Nikolai Bunge. Nikolai Khristoforovich Bunge. Establishment of the Peasant Bank

Other countries

Economists by the grace of God. Nikolay Bunge

A major theorist, he showed himself to be an unsurpassed practitioner, created a stable financial system and became the first herald in official Russia of the need for social policy.

~~~~~~~~~~~

Nikolay Bunge

Today our country is faced with financial and economic problems similar to those faced in the second half of the century before last. That experience remains undeniably interesting.

Of particular value are the practical activities of the Ministry of Finance and the theoretical developments of the economist who headed it. Nikolai Khristianovich Bunge(1823-1895). He headed the department from 1882 to 1887.

Bunge's ancestors were of Swedish origin; diligence, love of knowledge, discipline, and abstinence in everyday life were cultivated in the family. After graduating from Kyiv University in 1845, St. Vladimir Nikolai Bunge was sent to the department of laws of government administration at the Nizhyn Lyceum of Prince Bezborodko (which had the status of a higher educational institution).

Just two years later, at the age of 24 (!), a recent graduate, having defended his dissertation “A Study of the Beginnings of the Trade Legislation of Peter the Great,” becomes a Master of Public Law. And in 1850, Bunge was awarded the degree of Doctor of Political Science for his dissertation “The Theory of Credit.” In development of these works, he prepared and published “A Course in Statistics” (1865) and “Foundations of Political Economy” (1870). Analyzing foreign practice in detail, Bunge persistently recommended limiting the circulation of banknotes in favor of metal and non-cash payments. He came to the conclusion that paper, “often multi-zero” money provokes inflation and thereby depreciates circulation. These issues are presented in detail in Bunge's books and articles. He also translates and supplements with his comments the works of foreign authors.

Blacksmith shop. End of the 19th century.

It is no coincidence that Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky noted that Bunge “was a very strong theorist and came to the post of minister as a conscientious scientist who, among other things, was well acquainted with the economic and financial policies of the West.” Bunge was elected rector of Kyiv University three times. The first time was in 1859 on the recommendation of the famous Pirogov, surgeon and hero of Sevastopol. The nomination of such a young professor as rector was unprecedented in the history of the university. But it was explained by the changes that took place in public life. Alexander II, the Liberator, became Emperor. And, as soon as he assumed the duties of rector, Bunge was summoned to St. Petersburg to participate in the work of the Editorial Commissions established to prepare a bill on the abolition of serfdom. He became a member of the Financial Commission, which was entrusted with creating a model of buyout operations.

Bunge worked in Kyiv for three decades. He taught numerous courses, and in his publications tried to reveal the best practices of those foreign countries that have overtaken Russia in socio-economic development. At the same time, he took an independent position in science. Based largely on the ideas of Adam Smith, Bunge at the same time believed that prices are determined by supply and demand. He believed that the driving force of social development was the desire of people to satisfy their needs through “useful activity,” which consists not only in the production of consumer goods, but also in scientific, cultural, and educational activities. “The economic structure of human societies... develops along with the successes of education, welfare and morality, along with the expansion of the range of activity of both public power and individual initiative. A well-ordered society is not an inevitable form of freely formed private relations, as Smith's followers thought, but is the result of the continuous combined action of government and people."

Under Bung, the Kiev school of economic thought emerged. Its representatives were united by the denial of the labor theory of value, rejection of the socialist doctrine, recognition of the need for social reforms, and primary attention to practical issues of economic policy. Bunge's influence on representatives of the school is vividly described by its prominent representative Dmitry Pikhno. “What attracted us, young students, to this cautious thinker, whose auditorium was full of listeners and almost every episode produced young economists who worked enthusiastically under his leadership? It was another, more intimate, spiritual connection invisible to the prying eye... This cold-looking sage was completely imbued with an unattainable moral idealism, behind his ironic smile, which so often confused and which we were so afraid of, the gentle, loving, sympathetic and an infinitely kind heart."

In one of his first (1883) detailed reports to Emperor Alexander III, Bunge noted: “A careful study of the weaknesses of our political system indicates the need to ensure the correct growth of industry with sufficient protection for it: to strengthen credit institutions on principles proven by experience, while also helping to reduce the cost loan; to strengthen the profitability of railway enterprises in the interests of the people and the state by establishing proper control over them; to strengthen credit money circulation through a set of gradually implemented measures aimed at achieving this goal. Next, introduce reforms in the tax system that are consistent with strict fairness and promise an increase in income without burdening tax payers; finally, to restore the excess of income over expenses (without which improvement of finances is unthinkable) by limiting excessive loans and maintaining reasonable frugality in all sectors of management.”

Peasant Bank. Kyiv.

Bunge's accession to the post of Deputy Minister of Finance in 1880 and soon, from January 1, 1882, Minister marked a new stage in Russian monetary policy. In the appointment of a scientist to a post in the government, many saw recognition of the high authority of science and the need for special knowledge. But the work had to begin in very difficult circumstances. The amount of public debt on January 1, 1881 exceeded six billion rubles. New loans were coming - internal and external. The main reasons were the financial consequences of the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878 and the colossal government expenditures on peasant and subsequent reforms. To prevent a systemic crisis, Bunge initiated the issuance of the 1883 gold six percent annuity on income. This improved the financial situation. Maneuvering and making compromises, Bunge was steadfast in protecting treasury revenues. The angel of meekness and kindness turned into Hercules of iron will and said “impossible” to a request for money not only to the chairman of the ministers, but to the sovereign himself.

The emperor approved this program of long-term financial policy of the state, and in subsequent years it was implemented almost completely (except for the clause on excess - due to the large costs of repaying government loans).

One of the first financial measures carried out by Bunge was the reduction of redemption payments for peasants. It was carried out in the amount of 1 ruble from each per capita plot within the Great Russian borders and 16 kopecks per ruble in other areas. The total amount of the reduction was 12 million rubles per year. The partial liberation of peasants (except for the sovereign) from the poll tax in 1886 is also the merit of Bunge. This decision contributed to increased agricultural productivity. Due to the stabilization of peasant incomes, the demand for equipment began to grow.

Bunge was a supporter of state protectionism and a strict tax system. During his leadership of the Russian Ministry of Finance, taxes on sugar, alcohol, and tobacco were increased. Stamp duty and duties were increased on approximately 35% of the range of Russian consumer imports. In addition, a ten percent surcharge on all import tariffs was established in 1881. This was followed by an increase in import duties on rolled iron, steel, technical machinery, and some types of sea and river vessels. At the same time, a tax was introduced on gold mining and processing of precious metals; additional and distribution fees from commercial and industrial enterprises (laws of July 5, 1884 and January 5, 1885). The rates of most other taxes increased. These measures made it possible to reduce the state budget deficit by almost 90% by the end of the 1880s.

However, Bunge argued that “ordinary customs duties constitute a tax and should be considered primarily as a tax. They should depend as little as possible on trade agreements (that is, not be a support for protectionism - A.Ch.), they should be correlated with the general system of taxes, with their influence on production, trade and consumption. Encouragement of industry can and should take place, but protective tariffs and benefits, common to all persons, give encouragement to everyone indiscriminately and are therefore not always desirable. Such benefits often indicate inefficiency in the state economy. A liberal customs tariff promotes increased consumption, but low customs duties with high taxes in the country are undesirable.” The mentioned problems, oddly enough, have not lost their relevance even after 130 years.

Banking services for the peasantry are also largely the merit of Bunge. He believed that the main problems of this social group were related to the insufficient size of land plots and the inability to obtain long-term credit to expand their land. To resolve these issues, the Peasant Bank was created. He issued loans for the purchase of privately owned, primarily noble, lands. In 1883-1915, over a million peasant households used the bank's services. They acquired more than 15.9 million acres of land (this is more than the territory of modern Austria, Switzerland and Slovenia combined). The total amount of loans issued exceeded 1.35 billion rubles.

In addition, Bunge initiated the active development of the all-Russian railway network and especially interregional highways, which, in his opinion, “given the spaces, national and economic characteristics inherent in the Russian state, are of the utmost importance.” In 1881-1889, about 133.6 million rubles were spent on the construction of communication routes. 3461 miles of railways were laid. Steel arteries connected the Volga region, the Middle Urals, the Black Earth Region, the North Caucasus, Bessarabia and some areas of Central Asia.

Baku oil fields. End of the 19th century

Among the reforms implemented by Bunge is the law of June 1, 1882, which for the first time in Russia regulates factory labor, including the length of the working day, the parameters of overtime payments, and social guarantees for workers and their families. In 1886, regulations for the hiring and supervision of enterprises were issued.

As the Russian statesman, scientist and entrepreneur Vladimir Kovalevsky recalled, “Bunge was the first finance minister who proceeded from the firm and clear consciousness that narrow “financialism” - exclusive concern for public finances in a narrow sense - should be replaced by “economism” - a broad economic policy aimed at developing the people’s labor and productive forces of the country, and that even a satisfactory state of the state cannot be achieved with poverty, lack of rights and darkness of the mass of the population.”

In life, Nikolai Khristianovich Bunge was, according to eyewitnesses, a very modest person. Going to Gatchina, he went to the station in a simple cab. Of his income (20 thousand rubles per year), he spent only a part, sending the remaining amounts to the cash desks of charitable institutions for the poor and students. Moreover, he did this anonymously; the fact was revealed only after his resignation.

By the way, the germs of the ideas of social policy are contained in the works of Bunge from the pre-ministerial, Kyiv period. Thus, in his work “Police Law,” the scientist especially emphasized the role of workers in the profits of joint-stock companies, which he called “partnerships of the new time.” He (the worker - A.Ch.) “is told: we give you, as a participant, as a shareholder, the rights of a capitalist and owner; you can have a voice in a common matter, and if you have knowledge and talent, then we give you the responsibilities of a head and a leader, even if you have no capital.” For modern Russia, these recommendations are extremely relevant.

Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Leonid Abalkin, who drew attention to the fundamental principles of Bunge’s economic views, was annoyed that a century later they were still underestimated. They also discussed the creation of loan banks, which Bunge considered a means of increasing the material well-being of workers. It could be raised both by “productive partnerships” and by societies created to educate workers, build apartments, issue pensions and benefits, credit and consumer cooperatives. In this regard, the task of the state “is to establish legal norms in order to ensure the emergence and activity of new economic unions with the rights of legal entities.”

At the end of his life, Bunge, who had previously lectured for the heirs to the throne, drew up a political will addressed to Nicholas II (“Notes after the Grave,” 1893-1894). In it, relying on his own research, international economic experience and the results of ongoing reforms, the scientist advocated moderate - gradual, systemic, based on Russian specifics - reformism. He also proposed a greater level of social independence and advocated the comprehensive development of national borderlands while preserving their identity. Bunge actually proposed a “drift” of the Russian Empire towards an “enlightened constitutional monarchy,” as Dmitry Merezhkovsky outlined the goal.

In a word, the activities of Nikolai Khristianovich Bunge are a set of interrelated measures to strengthen the state financial and economic system, as well as Russia’s foreign trade positions, and carry out the overdue reforms that strengthen the power.

Brief biographical information about N.Kh. Bunge. Nikolai Christianovich Bunge (1823-1895) was one of the outstanding Russian reformers in the field of economics, finance and social policy. He graduated from the Faculty of Law of Kyiv University and taught at the Nizhyn Lyceum. After defending his master's thesis in 1847 on the topic “A Study of the Beginnings of the Trade Legislation of Peter the Great,” in 1850 he went to work at Kiev University, where in 1852 he defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic “The Theory of Credit.” The range of his scientific interests was very diverse: he gave courses of lectures on political economy, statistics, police law and other sciences. From 1859 to 1880 he was the rector of Kyiv University. During these years, he was involved in the preparation of the peasant reform of 1861 and the development of a new university charter. As one of the prominent economists, he was invited to teach political economy to the heir to the throne, Tsarevich Nicholas.

Bunge gained considerable experience in practical work while working since 1865 as the manager of the Kyiv branch of the State Bank. In 1880, he was invited to work in St. Petersburg as a fellow minister of finance, and from 1881 to 1886 he served as minister. After his resignation, from January 1887 until his death in 1895, N.Kh. Bunge was Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers. Traits of Bunge the Reformer:

- He was characterized not by “narrow financialism”, but by a broad, comprehensive approach to economic and financial problems, which he closely linked with the social policy of the state.

- He considered the goal of financial and economic policy not so much to fill the state budget as to increase the well-being of the lower classes, since the prosperity of the state depended to a decisive extent on this. To this end, he implemented a number of drastic measures to ease the tax burden of the peasantry.

- He always balanced his reform plans with the real situation, public opinion, and knew how to wait, retreat, and compromise. He prepared the planned reforms carefully, without haste.

Economic and Financial Policy Program. His transformative activities N.Kh. Bunge started out in unfavorable conditions. First of all, the severe financial consequences of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878 affected. - huge budget deficit, depreciation of the ruble. The national debt as of January 1, 1881 amounted to 6 billion rubles. - the amount was astronomical for that time. From 1881 to 1883, Russia experienced an economic crisis, and from 1883 to 1887, a depression. 1880s were also characterized by local crop failures; The situation in the countryside was aggravated by a reduction in land plots due to the rapid growth of the rural population, an increase in the number of landless households, and a heavy tax burden.

On behalf of Alexander II, who treated Bunge with great respect, the latter in 1880, being a comrade of the Minister of Finance, prepared policy note on the tasks of economic and financial policy for the coming years. It included the following main provisions:

- 1. Reducing government spending.

- 2. Cessation of the issuance of paper money, a gradual reduction in their quantity to the pre-war level.

- 3. Organized resettlement of land-poor and landless peasants to undeveloped government lands.

- 4. Streamlining taxes: abolition of the poll tax, salt tax and passport fee; reduction in redemption payments. To compensate for losses, it was envisaged to increase the state land tax levied on non-taxable estates, increase the tax on city real estate, and establish taxes on individuals in the liberal professions (lawyers, doctors, architects, artists, etc.), on commercial and industrial enterprises and monetary capital. Bunge considered these changes as measures preparing the introduction income tax.

- 5. Making laws to promote industry and trade.

- 6. Streamlining the financial side of things in railway construction in order to stop the waste of public funds.

This program was accepted. And when in 1881 the Minister of Finance A.A. Abaza, along with other liberal ministers, resigned, and was replaced with the approval of Alexander 111 N.H. was appointed. Bunge.

Tax reforms. Bunge gave priority attention to taxation policy. The Minister of Finance was most concerned about redemption payments. Their exorbitant burden for the peasants became apparent immediately after the start of the reform. Already in the first five years - 1862-1866. - arrears amounted to 7.9 million rubles. 1 The then Minister of Finance M.Kh. Reitern organized an investigation into the causes of arrears, and it turned out that redemption payments significantly exceeded the profitability of peasant farms. In 1880, arrears amounted to 20.5 million rubles, in 1881 - 23.4 million.

In April 1881, the State Council decided to transfer all former landowner peasants to “compulsory redemption” and to add up arrears on redemption payments of 14 million rubles. and a reduction in redemption payments by 9 million rubles. per year (later the amount of the annual reduction amounted to 12 million rubles). In connection with the coronation of Alexander 111 in 1883, another 13.8 million rubles were written off. arrears on these payments, in 1884 - 2.3 million rubles.

Another “headache” for the Minister of Finance was capitation tax. In March 1882, Bunge submitted a note to the State Council “On replacing the poll tax with other taxes,” in which he substantiated the impossibility of further delaying the abolition of the tax. Arrears on the poll tax constantly accumulated, which were written off from time to time. So, in 1880, 7 million rubles were written off; in 1881, arrears amounted to 10.7 million rubles. The State Council approved the phased abolition of the poll tax proposed by Bunge. Since 1883, the collection of taxes from the categories of the population most burdened with taxes ceased. On January 1, 1887, the collection of the poll tax was stopped from all other payers.

For 1882-1887 per capita tax receipts decreased from 54.8 million rubles. up to 1.3 million 1.

To compensate for the losses, Bunge introduced a number of new taxes and increased the previous ones. In particular, the land tax introduced in 1875 was increased by 52.5%; the tax on real estate in cities was increased by 46%; the fishing tax system was transformed, some benefits were given to small traders and artisans; in 1885, a 3% tax was introduced on the net profit of joint-stock companies; in the same year, a 5% tax on income from monetary capital was established; in 1887, a 5% tax was introduced on government-guaranteed income from shares of private railways; a duty was introduced on property passed on by inheritance, which caused acute discontent among the nobility.

In 1885, in connection with changes in the tax system and its complication, Bunge established a special institute of tax inspectors at the provincial treasury chambers. They were designed to identify taxable income from real estate and other objects.

Bunge's tax reforms were highly praised by the liberal public. For example, the famous liberal publicist S.N. Yuzhakov believed that Bunge’s actions eased the situation of the people and saved them from final ruin. Modern historian V.L. Stepanov points out that Bunge’s tax reforms “laid the beginning of the modernization of the Russian tax system and thereby contributed to the process of industrialization of the country.”

Transformations in banking. Bunge continued to develop the system of state lending to the national economy, since government loans have long enjoyed greater confidence in Russia than private ones. Lending expanded through National Bank, which stably kept the discount rate at 6% and only in 1886 reduced it to 5%. In 1881 - 1884, despite the industrial crisis, the issuance of loans increased from 180 million rubles. up to 204 million

Under the leadership of Bunge in the first half of the 1880s. in Russia a system has developed state mortgage loan. During these years, landowners continued to mortgage low-income estates in joint-stock land banks, but did not redeem them in a timely manner, which led to the sale of the mortgaged lands. For example, from 1873 to

In 1882, 23.4 million dessiatines were sold. Bunge had the idea to organize cheap credit for peasants so that they would become the main buyers of the landowners' land. The Ministry of Finance has prepared an education project Peasant Bank, which was approved by the emperor on May 18, 1882. The main provisions of the law on the Peasant Bank were the following: 1) loans are allocated to all willing peasants, regardless of their property status, at 6% per annum; 2) the loan amount is 75% of the cost of the acquired land; 3) loan repayment terms are set from 24 to 34 years; 4) the bank is an independent credit institution and is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance.

During 1883-1885. 25 branches of the Peasant Bank were opened in Russia; the amount of loans during this time increased from 864 thousand to 14 million rubles, the amount of purchased land - from 18.2 thousand to 318 thousand dessiatinas 1. Since 1886, land sales have been declining due to the creation of the Noble Bank. In just the first 13 years of the Peasant Bank's existence, peasants bought, with its assistance,

- 2411.7 thousand acres of land.

- June 3, 1885 Alexander 111 signed a decree on consciousness of the Noble Land Bank; Thus, the formation of the mortgage loan system was completed. This bank also operated under the auspices of the Ministry of Finance and issued loans secured by land property in the amount of 60% of the value of estates for a period of 36 to 48 years with an annual payment of 5%. Thus, the conditions of the Noble Bank were extremely favorable. However, as subsequent practice showed, they were unable to stop the process of reducing landownership.

Immediately there was a great demand for loans. In 1886, in 25 branches of the Noble Bank, landowners received 68.8 million rubles, in 1887 - 71.1 million rubles. However, borrowers did not always use the loans for their intended purpose; they were often consumed or turned into stock market speculation, and interest arrears began to grow. However, in 1889 the loan interest rate was lowered to 4.5. Landowners who could not or did not want to organize a profitable farm sold their lands through the Noble Bank. The buyers were nobles (up to 50%), peasants (up to 20%), merchants and townspeople (up to 10%), and representatives of other classes.

Along with the development of public credit, Bunge also paid attention to private credit. He believed that the accumulation of financial resources in banks and savings banks would reduce the country's dependence on foreign capital. In 1883, the bans on the establishment were lifted commercial banks. Although this did not lead to an increase in the number of banks, deposits in them increased significantly. For example, by the end of 1892, only 6 new banks had emerged, but deposits during this time increased from 214 to 301 million rubles. 1 The State Bank constantly supported commercial banks with its financial resources.

Bunge actively contributed to the development of the network in Russia savings banks. In May 1881, the interest rate on deposits was increased from 3 to 4, which contributed to the influx of new deposits into the cash desks. In 1884, the Ministry of Finance granted the right to create savings banks at provincial and district treasuries, and their branches in all cities and large towns. If in 1880 there were only 76 savings banks in the country, then in 1886 there were 554 cash banks, 306 thousand depositors and 44 million rubles. deposits

Thus, the Russian credit system, which was under state control and strictly regulated by relevant legislation, was raised to a new level. This created certain guarantees for commercial banks, including citizens’ deposits.

Other transformations of Bunge in the financial sector. Continuing the course of M.Kh. Reiterna, Bunge consistently pursued the policy protective tariffs. In 1882, import customs duties were increased on raw materials and manufactured goods and, to a small extent, on finished products. In 1884, duties on cast iron, coal, and peat were increased; in 1885 - for fish, wine, tea, vegetable oil, silk, agricultural machinery, iron and steel; a general increase in tariffs was carried out from 10 to 15%. If in 1881 the duty along all Russian borders was 16.5% of the value of imported goods, then in 1886 it was 27.8%.

Under Bunga it began to force itself export of bread, which was sold to Germany, England, Holland, France, Italy, Belgium. In 1881-1885 bread exports increased from 208 million to 344 million poods.

For strengthening of the ruble exchange rate Since 1881, Bunge stopped issuing money and began to withdraw unsecured money from circulation. The minting of silver coins was again allowed, although Bunge understood that Russia needed to switch to golden monometallism; however, this required a lot of preparatory work and an increase in gold reserves.

Labor legislation. N.H. Bunge was one of the few Russian statesmen who understood the need to develop laws on work issue. He believed that the legal regulation of relationships between entrepreneurs and workers should contribute to: 1) eliminating the causes of conflicts in enterprises and the decline of the strike movement; 2) reducing the prerequisites for socialist propaganda among workers; 3) improving working conditions at industrial enterprises and increasing worker productivity. The development of appropriate legislation was also encouraged by the growth of the labor movement in the 1870s and early 1880s.

The first to be developed was a law limiting the working day for children and adolescents and creating a factory inspectorate to monitor the implementation of the law. It provided for the prohibition of labor for children under 12 years of age, night work for children 12-14 years old, limiting the working day of adolescents to 10 hours, and compulsory attendance of children at school. Under pressure from entrepreneurs, the implementation of the law was delayed for a year (until May 1, 1884). In 1885, a law was passed prohibiting night work for women and adolescents under 17 years of age in the textile industry.

Bunge, Nikolai Khristianovich - financier, economist and statesman (1823 - 95), comes from nobles of the evangelical confession, was born in Kyiv, where his father was considered an experienced physician in childhood diseases; He received his education at the 1st Kiev gymnasium and at the University of St. Vladimir, where he graduated from the course in 1845. At the same time, Bunge was appointed as a teacher at the Lyceum of Prince Bezborodko, and after defending his master’s thesis in 1847, “A Study of the Beginnings of the Trade Legislation of Peter the Great” (“ Domestic Notes", 1850) was approved by the Lyceum professor. In the dark outback of Nizhyn he appeared as an ardent missionary of European science and citizenship; as a professor, he was actively concerned about raising the level of development of his listeners: in order to make the treasures of European science accessible to his chosen students, Bunge gave lessons in foreign languages in his apartment. Bunge retained this rare and attractive trait - to love everything young and sense everything gifted in the young - when (in 1850) he became a professor at the University of St. Vladimir, and this is the key to the extraordinary success of his university lectures. In 1852, Bunge was awarded the degree of Doctor of Political Sciences by the University of Kyiv for his dissertation “The Theory of Credit” (Kyiv, 1852). In 1869 he changed the department of political economy and statistics to the department of police law. Police law does not seem to Bunge to be a complete science; in the doctrine of security (laws of deanery) he sees a part of state law, and in the doctrine of welfare (laws of improvement) - an applied part of political economy. In accordance with this, in his course “Police Law” (Kyiv, 1873 - 77), which remained unfinished, and in which he managed to outline some departments of improvement, the economic point of view prevails. Bunge's police law corresponds to what is now known as economic policy. When presenting the theory of economic policy, the author does not limit himself to general principles alone, since, in his opinion, the study of general laws alone without connection with the facts in which these laws are found easily degenerates into dry and abstract scholasticism, which may be of interest to specialists, but is powerless resolve life issues. Bunge also published for his students “A Course in Statistics” (Kyiv, 1865; 2nd ed., 1876) and “Foundations of Political Economy” (ib., 1870). During the difficult days of university life, when universities were deprived of self-government, Bunge served as rector by appointment (from 1859 to 1862). ) stood with dignity at the head of Kyiv University. But even after the return of voting rights to universities, Bunke was twice elected rector of the same Kyiv University and held this position from 1871 to 1875 and from 1878 to 1880. In 1880, he left the university. Bunge was one of those professors who do not confine themselves to the blank walls of their office. Possessing a bright and broad mind, he could not help but respond to the social issues that life brought to the fore. The result was a whole series of articles that he published in various periodicals, starting in 1852. These were articles related to the then expected peasant reform (in "Domestic Notes", 1858, and in "Russian Bulletin" 1859, No. 2 and 8 ), to the spreading new type of industrial enterprises in the form of joint-stock companies (in the "Magazine for Shareholders", 1855 and 1858) and many others, among which one cannot fail to note his comments on the structure of the educational department at universities (in the "Russian Bulletin" 1858. , vol. XVII) and banking policy (in the "Collection of State Knowledge", vol. I, 1874). His study “Commodity Warehouses and Warrants” (Kyiv, 1871) was also of great practical importance; But Bunge’s research on ways to restore correct monetary circulation in our country, shocked by the excessive issue of paper money, attracted special attention. These include the works: “On the restoration of metal circulation in Russia” (Kyiv, 1877); “On the restoration of a constant monetary unit in Russia” (Kyiv, 1878) and articles in the “Collection of State Knowledge”, vol.

VI, 1878, and volume XIII, 1880. Bunge also translated and expanded A. Wagner’s work “Russian Paper Money” (Kyiv, 1871). In 1859, when the peasant reform was maturing, Bunge was invited to participate in the financial commission, whose purpose was to find the grounds and methods for the final resolution of the peasant issue through the redemption of plots with the assistance of the government. Called again to St. Petersburg to participate in the discussion of the new university charter (1863), Bunge received an assignment to teach the science of finance and political economy to the heir, Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich. Bunge based these lectures on Carl von Gock’s book “Taxes and State Debts” (Kyiv, 1865), which he translated into Russian. Upon returning to Kyiv, Bunge, without leaving university studies, accepted the position of manager of the Kiev office of the state bank. Thus, standing at the very source of credit operations, Bunge had the opportunity to test in practice the instructions of the theory of finance. From that time on, his voice acquired decisive importance in financial matters. Bunge's accession to the post of Comrade Minister of Finance in 1880 and soon afterwards in 1881 as Minister of Finance was met with sympathy and great hopes. - Bunge is the Minister of Finance. Bunge had to take over the management of the ministry under very difficult circumstances. The reaction that occurred after March 1, 1881 was also reflected in the financial condition of the country. In addition, two years in a row - 1884 and especially 1885 - were marked by almost universal crop failure, and this caused adverse consequences for industry and trade. Bunge's first budget of 1881 had to be reduced to a deficit of over 50 million rubles. The amount of the national debt on January 1, 1881 reached over 6 billion, and it was inevitable that a number of new loans would be concluded. One of Bunge's first actions was the issue of a 6% gold annuity in 1883, which, due to the extremely high interest rate, met with an unfriendly attitude in society. The state of the credit ruble exchange rate was very unsatisfactory. In 1881, the average price of the ruble was 65.8 kopecks in gold, in 1886 - 58.9; the balance of payments was extremely unfavorable, and on foreign exchanges, especially in Berlin, speculation was carried out with Russian funds and credit rubles, against which Bunge, guided by a system of non-interference in exchange relations, did not take appropriate measures. In one of his first all-subject reports (1883), Bunge defined his financial program as follows: “A careful study of the weaknesses of our political system indicates the need to ensure the correct growth of industry with sufficient protection for it: to strengthen credit institutions on principles proven by experience, while helping to reduce the cost credit; strengthen, in the interests of the people and the state, the profitability of railway enterprises by establishing proper control over them; strengthen credit money circulation through a set of gradually implemented measures aimed at achieving this goal; introduce changes in the tax system, consistent with strict fairness and promising an increase in income without burdening tax payers ; finally, to restore the excess of income over expenses (without which improvement of finances is unthinkable) by limiting excessive loans and maintaining reasonable frugality in all sectors of management." Of this program, Bunge certainly failed to meet the excess of revenues over expenses, due to the significant costs of urgent repayment of government loans. In all other respects, the time of Bunge's management was truly an outstanding era in the history of Russian finance. One of the first financial measures was the reduction of redemption payments, which Bunge considered necessary to improve the well-being of the rural population, and which was urgently caused by the fact that, in general, more was collected from the peasants than was paid under the obligations of the redemption operation. The reduction was made in the amount of 1 ruble from each per capita allotment subject to redemption payments in

Great Russian localities and 16 kopecks per ruble in Little Russian localities. The total amount of the reduction was up to 12 million rubles per year. In 1885, Bunge entered the State Council with the idea of a universal (except for Siberia) abolition from January 1, 1886 of the poll tax, which had been the cornerstone of our financial system since the time of Peter the Great. This measure was supposed to reduce the resources of the state treasury by 57 million rubles, part of which was supposed to be compensated by increasing the tax on alcohol (up to 9 kopecks per degree), and part by increasing the quitrent tax from state peasants (which the government refused to increase by 20 in 1886). years). The State Council, however, decided to transfer the state peasants to redemption, which in reality was nothing more than a disguised increase in the quitrent tax. The law of June 12, 1886 established compulsory redemption for state peasants. The abolition of the poll tax should have entailed the abolition of mutual responsibility. And in 1885, Bunge, in his presentation to the State Council, pointing out the ruinous consequences of this method of collecting taxes, which causes, on the one hand, “attachment of peasants to the land by the passport system”, on the other, “the desire for unauthorized absence to seek better earnings,” spoke out in favor of abolishing mutual responsibility. The State Council did not agree with Bunge's arguments, and mutual responsibility was left for taxes that replaced the poll tax. In any case, we owe the abolition of the poll tax and the reduction in redemption payments of the landowners exclusively to Bunga, who took an extremely bold step by refusing income of up to 70 million rubles at a time when the budget was running a deficit. This significant decrease in income forced Bunge to turn to other sources and - above all - to increasing taxes. Thus, under Bung, taxes were increased, except for the tax on alcohol (first to 8 kopecks according to the law of May 19, 1881, then to 9 kopecks per degree, according to the law of May 18, 1885), on sugar (May 12, 1881) , on tobacco (May 18, 1882); Stamp duty was increased (January 19, 1882), customs rates were increased on many imported items, and transit through Transcaucasia was closed; a tax on gold mining was introduced, additional and variable fees were established on commercial and industrial enterprises (laws of July 5, 1884 and January 5, 1885), the tax on real estate in cities was increased (May 13, 1883), and the land tax was increased, a tax on income from monetary capital and a tax on the transfer of property without compensation (donation and inheritance tax) were introduced, taxes on foreign passports were increased, and the sale of drinks was regulated. Along with these tax reforms, Bunge took care of the introduction of the institution of tax inspectors, which was supposed to ensure a more correct receipt of taxes. The new state credit institutions established under Bung were of great importance for the further economic development of Russia. Based on the point of view that the economic disorder of the peasants occurs mainly as a result of the insufficiency and low productivity of their land plots, and the acquisition of other lands into ownership seems extremely difficult for the peasants due to the inability to use long-term credit, Bunge developed a project for a state mortgage bank to assist peasants in their acquisition of land. The bank's charter was approved by the Highest on May 18, 1882. Loans were to be issued in 51/2% mortgage sheets, called 51/2% state certificates of the peasant land bank. By its very charter, the bank was supposed to be only an intermediary between peasants and landowners who were already making a deal on their own initiative. And from the very beginning, the purpose of the bank, as stated by the motives of the state council, should have been to assist wealthy peasants who had some income, but not those with little land. The bank began operations on April 10, 1883, and by the end of Bunge's ministry, by 1886, had at its disposal a reserve capital

l at 467.7 thousand rubles. Along with this bank, a noble bank was also opened, which was established specifically “to help the nobility.” According to Bunge's idea, the bank was supposed to issue loans only to those noble landowners who themselves managed their land. But the State Council accepted Bunge's project, eliminating any restriction. Under Bung, the construction of state-owned railways was greatly expanded. For this purpose, under Bunga, up to 133.6 million rubles were spent; The treasury built railways with a total length of 3461 miles. In addition, several lines of private companies were purchased for the treasury. Bunge himself doubted that “the conversion of railways into state property would immediately enrich the treasury,” but he saw that “over time, railways could become the same branch of the state economy as mail and telegraphs.” Despite the lack of a plan for the purchase of private roads and state railway construction and the huge deficits from the operation of railways, it was Bunge who contributed greatly to the streamlining of our railway policy, and with it Russian finances in general. Bunge's management of the Ministry of Finance was marked by the triumph of protectionism. Bunge's activities coincided with the nationalist course of domestic policy. The ideal of independence of the national economy, its liberation from foreign domination, preached with particular energy by the Moskovsky Vedomosti and then by Mendeleev, led to demands for increased duties. A certain influence on the protectionist direction of foreign trade policy under Bunge was exerted by the general rise of the customs-protective wave that swept across Europe and in particular in Germany, causing significant changes in the tariff system in 1879. In 1881, a 10% increase was made on the entire tariff. On June 16, 1884, there was an increase in the duty on cast iron, which was then joined by corresponding increases on rolled iron, steel, machinery, etc. In 1884, a general duty on coal was also established with differential taxation of coal imported through the Black Sea ports and western land border. One of Bunge's great merits as Minister of Finance is his desire to introduce an income tax in our country. Acute financial need in the late 70s and early 80s, caused partly by the Turkish war, partly by the reduction of a number of state resources due to tax reforms, and partly by general poor financial management, put a fundamental tax reform on the agenda. In his most comprehensive report for 1884, Bunge categorically and definitely recognized income tax as the most expedient and fair method of taxation. But, fearing a strong breakdown in economic relations, he did not dare to immediately begin introducing an income tax and for the first time established a number of private taxes, which had the meaning of measures preparing the introduction of one income tax. Among Bunge's reforms, it is necessary to indicate the first step towards the regulation of factory labor, expressed in the law of June 1, 1882, the beginning of a more correct organization of city and private banks, laid down by the rules of April 26, 1883, and the drinking reform of 1885. Few ministers had to endure so many attacks from the press, especially the Moskovskiye Vedomosti, and few treated them so calmly, without resorting to the defense of the punitive administration and limiting themselves to official denials of a strictly factual nature. In January 1887, Bunge resigned as Minister of Finance and was appointed chairman of the Committee of Ministers. Bunge was elected as an honorary member of various societies and universities: St. Petersburg, Novorossiysk, St. Vladimir and the Academy of Sciences; in 1890 he was elected an ordinary academician in political economy and published the book “Public Accounting and Financial Reporting in England” (St. Petersburg, 1890), which is interesting material for the study of budget law. In compiling this book, the author has benefited from a whole range of practical information supplied to him by our financial agents in Paris and London.

e. - Bunge - economist. Bunge considered competition to be the main factor in economic life. Not completely agreeing with any of the classics and finding significant irregularities in views like Hell. Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, Mill, as well as Carey and Bastiat, he adhered to an eclectic point of view, mainly adhering to the theories of Malthus and Mill. He considered supply and demand to be the main regulator of economic phenomena and explained almost all economic phenomena with them. Bunge's socio-political views were fully consistent with this view. Bunge recognized the enormous beneficial influence behind rivalry. Without competition there would be a huge decline in strength. Rivalry turns out to be disastrous when unequal forces enter into the struggle, on the one hand, united, supported by monopolies, privileges, and enormous capital, and on the other hand, fragmented, deprived of any support and unsecured in their activities. Evil, according to Bunge, lies not in competition, but in its insufficient balance. Nevertheless, Bunge did not see anything enslaving or humiliating in the purchase of living labor, i.e., in hiring labor, since this purchase is associated with mutual benefit. Bunge allowed state intervention in economic life only on a small scale and in extreme cases. This point of view did not, however, prevent Bunge from recognizing the advisability of government intervention in the field of trade policy and in the field of “measures related to strengthening the welfare of factory workers.” Bunge's practical measures while he was Minister of Finance established his reputation as a strict protectionist. In his theoretical views, which he outlined in the course “Police Law,” Bunge is not, however, an unconditional protectionist. According to Bunge, customs duties constitute a tax and should be considered mainly as to how to file. They should depend as little as possible on trade agreements and should be taken into account with the general system of taxes, with their influence on production, trade and consumption. Encouraging industry can and should take place. But a protective tariff and benefits, common to all persons, give incentives indiscriminately and are therefore not always desirable. Benefits often indicate inefficiency in the state economy. A liberal customs tariff promotes increased consumption, but low customs duties with high taxes are undesirable. As for laws regarding workers, it was precisely from the recognition of the beneficial effects of competition that Bunge believed that freedom of transaction would be violated if workers did not have the right to enter into agreements among themselves regarding the setting of wages. Disagreeing with representatives of the liberal school who objected to the benefits of strikes, Bunge, however, did not see in workers’ unions the makings for the proper development of social life and considered trade unions a step backward compared to medieval guilds. Considering the task of legislation in the field of economic life to be the protection of freedom of transactions, Bunge did not allow any restriction of private property rights. In his opinion, the injustice of the initial acquisition has been smoothed out over time, because the owner invests his labor, his capital in the land and pays taxes from the land. Economic freedom not only contributed to raising humanity to the highest level of well-being, but in the future it should also serve as an indispensable factor of development. Capitalist production and the dominance of competition give man hope for a better future and make him free. In his methodological views, Bunge aligned himself with the historical-statistical direction in political economy, but introduced a number of restrictions into it. Disagreeing with Roscher, Bunge believed that the historical direction could introduce unprincipled “opportunism” into science and practical life; he found dangerous the absence of any principles, foundations, rules and the adoption of historical examples for guidance, with an attempt to follow them in cases mistakenly recognized as similar to those already lived by humanity. Requiring great caution in

Using the deductive method, Bunge insisted that political economy adopt the method of positive knowledge, observation and experience. In addition to the “Historical Outline of Economic Doctrines,” first published in 1868 and giving a brief summary of the teachings of the most prominent economic thinkers, ranging from the mercantilists to the historical school, Bunge gave a detailed exposition in extensive articles specifically of Carey’s teachings (“The Theory of the Consent of Private Interests - the first political-economic doctrine of Carey", 1858) and J.-St. Mill ("J. St. Mill as an Economist", 1868). These articles, together with a small extract from Schmoller's articles on Menger, were attached to the "Historical Outline of Economic Doctrines" and, with significant critical additions, changes and amendments, were published in 1895 under the general title "Essays on Political-Economic Literature." This was Bunge's last work. - Wed: P. Migulin, “Russian State Credit” (I volume, Kharkov, 1899); Kovalko, “The most important reforms carried out by N.H. Bunge in the financial system of Russia” (Kyiv, 1901); I. Taburno, “Sketch overview of the financial and economic state of Russia over the past 20 years (1882 - 1901)” (St. Petersburg, 1904); M. Sobolev, “History of customs policy in Russia” (St. Petersburg, 1911); "Historical background on the introduction of income tax" (official publication); Schulze-Gevernitz, "Essays on the public economy and economic policy of Russia" (1901). S. Zagorsky.

The most prominent reformer of Russia at the end of the 19th century. There was also Nikolai Khristianovich Bunge (1823-1895) - Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire from 1881 to 1886, Chairman of the Committee of Ministers in 1887-1895.

In 1850 He defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic “The Theory of Credit.” Thus, the future Minister of Finance was one of the country's leading experts in the field of jurisprudence and credit theory. Reforms and reformers. Merezhkovsky D.S. - Bustard, 2007 pp. 55-58

The treasury of world economic thought includes the theoretical postulates of N. X. Bunge on the mechanisms of regulation of a market economy: “demand” and “supply”; "economic freedom of competition." Becoming in 1880 comrade (deputy) minister of finance, he was already in 1881. headed the Ministry of Finance. In this responsible position, N. X. Bunge was able to implement the theoretical ideas set out in courses on statistics, the fundamentals of political economy, and the development of ideas for economic policy. He specifically examined the question of the possibility of correct monetary circulation in the country, undermined by the excessive issue of paper money. Having studied the works of the representative of the German school A. Wagner, N. H. Bunge developed his ideas in relation to Russia.

He had to begin his activities as Minister of Finance in the difficult financial situation of the country. Budget 1881 was reduced to a deficit of 50 million rubles. The amount of public debt amounted to 6 billion rubles. The average price of the ruble reached 65.8 kopecks. gold, there was an unfavorable balance of payments. The situation was aggravated by crop failures in 1884 and 1885. On foreign exchanges, especially in Berlin, speculation with Russian securities and credit rubles was noticed.

Since 1881 N.X. Bunge is taking measures at the state level to prepare large-scale monetary reform. He justified the need to implement a number of measures in order to improve the financial situation of the country (1883) in reports and notes to Alexander III:

a) ensure proper growth of industry in conditions of patronage (protectionism) from the state;

b) strengthen government-led lending relationships by making credit cheaper;

c) direct credit to areas of production that have not become particularly attractive to private enterprise;

d) transform the tax system;

e) to achieve an excess of revenues over expenses in the state, “observing reasonable frugality in all branches of management.” History of Russia from the beginning of the 18th to the end of the 19th century. Ed. A.N. Sakharova, Moscow, AST, 2001 pp. 197-199

Achieving a deficit-free budget was hampered by significant expenses for urgent repayments of government loans.

N.X. Bunge understood that to carry out monetary reform it was necessary to increase cash receipts to the treasury, including through an increase in direct and indirect taxes. May 12, 1881 taxes on sugar and alcohol were increased; January 19, 1882 increased stamp duty; Customs duties on many imported goods have increased; introduced a tax on gold mining; May 18, 1885 tobacco tax increased.

The result was an increase in the country's gold reserves.

Treasury revenues increased due to new issues of government loans. The State Bank supervised these operations.

In the 1880s. N.X. Bunge organized the purchase of private railways by the treasury, while revenues from state roads were sent to the treasury. The role of the Minister of Finance in the creation in 1883-1885 was important. Peasant and Noble land banks. Being state-owned banks, they contributed to the formation of the land market in Russia.

20 years after 1861 a crisis was brewing in agriculture due to the incompleteness of redemption transactions for 15% of peasant families; insufficient sizes of allotment plots for effective management; striped; a number of lean years, etc.

The Ministry of Finance, trying to improve the situation, proposed reducing redemption payments from peasants; ceased in 1883 the state of being “temporarily obliged” for a certain number of former landowner peasants. The Peasant Land Bank was supposed to resolve the issue of loans for peasants. Article 1 "Regulations on the Peasant Land Bank" dated May 18, 1882. stated that the bank “is established to facilitate peasants’ means of purchasing land in cases where the owners of the land wish to sell and the peasants to purchase it.”

At the same time, the State Council explained to the rural population that there would be no “free assistance in land relations.” The state equally protected the interests of both landowners and peasants, but rural people could “to increase their allotment, buy this or that plot with the favorable assistance of the bank.”

However, the loans issued to peasants were not equivalent to the size of the land plots being purchased, so the peasants made additional payments for the land from their own funds.

The maximum loan sizes were set: 125 rubles. per male capita in villages with communal land use; 500 rub. for each individual householder in a household. Loans were issued with the permission of the Bank Council in cash. The bank received this money when issuing government interest certificates; their annual volume was about 5 million rubles.

At the same time, 10 out of 11 private land banks created in 1860-1870 successfully worked in parallel with the Peasant Land Bank and issued the bulk of cash loans to peasants until the beginning of the 1890s.

The activities of the Peasant Bank also revealed another feature: by 1895, instead of loans to rural societies, which had farms of varying economic power, loans began to be issued to partnerships consisting of wealthy peasants who were able to buy part of the land from the nobles. Thus, the Peasant Land Bank did not so much help peasants buy land as help nobles sell it as profitably as possible. Such characteristics confirm the contradictory nature of socio-economic processes in post-reform Russia until the early 1890s.

But objectively, the activities of the Ministry of Finance in those years and personally N.X. Bunge contributed to the development of the land market and capital market.

The demand for products and goods also increased from the urban population and its working part.

On the initiative of N.X. Bunge adopted the first acts of factory legislation. This took place in the context of the outbreak of workers' strikes. Shortening the working day and increasing wages led to an increase in the standard of living of workers. The growth of their purchasing power activated the domestic market.

The Noble Land Bank's main goal in its activities was to support the farms of landowners. According to the Regulations approved on June 3, 1885, loans were issued for 36 and 48 years only to hereditary nobles secured by their land property, i.e. The bank was a typical mortgage bank. Loans here were cheaper than at the Peasant Bank, by 1.75-2.25%.

A significant part of the loans went directly to cover the debt that was on the estates under collateral in joint-stock land banks, where higher interest rates were charged on loans. In addition, many nobles never learned how to manage things; they were ruined by brokers and intermediaries.

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm

Experience in the combat use of mortars Flight range of mines from a mortar 80 mm Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force

US Eighth Air Force Museum 8th Air Force Differentiation of functions

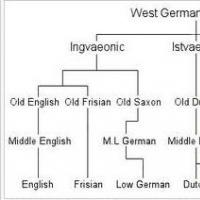

Differentiation of functions Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages

Classification of modern Germanic languages Main features of the Germanic group of languages Which scientist introduced the concept of valency?

Which scientist introduced the concept of valency? How does a comet grow a tail?

How does a comet grow a tail?