About whom it is said that the sphinx remains unsolved to the grave. Alexander I and the Holy Alliance

Portrait of Alexander I

Birth certificate of the newborn Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich, signed by physicians Karl Friedrich Kruse and Ivan Filippovich Beck

Ceremonial costume of seven-year-old Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich

Portrait of a Count

N.I. Saltykova

Triumphal wreath "Liberator of Europe", presented to Emperor Alexander I

The ceremonial entry of the All-Russian Sovereign Emperor Alexander I into Paris

Medal in memory of the Patriotic War of 1812, which belonged to Emperor Alexander I

Portrait of Empress Elizaveta Alekseevna in mourning

Death mask of Alexander I

The exhibition in the Neva Enfilade of the ceremonial chambers of the Winter Palace includes over a thousand exhibits closely related to the life and work of Emperor Alexander I, from the collection of the State Hermitage, museums and archives of St. Petersburg and Moscow: archival documents, portraits, memorial items; many monuments are presented for the first time.

“...The Sphinx, unsolved to the grave, They still argue about it again...” wrote P.A. almost half a century after the death of Alexander I. Vyazemsky. These words are still relevant today - 180 years after the death of the emperor.

The exhibition, which has collected a lot of material and documentary evidence, tells about the era of Alexander and allows us to trace the fate of the emperor from birth to death and burial in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. Attention is also paid to the peculiar mythology surrounding the untimely death of Alexander Pavlovich in Taganrog - the famous legend about the Siberian hermit elder Fyodor Kuzmich, under whose name the Emperor Alexander I allegedly hid.

The exhibition features portraits of Alexander I, made by Russian and European painters, sculptors and miniaturists. Among them are works by J. Doe, K.A Shevelkin and a recently acquired portrait by the largest miniaturist of the first quarter of the 19th century, A. Benner.

It is worth noting other acquisitions of the Hermitage displayed at the exhibition: “Portrait of Napoleon”, executed by the famous French miniaturist, a student of the famous J.L. David, Napoleon's court master J.-B. Izabe and "Portrait of Empress Elizaveta Alekseevna", painted from life by E. G. Bosse in 1812.

Along with unique documents and autographs of Alexander I and his immediate circle, personal belongings of the emperor are presented: the ceremonial suit of the seven-year-old Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich, the suit of a holder of the Order of the Holy Spirit, the coronation uniform (it is believed that the vest was sewn for it by the emperor himself), a cypress cross, medallion with locks of hair from Alexander I and Elizaveta Alekseevna, unpublished letters from educators of the future emperor F.Ts. Laharpe and N.I. Saltykov, educational notebooks.

Valuable exhibits were provided by collector V.V. Tsarenkov: among them is a gold-embroidered briefcase that Alexander I used during the days of the Congress of Vienna and three rare watercolors by Gavriil Sergeev “Alexandrova’s Dacha”.

The exhibition was prepared by the State Hermitage together with the State Archive of the Russian Federation (Moscow), the Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire of the Historical and Documentary Department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Moscow), the Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps (St. Petersburg), the Military Medical Museum Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation (St. Petersburg), All-Russian Museum A.S. Pushkin (St. Petersburg), State Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve "Moscow Kremlin" (Moscow), State Historical Museum (Moscow), State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg (St. Petersburg), State Museum-Reserve "Pavlovsk", State Museum-Reserve "Peterhof", State Museum-Reserve "Tsarskoe Selo", State Russian Museum (St. Petersburg), State Collection of Unique Musical Instruments (Moscow), Institute of Russian Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Pushkin House) (St. Petersburg), Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts (St. Petersburg), Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (Moscow), Russian State Military Historical Archive (Moscow), Russian State Historical Archive (St. Petersburg), Central Naval Museum (St. Petersburg), the State Museum and Exhibition Center ROSIZO, as well as collectors M.S. Glinka (St. Petersburg), A.S. Surpin (New York), V.V. Tsarenkov (London).

For the exhibition, a team of State Hermitage employees prepared an illustrated scientific catalog with a total volume of 350 pages (Slavia Publishing House). The introductory articles to the publication were written by the director of the State Hermitage M.B. Piotrovsky and Director of the State Archive of the Russian Federation S.V. Mironenko.

This is what Pyotr Andreevich Vyazemsky, one of the most insightful memoirists of the last century, called Emperor Alexander I. Indeed, the king’s inner world was tightly closed to outsiders. This was largely explained by the difficult situation in which he had been since childhood: on the one hand, his grandmother was exceptionally disposed towards him (for her he was “the joy of our heart”), on the other, a jealous father who saw him as a rival. A.E. Presnyakov aptly noted that Alexander “grew up in the atmosphere not only of Catherine’s court, free-thinking and rationalistic, but also of the Gatchina Palace, with its sympathies for Freemasonry, its German ferment, not alien to pietism”*.

Catherine herself taught her grandson to read and write, introducing him to Russian history. The empress entrusted general supervision of the education of Alexander and Constantine to General N. I. Saltykov, and among the teachers were the naturalist and traveler P. S. Pallas, the writer M. N. Muravyov (the father of the future Decembrists). The Swiss F. S. de La Harpe not only taught French, but also compiled an extensive program of humanistic education. Alexander remembered the lessons of liberalism for a long time.

The young Grand Duke showed an extraordinary intelligence, but his teachers discovered that he had a dislike for serious work and a tendency toward idleness. However, Alexander’s education ended quite early: at the age of 16, without even consulting Paul, Catherine married her grandson to the 14-year-old Princess Louise of Baden, who became Grand Duchess Elizaveta Alekseevna after converting to Orthodoxy. Laharpe left Russia. About the newlyweds, Catherine reported to her regular correspondent Grimm: “This couple is as beautiful as a clear day, they have an abyss of charm and intelligence... This is Psyche herself, united with love”**.

Alexander was a handsome young man, although shortsighted and deaf. From his marriage to Elizabeth, he had two daughters who died at an early age. Quite early, Alexander distanced himself from his wife, entering into a long-term relationship with M.A. Naryshkina, with whom he had children. The death of the emperor's beloved daughter Sophia Naryshkina in 1824 was a heavy blow for him.

* Presnyakov A. E. Decree. op. P. 236.

** Vallotton A. Alexander I. M., 1991. P. 25.

While Catherine II is alive, Alexander is forced to maneuver between the Winter Palace and Gatchina, distrusting both courts, lavishing smiles on everyone, and trusting no one. “Alexander had to live with two minds, keep two ceremonial guises, except for the third - everyday, domestic, a double device of manners, feelings and thoughts. How different this school was from La Harpe’s audience! Forced to say what others liked, he was used to hiding, what I thought myself. Secrecy has turned from a necessity into a need"*.

Having ascended the throne, Paul appointed Alexander's heir as the military governor of St. Petersburg, senator, inspector of cavalry and infantry, chief of the Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment, chairman of the military department of the Senate, but increased supervision over him and even subjected him to arrest. At the beginning of 1801, the position of Maria Feodorovna's eldest sons and herself was most uncertain. The coup of March 11 brought Alexander to the throne.

Memoirists and historians often gave a negative assessment of Alexander I, noting his duplicity, timidity, and passivity**. “The ruler is weak and crafty,” A.S. Pushkin called him. Modern researchers are more lenient towards Alexander Pavlovich. “Real life shows us something completely different - a purposeful, powerful, extremely lively nature, capable of feelings and experiences, a clear mind, perspicacious and cautious, a flexible person, capable of self-restraint, mimicry, taking into account what kind of people are in the highest echelons of Russian power have to deal with" ***.

* Klyuchevsky V. O. Course of Russian history. Part 5 // Collection. cit.: In 9 volumes. M., 1989. T. 5. P. 191.

** Alexander I was called in various ways: “Northern Talma” (as Napoleon called him), “Crowned Hamlet”, “Brilliant Meteor of the North”, etc. An interesting description of Alexander was given by the historian N. I. Ulyanov (see: Ulyanov N. Alexander I - emperor, actor, person // Rodina. 1992. No. 6-7. P. 140-147).

Alexander I was a real politician. Having ascended the throne, he conceived a series of transformations in the internal life of the state. Alexander's constitutional projects and reforms were aimed at weakening the dependence of autocratic power on the nobility, which gained enormous political power in the 18th century. Alexander immediately stopped the distribution of state peasants into private ownership, and according to the law of 1803 on free cultivators, landowners were given the right to free their serfs by mutual agreement. In the second period, the personal liberation of peasants in the Baltic states took place and peasant reform projects were developed for the whole of Russia. Alexander tried to encourage the nobles to come up with projects for the liberation of the peasants. In 1819, addressing the Livonian nobility, he declared:

“I am glad that the Livonian nobility lived up to my expectations. Your example is worthy of imitation. You acted in the spirit of the times and realized that liberal principles alone can serve as the basis for the happiness of peoples” ****. However, the nobility was not ready to accept the idea of the need to liberate the peasants for more than half a century.

Discussion of liberal reform projects began in the “intimate” circle of Alexander’s young friends when he was heir. “The Emperor's Young Confidants,” as they were called by conservative dignitaries, formed the Secret Committee for several years

*** Sakharov A. N. Alexander I (On the history of life and death) // Russian autocrats. 1801-1917. M" 1993. P. 69.

****Cit. by: Mironenko S.V. Autocracy and reforms. Political struggle in Russia at the beginning of the 19th century. M, 1989. P. 117.

(N.N. Novosiltsev, Counts V.P. Kochubey and P.A. Stroganov, Prince Adam Czartoryski). However, the results of their activities were insignificant: instead of outdated collegiums, ministries were created (1802), and the above-mentioned law on free cultivators was issued. Soon wars began with France, Turkey, and Persia, and reform plans were curtailed.

From 1807, one of the largest statesmen of Russia in the 19th century, M. M. Speransky (before the disgrace that followed in 1812), who developed a reform of the social system and public administration, became the tsar’s closest collaborator. But this project was not implemented; only the State Council was created (1810) and the ministries were transformed (1811).

In the last decade of his reign, Alexander became increasingly possessed by mysticism; he increasingly entrusted the current administrative activities to Count A. A. Arakcheev. Military settlements were created, the maintenance of which was entrusted to the very districts in which the troops settled.

A lot was done in the field of education in the first period of the reign: Dorpat, Vilna, Kazan, Kharkov universities, privileged secondary educational institutions (Demidov and Tsarskoye Selo lyceums), the Institute of Railways, and the Moscow Commercial School were opened.

After the Patriotic War of 1812, politics changed dramatically; reactionary policies were pursued by the Minister of Public Education and Spiritual Affairs, Prince A. N. Golitsyn; trustee of the Kazan educational district, who organized the defeat of Kazan University, M. L. Magnitsky; trustee of the St. Petersburg educational district D. P. Runich, who organized the destruction of the St. Petersburg University created in 1819. Archimandrite Photius began to exert great influence on the king.

Alexander I understood that he did not have the talent of a commander; he regretted that his grandmother did not send him to Rumyantsev and Suvorov for training. After Austerlitz (1805), Napoleon told the Tsar: “Military affairs is not your craft.” * Alexander arrived in the army only when a turning point occurred in the war of 1812 against Napoleon and the Russian autocrat became the arbiter of the destinies of Europe. In 1814, the Senate presented him with the title of Blessed, Magnanimous Restorer of Powers**.

Alexander I's diplomatic talent manifested itself very early. He conducted complex negotiations in Tilsit and Erfurt with Napoleon, achieved great successes at the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), and played an active role at the congresses of the Holy Alliance, created on his initiative.

The victorious wars waged by Russia led to a significant expansion of the Russian Empire. At the beginning of Alexander’s reign, the annexation of Georgia was finally formalized (September 1801) ***, in 1806 the Baku, Kuba, Derbent and other khanates were annexed, then Finland (1809), Bessarabia (1812), the Kingdom of Poland (1815) . Such commanders as M. I. Kutuzov (although Alexander could not forgive him for the defeat at Austerlitz), M. B. Barclay de Tolly, P. I. Bagration became famous in the wars. Russian generals A.P. Ermolov, M.A. Miloradovich, N.N. Raevsky, D.S. Dokhturov and others were not inferior to the famous Napoleonic marshals and generals.

*Quoted by: Fedorov V. A. Alexander I // Questions of history. 1990. No. 1. P. 63.

**See ibid. P. 64.

*** Even during the reign of Catherine II, the Kartalian-Kakheti king Irakli II, according to the Treaty of Georgievsk in 1783, recognized the patronage of Russia. At the end of 1800, his son Tsar George XII died. In January 1801, Paul I issued a manifesto on the annexation of Georgia to Russia, but the fate of the Georgian dynasty was not determined. According to the September manifesto of 1801, the Georgian dynasty was deprived of all rights to the Georgian throne. At the beginning of the 19th century. Mingrelia and Imereti recognized vassal dependence, Guria and Abkhazia were annexed. Thus, both Eastern (Kartli and Kakheti) and Western Georgia were included in the Russian Empire.

Alexander's final turn to reaction was fully determined in 1819-1820, when the revolutionary movement was reviving in Western Europe. Since 1821, lists of the most active participants in the secret society fell into the hands of the tsar, but he did not take action (“it is not for me to punish”). Alexander becomes more and more secluded, becomes gloomy, and cannot be in one place. Over the last ten years of his reign, he traveled more than 200 thousand miles, traveling around the north and south of Russia, the Urals, the Middle and Lower Volga, Finland, visiting Warsaw, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, London.

The king increasingly has to think about who will inherit the throne. Tsarevich Konstantin, rightfully considered the heir, was very reminiscent of his father in his rudeness and wild antics in his youth. He was with Suvorov during the Italian and Swiss campaigns, subsequently commanded the guard and participated in military operations. While Catherine was still alive, Constantine married the Saxe-Coburg princess Juliana Henrietta (Grand Duchess Anna Feodorovna), but the marriage was unhappy, and in 1801 Anna Feodorovna left Russia forever*.

* In connection with the actress Josephine Friedrich, Konstantin Pavlovich had a son, Pavel Alexandrov (1808-1857), who later became adjutant general, and from a connection with the singer Clara Anna Laurent (Lawrence), the illegitimate daughter of Prince Ivan Golitsyn, a son was born, Konstantin Ivanovich Konstantinov ( 1818-1871), lieutenant general, and daughter Constance, who was raised by the Golitsyn princes and married Lieutenant General Andrei Fedorovich Lishin.

After Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich’s son Alexander was born in 1818, the tsar decided to transfer the throne, bypassing Constantine, to his next brother. Summer of 1819 Alexander I warned Nicholas and his wife Alexandra Fedorovna that they would “be called to the rank of emperor in the future.” That same year, in Warsaw, where Constantine commanded the Polish army, Alexander gave him permission to divorce his wife and to have a morganatic marriage with the Polish Countess Joanna Grudzinskaya, subject to the transfer of his rights to the throne to Nicholas. On March 20, 1820, a manifesto “On the dissolution of the marriage of Grand Duke Tsarevich Konstantin Pavlovich with Grand Duchess Anna Fedorovna and on an additional resolution on the imperial family” was published. According to this decree, a member of the imperial family, when marrying a person not belonging to the ruling house, could not transfer to his children the right to inherit the throne.

On August 16, 1823, the manifesto on the transfer of the right to the throne to Nicholas was drawn up and deposited in the Assumption Cathedral, and three copies certified by Alexander I were placed in the Synod, Senate and State Council. After the death of the emperor, the package with copies had to be opened first of all. The secret of the will was known only to Alexander I, Maria Feodorovna, Prince A. N. Golitsyn, Count A. A. Arakcheev and Moscow Archbishop Filaret, who compiled the text of the manifesto.

In the last years of his life, Alexander was more lonely than ever and deeply disappointed. In 1824, he admitted to a random interlocutor: “When I think how little has yet been done within the state, this thought falls on my heart like a ten-pound weight; I get tired of it” **.

** Quoted by: Presnyakov A. E. Decree. op. P. 249.

The unexpected death of Alexander I on November 19, 1825 in distant Taganrog, in a state of moral depression, gave rise to a beautiful legend about the elder Fyodor Kuzmich - supposedly the emperor disappeared and lived under an assumed name until his death*. The news of Alexander's death opened the most acute dynastic crisis of 1825.

Alexander I was the son of Paul I and grandson of Catherine II. The Empress did not like Paul and, not seeing in him a strong ruler and a worthy successor, she gave all her unspent maternal feelings to Alexander.

Since childhood, the future Emperor Alexander I often spent time with his grandmother in the Winter Palace, but nevertheless managed to visit Gatchina, where his father lived. According to Doctor of Historical Sciences Alexander Mironenko, it was precisely this duality, stemming from the desire to please his grandmother and father, who were so different in temperament and views, that formed the contradictory character of the future emperor.

“Alexander I loved to play the violin in his youth. During this time, he corresponded with his mother Maria Fedorovna, who told him that he was too keen on playing a musical instrument and that he should prepare more for the role of an autocrat. Alexander I replied that he would rather play the violin than, like his peers, play cards. He didn’t want to reign, but at the same time he dreamed of healing all the ulcers, correcting any problems in the structure of Russia, doing everything as it should be in his dreams, and then renouncing,” Mironenko said in an interview with RT.

According to experts, Catherine II wanted to pass the throne to her beloved grandson, bypassing the legal heir. And only the sudden death of the empress in November 1796 disrupted these plans. Paul I ascended the throne. The short reign of the new emperor, who received the nickname Russian Hamlet, began, lasting only four years.

The eccentric Paul I, obsessed with drills and parades, was despised by all of Catherine’s Petersburg. Soon, a conspiracy arose among those dissatisfied with the new emperor, the result of which was a palace coup.

“It is unclear whether Alexander understood that the removal of his own father from the throne was impossible without murder. Nevertheless, Alexander agreed to this, and on the night of March 11, 1801, the conspirators entered the bedroom of Paul I and killed him. Most likely, Alexander I was ready for such an outcome. Subsequently, it became known from memoirs that Alexander Poltoratsky, one of the conspirators, quickly informed the future emperor that his father had been killed, which meant he had to accept the crown. To the surprise of Poltoratsky himself, he found Alexander awake in the middle of the night, in full uniform,” Mironenko noted.

Tsar-reformer

Having ascended the throne, Alexander I began developing progressive reforms. Discussions took place in the Secret Committee, which included close friends of the young autocrat.

“According to the first management reform, adopted in 1802, collegiums were replaced by ministries. The main difference was that in collegiums decisions are made collectively, but in ministries all responsibility rests with one minister, who now had to be chosen very carefully,” Mironenko explained.

In 1810, Alexander I created the State Council - the highest legislative body under the emperor.

“The famous painting by Repin, which depicts a ceremonial meeting of the State Council on its centenary, was painted in 1902, on the day of approval of the Secret Committee, and not in 1910,” Mironenko noted.

The State Council, as part of the transformation of the state, was developed not by Alexander I, but by Mikhail Speransky. It was he who laid the principle of separation of powers at the basis of Russian public administration.

“We should not forget that in an autocratic state this principle was difficult to implement. Formally, the first step—the creation of the State Council as a legislative advisory body—has been taken. Since 1810, any imperial decree was issued with the wording: “Having heeded the opinion of the State Council.” At the same time, Alexander I could issue laws without listening to the opinion of the State Council,” the expert explained.

Tsar Liberator

After the Patriotic War of 1812 and foreign campaigns, Alexander I, inspired by the victory over Napoleon, returned to the long-forgotten idea of reform: changing the image of government, limiting autocracy by the constitution and solving the peasant question.

- Alexander I in 1814 near Paris

- F. Kruger

The first step in solving the peasant question was the decree on free cultivators in 1803. For the first time in many centuries of serfdom, it was allowed to free the peasants, allocating them with land, albeit for a ransom. Of course, the landowners were in no hurry to free the peasants, especially with the land. As a result, very few were free. However, for the first time in the history of Russia, the authorities gave the opportunity to peasants to leave serfdom.

The second significant act of state of Alexander I was the draft constitution for Russia, which he instructed to develop a member of the Secret Committee Nikolai Novosiltsev. A longtime friend of Alexander I fulfilled this assignment. However, this was preceded by the events of March 1818, when in Warsaw, at the opening of a meeting of the Polish Council, Alexander, by decision of the Congress of Vienna, granted Poland a constitution.

“The Emperor uttered words that shocked all of Russia at that time: “Someday the beneficial constitutional principles will be extended to all the lands subject to my scepter.” This is the same as saying in the 1960s that Soviet power would no longer exist. This frightened many representatives of influential circles. As a result, Alexander never decided to adopt the constitution,” the expert noted.

Alexander I's plan to free the peasants was also not fully implemented.

“The Emperor understood that it was impossible to liberate the peasants without the participation of the state. A certain part of the peasants must be bought out by the state. One can imagine this option: the landowner went bankrupt, his estate was put up for auction and the peasants were personally liberated. However, this was not implemented. Although Alexander was an autocratic and domineering monarch, he was still within the system. The unrealized constitution was supposed to modify the system itself, but at that moment there were no forces that would support the emperor,” the historian said.

According to experts, one of the mistakes of Alexander I was his conviction that communities in which ideas for reorganizing the state were discussed should be secret.

“Away from the people, the young emperor discussed reform projects in the Secret Committee, not realizing that the already emerging Decembrist societies partly shared his ideas. As a result, neither one nor the other attempts were successful. It took another quarter of a century to understand that these reforms were not so radical,” Mironenko concluded.

The mystery of death

Alexander I died during a trip to Russia: he caught a cold in the Crimea, lay “in a fever” for several days and died in Taganrog on November 19, 1825.

The body of the late emperor was to be transported to St. Petersburg. For this purpose, the remains of Alexander I were embalmed, but the procedure was unsuccessful: the complexion and appearance of the sovereign changed. In St. Petersburg, during the people's farewell, Nicholas I ordered the coffin to be closed. It was this incident that gave rise to ongoing debate about the death of the king and aroused suspicions that “the body was replaced.”

- Wikimedia Commons

The most popular version is associated with the name of Elder Fyodor Kuzmich. The elder appeared in 1836 in the Perm province, and then ended up in Siberia. In recent years he lived in Tomsk, in the house of the merchant Khromov, where he died in 1864. Fyodor Kuzmich himself never told anything about himself. However, Khromov assured that the elder was Alexander I, who had secretly left the world. Thus, a legend arose that Alexander I, tormented by remorse over the murder of his father, faked his own death and went to wander around Russia.

Subsequently, historians tried to debunk this legend. Having studied the surviving notes of Fyodor Kuzmich, researchers came to the conclusion that there is nothing in common in the handwriting of Alexander I and the elder. Moreover, Fyodor Kuzmich wrote with errors. However, lovers of historical mysteries believe that the end has not been set in this matter. They are convinced that until a genetic examination of the elder’s remains has been carried out, it is impossible to make an unambiguous conclusion about who Fyodor Kuzmich really was.

Bakharev Dmitry

A history teacher

Shadrinsk 2009

Introduction

I was briefly faced with the question of the topic of the essay - thanks to my passion for alternative history and the secrets of the past, I chose a topic from the group “Secrets and mysteries of Russian history.”

Russian history is extremely rich in such things as secrets and riddles. Figuratively speaking, the number of “white spots and underwater reefs” is very large. In addition, the wide variety of these “blank spots” indicates the imagination of our ancestors, who left such an “interesting” legacy to their descendants.

Among all these mysterious events, cases of imposture stand out as a separate group. Here it must be said that imposture is one of the most popular ways of “self-expression” in Rus'. Well, why shouldn’t Grishka Otrepiev remain Grishka Otrepiev, and Emelyan Pugachev Emelyan Pugachev? But no! This is how Russia recognized False Dmitry I and the self-proclaimed Peter III. Perhaps, without them, the fate of our Fatherland would have turned out completely differently.

The number of cases of imposture in Russia is not just high, but enormous. This “folk pastime” was especially popular during the Time of Troubles. False Dmitry I (Grigory Otrepyev), son of Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich Peter, who did not exist in reality (Ilya Gorchakov), False Dmitry II, a cloud of self-proclaimed princes: Augustus, Lavrenty, Osinovik, Clementy, Savely, Tsarevich Ivan Dmitrievich (Yan Luba) - the names can go on for a long time list. Even in the 20th century, imposture did not become obsolete, although even here it was not without the royal family: a breakthrough of “the miraculously saved children of Nicholas II,” and even the “emperor” himself; only later did the “grandsons of Nicholas II” appear, in particular Nikolai Dalsky, allegedly the son of Tsarevich Alexei. In 1997, crowned Nicholas III; Alexey Brumel, who proposed to crown either Yeltsin or Solzhenitsyn, and then declared himself tsar - and these are only the most famous, and how many cases of local significance! Suffice it to recall the works of Ilf and Petrov about the children of Lieutenant Schmidt.

But we are particularly interested in the earlier period. The beginning of the 19th century, the era of Alexander I. The mysterious death of Alexander. The unexpectedness and transience of his death, his strange hints the day before, the metamorphoses that occurred with the body of the late sovereign, the unprecedented security measures for the funeral and their extraordinary secrecy - all this caused rumors, gossip, and after the appearance in Siberia of a strange old man, in whom one soldier recognized the tsar , - and excitement. And what does the dying confession of the old man mean, that he is the late king - father? Perhaps the vain old man wanted worship before death and a royal funeral. Or perhaps the former emperor did not want to give his soul to God under someone else’s name. All this is fraught with an insoluble mystery that is unlikely to ever be solved, but I do not set myself any supernatural tasks - the purpose of this work is only to illuminate this mysterious event, consider all existing ones, reason about each of them and present them to your judgment .

It must be said that not all of the work is devoted specifically to the mystery of death.

Alexandra. The first two chapters tell about the youth, life and reign of the emperor, and only the third chapter talks directly about the mysterious death of the emperor. In conclusion, conclusions for each version are submitted for your judgment. I hope that my work will not disappoint you.

Chapter I. The Alexandrov Days are a wonderful beginning...

Alexander I, the eldest son of Paul I from his second marriage to Maria Fedorovna, was born in St. Petersburg. His upbringing was carried out by Empress Catherine herself, who took from her parents both the first-born Alexander and his young brother Constantine. She literally idolized young Alexander, she herself taught him to write and count. Catherine, wanting to develop the best inclinations in her children, personally compiled the “ABC”, where the teachers of her grandchildren were given clear instructions on education, based on the principles of “natural rationality, healthy living and freedom of the human person.”

In 1784, a general devoted to the empress was appointed chief educator. In addition to him, the young grand dukes have a whole staff of mentors and teachers. Among them: the scientist geographer Pallas, a professor - archpriest, a popular writer. Alexander is greatly influenced by another person - Friedrich Laharpe, a Swiss politician and a staunch liberal, a man called upon to give legal knowledge to the future king. He instilled in Alexander sympathy for the republican system and disgust for serfdom. Together with his teacher, the Grand Duke dreamed of the abolition of serfdom and autocracy. Thus, liberal views were instilled in Alexander from a young age. However, education based on humane principles was divorced from human reality, which significantly influenced the character of the heir: impressionability and abstract liberalism on the one hand, inconsistency and disappointment in people on the other.

But even though Alexander had a sharp and extraordinary mind by nature, as well as an excellent selection of teachers, he received a good, but incomplete education. Classes stopped simultaneously with the marriage of the future emperor to the Baden princess Louise (in Orthodoxy Elizaveta Alekseevna).

It cannot be said that his family life was successful. As bride and groom, the future spouses loved each other, but after the wedding the young Grand Duchess became interested in a more courageous man - Prince Adam Czartoryski. When, much later, she gave birth to a girl who looked remarkably like the handsome prince, Czartoryski was immediately sent as ambassador to Italy.

From an early age, Alexander had to balance between his father and grandmother who hated each other, which taught him to “live on two minds, keep two ceremonial faces” (Klyuchevsky). This developed in him such qualities as secrecy, duplicity and hypocrisy. It often happened that, having attended the parade in Gatchina in the morning, where everything was saturated with parade mania and drill, in the evening he went to a reception in the Hermitage, luxurious and brilliant. Wanting to maintain good relations with both his grandmother and his father, he appeared before each in a suitable guise: before the grandmother - loving, before his father - sympathetic.

Catherine cherished the idea of transferring the throne directly to Alexander, bypassing his father. Knowing about this desire of hers and wanting to spoil relations with his father, Alexander publicly declared that he did not want to reign and preferred to go abroad “as a private person, placing his happiness in the company of friends and in the study of nature.” But Catherine’s plans were not destined to take place - after her death, the country was headed by Emperor Paul I.

Having become emperor, Paul did not exile and put his son into disgrace, as many might have thought. Alexander was appointed military governor of St. Petersburg, chief of the Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment, inspector of cavalry and infantry, and later chairman of the military department of the Senate. Fear of a tough and demanding father completed the formation of his character traits.

A few months before the tragic night of 11 March 12 Vice-Chancellor Panin let Alexander know that a group of conspirators, including himself, intended to overthrow Paul from the throne, due to his inability to rule the country, and put Alexander in his place. Perhaps the Tsarevich would have stopped the coup attempt if Paul, like his mother, had not made Alexander understand that he did not intend to leave him the crown. Moreover, recently Paul has brought his wife’s nephew, the Prince of Württemberg, closer to him. He called a young man from Germany, planned to marry him to his beloved daughter Catherine, and even gave him hope of becoming an heir. Alexander, seeing all this, agreed to the coup, although without planning for his father’s death.

When, on the ill-fated night of March 11-12, he was informed that Emperor Paul was dead, he experienced severe shock and shock. Maria Fedorovna, Pavel's wife and Alexander's mother, added fuel to the fire. Having fallen into hysterics, she accused her son of killing his father, branding him a “parricide.” The conspirators barely managed to convince him to go out to the guards and say that Paul had died of an appoplectic stroke, and that the new emperor, he, Alexander, would rule “by law and according to his heart in the god of our late august grandmother.”

In the first months of the reign of the new emperor, it was not he who ruled in St. Petersburg, but the count, who considered himself the patron of the young sovereign. And, given Alexander’s completely depressed and depressed state, it was not at all difficult. But Alexander had neither the strength nor the will to fight the dictates of Palen. One day he complained to a member of the Senate, General Balashov, about his condition. The general, a straightforward and fair man, said to Alexander: “When flies buzz around my nose, I drive them away.” Soon the emperor signed a decree dismissing Palen; in addition, he ordered him to leave for his Baltic estate within 24 hours. The young sovereign understood perfectly well that people, having betrayed him once, would betray him again. So, gradually all the participants in the conspiracy were sent on a trip to Europe, exiled to their own estates, and attached to military units either in the Caucasus or Siberia.

Having removed all the conspirators, Alexander brought close friends to himself: Count Pavel Stroganov, Prince Victor Kochubey, Prince Adam Czartoryski, Count Nikolai Novosiltsev. Together with the emperor, the young people formed a “secret committee”, called by Alexander the “Committee of Public Safety”. At its meetings they discussed the transformations and reforms necessary for Russia. First of all, all the innovations of Paul I were canceled: charters granted to the nobility and cities were restored, amnesty disgraced nobles who fled abroad, more than 12 thousand people exiled or imprisoned under Paul were released, the Secret Chancellery and the Secret Expedition were disbanded, clothing restrictions were abolished, and much more. Public education in Russia also received a powerful impetus: the Ministry of Public Education was created for the first time, and schools and gymnasiums were opened throughout the country. Two higher educational institutions were opened: the Pedagogical Institute and the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. Among his first graduates were his comrades.

The least was done for the most humiliated - the serfs. Although a decree was issued on free cultivators, the liberation of peasants according to it took place on such enslaving conditions that during the entire reign of Alexander, less than 0.5% of the total number of serfs were freed on his terms.

On behalf of the emperor, Speransky prepared many more good projects to transform Russia, but all of them remained idle. Even rumors that Speransky was preparing a project to abolish serfdom caused furious indignation among the nobles. Having met resistance once, Alexander no longer dared to carry out any reforms. Moreover, under pressure from society, he was forced to expel Speransky, an outstanding manager who was worth the entire “secret committee” combined. In addition, Speransky was suspected of secret sympathy for France, which on the eve of the war with her further increased hatred of him.

Chapter II. This is a true Byzantine...subtle, feigned, cunning.

Already at the beginning of Alexander's reign, one could assume a high probability of war with France. If Paul, before his death, broke off all relations with England and entered into an alliance with Bonaparte, then Alexander first of all resumed trade relations with England, and then concluded an agreement on mutual friendship, directed against Bonaparte. And soon, after Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor of France, Russia joined the third anti-French coalition. Its allies were Austria, Sweden and England.

During the war, Alexander, for the first time among Russian sovereigns after Peter I, went to his army and observed the battle from afar. After the battle, he drove around the field where the wounded, his own and others, lay. He was so shocked by human suffering that he fell ill. He ordered help to all the wounded.

The culmination of the war of the third coalition against Napoleon was the Battle of Austerlitz. It was after him that the emperor disliked Kutuzov. Alexander, dissatisfied with the slow development of the battle, asked Kutuzov:

Mikhail Larionich, why don’t you go forward?

“I’m waiting for all the troops to gather,” answered Kutuzov.

After all, we are not in Tsarina’s Meadow, where they don’t start the parade until all the regiments arrive,” Alexander said dissatisfied.

“Sir, that’s why I’m not starting, because we’re not in Tsaritsyn’s meadow,” answered Kutuzov.

Kutuzov did not dare to adequately continue the dialogue with the Tsar and led his column into battle from an advantageous height. Napoleon immediately took it. The battle ended with the complete defeat of the Russian-Austrian troops.

After the battle, Alexander was completely out of control. The convoy and his retinue lost him. The horse, disobedient to a weak rider like Alexander, could not jump over the ditch that was in the way. It was then that, having nevertheless overcome a trivial obstacle, the 28-year-old emperor sat down under a tree and burst into tears...

Alexander's actions become completely unpredictable. Suddenly, to the post of Commander-in-Chief, he appoints a man absolutely unsuitable for this position - a 69-year-old field marshal. The army remains in Europe with the new commander-in-chief and immediately suffers a terrible defeat at Preussisch-Eylau. The future Minister of War, General Barclay de Tolly, was wounded there. He was treated for his wounds in the city of Memel. In a conversation with the emperor, the general spoke for the first time about the tactics of Russia's future war with Napoleon. In those years no one doubted that it would happen. At the bedside of the wounded Barclay de Tolly, Alexander heard bitter truths for the first time. There is no commander in Russia capable of resisting the military genius of Napoleon. And that the Russian army, apparently, will have to use the ancient tactics of luring the enemy deep into the country, which the general did successfully until he was replaced by Kutuzov. But he also continued what his predecessor had started.

In 1807, the Peace of Tilsit was concluded between France and Russia. It was signed personally by the two emperors, who met privately on a floating pavilion in the middle of the Neman River. They conditionally divided the zones of influence of each of them: Napoleon rules in the West, Alexander - not in the East. Bonaparte directly indicated that Russia should strengthen itself at the expense of Turkey and Sweden, while Italy and Germany would not be given to him, Napoleon.

His goals were quite obvious: to drag a potential enemy into two long, protracted wars at once and weaken him as much as possible. But it must be said that the Russian troops dealt with both rivals quite quickly, annexing Finland and the lands beyond the Danube.

Dissatisfaction with the Peace of Tilsit among people was growing. They did not understand how their emperor could be friends with this “fiend of the revolution.” The continental blockade of England, adopted by Alexander under Tilsit, caused significant damage to trade, the treasury was empty, and the banknotes issued by it were completely worthless. The Russian people were irritated by the appearance of the French embassy in St. Petersburg after Tilsit, its arrogant and self-confident behavior, and its great influence on Alexander. Alexander himself could not help but see that his policy did not find understanding and support among his subjects. The Peace of Tilsit increasingly disappointed him: Napoleon openly did not comply with the terms of the treaty and was not interested in Alexander’s opinion. This unceremonious behavior terribly irritated the Russian emperor. Gradually he began to prepare for war.

On the night from 11 to 12 June In 1812, the emperor learned about the beginning of the war. During the ball, he was informed about Napoleonic crossing of the Neman, but the tsar continued to dance. Only after the ball did he announce the start of the war and leave for Vilna, to join the army.

Alexander sent a letter to the State Council of St. Petersburg with the following content: “I will not lay down my arms until not a single enemy warrior remains in my kingdom.”

He ended his address to the army with the words: “God is for the beginner.” He remembered this phrase from Catherine’s “ABC”, written by her with her own hand for her grandchildren. At first, Alexander himself was eager to lead, but soon became convinced of his inability to command troops and left the army in early July. Saying goodbye to Barclay de Tolly (this was in the stable where the general was cleaning his horse), Alexander said: “I entrust you with my army, do not forget that I do not have a second one - this thought should not leave you.”

The Emperor arrived in Moscow July 11. Here he was literally shocked by the patriotic impulse of the people. So many people had gathered that he could barely make his way through the crowd. He heard the shouts of Muscovites: “Lead us, our father!”, “We will die or we will win!”, “We will defeat the adversary!” The moved emperor forbade the soldiers to disperse the crowd, saying: “Don't touch them, don't touch them! I'll pass! In Moscow, Alexander signed the Manifesto on a general militia, which a huge number of people joined.

Excitement and dissatisfaction with the retreat of the Russian troops grew more and more. Under pressure from public opinion, Alexander appointed infantry general Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov, whom he disliked but was beloved by the people, to the post of commander-in-chief. He immediately stated that Barclay de Tolly adhered to the correct tactics, and that he himself intended to follow them. Later, to please the Kutuzov society, the French fought the battle of Borodino. After him, Napoleon will say: “The most terrible of all my battles is the one I fought near Moscow. The French showed themselves worthy of victory, and the Russians acquired the right to be invincible.”

Despite the tsar’s demand for a new battle, Kutuzov, who had received the highest military rank of field marshal the day before, decided to surrender Moscow without a fight in order to preserve the army. This was the only correct solution for Russia.

The emperor had a lot of worries after the Battle of Borodino, the retreat and the fire of Moscow. Even after turning gray overnight, his intention not to yield to Napoleon remained unchanged. Napoleon, who had already begun to doubt the success of his campaign in Russia, tried to negotiate from busy Moscow, but Alexander remained silent.

Recent events, experiences and anxieties have changed Alexander enormously. Later he would say: “The fire of Moscow illuminated my soul.” The emperor began to think more often about life, sincerely believed in God, and turned to the Bible. His traits such as pride and ambition receded. So, for example, when the army wanted the emperor himself to become commander-in-chief, he categorically refused. “Let those who are more worthy of them reap the laurels than me,” said Alexander.

At the end of December 1812, Field Marshal Kutuzov reported to the Tsar: “Sovereign, the war ended with the complete extermination of the enemy.”

After the expulsion of Napoleon from Russia, the emperor insisted on continuing the war, although Kutuzov told him about the deplorable state of the army, and about the fulfillment of the vow “until not a single enemy warrior remains in my kingdom,” which was fulfilled, to which Alexander replied: “If you want a lasting and reliable peace, it must be concluded in Paris.”

The final stage of the Russian army's overseas campaign, the Battle of the Nations, ended with the victory of the anti-French coalition forces led by Russia. On the third day of the battles, Alexander personally commanded the troops from the “royal” hill, where the Prussian emperor and the Austrian king were with him.

Finally, the Allied troops occupy Paris. The Parisians rejoice when they realize that Alexander is not going to do to Paris the same as he did to Moscow. This is a triumph of Russian weapons and Russia! Russia did not know such success and influence even under Catherine. Alexander is the initiator of the Congress of Vienna and the Holy Alliance of Emperors. He insists on introducing a constitution in France, and at his request it also appears in Poland. It’s a paradox – an autocratic sovereign introduces constitutional law in foreign states. He also instructs his closest officials to carry out a similar project for Russia. But gradually, over time, Alexander’s ardor fades away. He is moving further and further away from government affairs. Towards the end of his reign, the emperor increasingly falls into melancholy, he is overwhelmed by apathy and disappointment in life. The gravity of his father's murder has weighed on him all his life, but now it manifests itself especially strongly. “The crowned Hamlet, who was haunted all his life by the shadow of his murdered father,” as they said about him. Right now he especially fits this description. He perceives any misfortune as God's punishment for his sins. He considers the death of two daughters from Elizaveta Alekseevna and a daughter from a relationship with Naryshkina a punishment for his sins. The worst flood in history in St. Petersburg had a particularly strong impact on him, November 19 1824, which served apotheosis all the misfortunes. Most likely, it was then that his decision to leave the throne finally matured, as he assured his loved ones. His statement is known that “he has already served 25 years, a soldier is given retirement during this period.”

Alexander becomes a religious and pious person. At the same time, Masonic lodges are multiplying throughout the country. This infection is spreading at truly enormous speed. When one of the officials remarked to the emperor that they should be banned, Alexander only quietly replied: “It’s not for me to judge them,” but nevertheless, before his death, he issued a rescript banning Masonic lodges.

September 1 The emperor leaves for Taganrog. This departure was quiet and unnoticed, allegedly necessary in order to improve the empress’s health. But first, Alexander stops by at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, where they hold not a prayer service for him, but a memorial service! Then the emperor quickly leaves for Taganrog. There they live with the empress quietly and peacefully, not interested in business. Alexander makes several trips to nearby cities and suddenly falls ill. It is not known for certain whether it was malaria or typhoid fever. The doctors know how to treat him, but Alexander forbade them even to approach him.

Chapter III. "The Sphinx, not solved to the grave"

Disputes about the mysterious death of Alexander still continue. Or maybe not death at all? Let's consider all the oddities, one way or another, related to the circumstances of the death of the sovereign.

The first and most obvious is Alexander himself, who tirelessly repeated that he intended to leave the throne, that the crown had become too heavy, and the day was not far off when he would abdicate the throne and live as a private citizen.

The second oddity is the mysterious departure and visit to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. His departure took place under extremely interesting circumstances. The tsar set out on the long journey completely alone, without an entourage. At five o'clock in the morning, long after midnight, the emperor's carriage drives up to the monastery, where he is met (!) by Metropolitan Seraphim, the archimandrite and the brethren. The emperor orders the gates to be closed behind him and no one allowed into the service. Having received blessing from the metropolitan, he, accompanied by the monks, goes inside the cathedral. Further opinions differ: according to one version, the usual prayer service was served, which Alexander always served before any long trip; according to another version, a memorial service was served for Alexander that night. At first this is unlikely, but why then was it necessary to come to the Lavra alone, so late, and order the gates to be closed? All this indicates that something unusual was happening in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra that night. Leaving the Lavra, Alexander, with tears in his eyes, said goodbye to the brethren: “Pray for me and for my wife.”

Even the disease from which the emperor supposedly died is another mystery. According to information that has reached us, this is either malaria or typhoid fever. The sovereign’s illness itself is also a complete surprise. No longer young, but not old either, the strong emperor was suddenly felled by an illness unknown to us. One thing is certain - the doctors know how to treat him, but Alexander forbids his relatives to allow him to see a doctor, which leads to an obvious result: on November 19, the emperor died. The next day, the king’s relatives and doctors were quite surprised: Alexander’s body, despite the recent date of death, was swollen, loose, emitted an unpleasant odor, his face turned black, and his facial features changed. Everything was attributed to the local air and climate. And a few days ago, courier Maskov, who looked extremely like the emperor, died in Taganrog, and his body mysteriously disappeared. His family still maintains a legend that it was the courier Maskov who was buried in Petropavlovskaya fortresses instead of the emperor. There are several other oddities that cast doubt on the actual death of the emperor. Firstly, Alexander, an extremely pious man, could not help but confess before his death, but nevertheless, he did not do this, and even his relatives who were present there did not call a confessor, which indicates their dedication to the king’s (possible) plan. Secondly, subsequently it was not possible to find any documents related directly to the death of the emperor. And, thirdly, a memorial service was never served for the deceased Alexander.

The body of the late king was placed in two coffins: first in a wooden one, then in

lead. This is what Prince Volkonsky, who was responsible for transporting the body of the deceased to St. Petersburg, reported to the capital: “Even though the body is embalmed, but from the local damp air the face turned black, and even the facial features of the deceased completely changed...

Therefore, I think that the coffin should not be opened.”

The body of the deceased emperor was transported to Moscow in the strictest secrecy, but despite this, rumors ran far ahead. There were all sorts of rumors about the deceased sovereign: That he was sold into foreign captivity, that he was kidnapped by treacherous enemies, that his closest associates killed him, and that, finally, he abdicated the throne in such an unusual way, that is, he fled, relieving himself of the burden of power . There were rumors that some sexton managed to spy who was being carried in a coffin. When he was asked if it was really the Tsar-Father who was being transported, he replied: “There is no sovereign there, it is not the sovereign who is being transported, but the devil.”

Upon arrival in Moscow, the coffin with the body was placed in the Archangel Cathedral of the Kremlin, where the coffin, contrary to Volkonsky’s advice, was opened, but only the closest people said goodbye to the late sovereign. Some hotheads expressed the opinion that it would be necessary to verify the authenticity of the deceased, and perhaps they would have succeeded if not for the unprecedented security measures: the introduction of a curfew, enhanced patrols.

Alexander was buried March 13 In Petersburg. But…

...another version of events is also possible. Then all the oddities turn into completely natural actions. It becomes clear that Alexander’s funeral service during his lifetime in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, and the excessive swelling and decomposition of the body - after all, courier Maskov died before Alexander. And we don’t even have to talk about the loss of documents, the “false” illness and the absence of a confessor. In addition, it is obvious that many of the emperor’s relatives were privy to his plan - how else can one explain the fact that no one ever ordered a memorial service for the deceased king.

Ten years have passed.

A strong, broad-shouldered elderly man drove up to a blacksmith shop in Krasnoufimsk, Perm province, and asked to shoe a horse. In a conversation with the blacksmith, he said that his name was Fyodor Kuzmich, he was traveling without any official need, just “to see people and the world.” The blacksmith became wary and reported the free wanderer to the police. The policeman asked the old man for documents, which he did not have. For vagrancy, Fyodor Kuzmich was sentenced to twenty lashes and exile to Siberia. He, along with the rest of the exiles, was sent along a convoy to the Krasnorechensky distillery, where they were assigned to settle. After living there for five years, Fyodor Kuzmich moved to the village of Zertsaly. He built himself a hut-cell outside the village, where he lived for many years.

The elder taught peasant children to read and write, history, geography, and the Holy Scriptures. He surprised adults with stories about the Patriotic War, military campaigns and battles. He knew court etiquette in detail and gave fairly accurate descriptions of famous people: Kutuzov, Suvorov, Arakcheev... But he never mentioned the names of Emperors Alexander and Paul.

The Siberian elder received anyone who wanted to and was always ready to give advice and provide all possible assistance. Among the acquaintances there were also influential people, such as Macarius, Bishop of Tomsk and Barnaul, and Athanasius, Bishop of Irkutsk.

Many then considered him bishop- defrocked, until one day a retired soldier Olenyev, passing through the village of Krasnorechenskoye, recognized the late emperor in Fyodor Kuzmich. This gave food for rumors and gossip. The rumor about the Siberian elder spread throughout Russia.

Among Fyodor Kuzmich’s friends was a wealthy Tomsk merchant, whom the elder met in 1857. Later, the merchant invited him to move to Tomsk, where he built a cell especially for him.

Fyodor Kuzmich agreed to this generous offer and left Zertsaly.

Before the death of the elder, the excited merchant asked him:

“The rumor is that you, Fyodor Kuzmich, are none other than Emperor Alexander the Blessed. Is it so?"

The elder, still in his right mind, answered him:

“Wonderful are your works, O Lord; there is no mystery that will not be revealed. Even though you know who I am, don’t make me great, just bury me.”

According to the will left by the elder, two objects were delivered to St. Petersburg - a cross and an icon. It was these items from Alexander’s belongings that disappeared after his death.

In this chapter we examined the circumstances of the death of Alexander and the life of the mysterious elder Fyodor Kuzmich

Conclusion

Whether Emperor Alexander really died or all this was a carefully planned show, we will most likely never know. But nothing prevents us from speculating a little on this topic.

Consider the first hypothesis. Despite all the oddities and evidence in favor of the second version, Alexander’s death in Taganrog looks quite likely. Firstly: at the death of the sovereign, many courtiers were present. And what, they were all initiated into the emperor’s idea? Unlikely. In addition, a whole group of doctors took part in the events of that night, whom Alexander would not have been able to deceive with his feigned death.

Let's skip the circumstances of his death and move on to the wanderings of Fyodor Kuzmich. Let's say Alexander miraculously managed to fool all the witnesses to his death, or spend a lot of money bribing them. Let's hypothetically assume that the mysterious Siberian elder is the escaped emperor. Let me remind you that Alexander died in 1825, and the first mention of the elder dates back to the autumn of 1836. Where has Alexander been all these years? After all, what appears before the blacksmith is, albeit an elderly man, but a strong and broad-shouldered man, full of strength and health. But Alexander was by no means physically strong, was a poor rider and had poor health. But by the time he appeared in Krasnoufimsk he was almost 60 years old! And after this he lives for another 30 years! Incredible!

Let us remember the moment when the retired soldier Olenyev recognized Emperor Alexander in Fyodor Kuzmich. Where could Olenyev, a simple private, see the emperor? In war, in parades. But did he remember the features of the royal face so well that he could later see them in a simple tramp? Doubtful. In addition, Alexander has changed a lot since then: he has aged, grown a beard. It is unlikely that a soldier who saw the emperor only a couple of times remembered him enough to recognize him many years later, an aged, bearded, gray-haired old man living in remote Siberia.

Hypothesis two. What speaks in favor of an alternative version of events? Quite a lot. Strange events before and after the death of the emperor. The inexplicable actions of people close to Alexander, as if they knew something that others did not know. All this undoubtedly points to the second version of events. He managed to negotiate with those who were present at his apparent death to secretly get out of the city. Where did he disappear for ten years in a row? He lived on some forest farm, restoring his health. After 10 years, I finally decided to leave the forest and immediately felt in my own skin the “touching care” of our state for its citizens. After wandering around, he will settle in the village of Zertsaly, where he will begin educational activities. He amazed the dark peasants with his knowledge in the field of history, geography, and law. He was a religious and pious man. Another proof is deafness in one ear (Alexander lost his hearing in his youth during shooting in Gatchina). The elder also knew the intricacies of court etiquette. If this can be explained somehow (he was a servant of some nobles), then the exact characteristics that he gave to famous people cannot be explained.

Fyodor Kuzmich lived in a tiny hut-cell, was an ascetic and devoted a lot of time to God. All his life he had been atoning for some sin. If we adhere to the version that Alexander is the elder, then this sin may be parricide, which Alexander, while still an emperor, was extremely burdened by.

Another interesting point: when the soldier recognized Fyodor Kuzmich as the emperor, the fame of the mysterious old man spread throughout Russia. Did Alexander’s friends and relatives really know nothing about these rumors? And if they knew that, undoubtedly, why didn’t they order the execution of the daring impostor? Maybe because they knew that it was not an impostor at all? This is the most likely option.

And the last moment especially struck me. Although, perhaps all this is idle gossip of our inventive people. . According to its terms, a cross and an icon were delivered to St. Petersburg, things that belonged to Alexander and disappeared on the eve of his death. I will repeat and say that most likely this is fiction, but if suddenly it turns out to be true, then this case serves as irrefutable evidence of the second hypothesis.

Now the work has come to an end. I hope that the main goal of the work, covering the mysterious death of Emperor Alexander I, was successfully completed. In addition, Alexander was shown as a personality and historical character, not the worst, I must say. In fact, he lived two lives: the first, although not pure and noble in all places, but still worthy; and the second, bright and clean. Starting from scratch, Alexander definitely made the right decision. May you also be lucky when you start with a clean fox

List of used literature

Bulychev Kir (Igor Vsevolodovich Mozheiko), “Secrets of the Russian Empire”, Moscow, 2005

, “Royal Dynasties”, Moscow, 2001

“The Riddle of Alexander I”, http://zagadki. *****/Zagadki_istorii/Zagadka_Aleksandra. html

, “Rulers of Russia”, Rostov-on-Don, 2007

"Royal Dynasties", Moscow, 2002

"The Sphinx, unsolved to the grave"

http://www. *****/text/sfinks__ne_razgadannij_d. htm

Shikman A., “Who is who in Russian history”, Moscow, 2003.

Application

Alexander I Blessed

Application 2 .

Secret committee

The mysterious Siberian elder Fyodor Kuzmich

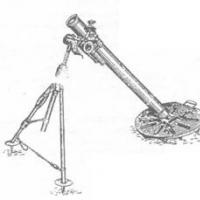

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force

US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force Differentiation of functions

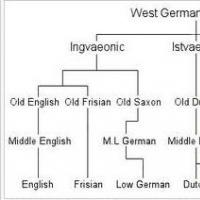

Differentiation of functions Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages

Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages Which scientist introduced the concept of valency?

Which scientist introduced the concept of valency? How does a comet grow a tail?

How does a comet grow a tail?