthodox bishops also began the council, under the chairmanship of the Exarch of Constantinople, Patriarch Nicephorus and with the active participation of Ostrozhsky. The Orthodox Council sent to invite the Uniates, but they refused. Then the Orthodox bishops accused them of apostasy and pronounced excommunication over them, sending this sentence to the metropolitan who presided over the Uniate Council. Due to the intrigues of the Jesuits, the royal ambassadors, who were also present at the Uniate Council, decided to apply repression against the Orthodox and accused the patriarchal governor Nicephorus of being a Turkish spy. Both sides, of course, began to complain to the king, but Sigismund III took the side of the Uniates. Nikifor was sentenced to imprisonment, and new accusations and attacks rained down on Ostrozhsky. He was accused of not strengthening the areas entrusted to him against a possible invasion of the Tatars, and they demanded that he pay a tax, which was calculated at 40,000 kopecks. However, Ostrogsky did not dare to take drastic action against the Polish government, despite the fact that the moment was very favorable, and the Russian population, extremely excited by the union and long dissatisfied with the oppression of the Polish lords, would easily rise to defend their faith and their nationality. Prince Ostrogsky did not go further than personal explanations with the king and even restrained the Orthodox party, condemning at the same time the movement of the Nalivaika Cossacks. Sending the decree of the Polish Sejm against the Orthodox to the Lvov brotherhood in 1600, Ostrozhsky wrote to the brothers: “I am sending you a decree of the last Sejm, contrary to popular law and holy truth, and I give you no other advice than that you be patient and wait for God’s mercy, until God, in His goodness, inclined the heart of His Royal Majesty to offend no one and leave everyone to their rights.” Only in his Ostrog printing house did Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich fight against the union and Catholicism until the end of his life, printing appeals and books against Catholics and Uniates and thus supporting the Orthodox Western Russian population in the difficult struggle for their faith. Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich Ostrogsky died in old age, on February 13, 1608, and was buried in Ostrog in the Castle Epiphany Church. Of his children, only one, Prince Alexander, was Orthodox, while the other two sons, Princes Konstantin and Ivan, and daughter, Princess Anna, converted to Catholicism. Soon his printing house and school passed into the hands of Catholics, and in 1636 his granddaughter Anna Aloysia, appearing in Ostrog, ordered the prince’s bones to be removed from the tomb, washed, consecrated according to the Catholic rite and transferred to her city of Yaroslavl, where she laid them in the Catholic chapel.

Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky, despite this apparently lack of success in his activities, rendered, however, enormous services to the cause of the Russian people in Western Rus'. According to contemporaries, he was the center around which the entire Russian Orthodox party in western Rus' was grouped. With his printing house and school, he provided significant moral and cultural support to Orthodoxy in the fight against Catholicism, and with his influence and wealth he was useful to him as a major material force. Intelligent and capable by nature, Ostrozhsky understood the importance of the current moments for Western Rus' and strained all his strength to fight Western European culture, which was preparing, with the help of such an improved apparatus as the Jesuit order, to absorb the Western Russian people. Ostrogsky even abandoned his personal career: he could rarely be seen at court, and he rarely took part in campaigns, where it was easiest to advance at that time. Only in 1579, to please King Stefan Batory, he undertook a campaign against the Seversk region and this ended his military activity. Nevertheless, he directed his influence and all his strength to the defense of Orthodoxy, which largely owes him the fact that it withstood the centuries-long struggle with Catholicism and the Catholic Polish government.

Acts of Western Russia vol. III and IV; Acts of Southern and Western Russia, vols. I - II; Archiwum ksiąźąt Lubortowiczów-Sanguszków w Słowucie, t. t. I - III; Danilowicz, "Skarbiec dyplomatów" t. t. I-II (Wilno 1860-62); Archives of South-Western Russia, vol. II-VI; Monumenta confraternitatis Stauropigianae Leopoliensis, t. I, p. I-II. (Leopoli, 1895); Mukhanov's collection (according to the index); Monuments published by the temporary commission for the analysis of ancient acts, vol. IV (Kyiv 1859); Stebelski, Przydatek do Chronologjy, t. III (Wilno 1783); Kulish, "Materials for the history of the reunification of Rus'", vol. I-II; Karataev, “Description of Slavic-Russian books” vol. I (St. Petersburg, 1883); "The Life of Prince Kurbsky in Lithuania and Volyn" ed. Ivanisheva (1849); Tales of Prince Kurbsky (2nd edition, St. Petersburg, 1842); Russian Historical Library, vol. IV, VII, XIII; Scriptores rerum polonicarum, t. t. I-III; (Kraków 1872-1875); Sakharov. "Review of Slavic-Russian bibliography" (1849); Collection of monuments of the Russian people and Orthodoxy in Volyn (published by the technical and construction department of the Volyn Governorate), vol. I-II (1862 and 1872); Sopikov, “The Experience of Russian Bibliography” Part I, Nos. 69, 109, 193, 435, 464, 670, 750, 752, 987, 1, 447: “Chronicle of Grabyanka”; Batyushkov, “Ancient Monuments in the Western Provinces” (8 vols. 1868-1885, according to indexes); Stebelski, "Źywoty S. S. Eufrcizyny i Paraskiewy z genealogią, książąt Ostrogskich; Lebedintsev, "Materials for the history of the Kiev Metropolis" ("Kiev. Eparch. Vedom." for 1873); Boniecki, "Poczet rodów w Koronie i W. Ks. Litewskim XVI wieku" (Warsz. 1887); Wolff, "Kniaziowie Litewsko-Ruscy" (Warsz. 1895); Macarius, "History of the Russian Church", vol. VII, VIII and IX; Narbutt, "Dzieje narodu polskiego" t. t. IX - X; Dashkovich, "The struggle of cultures and nationalities in the Lithuanian-Russian state" ("Kiev. Univ. News" 1884, X-XII); Koyalovich, "Lithuanian Church Union" vol. I; Bantysh-Kamensky, "Historical news about the former union in Poland"; Chistovich, "History of the Western Russian Church" (St. Petersburg, 1884) part II; "Minister Magazine. The people of the Holy Spirit." 1849, IV; "Prince Konstantin (Vasily) Ostrozhsky" ("Orthodox Interlocutor" 1858, II - III); "The beginning of the union in southwestern Rus'" ("Orthodox Interlocutor" 1858, IV-X) ; Maksimovich, “Letters about the princes of Ostrog” (Kiev 1866); Kostomarov, “Russian history in the biographies of its main figures,” issue III (St. Petersburg 1874) 535-563; Perlstein, “A few words about the principality of Ostrog” (“Vremennik” Moscow. General History and Ancient." 1852, book XIV, section I); "The Kievite" 1840, book I; Elenevsky, "Konstantin II Prince of Ostrog" ("Bulletin of Western Russia" 1869, VII-IX) ; Zubritsky, “The Beginning of the Union” (“Readings Moscow. General Stories Ancient. 1848, No. 7); Batyushkov, "Volyn" St. Petersburg. 1888); A. Andriyashev, "Konstantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky, governor of Kiev" (Kiev People's Calendar" for 1881); "Proceedings of the Kiev Theological Academy" 1876, Nos. 3 and 4; 1877, No. 10, 1886, No. 1; Metropolitan Eugene, "Dictionary of writers of the ecclesiastical rank"; Vishnevsky, "History of Polish Literature" Vol. VIII; Metropolitan Eugene, "Description of the Kiev-Sophia Cathedral"; Petrov, "Essay on the history of the Orthodox school in Volyn" ("Proceedings of the Kiev Theological Academy." 1867) ; Lukyanovich, "About the Ostroh School" ("Volyn Diocesan Gazette" 1881); Kharlampovich, "Ostrozh Orthodox School" ("Kiev Antiquity" 1897, No. 5 and 6); "Kiev Antiquity" 1883, No. 11, 1885, No. 7, 1882, No. 10; Arkhangelsky, “The fight against Catholicism and Western Russian literature of the late 16th and first half of the 17th century” (1888); Seletsky, “Ostrozh printing house and its publications” (Pochaev, 1885); Maksimovich, “Historical monographs ", vol. III; "Proceedings of the Kiev Archaeological Congress", vol. II; "Ancient and New Russia" 1876, IX, 1879, III; Demyanovich, "Jesuits in Western Russia"; "Readings in the Society of Nestor the Chronicler", vol. I pp. 79-81; "Volyn Diocesan Gazette" 1875, No. 2; Solsky, "Ostrozh Bible" ("Proceedings of the Kyiv Theological Academy" 1884, VII); Levitsky, “The internal state of the Western Russian Church at the end of the 16th century and the union” (Kyiv 1881); Karamzin, (Published by Einerling) vol. X; Soloviev (published by the company "General Benefits", vols. II and III.

Ostrogsky, Prince Konstantin Ivanovich

Hetman of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, famous Western Russian figure and zealot of Orthodoxy in Lithuanian Rus'; born about 1460, died 1532. The family of the Ostrog princes belonged to the number of Russian appanage families that survived under Lithuanian rule in Western Rus' and whose members were either assistants or officials of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania. The origin of the family has not been established with precision, and of the many opinions on this issue, the most widespread and most plausible is the opinion of M. A. Maksimovich, who, on the basis of the memorial of the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery, considers it to be a branch of the Princes of Pinsk and Turov, descended from Svyatopolk II Izyaslavich , great-grandson of Vladimir the Saint. The first historically famous prince was Daniil Dmitrievich Ostrozhsky, who lived in the middle of the 14th century. His son, Fyodor Danilovich (died after 1441), canonized by the Orthodox Church under the name Theodosius and the first to lay a solid foundation for the land wealth of the family, is already a defender of the homeland and its covenants against the Poles and Latinism: over the course of several years he inflicted a whole a series of defeats and defended the independence of Podolia and Volyn to the end. The son of Prince Fyodor Danilovich, Prince Vasily Fedorovich the Red (died around 1461) continued his father’s Russian policy more successfully, but the main aspect of his activity was farming and securing his possessions from Tatar raids. Little news has been preserved about his son and the father of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich, Prince Ivan Vasilyevich. It is only known that he repeatedly fought with the Tatars and increased his holdings by purchasing new estates.

Prince Konstantin Ivanovich lost his parents early, and received his initial education under the guidance of his father’s boyars, as well as his elder brother, Mikhail. The surviving evidence of these years of Konstantin Ivanovich’s life speaks primarily of transactions for the sale and purchase of lands. Apparently, the educators of the young princes carried out only the economic plans of their deceased father. In 1486, we find the Ostrozhsky brothers in Vilna at the court of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Casimir, where they moved in the highest circle of Volyn lords - Goisky, Prince Chetvertinsky, Khrebtovich and others. At the same time, the Ostrog princes began to get accustomed to state affairs, for which they entered the then ordinary school - the retinue of the Grand Duke and accompanied him on his travels as “nobles,” i.e., courtiers. In 1491, Prince Konstantin Ivanovich already received quite important assignments and enjoyed the full confidence of the Lithuanian Grand Duke. It is very likely that by then he had already managed to emerge from among numerous Volyn princes and lords, which could have been greatly facilitated by wealth and wide family connections. However, the rise of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich was greatly influenced, of course, by his personal merits, his military talent and experience. He acquired the latter and demonstrated them in the continuous struggle with the Tatars (chronicles mention 60 battles in which he remained victorious). But there was another circumstance that contributed to the rise of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich. Already from the very accession of Grand Duke Alexander to the Lithuanian throne, a number of misfortunes befell Lithuania. The war with the Moscow Grand Duke ended in failure. The Tatars made raid after raid on the southern regions of the Lithuanian state, devastating the southern Russian lands. At this time, the Russian people especially came forward, bearing on their shoulders both the difficult struggle with the Tatars, and all the internal and external difficulties that fell on Lithuania after its unsuccessful struggle with Moscow. The Tatar raids of 1495 and 1496 were repelled exclusively by the Russians, at the head of which, thanks to his abilities, Prince Ostrozhsky soon became. The Russian princes, with the same Ostrozhsky at their head, saved the Polish king, brother of Grand Duke Alexander, from final death during his unsuccessful campaign against Moldavia. All this, of course, highlighted the importance of the Russians and the Russian Prince Ostrog, to whom all of Lithuanian Rus' had long looked with hope. Hetman of Lithuania Pyotr Yanovich Beloy, on his deathbed, directly pointed out to Alexander Konstantin Ostrozhsky as his successor. And Prince Konstantin Ivanovich was made hetman in 1497. In addition, the new hetman received a number of land grants, which immediately made him, already rich, the largest ruler in Volyn.

In 1500, a new war with Moscow began. Lithuania was not prepared for this fight: the Lithuanian Grand Duke did not have a sufficient number of troops at his disposal. Lithuania was also weakened by the raids of the Tatars, who were no longer restrained by the Grand Duke of Moscow. Despite the fact that they resorted to hiring foreigners, it was not possible to gather troops strong enough to successfully resist the Moscow forces. Prince Konstantin Ivanovich was placed at the head of the Lithuanian army. Meanwhile, Moscow troops, “like thieves,” in two detachments, invaded the Lithuanian regions. The main regiment headed for the Seversk region and, successively occupying cities, reached Novgorod-Seversky, while the second detachment, led by boyar Yuri Zakharyin, headed for Smolensk, occupying Dorogobuzh along the way. Having reinforced his army in Smolensk with a local garrison led by the energetic governor Kishka, Prince Konstantin Ivanovich moved towards Zakharyin to Dorogobuzh, deciding to delay the offensive at all costs. On July 14, the enemies met at the Vedrosha River, where the battle took place. A large Lithuanian army was completely defeated by a 40,000-strong Moscow detachment, and among many of those taken prisoner was Prince Konstantin Ivanovich. Moscow governors immediately singled out Ostrozhsky from other noble captives: he was urgently taken to Moscow, from where he was soon exiled to Vologda. Both Herberstein and Kurbsky agree on the cruel treatment of the prince, which is explained by the desire of the Moscow government to force the Lithuanian hetman to transfer to Moscow service. However, Konstantin Ivanovich did not give up, and finally decided to leave captivity, at least at the cost of breaking his oath. In 1506, through the Vologda clergy, he agreed to the proposal of the Moscow government. He was immediately given the rank of boyar, and on October 18, 1506, the usual signature of allegiance to Moscow was taken from him. Giving the latter, Konstantin Ivanovich firmly decided to flee to Lithuania, especially since the events of that time could force him to fight against his homeland. Ostrozhsky's successful fight against the Tatars in Moscow Ukraine lulled the vigilance of the Moscow government, which entrusted the new boyar with the main command over some southern border detachments. Konstantin Ivanovich took advantage of this. Under the plausible pretext of inspecting the troops entrusted to him, he left Moscow, approached the Moscow line and made his way through dense forests to his homeland in September 1507. The return of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich to Lithuania coincided with the famous Glinsky trial, so the king could not immediately begin organizing the affairs of his favorite. But in a very short time his former elderships were returned to him (Bratslav, Vinnitsa, Zvenigorod), he was given the important position in Lithuania of the elder of Lutsk and the marshal of the Volyn land, thanks to which Ostrozhsky became the main military and civil commander of all Volyn, and on November 26 he was again confirmed in the rank of hetman. In addition, Ostrogsky received a number of land grants from Sigismund, who was stingy with gifts in general. In 1508, when the war with Moscow began again, Ostrogsky was summoned from Ostrog, where he was putting property affairs in order, to Novgorod, where King Alexander was at that time, and put in charge of the army. From here he moved through Minsk to Borisov and Orsha, which was unsuccessfully besieged by Moscow governors. When Ostrozhsky approached Orsha, the Moscow army abandoned the siege and tried to delay the crossing of the Lithuanian-Polish army across the Dnieper, but all the skirmishes ended in complete failure for the Moscow governors, and the Moscow regiments, having lost energy, began to retreat. The Lithuanian army followed on the heels of the retreating enemy and finally stopped in Smolensk, from where it was first decided to send Ostrozhsky and Kishka with separate detachments to the Moscow regions, but the implementation of this plan was temporarily delayed and the favorable moment was lost. Only after some time did Prince Konstantin Ivanovich move to the city of Bely, took it, occupied Toropets and Dorogobuzh, and greatly devastated the surrounding area. This turn of events inclined both sides to negotiate peace, which resulted in the “eternal” peace of Moscow with Lithuania on October 8, 1508. Prince Konstantin Ivanovich again received several major awards. Soon after peace was concluded with Moscow, the Tatars again made a large raid, and Ostrogsky had to move against them. The Tatars were defeated near Ostrog. Now Konstantin Ivanovich began organizing his economic affairs, since during the war with Moscow he very often had to equip troops with his own money. His marriage to Princess Tatyana Semyonovna Golshanskaya also dates back to this time. A new Tatar raid forced Ostrozhsky to go to Lutsk to prepare defense, but he managed to gather only 6 thousand people, and with these small forces he managed to win a brilliant victory over a 40,000 Tatar detachment at Vishnevets, where he freed more than 16,000 people from Tatar captivity from the Russians alone . As a reward for the services of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich in the fight against Moscow and the Tatars, the king issued a general notice appointing him Pan of Vilensky, which for the prince. Ostrozhsky was very important: he entered the circle of the highest Lithuanian nobility, and from that time on he was no longer only a Volyn, but also a Lithuanian nobleman.

After the Vishnevetsky pogrom, the Tatars directed their raids into Moscow Ukraine. The Moscow government explained this behavior of its former allies by the machinations of Lithuania, and, declaring war on it again, moved a large army to Smolensk in December 1512, but after an unsuccessful siege, this army was forced to return. The second siege the following year was also unsuccessful. Finally, Smolensk was besieged for the third time and taken, the Moscow army began to move deeper into Lithuania, capturing cities along the way. Prince Ostrozhsky with the Lithuanian army went to meet him, and the first rather stubborn battle took place near the Berezina. Moscow governors were forced to retreat. At dawn on September 8, a new battle began near Orsha. With skillful maneuvers and cunning, Ostrozhsky managed to deceive the vigilance of the Russians, and the entire eighty-thousand-strong army of Moscow turned to complete flight, and the pursuit of those fleeing turned into a massacre. But Ostrozhsky still could not take Smolensk, and returned only the cities captured by Moscow. Upon returning to Lithuania, he was awarded by Sigismund an unprecedented award: on December 3, Konstantin Ivanovich was honored with a solemn triumph.

In the summer of 1516, the Tatars appeared again, causing great devastation, but as soon as rumors spread about the gathering of troops by Konstantin Ostrozhsky, the Tatars immediately left. Since June 1517, peace negotiations had been going on in Moscow, but on November 12 they were interrupted and a new war began. At the same time In time, the Tatars also attacked, in a battle with which Ostrozhsky was defeated for the first time. Lithuania's position worsened further because, in addition to Moscow and the Tatars, it had a third enemy - the Grand Master of the Livonian Order. Only the energy of King Sigismund and the talent of Ostrozhsky could stop the success of Moscow. The successful campaigns of Ostrozhsky and the tension of almost all the available forces of the country forced the Moscow government to desire peace, which was soon concluded on terms quite favorable for Lithuania and Poland. From that time on, Konstantin Ivanovich devoted himself exclusively to economic activities, which generally played a significant role in his life. He used all his free money to expand his holdings through purchases. It is clear that Ostrozhsky’s huge land holdings, together with numerous royal “nadanias,” required a lot of work and hassle to manage them. In Ostrozhsky's relations with his subjects, the prince is in the best light: he freed them from royal taxes, built churches for them, and did not give them offense to neighboring lords. Such gentleness and peacefulness earned Konstantin Ivanovich general favor and highly raised his prestige among the Orthodox Russian population. Even the subjects of other wealthy nobles fled to Ostrogsky's possessions and did not voluntarily agree to return from him to their former owners. In 1518, the grandmother of Ostrozhsky’s wife, Maria Ravenskaya, died, and her entire fortune, due to the absence of direct heirs, passed to Konstantin Ivanovich, who around this time was appointed to the rank of governor of Troksky and the first secular nobleman of Lithuania. At the beginning of July 1522, the first wife of Prince Konstantin Ivanovich, Princess Tatyana Semyonovna, née Golshanskaya, died, leaving him with an infant son, Ilya. In the same year, Ostrozhsky entered into a second marriage, from which he had a second son, the famous Vasily-Konstantin Konstantinovich. This time his choice fell on the representative of the most famous and richest Western Russian family - the Olkevich-Slutskys - Princess Alexandra Semyonovna. From that time on, he directed his public activities mainly to the benefit of the church and very rarely acted as a commander.

The rise of Prince Ostrozhsky, which was partly a consequence of the strengthening of the Russian party, could not but be accompanied by a gradual strengthening of the Orthodox element and the Orthodox Church in Lithuania, especially since Konstantin Ivanovich himself, being a faithful and devoted son of his church and always protecting the interests of Orthodoxy and the Russian people, had such friends and collaborators as the Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania Elena Ivanovna, Metropolitan Joseph Soltan and Alexander Khodkevich. A whole series of “inspirations”, petitions in favor of churches and monasteries, works in favor of the internal order of church life and its external legal position concentrated in Ostrozhsky’s personality all the interests of that time, all the sympathetic aspects of the then Orthodox society and its members. The most important changes in the church were associated with his name; favors to the Orthodox, according to the king himself, were done for the sake of Konstantin Ivanovich, who, counting on the king’s favor and his disposition towards him, was an intercessor before the government for the Orthodox Church. Thanks to his efforts, requests, petitions, The legal position of the Orthodox Church in Lithuania, which had previously been in a very uncertain position, was firmly established. With his assistance, measures were taken and partly implemented to raise the moral and spiritual level of the Orthodox masses, especially since Catholicism, which did not have zealous figures at that time, was indifferent to Orthodoxy, thanks to him the position of bishops and councilors was determined and a lot was done to organize patronage - a controversial issue between bishops and lords due to the interference of secular persons in church affairs. Konstantin Ivanovich's friendship with metropolitans, bishops and pious Orthodox lords greatly contributed to raising the material well-being of the church.

But if Konstantin Ivanovich used the main share of his influence for the benefit of the church, he still did not forget the other interests of the Russian population in Lithuania. As the bearer of the indigenous principles and historical traditions of the Russian people, Ostrozhsky became the center around which all the best Russian people of Belarus and Volyn grouped together: Prince. Vishnevetsky, Sangushki, Dubrovitsky, Mstislavsky, Dashkov, Soltan, etc. Realizing the important role of material well-being, Konstantin Ivanovich procured a lot of land from the king for the Russian people, and sometimes he himself distributed land to them.

There is very little news about Ostrogsky’s personal life. As far as one can judge the private life of Konstantin Ivanovich from the fragmentary information that has reached us, it was distinguished by amazing modesty; “light rooms” with wooden and unpainted floors, tiled stoves, windows, “clay mustaches,” sometimes “paper” and “linen, tarred” benches - that’s all the interior decoration of the house of the most powerful and richest nobleman in Lithuania. There is evidence to suggest that the private life of Prince Ostrozhsky was quite consistent with the furnishings of his home.

And the very last deed of Konstantin Ivanovich was aimed at the benefit of his native Russian people: taking advantage of the king’s favor, he asked him for the release of Lutsk, in view of the Tatar devastation, for 10 years from the payment of the ruler’s taxes and for 5 years from the payment of the Starostin taxes. It is not known exactly what participation Prince Ostrozhsky took in the drafting and publication of the Lithuanian Statute, but he joyfully welcomed this event. Prince Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky died at an advanced age and was buried in the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery, where his tomb remains to this day.

A. Yarushevich, “The Zealot of Orthodoxy, Prince Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky and Orthodox Lithuanian Rus' in his time” (Smolensk, 1897); Documents from the Ostrozhsky family archive are published under the title: "Archiwum ksiąząt Lubartowiczòw-Sanguszków w Sawucie" (Lviv, I-III, 1887-90); Niesiecki: "Herbarz Polski" (Lipsk, 1841, VII); Acts of Western Russia, vol. II-IV; Acts of southern and western Russia, vol. I-II; Archive of Southwestern Russia, vol. II-IV; Stryjkowski, Kronika, II; Stelebski: "Dwa welkie swiatha na hòryzoncie Polskiem, 1782, t. II; Karamzin (ed. Einerling), VII; Soloviev (ed. Partnership for Public Benefit), t. II; Legends of Kurbsky (2nd ed., St. Petersburg, 1842); Herberstein, "Notes on Muscovy" II; Maksimovich, Works, volume I; Proceedings of the 3rd Archaeological Congress in Kiev (abstract by Mr. Romanovsky), Kiev, 1878; Monuments, published by the temporary commission for the analysis of ancient acts, Kiev 1859, vol. IV, pp. 89-90; Kiev Diocesan Gazette, 1875, Nos. 15 and 18; Ancient and new Russia, 1879, III, 366–68; Proceedings of the Kiev Theological Academy, 1877, No. 10; Sharanevich, “On the first princes of Ostrog” (“Galician”, collection 1863, p. 226); Zubritsky, “History of the Galich-Russian principality”, Lvov, 1852, I; Koyalovich, “Readings on the history of Western history. Russia (ed. IV, St. Petersburg, 1884); Stebelski, Zywoty J. S. Eufrozyny Paraskewy z genealogią ks. O. (Vilno, 1781-83).

E. Reckless.

(Polovtsov)

. 2009 .

See what “Ostrozhsky, Prince Konstantin Ivanovich” is in other dictionaries:

Wikipedia has articles about other people with this surname, see Ostrozhsky. Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky ... Wikipedia

1460 September 11, 1530 Portrait of K. I. Ostrozhsky Place of death Turov Affiliation of the ON ... Wikipedia

Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky 1460 September 11, 1530 Portrait of K. I. Ostrozhsky Place of death Turov Affiliation of the ON ... Wikipedia

Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky 1460 September 11, 1530 Portrait of K. I. Ostrozhsky Place of death Turov Affiliation of the ON ... Wikipedia

Wikipedia has articles about other people with this surname, see Ostrozhsky. Konstantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky ... Wikipedia

Vasily Fedorovich the Red, Prince of Ostrog (? 1461) Russian prince and philanthropist of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He supported the Grand Duke of Lithuania Jogaila Casimir in his struggle for the Polish throne. Participated in the diets of 1446 and 1448 and in ... Wikipedia

Yuri Ivanovich Golshansky Prince of Dubrovitsky 1505 1536 Predecessor ... Wikipedia

Died in 1515, a descendant of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (from his son Narimund) in the 7th generation, the ancestor of the Shchenyatev princes, who died out in 1568 after the death of his grandson, the childless boyar Prince. Peter Mikhailovich. Prince Shch. was the grand-brother... ... Large biographical encyclopedia

Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky

Ostrogsky Konstantin Ivanovich (c. 1460-1530), prince, defender of Orthodoxy and the South Russian people. He was close to the courtyard. book Lithuanian, repelled the raids of the Tatars and advanced as a brave military leader. From 1498 he was Lithuanian hetman, headman of Bratslav, Vinnitsa and Zvenigorod. Ostrogsky played a particularly important role in the war. book Lithuanian Alexander with Ivan III. He acted as commander-in-chief of the Lithuanian troops and moved towards Dorogobuzh. On the river Vedroshi Ostrozhsky was defeated by Moscow troops led by Yuri Zakharyin (in 1500), captured and sent under strict supervision to Vologda. There he was persuaded by all means to transfer to Moscow service. In 1506, he agreed for the sake of appearance, gave a written note, received the rank of boyar and was appointed head of several detachments guarding the borders from Tatar raids; in 1507 Ostrogsky fled from the borderland to Lithuania. When the Tatars attacked Volyn and Galicia in 1512, he defeated them near Vishnevets. In 1512 a new war between Lithuania and Moscow began. In 1513, the Muscovites captured Smolensk, but soon suffered a strong defeat near Orsha, where the Lithuanian troops were led by Ostrozhsky. Following this, he successfully repelled the raids of the Tatars in the south, until their huge detachment of 40 thousand people. under the command of Kalga-Bogatyr did not invade Galicia. The Tatars won a victory near Sokal Castle in 1519. Ostrogsky was appointed governor by Trotsky and in 1527 completely defeated the invading Tatars on the river. Olshanitsa near Kanev.

In his concern for the Orthodox Church, he interceded for it with the government all his life, thanks to which a strong legal position was established for the Orthodox Church in Lithuania. During Ostrozhsky’s activity, the Orthodox Church received more than 20 charters that expanded and affirmed its rights. With his assistance, measures were taken and partly implemented to raise the moral level of the people, the position of bishops and councilors was determined, much was done to organize patronage and determine the limits of worldly interference in church affairs. He was buried in the Kiev Pechersk Lavra.

Materials used from the site Great Encyclopedia of the Russian People - http://www.rusinst.ru

Read further:

Ostrozhsky Konstantin Konstantinovich(1526-1608), prince, son of K. I. Ostrozhsky.

Historical figures Ukraine(biographical index).

Introduction

Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky (1460-September 11, 1530, Turov) - prince, headman of Bratslav and Vinnytsia, Vilnius castellan, governor of Troka, great hetman of Lithuania from 1497. Head of the Ostrogsky family, Orthodox.

1. Biography

At the age of 37 he became the Great Hetman of Lithuania and fought more than fifty successful battles against the Crimean Tatars.

In 1500 he lost the battle against the forces of the Grand Duchy of Moscow on the Vedrosha River, was captured and sent to Vologda. Under threat of imprisonment, he agreed to serve the Moscow Grand Duke, but in 1507 he fled, violating the oath he had given to Vasily III, approved by the guarantee of the Orthodox Metropolitan. He led the army of King Sigismund I and defeated the Moscow troops in the Battle of Orsha in 1514, innovatively combining the actions of cavalry, infantry and artillery on the battlefield.

The king granted him large plots of land for his service. Wife - Slutsk Princess Alexandra.

Patron of the arts, patron of the Orthodox Church in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, founder of the Trinity Church and Prechistensky Cathedral in Vilna, and also, possibly, St. Michael's Church in Synkovichi.

Literature

Yarushevich A. Prince Konstantin Ivanovich Ostrozhsky and Orthodox Lithuanian Rus' in his time. - Smolensk, 1897.

Bibliography:

N.M. Karamzin History of the Russian State, volume 7, chapter 6.

N.M. Karamzin History of the Russian State, volume 7, chapter 1.

Source: http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostrozhsky,_Konstantin_Ivanovich

There are two versions about the origin of the Ostrozhsky family: according to the first, they descended from the Drutsk princes, according to the second version, they were descendants of the Turov princes.

Konstantin's parents were his father Ivan Ostrozhsky and his mother Anastasia Glinskaya, and he was born approximately in 1460-1463.

In early childhood, Konstantin and his older brother Mikhail were left without a father, who died around 1466. They continued to live on their family estate Ostrog until 1481, in which year Konstantin moved to Vilna for his studies.

Two years later, Konstantin Ostrogsky returns home, but not for long, after spending a little time in Ostrog, he goes to the court of the Grand Duke for service. In 1494, he was sent with an embassy to Moscow to ask the Moscow Prince Ivan Vasilyevich to release his daughter Alena, to whom the Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander was wooing.

Having served in the princely service, Konstantin Ostrozhsky decided that this was not for him and went to Volyn, where Tatar attacks became more frequent. His military career began in 1497 with a battle near the Sarota River, where he, together with his brother Mikhail, defeated the Tatar corral. In the same 1497, Ostrozhsky participated in the campaign of Grand Duke Alexander to Moldavia and, upon returning home, defeated a thousand-strong detachment of Tatars near Ochakov under the command of the son of the Crimean Khan Makhmat-Girey. For which, in the same year, from the hands of Alexander, he received the hetman’s mace, as well as various land estates.

In 1500, the Principality of Moscow went to war against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Grand Duke Alexander sent Ostrozhsky to the border lands with a detachment of eight thousand. On the road to Dorogobuzh, on the Vedrosh River, on July 14, his detachment entered into battle with the 40 thousand army of Moscow, his detachment was completely defeated, and Ostrozhsky himself, along with other noble nobles, was captured.

Ostrogsky was put in shackles and put in prison; Prince Alexander tried through the embassy to free Ostrozhsky, but Ivan III rejected all offers. Ivan III sought from Ostrozhsky his oath of allegiance. For six years Ostrozhsky refused this to Ivan III, and remained in shackles all this time, but in 1506 he agreed to swear allegiance to Ivan III.

Ostrozhsky was released from prison and appointed to command the regiments on the southern borders, but it was not so easy for Ostrozhsky to escape to his homeland, he was watched very closely, and not in order to be captured again, he agreed to swear an oath to Ivan III, he began to wait for a convenient moment. Such a moment appeared only a year after he was released, in 1507. Konstantin Ostrozhsky, under the pretext of inspecting the regiments, left Moscow for Tula with his faithful servant. As soon as it became clear in Moscow that Ostrozhsky was heading to Lithuania instead of Tula, he was chased and almost captured; in one village Ostrozhsky stayed in a church, and his servant went further, and Moscow soldiers captured him, considering him Ostrozhsky . Through forests and swamps, Ostrozhsky was able to reach the borders of Lithuania alone and returned home. Upon returning home, from the new Grand Duke Sigismund the Old, he received back all his lands and regalia, as well as the hetman’s mace.

Not having time to stay at home for long in 1508, Ostrozhsky was again forced to go to the newly started war with Moscow, but in this war his detachment did not participate in hostilities, he only managed to occupy Dorogobuzh, abandoned by Moscow soldiers, after which there was a conflict between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Moscow a truce has been concluded.

Konstantin Ostrogsky again did not manage to visit his home in Ostrog for a long time, this time he had to go to war with the Crimean Tatars, who invaded the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The main battle in this war took place on April 28, 1512 near Vishnevets. In this battle, Konstantin Ostrozhsky completely defeated the 24 thousand Tatar corral, while his army was significantly outnumbered by the Tatar corral. After the defeat at Vishnyavets, the Tatar khan Mengli-Girey immediately sent his envoys to Sigismund to ask for peace, which was concluded a little later.

In the next war with Moscow for Smolensk, Konstantin Ostrozhsky made his name in the history of great commanders, so on October 8, 1514, in the battle of Orsha, he and his 30 thousand army defeated the 80 thousand Moscow army. This news spread throughout Europe, and the battle entered European military textbooks as an example of a strategy for fighting with fewer troops.

After the victory at Orsha, Ostrozhsky returned with his troops to Smolensk, where part of the townspeople, led by Bishop Varsanofy, was ready to surrender the city to Ostrozhsky, but he did not have time, the plot was discovered, and Varsanofy was executed. Arriving at Smolensk, Ostrozhsky realized that he did not have time, and those six thousand soldiers who remained with him after the rapid march and illnesses were clearly not enough for the assault, especially without the guns that he left to increase the speed of movement of his army.

Konstantin Ostrozhsky lifts the siege and returns back, liberating the cities of Krichev, Mstislavl and Dubrovno along the way. He travels to Vilna, where, in honor of his famous victory near Orsha, Sigismund built a triumphal arch, and through which Ostrozhsky entered the city.

After returning to Vilna, Ostrozhsky does not return home for long, and then again goes on a campaign against the city of Apochka, having stood there for some time, leaves the city, and goes to the aid of Polotsk, which was under siege, and the townspeople had almost run out of supplies. Having learned that Konstantin Ostrogsky was coming to Polotsk, Moscow troops lifted the siege and left.

After this, he returned home, where he spent the end of 1517 and the beginning of 1518, and then went to Poland, where he had the honor of meeting Sigismund’s bride Bona Sforza at the border, after which he returned to Lithuania.

After the end of the war with Moscow in 1522, Konstantin Ostrogsky became Trotsky's governor and took first place in the Rada. In the same 1522, his wife, Tatyana Galshanskaya, died, leaving Prince Ostrogsky with a son, Ivan. A year later he marries again; Alexandra Slutskaya became his wife, who bore him a daughter, Sofia, and a son, Konstantin.

In 1524, during the war with the Crimean Khanate, Konstantin Ostrogsky again went on a military campaign against Ochakov, which surrendered to Ostrogsky two days later. The next military campaign against the Tatars, in 1527, was Ostrogsky’s last. Having plundered and collected prisoners in Lithuania, the Tatars returned to Crimea, and 40 miles from Kyiv, on the Olshanka River, they decided to stop for rest. Ostrozhsky, led by his army, which amounted to about 3,500 soldiers, on January 27, 1527 at dawn, unexpectedly attacked an army of 30 thousand. Thanks to the surprise and the fact that Ostrozhsky’s horsemen were able to cut off the Tatars from their horses, victory was on the side of Konstantin Ostrogsky. He freed about 40 thousand of his compatriots from Tatar captivity.

After the victory over the Tatars, Sigismund again welcomed Ostrozhsky in Krakow with honors and gifts, and the court chronicler Decius wrote a book about the battle on Olshanka, and published it in Nuremberg in Latin. Konstantin Ostrozhsky died on August 8, 1530, and according to his will, he was buried in the Pechersky Monastery.

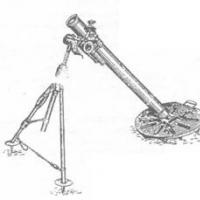

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force

US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force Differentiation of functions

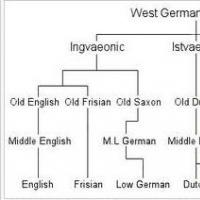

Differentiation of functions Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages

Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages Which scientist introduced the concept of valency?

Which scientist introduced the concept of valency? How does a comet grow a tail?

How does a comet grow a tail?