At the Nizhyn gymnasium. Nizhyn Gymnasium of Higher Sciences Nizhyn Gymnasium Gogol

The years of youth are the time of character formation, determination of life priorities, choice of one’s vocation and place in society. It is no coincidence that many writers devote entire books to this period of their lives, such as “Youth” by L.N. Tolstoy or “My Universities” by M. Gorky. Gogol does not have such a book, but this does not mean at all that this period of his life passed unnoticed and gave the writer little for his future life. In the article we will look at what Gogol's childhood was like. Let's talk about who he communicated with and what his interests were related to.

Gogol's childhood was spent in Ukraine - in the village of Vasilyevka, where there was a small estate of his father Vasily Afanasyevich Gogol-Yanovsky, from where little Nikolai had the opportunity to travel with his parents to Sorochintsy, and sometimes to Poltava, and nearby was Dikanka, which is so well known to all of us from Gogol’s famous book “Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka”. All these places were later mentioned in one way or another in the writer’s works, but the name of the city where he lived for seven years while studying at the gymnasium is unlikely to be immediately remembered by many admirers of Gogol’s work. And yet Nizhyn is a city with which much was connected in the life of the future writer.

Having received, like most of his contemporaries from noble families, his initial education at home, Nikolai was sent to the city of Nezhin, which was located not far from his native place, to continue his studies. The Gogol-Yanovsky family had highly educated people, despite the fact that they lived far from the capitals, and their environment was more reminiscent of the heroes of Gogol’s stories - “Old World Landowners”, “The Story of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich” and many others. In the Gogol-Yanovsky family, many were associated with the clergy. The writer's great-grandfather, Father John Gogol, graduated from the Kyiv Theological Academy. It was also completed by Gogol’s grandfather Afanasy Demyanovich.

Maybe that’s why there are so many clerks, priests, and priests in Gogol’s works. Of course, we all remember Khoma Brut, the seminarian from the story “Viy,” and the clerk of the Dikan Church, Foma Grigorievich (“The Evening on the Eve of Ivan Kupala,” “The Missing Letter,” “The Enchanted Place”) and many others. Gogol's father also graduated from the theological seminary in Poltava, but he remained a landowner, and after getting married, he devoted himself entirely to family affairs. Gogol's father and mother were deeply religious and pious people, as evidenced by the fact that next to the house in Vasilyevka there is a church built by his parents in gratitude to God for the birth of their son. The image of St. Nicholas was especially revered - Gogol’s mother Maria Ivanovna baptized him and named him Nicholas - as she promised even before the birth of the child in front of the image of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, to whom she prayed for the salvation of her son. The same deep faith was characteristic of the writer himself, and he always carried the icon of St. Nicholas with him on all his travels.

But in the Gogol house there was also a lot of secular literature. The writer's mother, Maria Ivanovna, was raised in the family of her wealthy aunt, Anna Matveevna Troshchinskaya. Here she received a very good education for those times: she knew literature well, knew how to play the piano, and dance. And her husband was fond of theater, although, of course, in Vasilyevka, which was remote from all centers of cultural life, there was no real big theater. But the Troshchinsky estate, which was located nearby, had its own theater, in which Vasily Afanasyevich not only acted as an actor, but also designed performances, and himself composed comedies, which were staged here. It was here that little Nikolai first developed an interest in theater and drama, which later developed during his years of study at the Nezhin gymnasium. So, what was this educational institution where Nikolai Gogol spent his childhood?

The Nizhyn Gymnasium of Higher Sciences was founded by Alexander I just a year before Nikolai Vasilyevich entered there in 1821. It became one of the new educational institutions that were then created in many Russian cities. Like the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, it was an educational institution where future educated officials, learned men, and military men were to be trained from the nobles. Sometimes Nizhyn gymnasium is also called a lyceum.

Many wonderful people came from here, such as the writer Grebenka, playwright Nestor Kukolnik. The bias in education was humanitarian, and in the first place was the study of history, literature, law and languages. The director of the gymnasium had the title of Master of Literary Sciences and Doctor of Philosophy, and as a surgeon he operated on the wounded in hospitals during the War of 1812.

Other professors at the gymnasium also had a European education and were seriously involved in science and literature. Thus, the young Latinist I.G. Kaluzhsky in 1827 published the book “Little Russian Village”, in which he processed the material of Ukrainian folklore. True, professor of literature Nikolsky, no stranger to literary pursuits, was guided by the tastes of the 18th century, creating his solemn odes and edifying poems.

Even outwardly, the gymnasium was completely different from what surrounded it. It rose in the midst of a provincial town like a temple of science. Here they read and translated Schiller and Goethe, wrote poetry, and copied “Eugene Onegin” at night. There was a good library at the gymnasium.

All this contrasted so much with the atmosphere that reigned in the town itself, which lived primarily by trade. The main event here was the fairs, which were held four times a year. The streets of the town were drowning in mud - only one, the central one, was paved. Pigs and cows roamed around Cathedral Square, and residents huddled in small one-story houses. The best buildings that were shown to visitors were the lyceum, a charitable institution and the district court. This is why Gogol showed such a picture in his “The Inspector General”, and then in “Dead Souls”. Already during his years of study in Nezhin, the observant young man stored in his memory those impressions that later helped him create a picture of life in the district and provincial towns of Russia. But the beginning of literary creativity is also connected with the Nizhyn gymnasium.

It was here that Gogol began to seriously study literature. The high school students formed their own literary circle, published a magazine, read each other their own works and discussed literary novelties. But not a single one of Gogol’s youthful works has survived. We can judge them only by the poem “Hanz Küchelgarten,” which he published in St. Petersburg and which had such an unfortunate fate in criticism.

What other interests did Gogol the high school student have? Like many of his contemporaries, he was fond of drawing, but he achieved great achievements in this. According to eyewitnesses, Gogol was an excellent actor. Moreover, he was especially good at comic roles. Thus, in Fonvizinov’s “The Minor,” Mitrofanushka was played by the Puppeteer, Sophia by A. Danilevsky (female roles in the gymnasium theater were also played by boys), and Mrs. Prostakova was played by Gogol.

As Nikolai Vasilyevich’s classmate and his closest friend throughout his life, A. Danilevsky, later said, if the future writer “had entered the stage, he would have been Shchepkin.” But the experience that he gained while studying at the gymnasium certainly was not in vain. There is one very interesting episode that shows Gogol’s comic talent and acting skills. In 1835, Nikolai Vasilyevich went to visit his relatives. His travel document stated that he was an adjunct professor (he was then teaching at St. Petersburg University). But the station guards read the incomprehensible word “adjunct” as “adjutant.” Who knows, maybe this is the adjutant of some important general, they thought. L Gogol did not try very hard to disappoint the guards of the postal stations. He was wearing a St. Petersburg dress, in the latest fashion, and he also showed some strange interest in various little things: he asked to show the stables, asked how many horses were at the station, and what they were fed with. Gogol's friend, who was traveling with him, also tried to play along. So the caretakers believed that some important person from St. Petersburg was coming, and the friends drove all the way to Poltava without any obstacles.

Literary fame was still ahead, and the years of study, which, as we saw, gave a lot to the future writer, were already coming to an end. I had to choose my future path. It would seem that a graduate of such an educational institution should first of all dream of a career as a government official. But Gogol’s choice fell on the literary field, although he did not openly tell anyone about it. He announced to his mother and friends that he was preparing himself for a legal career, but when leaving for St. Petersburg, he took with him his poem “Hans Küchelgarten” as his most valuable asset. This ended his years of study in Nezhin, and this ended Gogol’s childhood. Youth was ahead, a time of hopes and achievements, disappointments and new discoveries.

Vasily Afanasyevich [Gogol, father of N.V. Gogol. - Note], having learned about the opening in Nizhyn at the beginning of 1821 of a new educational institution - the Gymnasium of Higher Sciences, Prince. Bezborodko, “immediately began making inquiries. According to the information received, the Nizhyn gymnasium seemed to be a reputable and serious educational institution [in comparison with the Poltava povet school. - Note], in which, as stated, “all the sciences that are taught in universities will be taught,” and those who graduate will receive the same certificates and benefits as students.”

In the spring of 1821, eleven-year-old Gogol was taken to Nizhyn, and on May 1, after an entrance exam, he was admitted to the gymnasium

The Gymnasium of Higher Sciences of Prince Bezborodko in Nizhyn was established “for the special benefit of educating the children of poor and disadvantaged nobles of the Little Russian Territory and preparing them for public service.” The Nizhyn gymnasium was the only higher educational institution for most of the left bank of Ukraine, but it did not provide any specific specialty, preparing personnel for local officials from the nobility. Studying at the Gymnasium of Higher Sciences lasted nine years and was divided into three courses over three years - lower, middle and higher. The last, highest course was equivalent to a lyceum, or university, and had two departments - philosophical and legal.

In the system of gymnasium teaching, philosophical, legal and humanitarian disciplines occupied the main place. Professor of Russian literature P. Nikolsky, the author of the then widespread theory of literature, “rhetoric,” read the history of literature from a classicist position. He did not recognize Pushkin and was hostile to new phenomena in literature. “In general, our scientific and literary education was done, one might say, self-taught,” recalled one of the former students. - Literature professor Nikolsky had no idea about ancient and Western literatures. In Russian literature he admired Kheraskov and Sumarokov; Ozerov, Batyushkov and Zhukovsky were dissatisfied with the classics, and the language and thoughts of Pushkin were trivial, recognizing, however, some harmony in his poems... Naughty comrades in the 5th and 6th grades, obliged to pay weekly tribute to poems, used to rewrite them from magazines and almanacs, short poems by Pushkin, Yazykov, book. Vyazemsky was introduced to the professor as one of their own, knowing well that he was not involved in modern literature at all. The professor solemnly subjected these poems to strict criticism, expressing regret that the verse was smooth and of little use...”

The program for literature and rhetoric for the 6th grade for 1827 indicates a number of authors of the Middle Ages, antiquity and Russian of the 18th century

This program gives an idea of the range of knowledge that Gogol took from the gymnasium: “In the sixth grade, one should study aesthetics or analyze elegant rhetoricians, such as: Demosthenes, Cicero, Muret, Bossuet, Fletier, Massillon, Bourdalou, Feofan Prokopovich, Eminence Yavorsky, Gideon , Plato, Anastasius and others; analysis of writers such as: Jerusalem, Fenelon, Thomas, Carancioli, Bem, Tatishchev, Emin, Karamzin and others; and, finally, an analysis of elegant poets, such as: Homer, Horace, Virgil, Ovid, Petrarch, Camoens, Tass, Milton, Boileau, Racine, Pope, Lomonosov, Sumarokov, Kheraskov, Derzhavin, Zhukovsky and others; but without further speculation, speculation and speculation.” How characteristic is this instruction about the study of aesthetics and literature “without further speculation,” expressing the protective direction that government authorities tried to give to science. After all, ancient “rhetoricians” and church preachers occupied the main place in the study of aesthetics and eloquence. In the “analysis” of literary works, Russian literature is represented by a very limited circle of writers: it is characteristic that almost all satirical literature of the 18th century was excluded from the program - Fonvizin, Novikov, Krylov, not to mention Radishchev. New Western Literature was also not represented in school teaching. Gymnasium students themselves supplemented with reading the range of knowledge that they received from school teaching.

Gogol negatively assessed the gymnasium under its first director, Orlai.

But after Orlay left at the end of 1826, when the direction of gymnasium life was determined by a group of advanced professors led by inspector N. G. Belousov, Gogol’s attitude towards the gymnasium changed. It is this period that he calls the happiest period in the Nizhyn Gymnasium of Higher Sciences: “...we don’t have a director,” Gogol informs his mother in a letter dated November 16, 1826, “and it is desirable that we don’t have one at all. Our boarding house is now at the best level of education... which Orlai could never achieve; and the reason for all this is our current inspector; we owe our happiness to him; the table, the attire, the interior decoration of the rooms, the routine, now you won’t find all this anywhere except in our establishment. Advise everyone to bring their children here: in all of Russia they will not find anything better.”

The Nizhyn gymnasium did not receive the significance in Gogol’s life that the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum had for Pushkin, nevertheless its role in the formation of the views of the young Gogol was very significant. Along with the shadow sides, routinism and scholasticism of school teaching, new, advanced trends penetrated into the gymnasium, which had a beneficial effect on the development of the future writer. And in the Nizhyn Gymnasium of Higher Sciences there were people who stood at the level of the progressive views of their time. From the end of 1826, the duties of the director were performed by the professor of mathematics and natural sciences Shapolinsky for more than two years. According to one of the students of the lyceum, P. Redkin, a circle was grouped around Shapolinsky and Belousov, to which belonged “noble, intelligent and knowledgeable people” - Landrazhin, Singer, Soloviev, who enjoyed “love and popularity among students.” In the opposite camp were reactionary professors led by Bilevich.

The students of the gymnasium were also divided into two camps: a privileged group of wealthy nobles and children of less wealthy parents.

The rich “aristocrats” among the schoolchildren did not favor Gogol. The school nickname - “mysterious Karla”, according to A. Danilevsky, was given to Gogol because he kept himself apart from the aristocratic group of schoolchildren. Not only the awareness of his unequal position among privileged students, but also constant inner depth, the desire for a previously set lofty goal separated the young man from his gymnasium comrades. In a letter to his uncle Pyotr Kosyarovsky dated October 3, 1827, Gogol admits: “Distrustful of anyone, secretive, I did not trust my secret thoughts to anyone, I did not do anything that could reveal the depths of my soul.” The young man had a hard time with the death of his father, who died in April 1825, having lost in him his “most faithful friend,” his “all precious” “heart” (letter to his mother dated April 23, 1825). With the death of his father, the family's financial difficulties increased even more, and Gogol, throughout his entire stay at the gymnasium, constantly felt the need for money, even for the most insignificant and necessary expenses.

[Stepanov N. L. Gogol. - M.: Young Guard, 1961. - 432 p. - (Life of wonderful people).]

Nizhyn Gymnasium

Now, after the death of his younger brother, even greater hopes were placed on Nikolai. He had to get an excellent education at all costs! A classical gymnasium, founded by Prince Bezborodko, opened in Nizhyn just at this time. With the help of Troshchinsky, Nikolai Gogol was identified in Nizhyn as one of the pupils under state care, which freed parents from paying tuition and boarding fees. In the spring of 1821, his father brought Nikolai to the gymnasium, where the boy immediately did not like it. But the holidays were just around the corner, so it was possible to be patient. His future comrade V.I. Lyubich-Romanovich described his arrival as follows: “He was not only wrapped in various scrolls, fur coats and blankets, but simply sealed. When they began to expose him, they could not get to the bottom of the frail, extremely ugly boy disfigured by scrofula for a long time.” Yes, it is only in literature textbooks that geniuses are born immediately in the form of bronze monuments! And in life they sometimes even get scrofula and are ugly, scared and unsociable.

Gogol didn’t really want to study. For example, before a math test, we’ll go up to mom and say that somehow my throat hurts and that everything’s not right. And why should things have been different in the 19th century? So the future classic tried to evade school: “When I arrived in Nizhyn, the next day my chest began to hurt. At night my chest hurt so much that I could not breathe freely. In the morning it felt better, but my chest still hurt, and therefore I was afraid that something bad would happen, and besides, I was very sad being apart from you.” But his parents showed firmness, because they could not give him a good education at home, and in the same year another girl was born in the family - Anna.

But the daily routine at the Nizhyn gymnasium was such that it was really time to run away. We got up at half past five in the morning. We washed ourselves and went to church in formation to serve a prayer service before classes. Then hurry to the dining room to drink tea and go to classes - from nine to five o'clock in the evening. There was lunch, of course. Dinner at eight, and at nine, after evening prayer, please turn off the lights and bye-bye. In the warm season, you could still spend time in the park, but where can you go in winter? And when should I teach my lessons? And there were a lot of subjects: the Law of God, literature, Russian, Latin (for which Gogol had zeros and ones - he read books under his desk!), Greek, German, French, physics, mathematics, political disciplines, geography, history, military art, drawing, dancing.

Gogol the Gymnasium Student (portrait of an unknown artist from the 1820s)

Nikolai Gogol was also not noticed in exemplary behavior, just read the cool magazine: “December 13 (such and such Yanovsky stood in the corner for bad words; December 19, Prokopovich and Yanovsky for laziness without lunch and in the corner until they learned their lessons. On the same date, Yanovsky for stubbornness and laziness especially - without tea. December 20 (such and such) and Yanovsky - for bread and water during lunch. On the same date, N. Yanovsky, for the fact that he studied during priest class with toys, was without tea.”

At first, his comrades did not like him and even called him “the mysterious dwarf.” He was unsociable, but amazingly observant and sharp-tongued, amazingly imitating other people’s manners and features, so that he could drive anyone, teachers and classmates alike: “You know, Ritter, I’ve been watching you for a long time and noticed that you don’t have human , and bull's eyes." And so every day. The question is, who will like this?

When Nikolai Gogol was sixteen years old, a terrible tragedy occurred in the family. His father, who had been ill for a long time, left for treatment, but never returned home. The mother was pregnant at that time, her despair knew no bounds. So the school bully and unsociable remained the only man in the family, and also the eldest of the children. After his father's death, his younger sister Olga was born. And there were also the elders Maria, Anna and Elizabeth, mother and grandmother! He grieved for his father, supported his mother, now felt responsible for everything and, probably, was a little proud. Now in his letters Nikolai Gogol tried to delve into all the details of farming. However, where to go, I still had to ask for pocket money.

Over time, real friends began to appear in the gymnasium, and all of them eventually became, if not famous, then quite famous people - Alexander Danilevsky, Nestor Kukolnik (later the author of patriotic tragedies), Evgeniy Grebenka (a poet who wrote in Ukrainian), Konstantin Basili ( diplomat and author of books about Turkey and Greece), Nikolai Prokopovich (teacher and poet), Vasily Lyubich-Romanovsky (poet, historian and translator). It is no coincidence that all of them, as adults, took up literature. Firstly, in the gymnasium they established something like a library, where Nikolai Gogol was the librarian. He meticulously made sure that the books were not smeared or damaged, forcing him to wear special finger pads when reading! And this is not surprising, because these books were bought by friends themselves with their own meager funds. Well, what kind of money does a high school student have? Literature lessons were terrible, and Gogol took pleasure in imitating P. I. Nikolsky, who taught this subject, for whom worthwhile literature ended, as usual, a hundred years ago. He didn’t even want to hear about Pushkin and Batyushkov. Therefore, “Gypsy”, “Eugene Onegin” and “Poltava” were copied by hand into a notebook. The friends themselves also wrote poems and read them to each other. Once Gogol tried his hand at prose. This is the ball "The Tverdovich Brothers, a Slavic Tale." But his friends tore this attempt to smithereens and came to the conclusion that this was clearly not his path. Poetry is a completely different matter! Do you understand now why he started with “Hans Kuchelgarten”? So the first prose opus was sent to the stove without regret.

The company also published handwritten magazines “Star”, “Dawn of the North”, “Meteor of Literature” and even “Dung of Parnassus”. Nikolai Gogol could do everything in such magazines from poetry and prose to illustrations. One of these magazines was even material evidence at the height of the scandal with the dismissal of one of the liberal teachers from the gymnasium, which had already become a lyceum. This, they say, is what freethinking can lead to!

And then everyone became interested in the theater, and they themselves asked the director of the lyceum to organize it. Parents helped with costumes and other necessary theatrical things. Gogol played so well that his friends were sure that he would go on stage. He played Prostakova in “The Minor” in such a way that those who saw him in this role assured that even the actors of the imperial theaters were very far from him.

However, the schoolchildren were growing up, and the time was approaching when it was time to leave Nizhyn. Gogol did not see a point of application for himself in his native places; St. Petersburg beckoned him. Some of his good friends had already tried their hand at the distant northern capital; things may not have worked out brilliantly for them, but it was still St. Petersburg. Its brilliance at such a distance seemed particularly irresistible, and its difficulties insignificant. The career of an official seemed to Gogol to be a sublime service to the fatherland: “I will test my strength to carry out important, noble work: for the benefit of the fatherland, for the happiness of citizens, for the good of the lives of others, and hitherto indecisive, not confident (and rightly so) in myself, I flare up with the fire of proud self-awareness , and my soul seems to see this unearthly angel, firmly and adamantly pointing everything towards the direction of the greedy search... In a year I will enter public service.”

Well, we will go to St. Petersburg for our hero!

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 1

✪ MIU graduation 2010

Subtitles

Gymnasium of Higher Sciences (1820-1832)

The first steps to found the gymnasium were taken by Count I. A. Bezborodko. In 1805, the highest permission from Emperor Alexander I for its discovery was received. The gymnasium was named Gymnasium of Higher Sciences of Prince Bezborodko, because the main funds intended for its maintenance came from a capital of 210,000 rubles, bequeathed by the Chancellor of the Russian Empire, Prince A. A. Bezborodko. In addition to them, I. A. Bezborodko donated a “place with a garden”, which was supposed to house the gymnasium building, and additional funds (15,000 rubles annually). However, the opening of the gymnasium never took place.

The gymnasium was opened fifteen years later, after the death of Count I. A. Bezborodko, with funds donated by him for this purpose, by his grandson, Count A. G. Kushelev-Bezborodko. The highest rescript on the founding of the gymnasium was signed by Emperor Alexander I on April 19 (May 1). The charter of the gymnasium was approved only on June 27, 1824, and the charter of establishment was approved on February 19, 1825; however, classes began on September 4, 1820 (according to other sources - on August 4).

The purpose of the gymnasium was to give Little Russian nobles “convenience in raising their children in pious rules, to acquire knowledge in languages and general sciences.” The period of study in the gymnasium was set at 9 years and was divided into categories of three classes in each. Graduates of the gymnasium, depending on their academic success, had the right to the rank of XII (for “candidates”) or XIV (for “actual students”) classes according to the “Table of Ranks”. The certificates issued by the gymnasium had “equal validity” with the university certificates and exempted “those who received them from testing for promotion to the highest ranks.”

The structure of the gymnasium was very similar to the Demidov School created a little earlier in Yaroslavl.

The subjects of teaching were: the law of God, ancient languages, Russian, German and French, mathematics, history and geography, Russian literature and ancient languages, philosophy, natural and folk law, technology with chemistry, natural history, government, financial science, Roman law with its history, Russian civil and criminal law and legal proceedings.

The composition of the students was determined as follows:

- 24 pupils at the expense of Bezborodko;

- 3 - children of military officials;

- free boarders of no more than 150 students;

- coming listeners.

The gymnasium was donated by: the government - 28 books; honorary trustee - 2,610 volumes and 20 thousand rubles. for a physical office and initial setup.

The first director of the gymnasium was V. G. Kukolnik (1820-1821)

Teachers - 2; students: in the boarding school - 17 (all are nobles).

The gymnasium was donated by: private individuals - 513 books.

Teachers - 9; students: in the boarding house - 44 and visiting - 13 (all are nobles).

The gymnasium was donated by: the government - 46 books; by private individuals - a large silver medal for the conclusion of peace between Russia and the Ottoman Porte in 1791, as well as 90 books.

Teachers - 9; students in the boarding school: from nobles - 56, from Greeks - 6 and incoming students: from nobles - 49, from commoners - 4, merchants - 1, burghers - 6.

The gymnasium was donated by: the government - 19 books; honorary trustee - 34 books, 5 geographical maps, 8 chronological historical tables, 78 originals for drawing, a silver medal for the opening of trade in the Baltic Sea and various castings of Greek ancient vessels, a mineralogical cabinet of 642 mineral specimens; by different persons - 154 books.

Teachers - 23; students in the boarding school: from nobles - 71, from Greeks - 6 and incoming students: from nobles - 57, commoners - 4, merchants - 3, burghers - 7, Greeks - 7, Cossacks - 1. Total students - 156.

The gymnasium was donated by: the government - 17 books; private individuals - 55 books and 13 geographical maps.

Teachers - 16; students in the boarding school: from nobles - 71, from Greeks - 6 and incoming students: from nobles - 98, commoners - 6, merchants - 4, burghers - 7, Greeks - 9, Cossacks - 1. Total students - 202.

The number of students grew mainly due to free students. The first issue took place in 1826. In 1827, 3 were graduated as candidates. In 1828, 5 were graduated as candidates, 5 as full students.

Among the outstanding teachers of the gymnasium were Professor of Legal Sciences N. G. Belousov (from May 1825), Professor of Mathematical Sciences K. V. Shapalinsky, Professor of French Literature I. Ya. Landrazhin, Professor of German Literature Fyodor Iosifovich (Friedrich-Joseph) Singer, Jr. professor of natural sciences N.F. Soloviev and others (the first four were dismissed in November 1830 after the investigation of the “Case of Freethinking”). The Latin language was taught in 1825-1829 by I. G. Kulzhinsky.

At the end of the 1820s, unrest arose in the gymnasium and a trial began regarding the freethinking of some professors, which was the reason for its transformation in 1832 into a physics and mathematics lyceum.

Nizhyn Physics and Mathematics Lyceum (1832-1840)

According to the new charter, approved on October 7 (19), the gymnasium was renamed into a physics and mathematics lyceum. At the same time, the gymnasium classes were gradually (by 1837) closed and only the three higher classes were left.

The staff of the Lyceum consisted of 6 professors who taught mathematics and applied mathematics, physics, chemistry and technology, Russian literature, natural history, Russian history with statistics, two lecturers on French and German literature and a law teacher who taught the Law of God. The professor of pure mathematics in 1835-1836 was Karl Kupfer; chemistry was taught in 1833-1841 by court councilor I. Ya. Skalsky.

In total, there were five graduations from the physics and mathematics lyceum, with the number of those graduating with the right to the rank of XIV class being 147 people. By the end of the 1830s, the popularity of the lyceum had fallen sharply and there were no more people willing to enroll in the first year.

Teachers: N. H. Bunge (1845-1850; laws of government administration), P. N. Danevsky (1843-1853; civil laws),

The artistic world of Gogol Mashinsky Semyon Iosifovich

Chapter one “Gymnasium of Higher Sciences”

Chapter first

"Gymnasium of Higher Sciences"

There is no need to talk here about certain circumstances of Gogol’s childhood. All this, as well as many other facts of his biography, was often described in detail in various books. We will allow ourselves to make only one exception - in relation to the few years that the future writer spent at the Nizhyn gymnasium. They left a deep mark on Gogol's spiritual life. The first outbreaks of his creativity date back to the Nizhyn era; here his civic consciousness awakened; it was by this time that those traits in Gogol’s character began to form, which would later affect his personality, and partly in his artistic world. The archival materials I discovered at one time, only partially used in this book, allowed me to comprehend and understand a lot in a new way.

In 1820, a new educational institution opened in Nizhyn - the so-called “Gymnasium of Higher Sciences of Prince Bezborodko.” It belonged to the number of privileged educational institutions. Its task was to “train youth for the service of the state.” According to the charter, it, along with the Demidov School of Higher Sciences in Yaroslavl and the Richelieu Lyceum in Odessa, occupied “a middle place between universities and lower schools” and was almost equal to the first, differing from the second both in “the highest degree of sciences taught in it” and special “ rights and benefits."

The Nizhyn gymnasium was created as a closed educational institution. Strict discipline was established here, the observance of which was vigilantly monitored by teachers and guards. The unusually complicated system of governing the gymnasium also pursued the same goals. General management was carried out by the director, inspector and supervisors, in the educational area - by the board. The management of the gymnasium, in turn, was under triple control: the trustee of the Kharkov educational district, the honorary trustee Count A.G. Kushelev-Bezborodko - the grandson of the founder of the gymnasium - and, finally, the Ministry of Education.

This entire complex administrative structure, as well as the educational system, was aimed at instilling in students loyalty to “the Tsar and the Fatherland” and qualities that would correspond to the formula: “Don’t think, don’t reason, but obey.”

Although the Nizhyn gymnasium was by no means considered an ordinary educational institution, the organization of education here was not entirely satisfactory. This was explained primarily by the selection of professors and teachers, a significant part of whom were poorly suited to their purpose.

The history of Russian literature was taught at the gymnasium by Parfeny Ivanovich Nikolsky, a dry and arrogant pedant who taught his course in strict accordance with the Old Testament instructions on rhetoric and literature.

Among the routine teachers of the Nezhin gymnasium, another gloomy figure should be noted - Ivan Grigorievich Kulzhinsky. Coming from the clergy, Kulzhinsky graduated from the Chernigov Seminary and taught Latin in Nizhyn for four years (1825–1829). He also worked in the literary field, writing sentimental novels, stories and unbearably drawn-out dramas, collaborated in metropolitan magazines and was later a member of the Society of Russian Literature. As a teacher and writer, Kulzhinsky was extremely unpopular among the students of the gymnasium. When his essay “The Little Russian Village” was published in 1827, it immediately became the subject of ridicule from high school students, including Gogol. In a letter to his friend, G.I. Vysotsky, Gogol colorfully described how high school students make fun of the “literary freak” Kulzhinsky.

The relationship between Kulzhinsky and Gogol was hostile. And this can be clearly felt from the tone of the memoirs written by Kulzhinsky in 1854.

At the head of this group of routine teachers was the senior professor of political sciences, Mikhail Vasilyevich Bilevich, who arrived at the Nezhin gymnasium in December 1821. Prior to this, he served for fifteen years as a teacher of natural sciences and German at the Novgorod-Severskaya gymnasium, in which he, in addition, at various times taught commerce, technology and “experimental physics.” At first, Bilevich was assigned to the Nezhin gymnasium for the vacancy of professor of German literature, and two years later he was appointed professor of political science.

From the very beginning of his service at the gymnasium, Bilevich established himself as an outspoken reactionary, an ignorant and untalented person. The students at the gymnasium were afraid of Bilevich and hated him. Gogol also could not stand him, calling Bilevich and his like-minded people “school professors” (X, 85).

In May 1825, Nikolai Grigoryevich Belousov was assigned to the gymnasium as a junior professor of political sciences, and a year later he was also appointed to the position of boarding school inspector.

The twenty-six-year-old professor immediately fell in love with the students of the gymnasium; he was able to quickly establish good, friendly relations with them. Unlike many old teachers, Belousov was a man of progressive convictions, distinguished by a sharp mind and deep and versatile knowledge. In addition, he had enormous personal charm. “Fairness, honesty, accessibility, good advice, in decent cases, the necessary encouragement,” Nestor Kukolnik later recalled about him, “all this had a beneficial effect on the circle of students...”

Belousov was assigned to teach a course in natural law. In his lectures, he developed progressive ideas, captivatingly talked about the natural right of the human person to freedom, the great benefits of education for the people, and aroused sharp critical thought in the minds of his students. Professor Belousov's lectures found a lively response among high school students, and he soon became their favorite teacher. The same Nestor Kukolnik testified: “With extraordinary skill, Nikolai Grigorievich outlined to us the entire history of philosophy, and at the same time of natural law, in several lectures, so that in the head of each of us a firmly harmonious, systematic skeleton of the science of sciences was established, which each of us could already put into action according to his desire, abilities and scientific means.” And in the unpublished part of this memoir of his, Kukolnik spoke about Belousov even more expressively: “He was one of the most learned people in Russia. He was destined to shine brightly in the scientific and educational fields; It was not fate, but people who had no idea about this.”

Among the free-thinking part of the gymnasium teachers should also be named Kazimir Varfolomeevich Shapalinsky - senior professor of mathematical sciences, Ivan Yakovlevich Landrazhin - professor of French language and literature, Fyodor Iosifovich (Friedrich-Joseph) Singer - junior professor of German literature, as well as juniors who were close to this group professor of Latin literature Semyon Matveevich Andrushchenko and professor of natural sciences Nikita Fedorovich Solovyov.

Almost all of these people were invited to work in Nizhyn by Ivan Semenovich Orlay, who held the post of director of the gymnasium in 1821–1826. He was a man of broad culture: Doctor of Medicine, Master of Literary Sciences and Philosophy, author of numerous works on various fields of science. Contemporaries noted the progressive nature of his views and the courage with which he defended them. Orlai aroused great sympathy among the students of the gymnasium. Gogol mentions him with respect in his letters. In the materials of the investigation into the “freethinking case,” his name is often mentioned among the main culprits of the “unrest” in the gymnasium, although by that time Orlai no longer worked in Nizhyn. As Professor Moiseev wrote in one of his reports, the friendship of Orlay and Shapalinsky “was based on connections of a “secret society.” The head of the sixth department of the fifth district of the corps of gendarmes, Major Matushevich, reporting to Benkendorf in January 1830 about “unrest” in the Nizhyn gymnasium, called Orlai a man prone to secret societies and having “relations with people convicted of evil intentions against the government.”

The death of Orlai prevented Nicholas I from dealing with him in the same way as was done with a whole group of gymnasium teachers.

Gogol was enrolled in the Nizhyn “gymnasium of higher sciences” in May 1821. Timid and shy, he had difficulty getting used to the new living conditions in Nizhyn.

A significant part of the memoirs of contemporaries about the future writer’s stay at the Nizhyn gymnasium portrays Gogol either as a carefree, merry fellow, mischievous, eccentric, or as a secretive and self-absorbed teenager, living separately from the interests of most of his schoolmates, with little interest in the sciences taught. In addition, with the light hand of some memoirists, it became customary to portray Gogol the high school student as almost mediocre. Here is a characteristic statement from this point of view by V.I. Lyubich-Romanovich: “... at the time when we knew Gogol at school, we not only could not suspect him to be “great,” but we did not even see him as small.” I. G. Kulzhinsky, dissatisfied with Gogol’s success in his subject - the Latin language, later recalled: “This was a talent that was not recognized by the school and, to tell the truth, did not want or was not able to admit to the school.” Warden Perion expressed the same thought with rude straightforwardness: “It would be too funny to think that Gogol will be Gogol.”

Over the course of a century, such evidence was tirelessly quoted by the authors of popular biographies of Gogol, moving from book to book, and became not only familiar, but also acquired a reputation as reliable facts.

But just a few years after leaving Nezhin, almost all of Russia already knew Gogol.

It is known that Gogol’s versatile artistic talent was already evident in Nezhin. He could draw and had a penchant for painting. He was the organizer and soul of the amateur theater at the gymnasium. In Nizhyn, Gogol also developed an interest in literature.

The oppressive atmosphere of official scholasticism that reigned in the classes of some teachers forced the students of the gymnasium to seek satisfaction of their spiritual interests outside the classroom. The high school students were fond of the works of Pushkin, Griboedov, and Ryleev; they followed the latest literature, subscribed to the magazines “Moscow Telegraph”, “Moskovsky Vestnik”, and Delvig’s almanac “Northern Flowers”.

Interest in literature reigned among the students of the gymnasium, despite Nikolsky. Some of them even tried to compose themselves. Here, besides Gogol, N.V. Kukolnik, E.P. Grebenka, V.I. Lyubich-Romanovich, N.Ya. Prokopovich, who later became professional writers, and many others tried their pen, and many others, for whose biographies, however, “ “writing” turned out to be a passing episode. “At that time, literature flourished in our gymnasium,” recalled Gogol’s anonymous classmate, “and the talents of my comrades were already emerging: Gogol, Kukolnik, Nikolai Prokopovich, Danilevsky, Rodzianko and others who remained unknown due to the circumstances of their lives or went to an early grave. Even now, in my old age, this era of my life brings back touching memories to me. We led a cheerful and active life, we worked diligently...”

This contemporary testimony is reliable and significant. It is confirmed by many materials at our disposal and suggests that the atmosphere of the spiritual life of the students of the Nizhyn gymnasium was quite intense and interesting.

Gogol's interest in literature arose early. His first favorite poet was Pushkin. Gogol followed his new works, diligently copying the poems “Gypsies”, “Robber Brothers”, chapters of “Eugene Onegin” into his school notebook. A. S. Danilevsky says in his memoirs: “The three of us gathered (with Gogol and Prokopovich. - CM.) and read Pushkin’s Onegin, which was then published in chapters. Gogol already admired Pushkin then. It was still contraband at that time: for our literature professor Nikolsky, even Derzhavin was a new person.” Gogol's letters addressed to his relatives are always full of requests to send him the books and magazines he needs. He strove to keep abreast of everything that was happening in modern literature.

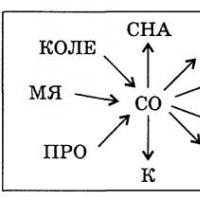

Already in the gymnasium, Gogol discovered a passion for literary creativity. T. G. Pashchenko testifies that this passion arose “very early and almost from the first days of his admission to the gymnasium of higher sciences.” Gogol tried himself in a variety of genres - poetry, prose, drama. Going home for the summer holidays in June 1827, he wrote to his mother: “Send a suitable carriage for me, because I am going with all the wealth of material and mental property, and you will see my works"(X, 96). Information about Gogol’s Nezhin “works” is very scarce. We know that he composed a number of lyrical poems, the ballad “Two Fishes”, the poem “Russia under the Yoke of the Tatars”, the satire “Something about Nezhin, or the law is not written for fools”, the tragedy “Robbers”, written in iambic pentameter, the story “Brothers” Tverdislavich." These initial experiments of Gogol have not survived.

For a number of years, there was a literary society in the gymnasium, at whose meetings the works of school authors were discussed, handwritten almanacs and magazines were published, which, unfortunately, also have not reached us.

Once, at a society meeting, Gogol’s story “The Tverdislavich Brothers” was discussed. The high school students gave a sharply negative review of this work and advised the author to destroy it. Gogol calmly listened to the comments of his comrades and agreed with them, immediately tore the manuscript into small pieces and threw them into the heated oven. Probably a similar fate befell his other works.

Gogol's school friends had a low opinion of his literary abilities, especially in the field of prose. “Practice in poetry,” one of his school friends, the Greek K. M. Basili, advised him, “but don’t write in prose: it turns out very stupid for you.” You’re not going to be a fiction writer, that’s obvious now.” And Gogol himself at that time gravitated more towards poetry than prose, although he did not at all attach any importance to his literary pursuits. Even the general direction of his creative interests was difficult to guess even then. “My first experiments, my first exercises in compositions, for which I acquired the skill during my recent stay at school,” he later recalled in his “Author's Confession,” “were almost all of a lyrical and serious nature. Neither I myself nor my companions, who also practiced writing with me, thought that I would have to be a comic and satirical writer” (VIII, 438). Although it was precisely in Gogol’s gymnasium years, by his own admission, also confirmed by many of his “classmates,” that some satirical inclinations definitely began to appear - for example, in the ability to surprisingly subtly imitate the funny character trait of an unloved professor or cut off some arrogant high school student with a well-aimed word . Gogol called this the ability to “guess a person.” Grigory Stepanovich Shaposhnikov, one of Gogol’s school friends, talks about him in his memoirs: “His cheerful and funny stories, his jokes and the very things, always smart and sharp, without which he could not live, were so comical that even now I can’t remember them without laughter and pleasure.”

Gogol’s satirical observation and his natural wit sometimes even manifested themselves in his work: for example, in the above-mentioned satire “Something about Nezhin, or the law is not written for fools”, in the acrostic “Behold the way of life of the wicked” on the high school student Fyodor Borozdin, nicknamed Rasstriga Spiridon. Of Gogol's Nezhin works, in addition to a few trifles and excerpts, only one poem has survived - "Housewarming". The poem by seventeen-year-old Gogol is marked with the stamp of famous poetic culture. It is written in the form of a lyrical reflection, very close in its intonation to the traditions of romantic elegy.

Gogol's lyrical hero is imbued with a mournful view of reality; he lost faith in its goodness and harmony and

I fell out of love with the joy of life

And he invited sadness to a housewarming party.

But sadness is not the external pose of our hero. She is an expression of his mental disorder and melancholy. In the past he was cheerful and bright, but then something happened on his way, and he began to fade:

Now, like autumn, youth withers.

I'm gloomy, I'm not having fun.

And I yearn in silence

And wild, and joy is not my joy.

V.I. Shenrok suggested that the minor tone of Gogol’s poem has an autobiographical basis and is caused by the sad circumstances associated with the death of his father. This was probably partly due to the influence of the romantic tradition on the young Gogol.

It must be said that Gogol’s spiritual development progressed very quickly during these years. He closely followed modern literature, greedily absorbed new ideas and sentiments that were forming in the consciousness of the advanced strata of Russian society. The echoes of the formidable political events that took place shortly before in the north and south of Russia reached Nezhin, although in a greatly weakened form, but provided the gymnasium youth with enough material for thinking about the most diverse phenomena of modern life and art. How serious and thorough these reflections were can be judged, for example, from one of Gogol’s school works that has come down to us, entitled “On What is Required from Criticism.”

According to the probable assumption of N. Tikhonravov, Gogol wrote it in the first half of 1828, that is, shortly before graduating from high school. The text of the essay takes up less than one printed page. It is written concisely, concisely and bears traces of the young Gogol’s serious thoughts on his chosen topic. Of the three surviving school works by Gogol - on Russian law, history and theory of literature - the first two are too descriptive and empirical in nature and almost devoid of elements of independent analysis. The latter, devoted to criticism, provides well-known material for judgments about the level of Gogol’s spiritual development.

“What is required from criticism?” - this is how the essay begins. The author emphasizes that he considers the solution to this issue “too necessary in our times” and formulates several conditions necessary for the successful development of criticism. It should be “impartial,” “strict,” “decent,” and, in addition, it must serve as an expression of “true enlightenment.” A critic must have the ability to correctly understand the idea of a work. And, what is especially important, a critic, when evaluating any work, cannot limit himself only to the sphere of art; he must be guided by “a true desire for good and benefit” (IX, 13).

Timidly and uncertainly, Gogol here gropes for the path to understanding the relationship between art and reality. And although Nikolsky gave this essay a rating of “fairly”, which in those days meant the highest score, the main ideas of the essay could not in any way be perceived by Gogol from the lectures of the routinist professor and were not even clearly consistent with his concepts about this subject.

In the senior classes of the gymnasium, literary life was in full swing. The works of the capital's authors and their own compositions were hotly discussed, and handwritten magazines and almanacs were published. Moreover, as it turns out now, there were much more of them than Gogol’s researchers and biographers previously assumed. A lot of handwritten works prohibited by censorship passed through the hands of high school students. All this could not go unnoticed by the reactionary part of the gymnasium teachers. And soon thunder struck.

In the fall of 1826, warden Zeldner reported to Belousov, who had taken office as inspector of the gymnasium, that he had found among the students a large number of books and manuscripts that were “inappropriate for the purpose of moral education.” Since wide publicity of this episode was inevitable, Belousov ordered the papers and books to be taken away from the students and reported the incident on November 27, 1826 to the acting director Shapalinsky.

Bilevich and Nikolsky repeatedly demanded that Belousov present the specified materials to the conference. Under all sorts of pretexts, Belousov avoided fulfilling this requirement, causing reproaches for patronizing the immoral behavior of his students.

Even in the midst of the “freethinking case,” when a dangerous political accusation hung over Belousov, he refused to hand over the materials taken from the gymnasium students, neglecting the resolutions of the conference and the orders of the new director of the gymnasium, Yasnovsky, who took office in October 1827. To Yasnovsky’s offer to show him the works taken from the students, Belousov replied that he “has reasons to keep them.” One day, in this regard, an incident broke out at a conference. Furious, Yasnovsky began shouting at Belousov and demanded that his student essays be returned immediately. The professor stated that he had no books or writings... not preserved!

Belousov continued his tactics even after the arrival of the authorized Minister of Education, Aderkas, who repeatedly reminded him of the need to present the papers and books taken from the students. Belousov kept the secret for three and a half years. And finally, he had to reveal it when, on April 11, 1830, the enraged Aderkas ordered him to immediately submit the materials in an ultimatum.

In Aderkas’ files there is a “Register of Books and Manuscripts” written in Belousov’s hand. This document is of outstanding interest. It consists of four sections:

« A. Magazines and almanacs, which were compiled by students of the gymnasium before I took office as inspector».

Here we learn for the first time the names of a number of handwritten publications published in gymnasiums, in which Gogol undoubtedly took part. In addition to the well-known almanacs “Meteor of Literature”, which in Aderkas’s materials is called “godly and godless”, “Parnassian Dung”, this list includes: the magazines “Northern Dawn” (1826, No. 1, January - consists of 28 sheets, No. 2, February - from 49 sheets and No. 3, March - from 61 sheets), “Literary Echo” (1826, No. 1–7, 9-13), almanac “Literary Interval, compiled in one day + 1/2 by Nikolai Prokopovich 1826 "and some nameless publication, "literary something" (1826, No. 2), as Belousov calls it. All listed manuscript publications are dated one year. According to Belousov, in the same year, 1826, students “composed and compiled various magazines and almanacs, of which there were more than ten at that time.”

I. A. Srebnitsky, examining the Nizhyn archive at the beginning of this century, noted with disappointment that it contained “absolutely no mention of the journal activities of Nizhyn high school students and Gogol among them.” The Aderkas materials we discovered significantly expand ideas on this matter.

P. A. Kulish in his “Notes on the Life of N. V. Gogol,” referring to the story of one of Nezhin’s students, mentions the magazine “Zvezda,” published in the gymnasium. In 1884, an article by S. Ponomarev was published in “Kyiv Antiquity” describing one issue of the journal “Meteor of Literature”, which accidentally came into his possession. The author of the article suggested: is this the same magazine that Kulish mentions? “In its title,” wrote S. Ponomarev, “the biographer could easily say: “Meteor”, “Star” are somewhat close to each other and could get mixed up in memory.”

The “Register” of Belousov that we found allows us to bring greater clarity to this issue. S. Ponomarev's assumption turns out to be incorrect. “Zvezda” has nothing to do with “Meteor of Literature”; it is another handwritten publication - apparently the one called “Northern Dawn” in the “Register”.

The name of the magazine, naturally, suggests that the students of the “gymnasium of higher sciences” were familiar with the almanac of Ryleev and Bestuzhev “The Polar Star”. It was probably in memory of this publication that the Nezhin residents decided to name their handwritten journal “Northern Dawn”. To more accurately reproduce the title of the Decembrists' almanac was, of course, risky. It is no coincidence that in the “oral traditions” of the Nezhin people, to which Gogol’s first biographer P. A. Kulish refers, the handwritten journal appears under the name “Star”. It is extremely interesting that the initiator of this publication was Gogol. Referring to the same “oral traditions,” Kulish notes that Gogol filled almost all sections of the magazine with his articles. Sitting up all night, he worked on his publication, trying to give it “the appearance of a printed book.” A new book was published on the first of every month. “The publisher,” continues Kulish, “sometimes took the trouble to read his own and other people’s articles aloud. Everyone listened and admired. In “Zvezda,” by the way, Gogol’s story “The Tverdislavich Brothers” (imitation of stories that appeared in contemporary almanacs of that time) and various of his poems were published. All this was written in the so-called “high” style, over which all the editor’s employees fought.”

The fact that “Northern Dawn” was conceived as an imitation of “The North Star” is indirectly confirmed by I. D. Khalchinsky, Gogol’s Nezhinsky “one-trough”. He recalled that the students of the gymnasium compiled “periodic notebooks of literary attempts in imitation of the almanacs and magazines of that time.” Khalchinsky also noted that the publisher of this magazine was Gogol (together with K. M. Basili).

« B. Books».

In the list of books taken from students, several works by Voltaire stand out.

Here we find several hand-copied copies of the comedy “Woe from Wit” by Griboyedov, Pushkin’s poems “The Robber Brothers”, “Gypsies”, “Prisoner of the Caucasus” and “Bakhchisarai Fountain”, “Confession of Nalivaika” and three copies of “Voinarovsky” by Ryleev.

And finally, " D. Own student works and translations».

This section lists four dozen student works (poems, poems, articles).

Belousov attached all the materials listed in it to the “Register”.

Unfortunately, these precious materials, among which, undoubtedly, were the works of the young Gogol, have not reached us. It is very likely that Belousov did not transfer all of the materials he had to Aderkas. He could have hidden some of them - the most dangerous ones. Having looked through all the papers presented by Belousov and not finding anything “against the government” in them, Aderkas returned them to director Yasnovsky. These materials have not been preserved in the Nezhin archives.

Belousov's "Register" gives an idea of the nature and breadth of the literary interests of the gymnasium students.

It must be said that Gogol’s life in Nizhyn was full of worries and anxieties. Failures associated with the first literary experiments, joys and sorrows caused by performances of the school theater, rumors reaching the students about some disputes between the professors of the gymnasium, in addition, sad news received from home (crop failure, lack of money, illness of relatives) - all this constantly darkened Gogol's soul.

In March 1825 his father died. A sixteen-year-old boy suddenly found himself in the position of a person who should become the support of his family - his mother and five sisters. The time has come to think about your future, about your place in life.

Meanwhile, an event took place in Russia that left a huge mark on the history of the country and the echoes of which reached distant Nezhin.

After the Decembrist uprising, a violent reaction reigned in the country. Nicholas I brought down all means of violence and merciless reprisals against the people, showing at the same time, as Lenin put it, “the maximum possible and impossible in terms of such an executioner’s method.”

But the strengthening of serfdom and political terror contributed to the growth of opposition sentiments in the country. This was primarily evidenced by the continuously increasing number of peasant uprisings. From all over the empire, reports from agents about an extremely alarming “state of mind” flocked to St. Petersburg, to the head of the III department, Benckendorff. Here and there, in the most diverse strata of Russian society, “high aspirations” spontaneously broke through, which the government of Nicholas I was ultimately powerless to suppress. In the “Brief Review of Public Opinion for 1827,” presented to the Tsar by Benckendorff, it was noted with what irresistible force the thought of freedom lives in the minds of enslaved peasants: “They are waiting for their liberator... and they gave him the name Metelkina. They say to each other: " Pugachev scared the gentlemen, and Metelkin will mark them».

The annual reviews and reports of the III Department are replete with reports of mass unrest among peasants “dreaming of freedom,” as well as their merciless pacification.

The thunder of cannons on Senate Square on December 14, 1825 awakened a whole generation of progressive Russian people. The deep ulcers of feudal reality were increasingly exposed, and this could not but contribute to the process of political stratification of society. There were more and more people who understood the injustice of the autocratic, landowner system and the need for a decisive struggle against it. The memory of the Decembrists as heroic fighters and victims of autocracy was sacredly preserved in the advanced strata of Russian society.

With the defeat of Decembrism, Nicholas I hoped to radically destroy liberation ideas in Russia. But this task turned out to be impossible. “You can get rid of people, but you cannot get rid of their ideas” - the truth of these words of the Decembrist M. S. Lunin was confirmed by all the experience of the development of advanced Russian social thought in the second half of the 20s - early 30s.

The ideas of December 14 continued to inspire the liberation movement. In many places in the country, mainly in Moscow and the provinces, secret circles and societies are emerging, uniting various layers of the noble and even common intelligentsia. Members of these underground cells looked at themselves as continuers of the Decembrists’ cause. Without a sufficiently defined program and clear political goals, they heatedly discussed the lessons of December 14 and tried to outline new possible paths for the historical renewal of Russia.

Secret political circles arose in Astrakhan and Kursk, Novocherkassk and Odessa, Orenburg and among student youth in Moscow. Members of these circles, Herzen recalled in Past and Thoughts, were characterized by “a deep sense of alienation from official Russia, from the environment that surrounded them, and at the same time a desire to get out of it,” and some had “an impetuous desire to get out of it too.” . Small circles in composition became after 1825 the most characteristic form of political activity of the progressively minded intelligentsia, who intensively searched in new historical conditions for methods and means of revolutionary transformation of the country.

The ideas of the “martyrs of December 14” aroused a particularly lively response among students. In March 1826, gendarme colonel I.P. Bibikov reported from Moscow to Benckendorff: “It is necessary to focus on students and, in general, on all students in public educational institutions. Brought up for the most part in rebellious ideas and formed in principles contrary to religion, they represent a breeding ground that over time can become disastrous for the fatherland and for the legitimate government.”

One “thing” followed another. Benckendorf's public and secret agents were knocked off their feet. They were especially worried about Moscow University, which, after the defeat of Decembrism, became perhaps the main center of political freethinking in the country. Polezhaev, the circle of the Kritsky brothers, the secret society of Sungurov, then the circles of Belinsky and Herzen - this is how the baton of political freethinking, excited by the Decembrist movement, was passed on in Moscow.

No less acute political events unfolded in Ukraine, in close proximity to Nizhyn. It is curious that the Little Russian military governor, Prince Repnin, reporting to Nicholas I on the state of affairs in the region entrusted to him after the Decembrist uprising, wrote in one of his reports: “Silence and calm are preserved absolutely everywhere.” It was an obvious lie, dictated by the desire not to wash dirty linen in public. The situation in Ukraine has never been so alien to “peace and tranquility” as it was at the time when Repnin wrote this report. For centuries, the accumulated hatred of Ukrainian peasants towards their oppressors sought an outlet. The struggle against serf owners took on increasingly violent forms, especially in the Kiev and Chernihiv regions. Uprisings broke out in various places.

Similar facts, as well as the events of December 14 in St. Petersburg and the uprising of the Chernigov regiment in Ukraine that broke out almost simultaneously (December 29, 1825 - January 3, 1826), did not pass by Nezhin. Under the influence of the general political atmosphere, growing dissatisfaction with the serfdom, sentiments of political freethinking began to penetrate into the Nizhyn “Gymnasium of Higher Sciences”, which soon resulted in the “case of freethinking”, in which a significant part of the professors and students were involved. Gogol was among these students.

The main defendant in the “freethinking case” turned out to be junior professor of political science Nikolai Grigoryevich Belousov. The reactionary teachers of the gymnasium began to weave intrigues against him. The organizer of the persecution of Belousov was the stupid and ignorant professor M.V. Bilevich. He wrote slanderous reports about the order in the gymnasium, about the outrages and free-thinking of the students, and at the same time claimed that Belousov was to blame for everything. Having collected several student notebooks with notes from lectures on natural law, Bilevich presented them to the pedagogical council of the gymnasium. In the accompanying report, he pointed out that Belousov’s lectures say nothing about respect for God, for “neighbor” and that they are “full of opinions and positions that can really lead inexperienced youth into error.” Thus a high-profile case was created, which acquired a completely distinct political character. The investigation began. Professors and students of the gymnasium were summoned for interrogation.

“The Case of Freethinking” sheds light on the atmosphere that reigned in Nezhin and in which Gogol was brought up. This “case” was a kind of political echo of the events of December 14, 1825.

During the investigation into the Belousov case, it turned out that back in November 1825, “some boarders,” according to the supervisor N.N. Maslyannikov, “said that there would be changes in Russia worse than the French Revolution.” Maslyannikov cited the names of the gymnasium students who, on the eve of the Decembrist uprising, mysteriously whispered to each other, told each other rumors about the upcoming changes in Russia and at the same time sang a song:

Oh God, if you exist,

Mash all the kings with mud,

Misha, Masha, Kolya and Sasha

Put him on a stake.

Among the students singing the “outrageous” song, Maslyannikov named Gogol’s closest friends - N. Ya. Prokopovich and A. S. Danilevsky. Undoubtedly, Gogol himself was aware of this fact.

During the investigation into the “case of freethinking,” it was discovered that Belousov was not the only center of seditious ideas in the Nizhyn gymnasium. He had like-minded people: professors K.V. Shapalinsky, who at one time served as the acting director of the gymnasium, I.Ya. Landrazhin, F.I. Zinger.

Regarding this latter, one of the students testified at the investigation that he, Singer, “often replaced lectures with political reasoning.” According to another testimony, Singer asked his students to read articles condemning the decrees of the church and, in addition, “for class translations, he chose and translated various articles about revolutions in class.”

About Professor Landrazhin, one of the pupils testified that he “distributes various books for students to read, namely: the works of Voltaire, Helvetius, Montesquieu...” And according to the testimony of the former inspector of the gymnasium, Professor Moiseev, Landrazhin, “walking with the students, often sang to them “Marseillaise” "

In January 1828, Landragin invited his students to translate some Russian text into French as homework. 6th grade student Alexander Zmiev used for this purpose a poem by Kondraty Ryleev, “containing an appeal to freedom,” received shortly before from his student Martos.

Landrazhin, of course, hid this fact from the director of the gymnasium, telling Zmiev: “It’s good that it went to someone like me, a noble man; you know that such things in Vilna made several young people unhappy; We have a despotic government in Russia; it is not allowed to speak freely.”

Upon investigation, it turned out that the said poem was well known to most of the students at the gymnasium, who often recited it out loud and sang it. “It is known about this ode,” director Yasnovsky later reported, “that it passed through the hands of the students.” Zmiev himself stated during interrogation that “most of the students usually sang these poems in the gymnasium.” Rumors about “free-thinking sentiments in the “gymnasium of higher sciences” soon became common knowledge. According to Kolyshkevich’s student, he was told by an official in Chernigov that there were rumors: “It’s almost as if he, Kolyshkevich, with some accomplices and Professor Belousov will not go in a wagon.”

After some time, Benckendorf himself, the chief of gendarmes and the head of the III department, who learned about them from intelligence reports, became interested in the events in Nizhyn. In 1830, in the first expedition of the III department, a special dossier was opened “On the professors of the Nezhin Prince Bezborodko gymnasium: Shapalinsky, Belousov, Zinger and Landrazhin, who, according to the testimony of Professor Bilevich, instilled harmful rules in the students.” On January 31, 1830, Benckendorff sent a special letter to the Minister of Education, Prince Lieven, about “teaching science at the Nizhyn gymnasium.” The frightened minister immediately sent his special representative, member of the Main Board of Schools E. B. Aderkas, to Nizhyn to investigate the case on the spot.

In Nizhyn, Aderkas collected a large amount of investigative material. Based on the conclusion of Aderkas and the conclusions of the Minister of Education Lieven, Nicholas I ordered: “for the harmful influence on youth” of professors Shapalinsky, Belousov, Landrazhin and Singer “to be removed from their positions, with these circumstances entered into their passport, so that in this way they could not be anywhere in the future tolerated in the service of the educational department, and those of them who are not Russians will be sent abroad, and the Russians to the places of their homeland, placed under the supervision of the police.”

But the matter did not end there. The Nizhyn “gymnasium of higher sciences” was actually completely destroyed and was soon transformed into a physics and mathematics lyceum of a narrow specialty.

The main material for the accusation of Professor N. G. Belousov was his lectures on natural law. In the archives of the Ministry of Public Education, we found notebooks with recordings of Belousov’s lectures, belonging to thirteen students of the Nizhyn gymnasium. In 1830, Aderkas took them, among many other materials, with him to St. Petersburg.

A comparison of these notebooks leads to the conclusion that they basically go back to one common primary source. From the testimony of a number of students at the gymnasium, it is clear that the primary basis for a significant part of the notebooks were notes from Belousov’s lectures made by Gogol in the 1825–26 academic year.

N. Kukolnik, for example, testified during the investigation that one of his notebooks under the letter C was “copied from the notebooks of a 9th grade student of boarder Yanovsky (Gogol) without any additions, and these notebooks were written according to dictation from the notebook of Professor Belousov.” The puppeteer, in addition, stated that he gave Yanovsky’s notes to boarder Alexander Novokhatsky.

This circumstance was confirmed by Novokhatsky. He stated that he “had a notebook of the history of natural law and natural law itself, copied by order of Professor Belousov from the beginning of the academic year from the notes of the previous course, belonging to the boarder Yanovsky and given to Kukolnik for use.”

On November 3, 1827, testimony was taken from Gogol. The interrogation protocol states that Yanovsky “confirmed Novokhatsky’s testimony that he gave the notebook of the history of natural law and the most natural law to Kukolnik for use.”

Gogol's notebook on natural law passed through the hands of students. Characteristic is Novokhatsky’s remark that his notebook was copied from Yanovsky’s notes “on the orders of Professor Belousov.” It must be assumed that Gogol's notebook was familiar to Belousov and was recognized as the most reliable recording of his lectures.

Gogol's manuscript has not survived. But among the student notes that we discovered in the archives of the Ministry of Public Education, there is that same Kukolnik notebook under the letter C, which “without any additions” was copied from Gogol’s notebook. The summary consists of two parts: the history of natural law and the law itself, i.e. its theory. The most interesting part is the second.

Characterizing natural law, Belousov sees in it the most perfect and reasonable basis of the social structure. Evidence of natural law must be drawn from reason. It is not faith in divine institutions, but the omnipotence of the human mind that is the “purest source” of the laws of natural law. State laws are morally binding for a person only insofar as they do not contradict the laws of nature itself. “A person has the right to his own face,” says Belousov, “that is, he has the right to be the way nature formed his soul.” This is where the idea of “inviolability of the face” comes from, i.e. the freedom and independence of the human person.

These provisions of Belousov caused sharp criticism from the teacher of law at the Nizhyn gymnasium, Archpriest Volynsky, who saw in them the opportunity for students to assimilate views leading “to the error of materialism” and the denial of “all obedience to the law.”

Belousov's lectures were imbued with the spirit of denial of class inequality and class privileges; Belousov defends the principle of equality of people. “All innate rights,” he says, “are in absolute equality for all people.” Volynsky found such a conclusion “too free,” because equality of rights, in his opinion, can only be discussed “with regard to one animal instinct.”

Some ideas of natural law are given a very bold interpretation by Belousov for his time. A number of his formulas are associated with the statements of the Decembrists. Let us recall, for example, the dialogue from “A Curious Conversation” by Nikita Muravyov:

« Question. Am I free to do everything?

Reply. You are free to do everything that is not harmful to others. It's your right.

Question. What if someone oppresses?

Reply. This will be violence against you, which you have the right to resist.”

Natural law was presented by Belousov in an abstract philosophical, theoretical way, but many of the provisions of his lectures were easily applied to Russian reality. For example, when he said that " no one in the state should be governed autocratically”, then behind this brief entry in a student’s notebook we feel the position of a person indignant against the “autocratically governed” serfdom state.

The content of Belousov's lectures allows us to conclude that in his views there were echoes, of course very weakened, timid, of some general ideas of the Decembrists and Radishchev. Although Radishchev’s name is not mentioned anywhere in the materials of the “freethinking case,” there is reason to assume that this name was known to Belousov. A man of serious and versatile knowledge, who had a negative attitude towards feudal reality, Belousov could not pass by such a book as “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow.” One of the provisions of Belousov’s lectures - that the offended has the right to reward and determines the measure of reward - in its general form echoes the ideas of the Decembrists and the thoughts of Radishchev, in whom this thesis, of course, is imbued with much deeper political content.

In many of Radishchev’s works, the idea of a person’s natural right to take revenge for an insult caused to him is defended. Talking in “The Life of Fyodor Vasilyevich Ushakov” about the insult inflicted on Nasakin, Radishchev notes that, according to the unanimous decision of the students, Major Bokum “had to make satisfaction for Nasakin’s insult.” It is remarkable that this decision is justified by Radishchev by the laws of natural law: “Without the slightest obstacle in his procession, a person in a natural position, when committing an insult, drawn by the feeling of his safety, awakens to repel the insult.” Radishchev returns to this thesis very often in his “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow.” Proving, for example, the innocence of the peasants who killed the cruel assessor, the writer says that they correctly determined the punishment for “their enemy,” for the citizen is obliged to use the “natural right of defense” that belongs to him; if the civil law does not punish the offender, then the offended one himself, “have enough strength, and take revenge on him for the offense he has committed” (chapter “Zaitsovo”). Elsewhere, reflecting on the terrible cruelties committed by landowners against their serfs, Radishchev remarks: “Do you know what is written in the primary code in everyone’s heart? If I hit someone, he can hit me too” (chapter of “Lyuban”).

The idea of a person’s natural right to freedom and to take revenge for the insult caused to him acquires a pronounced socio-political and revolutionary interpretation from Radishchev. Of course, we will not find anything like this in Belousov. His lectures were of a completely different nature.

Having adopted some Enlightenment ideas, he developed them only in an abstract theoretical sense, without drawing any political conclusions from this in relation to specific problems of Russian reality.

This was the fundamental difference between Belousov and the Decembrists, and even more so from Radishchev.