They served in the tsarist army for 25 years. How many years have you served in the Russian army before? Benefits based on professional affiliation

On February 23, Russia celebrates Defender of the Fatherland Day. During Soviet times, it was established as a holiday in honor of the Red Army created after the revolution. The new Red Army completely renounced continuity with the old pre-revolutionary army. Shoulder straps and titles were abolished, and the institution of commissars appeared.

Only years later did the Soviet army begin to vaguely resemble the pre-revolutionary one.

In pre-Petrine times, the military class was the Streltsy, who spent their entire lives in public service. They were the most trained and almost professional troops. In peacetime, they lived on land that was granted to them for their service (but lost it if for some reason they left the service and did not pass it on), and performed a lot of other duties. The archers were supposed to maintain order and participate in putting out fires.

In the event of a serious war, when a large army was required, a limited recruitment was carried out from among the tax-paying classes.

The service of the archers was for life and was inherited. Theoretically, it was possible to resign, but to do this you had to either find someone to replace you or earn it through diligent service.

Shackles for the conscript

A regular army appeared in Russia under Peter I. Wanting to create a regular army on a European model, the tsar issued a decree on conscription. From now on, people were recruited into the army not for individual wars, but for permanent service. Recruitment was universal, that is, absolutely all classes were subject to it.

At the same time, the nobles found themselves in the most disadvantageous position. Full service was provided for them, although they almost always served in officer positions.

Peasants and townspeople recruited only a few people from the community. On average, only one man out of a hundred was recruited. Already in the 19th century, the entire territory of the country was divided into two geographical stripes, from each of which 5 recruits per thousand men were recruited every two years. In force majeure situations, an emergency recruitment could be declared - 10 or more people per thousand men.

The community determined who to recruit. And in the case of serfs, as a rule, the landowner decided. Much later, towards the end of the existence of the recruitment system, it was decided to draw lots between candidate recruits.

There was no conscription age as such, but, as a rule, men between the ages of 20 and 30 became recruits.

It is very interesting that the first regiments in the regular army were named after the names of their commanders. If the commander died or left, the name of the regiment had to change in accordance with the name of the new one. However, fearing the confusion that such a system invariably generated, it was decided to replace the names of the regiments in accordance with Russian localities.

Being recruited was perhaps the most significant event in a person’s life. After all, this practically guaranteed that he would leave his home forever and never see his family again.

In the first years of the existence of the recruitment system under Peter, escapes of recruits were so frequent and widespread that on the way to the “recruitment stations”, which simultaneously played the role of assembly points and “training”, the recruits were accompanied by escort teams, and they themselves were shackled at night. Later, instead of shackles, recruits began to get a tattoo - a small cross on the back of the hand.

A curious feature of Peter's army was the existence of the so-called. full money - compensation paid to officers and soldiers for the hardships they endured while in enemy captivity. The reward differed depending on the enemy country. For being a prisoner of war in European countries, compensation was half as much as for captivity in the non-Christian Ottoman Empire. In the 1860s, this practice was abolished due to concerns that soldiers would not show due diligence on the battlefield and would be more likely to surrender.

Since the time of Peter the Great, the army has widely practiced paying bonuses not only for individual feats in battle, but also for victories in important battles. Peter ordered to reward each participant in the Battle of Poltava. Later, during the Seven Years' War, for victory in the battle of Kunersdorf, all lower ranks who participated in it received a bonus in the form of a six-month salary. After the expulsion of Napoleon's army from Russian territory in the Patriotic War of 1812, all army ranks, without exception, received a bonus also in the amount of six months' salary.

No cronyism

Throughout the 18th century, the conditions of service for both soldiers and officers were gradually relaxed. Peter was faced with an extremely difficult task - to literally create a combat-ready regular army from scratch. We had to act by trial and error. The tsar sought to personally control many things, in particular, almost until his death, he personally approved every officer appointment in the army and vigilantly ensured that connections, both family and friendly, were not used. The title could be obtained solely on one's own merits.

In addition, Peter's army became a real social elevator. Approximately a third of the officer corps of the army of Peter the Great's times were made up of ordinary soldiers who had risen to the top. All of them received hereditary nobility.

After Peter's death, a gradual easing of service conditions began. The nobles received the right to exempt one person from the family from service so that they would have someone to manage the estate. Then their period of compulsory service was reduced to 25 years.

Under Empress Catherine II, nobles received the right not to serve at all. However, most of the nobility were landless or small-scale and continued to serve, which was the main source of income for these nobles.

A number of categories of the population were exempted from conscription. In particular, honorary citizens - the urban stratum somewhere between ordinary townspeople and nobles - were not subject to it. Representatives of the clergy and merchants were also exempted from conscription duties.

Anyone who wanted to (even serfs) could quite legally buy their way out of service, even if they were subject to it. Instead, they had to either purchase a very expensive recruiting card, issued in exchange for contributing a significant sum to the treasury, or find another recruit in their place, for example, promising a reward to anyone who wanted it.

"Rear Rats"

After lifelong service was abolished, the question arose of how to find a place in society for people who spent most of their adult life away from society, in a closed army system.

In Peter's times such a question did not arise. If a soldier was still capable of at least some kind of work, they found a use for him somewhere in the rear; as a rule, he was sent to train new recruits; at worst, he became a watchman. He was still in the army and receiving a salary. In case of decrepitude or severe injuries, soldiers were sent to the care of monasteries, where they received a certain allowance from the state. At the beginning of the 18th century, Peter I issued a special decree, according to which all monasteries had to equip almshouses for soldiers.

During the time of Catherine II, the state took over the care of the needy, including old soldiers, instead of the church. All monastic almshouses were dissolved, in return the church paid the state certain amounts, to which were added government funds, for which there was an Order of Public Charity, which was in charge of all social concerns.

All soldiers injured in service were entitled to a pension, regardless of their length of service. Upon leaving the army, they were provided with a large one-time payment for building a house and a small pension.

The reduction of service life to 25 years has led to a sharp increase in the number of disabled people. In modern Russian, this word means a person with disabilities, but in those days any retired soldiers were called disabled, regardless of whether they had injuries or not.

Under Paul, special disabled companies were formed. With these words, the modern imagination pictures a bunch of unfortunate cripples and decrepit old people, but in fact only healthy people served in such companies. They were staffed either by veterans of combat service who were close to the end of their service life, but at the same time healthy, or by those who, due to some illness, became unfit for combat service, or by those transferred from the active army for any disciplinary offenses.

Such companies were on duty at city outposts, guarded prisons and other important facilities, and escorted convicts. Later, on the basis of some disabled companies, escorts appeared.

A soldier who served his entire term of service could do whatever he wanted after leaving the army. He could choose any place of residence and engage in any type of activity. Even if he was called up as a serf, after his service he became a free man. As an incentive, retired soldiers were completely exempt from taxes.

Almost all retired soldiers settled in cities. It was much easier for them to find work there. As a rule, they became watchmen, constables or “uncles” for boys from noble families.

Soldiers rarely returned to the village. Over the course of a quarter of a century, people managed to forget him in his native land, and it was very difficult for him to once again adapt to peasant labor and the rhythm of life. Apart from this, there was practically nothing to do in the village.

Beginning with Catherine's times, special homes for the disabled began to appear in provincial cities, where retired soldiers unable to provide for themselves could live on full board and receive care. The first such house, called Kamennoostrovsky, appeared in 1778 on the initiative of Tsarevich Pavel.

In general, Pavel was very fond of soldiers and the army, so after becoming emperor he ordered the Chesme Palace, one of the imperial travel palaces, to be converted into a home for the disabled. However, during Pavel’s lifetime this could not be done due to problems with the water supply, and only two decades later it opened its doors to veterans of the Patriotic War of 1812.

Retired soldiers became one of the first categories of people to receive the right to a state pension. Soldiers' widows and young children also received the right to it if the head of the family died during service.

"Soldiers" and their children

Soldiers were not forbidden to marry, including during service, with the permission of the commander. Soldiers' wives and their future children were included in a special category of soldiers' children and soldiers' wives. As a rule, most of the soldiers' wives got married even before their chosen ones entered the army.

"Soldiers" after their husband's conscription for service automatically became personally free, even if they had previously been serfs. At first, recruits were allowed to take their family with them into service, but later this rule was abolished and the recruits' families were only allowed to join them after they had served for some time.

All male children automatically fell into a special category of soldiers' children. In fact, from birth they were under the jurisdiction of the military department. They were the only category of children in the Russian Empire who were legally obliged to study. After studying in regimental schools, “soldiers’ children” (from the 19th century they began to be called cantonists) served in the military department. Thanks to the education they received, they did not very often become ordinary soldiers, as a rule, having non-commissioned officer positions or serving in non-combatant specialties.

In the first years of its existence, the regular army usually lived in field camps in the summer, and in the cold season went to winter quarters - billeting in villages and villages. Huts for housing were provided to them by local residents as part of the housing obligation. This system led to frequent conflicts. Therefore, from the mid-18th century, special areas began to emerge in cities - soldiers' settlements.

Each such settlement had an infirmary, a church and a bathhouse. The construction of such settlements was quite expensive, so not all regiments received separate settlements. In parallel with this system, the old billet, which was used during military campaigns, continued to function.

The barracks we are accustomed to appeared at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries, and at first only in large cities.

By call

Throughout the 19th century, the service life of recruits was repeatedly reduced: first to 20 years, then to 15 and finally to 10. Emperor Alexander II carried out a large-scale military reform in the 70s: conscription was replaced by universal military service.

However, the word “universal” should not be misleading. It was universal in the USSR and is in modern Russia, but then not everyone served. With the transition to the new system, it turned out that there were several times more potential conscripts than the needs of the army required, so not every healthy young man served, but only the one who drew the lot.

It happened like this: the conscripts cast lots (pulled pieces of paper with numbers from a box). According to its results, some of the conscripts were sent to the active army, and those who did not draw lots were enlisted in the militia. This meant that they would not serve in the army, but could be mobilized in case of war.

The conscription age was somewhat different from the modern one; one could not be drafted into the army before the age of 21 and after the age of 43. The conscription campaign took place once a year, after the completion of field work - from October 1 to November 1.

All classes were subject to conscription, with the exception of the clergy and Cossacks. The service life was 6 years, but later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was reduced to three years for infantry and artillery (in other branches of the military they served for four years, in the navy for five years). At the same time, those who were completely illiterate served a full term, those who graduated from a simple rural parochial or zemstvo school served for four years, and those who had a higher education served for a year and a half.

In addition, there was a very extensive system of deferments, including those based on property status. In general, the only son in the family, the grandson of a grandfather and grandmother who had no other able-bodied descendants, a brother who had younger brothers and sisters without parents (that is, the eldest in a family of orphans), as well as university teachers were not subject to conscription.

A deferment on property status for several years was provided to business owners and migrant peasants to organize their affairs, as well as to students of educational institutions. Part of the foreign (i.e., non-Christian) population of the Caucasus, Central Asia and Siberia, as well as the Russian population of Kamchatka and Sakhalin, were not subject to conscription.

They tried to recruit regiments on a territorial basis, so that conscripts from the same region would serve together. It was believed that the joint service of fellow countrymen would strengthen cohesion and military brotherhood.

The army of Peter the Great became a difficult test for society. Unprecedented conditions of service, lifelong service, separation from their native land - all this was unusual and difficult for the recruits. However, in Peter’s times this was partly compensated for by excellent working social elevators. Some of Peter's first recruits laid the foundation for noble military dynasties. Subsequently, with the reduction of service life, the army became the main instrument for the liberation of peasants from serfdom. With the transition to the conscription system, the army turned into a real school of life. The length of service was no longer so long, and conscripts returned from the army as literate people.

In our special issue “Professional” (“Red Star” No. 228) we talked about the fact that the regular Russian army not only began its formation in Peter’s times on a contract basis, but also then, in all subsequent reigns - from Catherine I to Nicholas II - partly consisted of “lower ranks” who voluntarily entered the service, that is, soldiers and non-commissioned officers. The system of manning the armed forces was changing: there was conscription, there was all-class conscription, but “contract soldiers,” in modern language, still remained in the army... Today we will continue the story on the same topic and try to understand what benefits these same ones brought to the army “contract soldiers” were not of noble rank and why they themselves voluntarily served in its ranks.

About the soldiers who were old enough to be grandfathers to officers

So-called“recruitment” existed from 1699 (by the way, the word “recruit” itself was introduced into use only in 1705) and before, in accordance with the manifesto of Alexander II, Russia switched to “all-class military service” in 1874.

It is known that people were recruited from the age of 20, and not from the age of 18, as we were called up in the 20th century, which, you see, represents a certain difference. Then the same age - 20 years - remained during the transition to conscription service... It would also not be superfluous to say that people under the age of 35 were taken as recruits, which means that with a twenty-five-year service life a soldier could, as it was said then , “pull the strap” until a very respectable age - until the seventh decade. However, in the “era of the Napoleonic Wars” they even began to hire 40-year-olds... As a result, the army, or rather its soldier composition, grew old inexorably and inevitably.

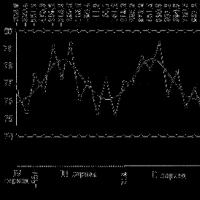

But the officer corps was not only young, but rather, simply young. Let's take Dmitry Tselorungo's book “Officers of the Russian Army - Participants in the Battle of Borodino” and open a table that shows the age level of these officers. It analyzed data for 2,074 people, and from this figure calculations were made that were quite consistent with the “arithmetic average” for the entire Russian army of 1812.

The main age of the officers who fought at Borodino was from 21 to 25 years old - 782 people, or 37.7 percent. 421 people, or 20.3 percent of all officers, were between 26 and 30 years old. Overall, officers aged 21 to 30 accounted for almost 60 percent of the total. Moreover, it should be added that 276 people - 13.3 percent - were aged 19-20 years; 88 people – 4.2 percent – are 17-18 years old; 18 people - 0.9 percent - were 15-16 years old, and another 0.05 percent was a single young officer 14 years old. By the way, under Borodin there was also only one officer over the age of 55... In general, almost 80 percent of the commanders in the army were between the ages of 14 and 30, and just over twenty of those who were over 30. They were led - let us remember the famous lines of poetry - by “young generals of yesteryear”: Count Miloradovich, who commanded the troops of the right flank at Borodin, was 40, brigade commander Tuchkov 4th was 35, and chief of artillery of the 1st Army, Count Kutaisov, was 28...

So imagine a completely ordinary picture: a 17-year-old warrant officer, a young man at the age of our modern Suvorov senior student, goes out in front of the formation of his platoon. Standing in front of him are men of 40 to 50 years old. The officer greets them with the exclamation “Hello, guys!”, and the gray-haired “guys” unanimously shout back, “We wish you good health, your honor!” “Come on, come here! - the ensign calls some 60-year-old grandfather out of formation. “Explain to me, brother...”

All this was as it should be: the form of greeting - “guys”, and the liberal-condescending address to the soldier “brother”, and the conversation with the lower rank, a representative of the “vile class”, exclusively on a personal basis. The latter, however, has come down to our times - some bosses see any of their subordinates as a “lower rank”...

By the way, the memory of those morals was preserved both in old soldiers’ songs - “Soldiers, brave boys!”, and in literature - “Guys, isn’t Moscow behind us?”

Of course, much can be explained by the peculiarities of serfdom, that distant time when a soldier saw in an officer primarily a representative of the upper class, to whom he was always obliged to obey unquestioningly. But still, was it so easy for yesterday’s graduates of cadet corps, recent cadets who learned the basics of practical military science here in the regiment under the leadership of “uncles” - experienced soldiers, to command elderly soldiers who sometimes “broke” more than one campaign?

Here, by the way, although the time is somewhat different - already the very end of the 19th century - but a very accurate description of a similar situation, taken from the book of Count Alexei Alekseevich Ignatiev “Fifty Years in the Army”:

“I come to class...

“Command,” I say to the non-commissioned officer.

He clearly pronounces the command, upon which my students quickly scatter around the hall in a checkerboard pattern.

- Protect your right cheek, stab to the left, cut down to the right!

The whistle of checkers in the air, and again - complete silence.

What should I teach here? God willing, I wish I could remember all this myself for the review, where I will have to command.

“It’s not very clean,” the sergeant tells me intelligibly, “they do it very badly there in the third platoon.”

I’m silent because the soldiers do everything better than I do.”

Meanwhile, Count Ignatiev was not one of the “regimental cadets”, but was educated in the Corps of Pages, one of the best military educational institutions in Russia...

It is clear that between the two categories of military personnel - officers and soldiers - there had to be some kind of, let's say, connecting link. One can also guess that sergeants - non-commissioned officers at that time - should have been such.

Yes, theoretically this is true. But we have the sad experience of the Soviet Army, where sergeants were often called “private soldiers with badges” and they always complained that officers had to replace them... Moreover, if representatives of a socially united society served in the Soviet Army, then in the Russian Army , as already said, officers represented one class, soldiers another. And although today the “class approach” is not in fashion, however, honestly, we should not forget about “class contradictions” and, by the way, about “class hatred”. It is clear that in the depths of his soul the peasant did not particularly favor the landowner-nobleman - and, I think, even at a time when one of them wore shoulder straps, and the other wore epaulettes. The exception, of course, is the year 1812, when the fate of the Fatherland was decided. It is known that this time became an era of unprecedented unity of all layers of Russian society, and those who found themselves at the theater of war - soldiers, officers and generals - then equally shared the march loads, stale crackers and enemy bullets... But, fortunately or unfortunately, this did not happen too often in our history.

But in peacetime, as well as during some local military campaigns, there was no trace of such closeness in the army. So is it worth clarifying that not every non-commissioned officer sought to curry favor with the officers, in one sense or another to “betray” his comrades. In the name of what? There was, of course, a material interest: if during the reign of Emperor Paul I in the Life Guards Hussar Regiment, a combat hussar received 22 rubles a year, then a non-commissioned officer received 60, almost three times more. But in our lives, human relationships are not always determined by money. Therefore, a normal, let’s say, non-commissioned officer more often found himself on the soldier’s side, trying in every possible way to cover up his sins and protect him from the command... It was, of course, different, as Count Ignatiev again testifies: “Latvians are the most serviceable soldiers , - bad riders, but people with a strong will, turned into fierce enemies of the soldiers as soon as they received non-commissioned officer braid.”

However, the role of that very connecting link, and maybe even some kind of “layer”, was, of course, not they, but, again, “contract soldiers” - that is, the lower ranks who served under the contract...

“Where should the soldier go now?”

Before 1793 Russian soldier served for life. Then - twenty-five years. It is known that Emperor Alexander Pavlovich, at the end of his stormy and controversial quarter-century reign, wearily complained to those close to him: “Even a soldier, after twenty-five years of service, is being released to retire...” This period remained in the memory of posterity, in which it seemed to “extend” to everything XIX century.

And here is what Colonel Pavel Ivanovich Pestel, the head of the secret Southern Society, wrote: “The term for service, determined at 25 years, is so long by any measure that few soldiers go through it and stand it, and therefore, from infancy, they get used to looking at military service as a severe misfortune and almost as a decisive sentence to death "

What is said about the “sentence to death” is quite fair. Without even touching on participation in hostilities, let us clarify that, firstly, life expectancy in Russia in the century before last was still shorter than now, and, as we said, they could be recruited even at a fair age. Secondly, the army service of that time had its own specifics. “Kill nine, train the tenth!” - Grand Duke and Tsarevich Konstantin Pavlovich, a veteran of the Italian and Swiss campaigns, used to say. He, who on April 19, 1799 personally led a company in an attack near Basignano, distinguished himself at Tidone, Trebbia and Novi, showed considerable courage in the Alpine Mountains, for which he was awarded by his father Emperor Paul I the diamond insignia of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, “became famous” later for such “pearls” as “war spoils the army” and “these people don’t know how to do anything except fight!”

« Recruit

- a recruit, a newcomer to military service, who has entered the ranks of soldiers, privates, by conscription or for hire.”

(Explanatory dictionary of the living Great Russian language.)

Although this should not be surprising: after all, in the army, especially in the guard regiments, the imperial family primarily saw the support and protection of the throne from all sorts of enemies, and Russian history has quite convincingly proven that external danger for our sovereigns was much less dangerous than internal. Whatever you say, not one of them was killed by the interventionists... That is why the soldiers were trained for years, so that at any moment, without hesitation, they would be ready to fulfill the highest will.

It is clear that in a quarter of a century almost any man could be turned into a capable soldier. Moreover, they took into the army, and even more so into the guard, not just anyone, but in accordance with certain rules.

The recruit who came to the service was taught not only the basics of military art, but also the rules of behavior, one might even say, “noble manners.” Thus, in the “Instructions for the Colonel’s Cavalry Regiment” of 1766 it is said, “so that the peasant’s mean habit, evasion, grimace, scratching during conversation would be completely exterminated from him”. The aforementioned Tsarevich Konstantin demanded “so that people would disdain to sound like peasants, ... so that every person would be able to speak decently, intelligently and without shouting, would answer his superior without being timid or insolent in front of him, would always have the appearance of a soldier with proper posture, for knowing his business, He has nothing to fear..."

Quite soon - under the influence of persuasion and everyday drill, as well as, if necessary, a fist and a rod - the recruit turned into a completely different person. And not only externally: he was already becoming different in essence, because the soldier was emerging from serfdom, and long years of service completely separated him from his family, homeland, and usual way of life. That’s why, after serving, the veteran faced the problem of where to go, how to live next? By releasing him “cleanly,” the state obliged the retired soldier to “shave his beard” and not engage in begging, and somehow no one cared about anything else...

Retired soldiers had to make their own lives. Some went to the almshouse in old age, some were assigned to be janitors or doormen, some to the city service - depending on age, strength and health...  By the way, It is worth noting that throughout the 19th century, the number of years of military service according to conscription gradually decreased - which means that younger, healthier people retired. Thus, in the second half of the reign of Alexander I, his service in the guard was reduced by three years - to 22 years. But the Blessed One, as Emperor Alexander Pavlovich was officially called, who always looked abroad and was very favorable towards the Poles and Balts, already in 1816 reduced the period of military service in the Kingdom of Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire, to 16 years...

By the way, It is worth noting that throughout the 19th century, the number of years of military service according to conscription gradually decreased - which means that younger, healthier people retired. Thus, in the second half of the reign of Alexander I, his service in the guard was reduced by three years - to 22 years. But the Blessed One, as Emperor Alexander Pavlovich was officially called, who always looked abroad and was very favorable towards the Poles and Balts, already in 1816 reduced the period of military service in the Kingdom of Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire, to 16 years...

In Russia itself, this was achieved only at the end of the reign of his brother, Nicholas I. And then only in several stages - after reductions in 1827, 1829, 1831 and other years - the service life by 1851 gradually reached 15 years.

By the way, there were also “targeted” reductions. IN “The History of the Life Guards of the Izmailovsky Regiment,” for example, states that after the suppression of the rebellion of 1831, “a command was issued that again showed the love, care and gratitude of the monarch to the pacifiers of Poland. This command shortened two years of service for troops who were on the campaign... Those wishing to remain in the service were ordered to receive an additional one and a half salary and, after serving a five-year period from the date of refusal to resign, to turn all this salary into a pension, regardless of the specific state pension.”

« Recruitment set- the old way of recruiting people for our army; began in 1699 and continued until 1874... Recruits were supplied by tax-paying classes. At first, recruitments were random, as needed. They became annual in 1831, with the publication of the recruiting regulations.”

(Small Encyclopedic Dictionary. Brockhaus - Efron.)

And since in the conditions of Europe at that time, pacified after the Napoleonic storms, there was no need for extraordinary recruitment, then mostly people 20-25 years old were taken into the service. It turned out that by the age of 40 the soldier had already finished his service - it seemed that it was still possible to start a new life, but not everyone wanted it, not everyone liked it... So some decided to completely connect their lives with the army, with which they became close over many years of service.

I would be glad to serve!

Let's take the book “Life Hussars” published last year by Military Publishing House - the history of the Life Guards of His Imperial Majesty the Hussar Regiment - and we will select the following information from there:

“Until 1826... a private who wanted to continue serving after the end of his legal term received a salary increased by a six-month salary...

On August 22, 1826, on the day of the sacred coronation, the sovereign emperor was pleased... to dismiss the lower ranks who had served in the guard for 20 years (23 years in the army)... As for the lower ranks who wished to remain in service even after the appointed time, then... their salary increase was supposed to be increased not only by half salary, but by an additional full salary, that is, for privates who voluntarily remained in the service, their salary was increased two and a half times. But this was not the end of the highest benefits and advantages granted to them.

Those of them who, after refusing to resign, served for another five years, their salary, increased by two and a half times, is supposed to be converted into a pension upon death, and they receive this pension regardless of the funds that are provided to them by the insignia of the Military Order and the Holy Anna."

By the way, as a sign of special distinction, such “contract” warriors received a gold braid patch on their left sleeve, and every five years they were given another patch.

“On July 1, 1829, it was ordered to lower ranks who had served in the rank of non-commissioned officer for 10 years (in the army for 12 years) and, after passing the established exam, refused promotion to officers, to make a payment in the service of two-thirds of the cornet salary and after they had served for five years after Therefore, this salary will be converted into a lifelong pension.”

We already talked about why not all non-commissioned officers wanted to receive chief officer epaulettes and with them the dignity of nobility...

On March 26, 1843, the method of promoting non-commissioned officers to chief officers was changed: all those who passed the exam were divided into two categories based on its results. “Non-commissioned officers who passed the first-class examination in the program received the right to be promoted to army regiments, and for refusing it they enjoyed the following advantages: they had a silver lanyard, a braided sleeve patch, were exempt from corporal punishment and demotion to the rank and file without court... and also to receive two-thirds of the cornet's salary as a pension after service for five years from the date of assignment of this salary.

Non-commissioned officers of the second category, that is, those who passed the weakest examination, were not promoted to officers, but if they wished to remain in the service, they were assigned one-third of the cornet salary, which, after five years of service, was converted into a pension, and at the same time all other advantages were presented non-commissioned officers of the first category, with the exception of only a silver lanyard..."

Unfortunately, A modern military man, wearing our completely impersonal, “non-national” uniform, has no idea how much certain details of ancient uniforms meant. For example, a silver lanyard on a saber or sword was an honorary accessory of an officer’s rank - it was not without reason that after the Battle of Austerlitz on November 20, 1805, when the Novgorod Musketeer Regiment faltered, its officers were deprived of such a distinction. So the lower rank, awarded the silver lanyard, was close to the officers, who now had to address him as “you.”

All of the listed benefits and features of the service of the then “contract soldiers” - and for them there were their own rules for placement and organization of life - not only radically separated them from ordinary soldiers and non-commissioned officers, but also to a certain extent changed the psychology of both themselves and their colleagues in relation to them. These people really had something to lose, and they categorically did not want to return to the original one. And not only because of what they directly gained from the service, but also because of their attitude towards it. People who did not like service did not remain to serve beyond their term and did not refuse the officer rank, which gave the right to retire... But here there was truly selfless love, based on the awareness that a military man is superior to a civilian in all respects. That’s how it was, that’s how we were raised!

It is clear that no one would have dared to call such a “bourbon” a “soldier with stripes,” as the toughest representatives of the non-commissioned, as well as the officer, class were called in those days. This was no longer a soldier, although not an officer at all - he was a representative of precisely that extremely necessary connecting link, which, in the words of one German military theorist, was “the backbone of the army.”

However, it is known that “contract soldiers” in the army of that time performed the duties not only of junior commanders, but also of various kinds of non-combatant specialists, which was also very valuable. An absolutely amazing episode was described by the former cavalry guard Count Ignatiev - I will give his story in abbreviation...

Death of a Stoker

“On one regiment duty, the following happened: in the evening... the non-commissioned officer on duty on a non-combatant team came running and, with excitement in his voice, reported that “Alexander Ivanovich died.”

Everyone, from the private to the regiment commander, called Alexander Ivanovich the old bearded sergeant major who stood for hours next to the orderly at the gate, regularly saluting everyone passing by.

Where did Alexander Ivanovich come to us from? It turned out that still... at the beginning

In the 1870s, the stoves in the regiment smoked incredibly, and no one could cope with them; Once the military district sent a specialist stove maker from the Jewish cantonists, Oshansky, to the regiment. With him, the stoves burned properly, but without him they smoked. Everyone knew this for sure and, bypassing all the rules and laws, they detained Oshansky in the regiment, giving him a uniform, titles, medals and distinctions for long-term “unblemished service”... His sons also served in long-term service, one as a trumpeter, the other as a clerk , the third - a tailor...

I could never have imagined what happened in the next few hours. Luxurious sleighs and carriages drove up to the regimental gates, from which elegant, elegant ladies in furs and respectable gentlemen in top hats emerged; they all made their way to the basement, where the body of Alexander Ivanovich lay. It turned out - and this could not have occurred to any of us - that Sergeant Major Oshansky had been at the head of the St. Petersburg Jewish community for many years. The next morning the body was carried out... In addition to all Jewish St. Petersburg, not only all the available officers of the regiment came here, but also many old cavalry guards, led by all the former commanders of the regiment.”

The given fragment indicates that, firstly, in former times even very respected people entered the “contract service” and, secondly, that in the regiments their “contract soldiers” were truly valued...

However, we always say “in regiments,” whereas in the 19th century the Russian army had at least one separate military unit, fully staffed by “contract soldiers.”

Eighty years in service

In issue 19 of the magazine“Bulletin of the Military Clergy” for 1892, I found an absolutely amazing biography of the Russian “contract soldier” Vasily Nikolaevich Kochetkov, born in 1785.

In May 1811 - respectively 26 years old - he was taken into military service and assigned to the famous Life Grenadier Regiment, which was soon assigned to the guard and named the Life Guard Grenadier. In 1812, taking part in rearguard battles, this regiment retreated to Mozhaisk, and Kochetkov fought in its ranks at Borodino, and then at Leipzig, taking Paris. Then there was the Turkish War of 1827-1828, where the life grenadiers seemed to justify themselves for their presence among the rebel troops on Senate Square on December 14, 1825... After that, the Russian guard pretty much beat up the Polish rebels on the Grokhovsky field and near the town of Ostroleka, and in In 1831, Guards grenadiers took part in the capture of Warsaw.

By this time, Kochetkov had just served 20 years, having refused the officer rank - therefore, he was a non-commissioned officer, but he did not “outright” leave, but stayed for extra-long term. Moreover, the old grenadier decided to continue his service not on the St. Petersburg parquets, but in the Caucasian Corps, where he spent five years in battle - and for ten months he was captured by robbers. Vasily Nikolayevich returned from the Caucasus in 1847; he was then already “sixty-odd”; it was time to think about retirement. And he really finished his service - however, only after he visited Hungary in 1849, where the troops of Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich helped the Austrian allies restore order...

Probably, the traces of the grenadier Kochetkov would have been lost, but the events of the Crimean War again called the veteran into service. The old man reached Sevastopol, joined the ranks of those fighting for the city, and even took part in the forays of the besieged garrison. When he returned to St. Petersburg, Emperor Alexander II enlisted the old soldier in the Life Guards Dragoon Regiment, where Kochetkov served for six years, and after that he entered the Palace Grenadier Company - that very special unit where all soldiers served voluntarily... Company served in the Winter Palace, and court service clearly did not appeal to the veteran, who soon went to Central Asia, where he fought under the banners of the glorious general Skobelev, recapturing Samarkand and Khiva... He returned to his company only in 1873 - note, 88 years old from birth. True, he again did not stay here for long, because three years later he volunteered for the active army beyond the Danube and, it’s just scary to think, he fought on Shipka - these are the steepest mountains, completely unimaginable conditions. But the veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812 was able to cope with everything...

Having finished the war, Kochetkov again returned to the Palace Grenadier company, served in it for another 13 years, and then decided to return to his native land. But it didn’t come true... As stated in “Bulletin of the Military Clergy,” “death overtook the poor soldier completely unexpectedly, at a time when he, having received his retirement, was returning to his homeland, rushing to see his relatives and live in peace after a long service.”

Perhaps no one else had a greater combat path than this “contract soldier” grenadier.

Palace Grenadiers

Dvortsov Company The grenadier was formed in 1827 and performed honor guard duty in the Winter Palace. At first, it included guards soldiers who went through the entire Patriotic War - first from Neman to Borodino, then from Tarutino to Paris. If the guards, dressed up from the guard regiments, protected the sovereign, then the main task of the palace grenadiers was to maintain order and keep an eye on the cunning court servants - footmen, stokers and other brethren. If in the 20th century they loudly shouted about “civilian control” over the army, then in the 19th century they understood that it would be safer and calmer when disciplined and honest military personnel looked after civilian dodgers...

“Volunteers are persons with educational qualifications who entered voluntarily, without drawing lots, for active military service in the lower ranks. The voluntary service of those who volunteer is based not on a contract, but on the law; it is the same military service, but only with a modification of the nature of its implementation.”

(Military Encyclopedia. 1912).

At first, old-timers were selected for the company, and later they began to recruit those who had fully served their term, that is, “contract soldiers.” At the behest of Emperor Nicholas I, he immediately determined that the salary was very good: non-commissioned officers equal in rank to army warrant officers - 700 rubles per year, grenadiers of the first article - 350, grenadiers of the second article - 300. A non-commissioned officer of the palace grenadiers was actually an officer , so he received an officer’s salary. Such obscenity, that even a “contract” soldier of even the most “elite” unit received a salary greater than an officer’s, has never happened in the Russian army. By the way, in the company guarding the Winter Palace, not only were “contract” soldiers serving, but all its officers were promoted from ordinary soldiers, they began their service as the same recruits as their subordinates!

It can be understood that Emperor Nicholas I, who founded this company, had a special trust in it, which the palace grenadiers fully justified. Suffice it to recall the fire in the Winter Palace on December 17, 1837, when they, together with the Preobrazhensky guards, carried out portraits of generals from the Military Gallery of 1812 and the most valuable palace property.

After all, they were always guided by what is considered the most expensive here, what requires special attention... By the way, here it is worth remembering how Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich appeared in the middle of the burning hall and, seeing that the grenadiers, straining themselves, were dragging a huge Venetian mirror, told them: “No need, guys, leave it! Save yourself!” - “Your Majesty! – one of the soldiers objected. “It’s impossible, it costs so much money!” The king calmly broke the mirror with a candelabra: “Now leave it!”

Two of the grenadiers - non-commissioned officer Alexander Ivanov and Savely Pavlukhin - died then in a burning building... Real army service is never easy, it is always fraught with some potential danger. In previous times, they tried to compensate for this “risk factor” at least financially...

...That's basically it and everything that I would like to tell about the history of “contract service” in Russia. As you can see, it was not something far-fetched or artificial, and, provided its organization was comprehensively thought out, it brought considerable benefits to the army and to Russia.

However, it would be worth recalling that never – even at the very beginning of its history – our regular army was purely “contract”. “Contract soldiers”, no matter how they were called, were an elite part of the “lower ranks”, they were a reliable link between officers, command staff and the rank and file, non-commissioned officers, the “backbone” of that very Russian army that fought bravely at Poltava and Borodino, defended Sevastopol, crossed the Balkans and, thanks to the mediocrity of the highest state leadership, disappeared undefeated on the fields of the First World War.

In the pictures: Unknown artist. Palace Grenadier.

V. SHIRKOV. Extra-conscript private of the Yamburg Uhlan Regiment. 1845.

How was conscription carried out into the army of Imperial Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. Who was subject to it? Those who had conscription benefits, monetary rewards for military personnel. Collection of statistics.

"Of all the subjects of the Russian Empire who had reached conscription age (20 years), about 1/3 - 450,000 out of 1,300,000 people - were called up for active military service by lot. The rest were enlisted in the militia, where they were trained at short training camps.

Call once a year - from September 15 or October 1 to November 1 or 15 - depending on the timing of the harvest.

Duration of service in the ground forces: 3 years in infantry and artillery (except cavalry); 4 years in other branches of the military.

After this, they were enlisted in the reserves, which were called up only in case of war. The reserve period is 13-15 years.

In the navy, conscript service is 5 years and 5 years in reserve.

The following were not subject to conscription for military service:

Residents of remote places: Kamchatka, Sakhalin, some areas of the Yakut region, Yenisei province, Tomsk, Tobolsk provinces, as well as Finland. Foreigners of Siberia (except for Koreans and Bukhtarminians), Astrakhan, Arkhangelsk provinces, Steppe Territory, Transcaspian region and the population of Turkestan. Some foreigners of the Caucasus region and Stavropol province (Kurds, Abkhazians, Kalmyks, Nogais, etc.) pay a cash tax instead of military service; Finland deducts 12 million marks from the treasury annually. Persons of Jewish nationality are not allowed into the fleet.

Benefits based on marital status:

Not subject to conscription:

1. The only son in the family.

2. The only son capable of working with an incapacitated father or widowed mother.

3. The only brother for orphans under 16 years of age.

4. The only grandchild with an incapacitated grandmother and grandfather without adult sons.

5. Illegitimate son with his mother (in his care).

6. Lonely widower with children.

Subject to conscription in the event of a shortage of suitable conscripts:

1. The only son capable of working, with an elderly father (50 years old).

2. Following a brother who died or went missing in service.

3. Following his brother, still serving in the army.

Deferments and benefits for education:

Receive a deferment from conscription:

up to 30 years of age, government scholarship holders preparing to take up scientific and educational positions, after which they are completely released;

up to 28 years of age, students of higher educational institutions with a 5-year course;

up to 27 years of age in higher education institutions with a 4-year course;

up to 24 years of age, students of secondary educational institutions;

students of all schools, upon request and agreement of ministers;

for 5 years - candidates for preaching of Evangelical Lutherans.

(In wartime, persons who have the above benefits are taken into service until the end of the course according to the Highest permission).

Reduction of active service periods:

Persons with higher, secondary (1st rank) and lower (2nd rank) education serve in the military for 3 years;

Persons who have passed the exam for reserve warrant officer serve for 2 years;

doctors and pharmacists serve in the ranks for 4 months, and then serve in their specialty for 1 year 8 months

in the navy, persons with an 11th grade education (lower educational institutions) serve for 2 years and are in the reserve for 7 years.

Benefits based on professional affiliation

The following are exempt from military service:

- Christian and Muslim clergy (muezzins are at least 22 years old).

- Scientists (academicians, adjuncts, professors, lecturers with assistants, lecturers of oriental languages, associate professors and private assistant professors).

- Artists of the Academy of Arts sent abroad for improvement.

- Some academic and educational officials.

Privileges:

- Teachers and academic and educational officials serve for 2 years, and under the temporary 5-year position from December 1, 1912 - 1 year.

- Paramedics who have graduated from special naval and military schools serve for 1.5 years.

- Graduates of the schools for soldiers' children of the Guard troops serve for 5 years, starting from the age of 18-20.

- Technicians and pyrotechnicians of the artillery department serve for 4 years after graduation.

- Civilian seamen are given a deferment until the end of the contract (no more than a year).

- Persons with higher and secondary education are accepted into service voluntarily from the age of 17. Service life - 2 years.

Those who pass the exam for the rank of reserve officer serve for 1.5 years.

Volunteers in the navy - only with higher education - service life is 2 years.

Persons who do not have the above education can voluntarily enter the service without drawing lots, the so-called. hunters. They serve on a general basis.

Cossack conscription

(The Don Army is taken as a model; other Cossack troops serve in accordance with their traditions).

All men are required to serve without ransom or replacement on their own horses with their own equipment.

The entire army provides servicemen and militias. Servicemen are divided into 3 categories: 1 preparatory (20-21 years old) undergoes military training. II combatant (21-33 years old) is directly serving. III reserve (33-38 years old) deploys troops for war and replenishes losses. During the war, everyone serves without regard to rank.

Militia - all those capable of service, but not included in the service, form special units.

Cossacks have benefits: according to marital status (1 employee in the family, 2 or more family members are already serving); by property (fire victims who became impoverished for no reason of their own); by education (depending on education, they serve from 1 to 3 years in service).

2. Composition of the ground army

All ground forces are divided into regular, Cossack, police and militia. — the police are formed from volunteers (mostly foreigners) as needed in peacetime and wartime.

By branch, the troops consist of:

- infantry

- cavalry

- artillery

- technical troops (engineering, railway, aeronautical);

- in addition - auxiliary units (border guards, convoy units, disciplinary units, etc.).

- b) cavalry is divided into guards and army.

- 4 - cuirassiers

- 1 - dragoon

- 1 - horse grenadier

- 2 - Uhlan

- 2 - hussars

The Army Cavalry Division consists of; from 1 dragoon, 1 uhlan, 1 hussar, 1 Cossack regiment.

Guards cuirassier regiments consist of 4 squadrons, the remaining army and guards regiments consist of 6 squadrons, each of which has 4 platoons. Composition of the cavalry regiment: 1000 lower ranks with 900 horses, not counting officers. In addition to the Cossack regiments included in the regular divisions, special Cossack divisions and brigades are also formed.

3. Fleet composition

All ships are divided into 15 classes:

1. Battleships.

2. Armored cruisers.

3. Cruisers.

4. Destroyers.

5. Destroyers.

6. Minor boats.

7. Barriers.

8. Submarines.

9. Gunboats.

10. River gunboats.

11. Transports.

12. Messenger ships.

14. Training ships.

15. Port ships.

The infantry is divided into guards, grenadier and army. The division consists of 2 brigades, in the brigade there are 2 regiments. The infantry regiment consists of 4 battalions (some of 2). The battalion consists of 4 companies.

In addition, the regiments have machine gun teams, communications teams, mounted orderlies and scouts.

The total strength of the regiment in peacetime is about 1900 people.

Guards regular regiments - 10

In addition, 3 Guards Cossack regiments.

Source: Russian Suvorin calendar for 1914. St. Petersburg, 1914. P.331.

Composition of the Russian Army as of April 1912 by branch of service and departmental services (by staff/lists)

Source:Military statistical yearbook of the army for 1912. St. Petersburg, 1914. P. 26, 27, 54, 55.

Composition of army officers by education, marital status, class, age, as of April 1912

Source: Military Statistical Yearbook of the Army for 1912. St. Petersburg, 1914. P.228-230.

Composition of the lower ranks of the army by education, marital status, class, nationality and occupation before entering military service

Source:Military statistical yearbook for 1912. St. Petersburg, 1914. P.372-375.

Salary of officers and military clergy (rub. per year)

(1) - Increased salaries were assigned in remote districts, in academies, officer schools, and in the aeronautical troops.

(2)- No deductions were made from the additional money.

(3) - Additional money was given to staff officers in such a way that the total amount of salary, canteens and additional money did not exceed 2520 rubles for colonels, 2400 rubles for lieutenant colonels. in year.

(4) - In the guard, captains, staff captains, and lieutenants received a salary 1 step higher.

(5) - The military clergy received a salary increase of 1/4 of their salary for 10 and 20 years of service.

Officers were issued the so-called when transferring to a new duty station and on business trips. passing money for hiring horses.

When on various types of business trips outside the unit limits, daily allowance and ration money are issued.

Table money, in contrast to salaries and additional money, was assigned to officers not by rank, but depending on their position:

- corps commanders - 5,700 rubles.

- heads of infantry and cavalry divisions - 4200 rubles.

- heads of individual teams - 3,300 rubles.

- commanders of non-individual brigades and regiments - 2,700 rubles.

- commanders of individual battalions and artillery divisions - 1056 rubles.

- commanders of field gendarmerie squadrons - 1020 rubles.

- battery commanders - 900 rubles.

- commanders of non-individual battalions, heads of economic units in the troops, assistants of cavalry regiments - 660 rubles.

- junior staff officers of the artillery brigade department, company commanders of fortress and siege artillery - 600 rubles.

- commanders of individual sapper companies and commanders of individual hundreds - 480 rubles.

- company, squadron and hundred commanders, heads of training teams - 360 rubles.

- senior officers (one at a time) in batteries - 300 rubles.

- senior officers (except one) in artillery batteries in companies, heads of machine gun teams - 180 rubles.

- official officers in the troops - 96 rubles.

Deductions were made from salaries and table money:

- 1% per hospital

- 1.5% on medicines (regimental pharmacy)

- 1% from canteens

- 1% of salary

to pension capital

- 6% - to the emeritus fund (for increases and pensions)

- 1% of canteen money in disabled capital.

When awarding orders, an amount is paid in the amount of:

- St. Stanislaus 3 art. — 15 rub., 2 tbsp. — 30 rub.; 1 tbsp. - 120.

- St. Anne 3 art. — 20 rub.; 2 tbsp. — 35 rub.; 1 tbsp. — 150 rub.

- St. Vladimir 4 tbsp. — 40 rub.; 3 tbsp. — 45 rub.; 2 tbsp. — 225 rub.; 1 tbsp. — 450 rub.

- White eagle - 300 rub.

- St. Alexander Nevsky - 400 rubles.

- St. Andrew the First-Called - 500 rubles.

No deductions are made for other orders.

The money went into the order capital of each order and was used to help the gentlemen of this order.

Officers were given apartment money, money for the maintenance of stables, as well as money for heating and lighting apartments, depending on the location of the military unit.

The settlements of European Russia and Siberia (1) are divided into 9 categories depending on the cost of housing and fuel. The difference in payment for apartments and fuel prices between settlements of the 1st category (Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kyiv, Odessa, etc.) and 9th category (small settlements) was 200% (4 times).

Military personnel taken prisoner and who were not in the enemy's service, upon returning from captivity, receive a salary for the entire time spent in captivity, except for table money. The family of a captive has the right to receive half of his salary, and is also provided with housing money, and, if anyone is entitled, an allowance for hiring servants.

Officers serving in remote areas have the right to a salary increase depending on the length of service in these areas for every 5 years of 20-25% (depending on the location), and for every 10 years a lump sum allowance.

In pre-Petrine times, the military class was the Streltsy, who spent their entire lives in public service. They were the most trained and almost professional troops. In peacetime, they lived on land that was granted to them for their service (but lost it if for some reason they left the service and did not pass it on), and performed a lot of other duties. The archers were supposed to maintain order and participate in putting out fires.

In the event of a serious war, when a large army was required, a limited recruitment was carried out from among the tax-paying classes. The service of the archers was for life and was inherited. Theoretically, it was possible to resign, but to do this you had to either find someone to replace you or earn it through diligent service.

Shackles for the conscript

A regular army appeared in Russia under Peter I. Wanting to create a regular army on a European model, the tsar issued a decree on conscription. From now on, people were recruited into the army not for individual wars, but for permanent service. Recruitment was universal, that is, absolutely all classes were subject to it. At the same time, the nobles were in the most disadvantageous position. General service was provided for them, although they almost always served in officer positions. Peasants and townspeople recruited only a few people from the community. On average, only one man out of a hundred was recruited. Already in the 19th century, the entire territory of the country was divided into two geographical stripes, from each of which 5 recruits per thousand men were recruited every two years. In force majeure situations, an emergency recruitment could be declared - 10 or more people per thousand men. The community determined who to recruit. And in the case of serfs, as a rule, the landowner decided. Much later, towards the end of the existence of the recruiting system, it was decided to draw lots between candidates for recruits. There was no conscription age as such, but, as a rule, men between the ages of 20 and 30 became recruits. It is very interesting that the first regiments in the regular armies were named after the names of their commanders. If the commander died or left, the name of the regiment had to change in accordance with the name of the new one. However, fearing the confusion that such a system invariably generated, it was decided to replace the names of the regiments in accordance with Russian localities.

Being recruited was perhaps the most significant event in a person’s life. After all, this practically guaranteed that he would leave his home forever and never see his relatives again. In the first years of the existence of the recruitment system under Peter, escapes of recruits were such a frequent and widespread phenomenon that on the way to the “recruitment stations”, which simultaneously played the role of assembly points and "training", the recruits were accompanied by escort teams, and they themselves were shackled at night. Later, instead of shackles, recruits began to get a tattoo - a small cross on the back of the hand. A curious feature of Peter the Great’s army was the existence of the so-called. full money - compensation paid to officers and soldiers for the hardships they endured while in enemy captivity. The reward differed depending on the enemy country. For being a prisoner of war in European countries, compensation was half as much as for captivity in the non-Christian Ottoman Empire. In the 60s of the 18th century, this practice was abolished, as fears arose that soldiers would not show due diligence on the battlefield, but would more often surrender. Starting from Peter the Great’s times, the army widely practiced paying bonuses not only for individual feats in battle, but also for victories in important battles. Peter ordered to reward each participant in the Battle of Poltava. Later, during the Seven Years' War, for victory in the battle of Kunersdorf, all lower ranks who participated in it received a bonus in the form of a six-month salary. After the expulsion of Napoleon's army from Russian territory in the Patriotic War of 1812, all army ranks, without exception, received a bonus also in the amount of six months' salary.

No cronyism

Throughout the 18th century, the conditions of service for both soldiers and officers were gradually relaxed. Peter was faced with an extremely difficult task - to literally create a combat-ready regular army from scratch. We had to act by trial and error. The tsar sought to personally control many things, in particular, almost until his death, he personally approved every officer appointment in the army and vigilantly ensured that connections, both family and friendly, were not used. The title could be obtained solely on one’s own merits. In addition, Peter’s army became a real social elevator. Approximately a third of the officer corps of the army of Peter the Great's times were made up of ordinary soldiers who had risen to the top. All of them received hereditary nobility.

After Peter's death, a gradual easing of service conditions began. The nobles received the right to exempt one person from the family from service so that they would have someone to manage the estate. Then their period of compulsory service was reduced to 25 years. Under Empress Catherine II, the nobles received the right not to serve at all. However, most of the nobility were homeless or small and continued to serve, which was the main source of income for these nobles. A number of categories of the population were exempt from conscription. In particular, honorary citizens - the urban stratum somewhere between ordinary townspeople and nobles - were not subject to it. Representatives of the clergy and merchants were also exempted from conscription duty. Anyone who wished (even serfs) could quite legally buy their way out of service, even if they were subject to it. Instead, they had to either purchase a very expensive recruiting card, issued in exchange for contributing a significant sum to the treasury, or find another recruit in their place, for example, promising a reward to anyone who wanted it.

"Rear Rats"

After lifelong service was abolished, the question arose of how to find a place in society for people who spent most of their adult life away from society, in a closed army system. In Peter’s times, such a question did not arise. If a soldier was still capable of at least some kind of work, they found a use for him somewhere in the rear; as a rule, he was sent to train new recruits; at worst, he became a watchman. He was still in the army and receiving a salary. In case of decrepitude or severe injuries, soldiers were sent to the care of monasteries, where they received a certain allowance from the state. At the beginning of the 18th century, Peter I issued a special decree, according to which all monasteries had to equip almshouses for soldiers.

During the time of Catherine II, the state took over the care of the needy, including old soldiers, instead of the church. All monastery almshouses were dissolved, in return the church paid certain amounts to the state, to which were added government funds, for which there was an Order of Public Charity, which was in charge of all social concerns. All soldiers who were injured in service received the right to a pension, regardless of the period of their services. Upon leaving the army, they were provided with a large one-time payment for building a house and a small pension. The reduction of service life to 25 years led to a sharp increase in the number of disabled people. In modern Russian, this word means a person with disabilities, but in those days any retired soldiers were called disabled, regardless of whether they had injuries or not. Under Pavel, special disabled companies were formed. With these words, the modern imagination pictures a bunch of unfortunate cripples and decrepit old people, but in fact only healthy people served in such companies. They were staffed either by veterans of combat service who are close to the end of their service life, but are healthy, or by those who, due to some illness, became unfit for combat service, or by those transferred from the active army for any disciplinary offenses. Such companies were on duty at city outposts, guarded prisons and other important facilities, and escorted convicts. Later, on the basis of some disabled companies, guards arose. A soldier who had served his entire service life could do whatever he wanted after leaving the army. He could choose any place of residence and engage in any type of activity. Even if he was called up as a serf, after his service he became a free man. As an incentive, retired soldiers were completely exempt from taxes. Almost all retired soldiers settled in cities. It was much easier for them to find work there. As a rule, they became watchmen, constables or “uncles” for boys from noble families. Soldiers rarely returned to the village. Over the course of a quarter of a century, people managed to forget him in his native land, and it was very difficult for him to once again adapt to peasant labor and the rhythm of life. Apart from this, there was practically nothing to do in the village. Starting from Catherine’s times, special homes for the disabled began to appear in provincial cities, where retired soldiers who were not capable of self-sufficiency could live on full board and receive care. The first such house, called Kamennoostrovsky, appeared in 1778 on the initiative of Tsarevich Pavel.

In general, Pavel was very fond of soldiers and the army, so after becoming emperor he ordered the Chesme Palace, one of the imperial travel palaces, to be converted into a home for the disabled. However, during Paul’s lifetime this was not possible due to problems with the water supply, and only two decades later he opened his doors to veterans of the Patriotic War of 1812. Retired soldiers became one of the first categories of people entitled to a state pension. Soldiers' widows and young children also received the right to it if the head of the family died during service.

"Soldiers" and their children

Soldiers were not forbidden to marry, including during service, with the permission of the commander. Soldiers' wives and their future children were included in a special category of soldiers' children and soldiers' wives. As a rule, most of the soldiers' wives got married even before their chosen ones entered the army.

"Soldiers" after their husband's conscription for service automatically became personally free, even if they had previously been serfs. At first, recruits were allowed to take their family with them to serve, but later this rule was abolished and the families of recruits were allowed to join them only after they had served for some time. All male children automatically fell into a special category of soldiers' children. In fact, from birth they were under the jurisdiction of the military department. They were the only category of children in the Russian Empire who were legally obliged to study. After studying in regimental schools, “soldiers’ children” (from the 19th century they began to be called cantonists) served in the military department. Thanks to the education they received, they did not very often become ordinary soldiers, as a rule, having non-commissioned officer positions or serving in non-combatant specialties. In the first years of its existence, the regular army usually lived in field camps in the summer, and in the cold season went to winter quarters - being stationed to stay in villages and villages. Huts for housing were provided to them by local residents as part of the housing obligation. This system led to frequent conflicts. Therefore, from the mid-18th century, special areas began to emerge in cities - soldiers' settlements. Each such settlement had an infirmary, a church and a bathhouse. The construction of such settlements was quite expensive, so not all regiments received separate settlements. In parallel with this system, the old billet, which was used during military campaigns, continued to function. The barracks we are accustomed to appeared at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries and at first only in large cities.

By call

Throughout the 19th century, the service life of recruits was repeatedly reduced: first to 20 years, then to 15 and finally to 10. Emperor Alexander II in the 70s carried out a large-scale military reform: conscription was replaced by universal conscription. However, the word “universal” "should not be misleading. It was universal in the USSR and is in modern Russia, but then not everyone served. With the transition to the new system, it turned out that there were several times more potential conscripts than the needs of the army required, so not every healthy young man served, but only the one who drew the lot.

It happened like this: the conscripts cast lots (pulled pieces of paper with numbers from a box). According to its results, some of the conscripts were sent to the active army, and those who did not draw lots were enlisted in the militia. This meant that they would not serve in the army, but could be mobilized in case of war. The conscription age was somewhat different from the modern one; they could not be drafted into the army before the age of 21 and after the age of 43. The conscription campaign took place once a year, after the end of field work - from October 1 to November 1. All classes were subject to conscription, with the exception of the clergy and Cossacks. The service life was 6 years, but later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was reduced to three years for infantry and artillery (in other branches of the military they served for four years, in the navy for five years). At the same time, those who were completely illiterate served a full term, those who graduated from a simple rural parochial or zemstvo school served for four years, and those who had a higher education served for a year and a half. In addition, there was a very extensive system of deferments, including based on property status. In general, the only son in the family, the grandson of grandparents who had no other able-bodied descendants, the brother who had younger brothers and sisters without parents (that is, the eldest in a family of orphans), as well as university teachers were not subject to conscription. property status was provided to business owners and migrant peasants for several years to organize their affairs, as well as to students of educational institutions. Part of the foreign (i.e., non-Christian) population of the Caucasus, Central Asia and Siberia, as well as the Russian population of Kamchatka and Sakhalin, were not subject to conscription. They tried to recruit regiments on a territorial basis, so that conscripts from the same region would serve together. It was believed that the joint service of fellow countrymen would strengthen cohesion and military brotherhood.

***

The army of Peter the Great became a difficult test for society. Unprecedented conditions of service, lifelong service, separation from their native land - all this was unusual and difficult for the recruits. However, in Peter’s times this was partly compensated for by excellent working social elevators. Some of Peter's first recruits laid the foundation for noble military dynasties. Subsequently, with the reduction of service life, the army became the main instrument for the liberation of peasants from serfdom. With the transition to the conscription system, the army turned into a real school of life. The length of service was no longer so long, and conscripts returned from the army as literate people.

To recruit the army necessary to fight the Great Northern War of 1700-1721, Peter I introduced conscription in 1699. Russia became the first country in the world to implement compulsory “conscription” into the army.

The first intake amounted to 32 thousand people. Recruitment was not of an individual, but of a communal nature, that is, the population of a particular territory was told the number of recruits that it should supply to the state. Men from 20 to 35 years old were involved in the recruitment service. For most of the 18th century, service was for life. Only in 1793 was service limited to 25 years.

During the reign of Peter I, a record number of recruitments were carried out - 53. In total, about 300 thousand people were called up for military service. Due to losses in battle and desertion, the total number hardly exceeded 200 thousand people. To this were added more than 100 thousand irregular troops: Cossacks, mounted Tatars and Bashkirs.

By 18th-century standards, Russia had a gigantic army. Under Peter I, the population was 12-13 million people, therefore, 2.5% of the population was put under arms. In European countries at that time, the share of military personnel from the country's population did not exceed 1%. Moreover, the size of the army did not decrease after the end of the Great Northern War, but continued to grow throughout the 18th century. The intensity of recruitment reached its climax during the Seven Years' War, when 200 thousand people (mostly peasants) were conscripted during the five years of Russian participation in this conflict. By this time the army had grown to 300 thousand people. By the end of the 18th century, the Russian Empire apparently had the largest regular army in the world - 450 thousand people.

I. Repin “Seeing off a recruit”, 1879.

The maintenance of such an army required enormous expenditures from the treasury. Under Peter I, warring Russia devoted an average of 80% of budget income to military expenditures, and in 1705 a record was set at 96%. In fact, the entire country worked only for the development of the army and military industry. In the second half of the 18th century, in years of peace with the most negative economic conditions, the Russian army continued to absorb 60-70% of the budget. By the beginning of the 19th century, due to rapid population growth, the share of military expenditures proportionally decreased, but remained at the same high level - 50-60%.