The first Russian field marshal. Portraits of field marshals of the Russian army. Junkers and military districts

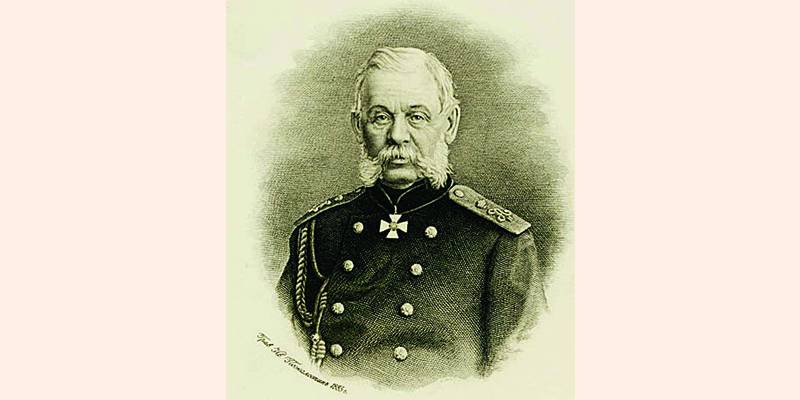

200 years ago, the last Field Marshal of the Russian Empire, Dmitry Milyutin, was born - the largest reformer of the Russian army.

Dmitry Alekseevich Milyutin (1816–1912)

It is to him that Russia owes the introduction of universal conscription. For its time, this was a real revolution in the principles of army recruitment. Before Milyutin, the Russian army was class-based, its basis was made up of recruits - soldiers recruited from the burghers and peasants by lot. Now everyone was called into it - regardless of origin, nobility and wealth: the defense of the Fatherland became truly the sacred duty of everyone. However, the Field Marshal General became famous not only for this...

TAILCOA OR MUNIDIRA?

Dmitry Milyutin was born on June 28 (July 10), 1816 in Moscow. On his father's side, he belonged to the middle-class nobles, whose surname originated from the popular Serbian name Milutin. The father of the future field marshal, Alexei Mikhailovich, inherited a factory and estates, burdened with huge debts, which he tried unsuccessfully to pay off all his life. His mother, Elizaveta Dmitrievna, née Kiselyova, came from an old eminent noble family; Dmitry Milyutin’s uncle was Infantry General Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselyov, a member of the State Council, Minister of State Property, and later the Russian Ambassador to France.

Alexey Mikhailovich Milyutin was interested in the exact sciences, was a member of the Moscow Society of Natural Scientists at the university, was the author of a number of books and articles, and Elizaveta Dmitrievna knew foreign and Russian literature very well, loved painting and music. Since 1829, Dmitry studied at the Moscow University Noble Boarding School, which was not much inferior to the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, and Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselev paid for his education. The first scientific works of the future reformer of the Russian army date back to this time. He compiled an “Experience in a Literary Dictionary” and synchronic tables on, and at the age of 14–15 years he wrote a “Guide to Taking Plans Using Mathematics,” which received positive reviews in two reputable magazines.

In 1832, Dmitry Milyutin graduated from the boarding school, receiving the right to the rank of tenth grade in the Table of Ranks and a silver medal for academic success. He was faced with a question that was significant for a young nobleman: a tailcoat or a uniform, a civil or military path? In 1833, he went to St. Petersburg and, on the advice of his uncle, became a non-commissioned officer in the 1st Guards Artillery Brigade. He had 50 years of military service ahead of him. Six months later, Milyutin became an ensign, but the daily marching under the supervision of the grand dukes was so exhausting and dull that he even began to think about changing his profession. Fortunately, in 1835 he managed to enter the Imperial Military Academy, which trained General Staff officers and teachers for military educational institutions.

At the end of 1836, Dmitry Milyutin was released from the academy with a silver medal (at the final exams he received 552 points out of 560 possible), promoted to lieutenant and assigned to the Guards General Staff. But the guardsman’s salary alone was clearly not enough for a decent living in the capital, even if, as Dmitry Alekseevich did, he eschewed the entertainment of the golden officer youth. So I had to constantly earn extra money by translating and writing articles in various periodicals.

PROFESSOR MILITARY ACADEMY

In 1839, at his request, Milyutin was sent to the Caucasus. Service in the Separate Caucasian Corps was at that time not just a necessary military practice, but also a significant step for a successful career. Milyutin developed a number of operations against the highlanders, and he himself took part in the campaign against the village of Akhulgo, the then capital of Shamil. During this expedition he was wounded, but remained in service.

The following year, Milyutin was appointed to the post of quartermaster of the 3rd Guards Infantry Division, and in 1843 - chief quartermaster of the troops of the Caucasian Line and the Black Sea Region. In 1845, on the recommendation of Prince Alexander Baryatinsky, close to the heir to the throne, he was recalled to the disposal of the Minister of War, and at the same time Milyutin was elected professor at the Military Academy. In the description given to him by Baryatinsky, it was noted that he was diligent, of excellent abilities and intelligence, exemplary morality, and thrifty in the household.

Milyutin did not give up his scientific studies either. In 1847–1848, his two-volume work “First Experiments in Military Statistics” was published, and in 1852–1853, his professionally completed “History of the War between Russia and France during the reign of Emperor Paul I in 1799” in five volumes.

The last work was prepared by two substantive articles written by him back in the 1840s: “A.V. Suvorov as a commander" and "Russian commanders of the 18th century." “The History of the War between Russia and France,” immediately after its publication, translated into German and French, brought the author the Demidov Prize of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Soon after this he was elected a corresponding member of the academy.

In 1854, Milyutin, already a major general, became the clerk of the Special Committee on measures to protect the shores of the Baltic Sea, which was formed under the chairmanship of the heir to the throne, Grand Duke Alexander Nikolaevich. This is how the service brought together the future Tsar-reformer Alexander II and one of his most effective associates in developing reforms...

MILYUTIN'S NOTE

In December 1855, when the Crimean War was so difficult for Russia, Minister of War Vasily Dolgorukov asked Milyutin to draw up a note on the state of affairs in the army. He carried out the assignment, especially noting that the number of armed forces of the Russian Empire is large, but the bulk of the troops are made up of untrained recruits and militias, that there are not enough competent officers, which makes new recruitments pointless.

Seeing off a new recruit. Hood. I.E. Repin. 1879

Milyutin wrote that a further increase in the army is impossible for economic reasons, since industry is unable to provide it with everything necessary, and imports from abroad are difficult due to the boycott declared by European countries on Russia. The problems associated with the lack of gunpowder, food, rifles and artillery pieces, not to mention the disastrous state of transport routes, were obvious. The bitter conclusions of the note largely influenced the decision of the members of the meeting and the youngest Tsar Alexander II to begin peace negotiations (the Paris Peace Treaty was signed in March 1856).

In 1856, Milyutin was again sent to the Caucasus, where he took the position of chief of staff of the Separate Caucasian Corps (soon reorganized into the Caucasian Army), but already in 1860 the emperor appointed him comrade (deputy) minister of war. The new head of the military department, Nikolai Sukhozanet, seeing Milyutin as a real competitor, tried to remove his deputy from important matters, and then Dmitry Alekseevich even had thoughts about resigning to engage exclusively in teaching and scientific activities. Everything changed suddenly. Sukhozanet was sent to Poland, and the management of the ministry was entrusted to Milyutin.

Count Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselev (1788–1872) - infantry general, minister of state property in 1837–1856, uncle of D.A. Milyutina

His first steps in his new post were met with universal approval: the number of ministry officials was reduced by a thousand people, and the number of outgoing papers by 45%.

ON THE WAY TO A NEW ARMY

On January 15, 1862 (less than two months after assuming a high position), Milyutin presented Alexander II with a most comprehensive report, which, in essence, was a program for sweeping reforms in the Russian army. The report contained 10 points: the number of troops, their recruitment, staffing and management, drill training, military personnel, military judicial unit, food supply, military medical unit, artillery, engineering units.

Preparing a plan for military reform required Milyutin not only to exert himself (he worked 16 hours a day on the report), but also a fair amount of courage. The minister encroached upon the archaic and rather compromised itself in the Crimean War, but still the legendary class-patriarchal army, steeped in heroic legends, which remembered both the “times of Ochakovo” and Borodino and the capitulation of Paris. However, Milyutin decided to take this risky step. Or rather, a whole series of steps, since the large-scale reform of the Russian armed forces under his leadership lasted for almost 14 years.

Training of recruits in Nikolaev time. Drawing by A. Vasiliev from the book by N. Schilder “Emperor Nicholas I. His life and reign”

First of all, he proceeded from the principle of the greatest reduction in the size of the army in peacetime, with the possibility of its maximum increase in case of war. Milyutin understood perfectly well that no one would allow him to immediately change the recruitment system, and therefore proposed to increase the number of recruits recruited annually to 125 thousand, subject to the soldiers being discharged “on leave” in the seventh or eighth year of service. As a result, over seven years the size of the army decreased by 450–500 thousand people, but a trained reserve of 750 thousand people was formed. It is easy to see that formally this was not a reduction in service life, but merely the provision of temporary “leave” to the soldiers - a deception, so to speak, for the good of the cause.

JUNKERS AND MILITARY DISTRICTS

No less pressing was the issue of officer training. Back in 1840, Milyutin wrote:

“Our officers are formed exactly like parrots. Before they are produced, they are kept in a cage, and they are constantly told: “Ass, turn to the left all around!”, and the ass repeats: “All around to the left.” When the butt reaches the point where it has firmly memorized all these words and, moreover, will be able to stand on one paw... they put on epaulettes for him, open the cage, and he flies out of it with joy, with hatred for his cage and his former mentors.”

In the mid-1860s, military educational institutions, at the request of Milyutin, were transferred to the subordination of the Ministry of War. Cadet corps, renamed military gymnasiums, became secondary specialized educational institutions. Their graduates entered military schools, which trained about 600 officers annually. This turned out to be clearly not enough to replenish the command staff of the army, and a decision was made to create cadet schools, upon admission to which knowledge of approximately four classes of a regular gymnasium was required. Such schools graduated about 1,500 more officers per year. Higher military education was represented by the Artillery, Engineering and Military Law Academies, as well as the Academy of the General Staff (formerly the Imperial Military Academy).

Based on the new regulations on combat infantry service, issued in the mid-1860s, the training of soldiers also changed. Milyutin revived Suvorov's principle - to pay attention only to what is really necessary for the rank and file to serve: physical and drill training, shooting and tactical tricks. In order to spread literacy among the rank and file, soldiers' schools were organized, regimental and company libraries were created, and special periodicals appeared - “Soldier's Conversation” and “Reading for Soldiers.”

Discussions about the need to rearm the infantry have been going on since the late 1850s. At first, there was talk of remaking old guns in a new way, and only 10 years later, at the end of the 1860s, it was decided to give preference to the Berdan No. 2 rifle.

A little earlier, according to the “Regulations” of 1864, Russia was divided into 15 military districts. The district departments (artillery, engineering, quartermaster and medical) were subordinate, on the one hand, to the head of the district, and on the other, to the corresponding main departments of the War Ministry. This system eliminated excessive centralization of military command and control, provided operational leadership on the ground and the ability to quickly mobilize armed forces.

The next urgent step in the reorganization of the army was to be the introduction of universal conscription, as well as enhanced training of officers and increased spending on material support for the army.

However, after Dmitry Karakozov shot the monarch on April 4, 1866, the position of the conservatives noticeably strengthened. However, it was not only about the assassination attempt on the Tsar. It must be borne in mind that every decision to reorganize the armed forces required a number of innovations. Thus, the creation of military districts entailed the “Regulations on the establishment of quartermaster warehouses”, “Regulations on the management of local troops”, “Regulations on the organization of fortress artillery”, “Regulations on the management of the inspector general of cavalry”, “Regulations on the organization of artillery parks” and etc. And each such change inevitably aggravated the struggle between the minister-reformer and his opponents.

MILITARY MINISTERS OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

A.A. Arakcheev

M.B. Barclay de Tolly

From the creation of the Military Ministry of the Russian Empire in 1802 until the overthrow of the autocracy in February 1917, this department was led by 19 people, including such notable figures as Alexei Arakcheev, Mikhail Barclay de Tolly and Dmitry Milyutin.

The latter held the post of minister the longest - as much as 20 years, from 1861 to 1881. The last Minister of War of Tsarist Russia, Mikhail Belyaev, held this position the least - from January 3 to March 1, 1917.

YES. Milyutin

M.A. Belyaev

THE BATTLE FOR UNIVERSAL CONSTITUTION

It is not surprising that from the end of 1866 the most popular and discussed rumor was the resignation of Milyutin. He was accused of destroying the army, famous for its victories, of democratizing its orders, which led to a decline in the authority of officers and to anarchy, and of colossal expenses for the military department. It should be noted that the ministry’s budget was indeed exceeded by 35.5 million rubles in 1863 alone. However, Milyutin's opponents proposed cutting the amounts allocated to the military department so much that it would be necessary to reduce the armed forces by half, stopping recruitment altogether. In response, the minister presented calculations from which it followed that France spends 183 rubles per year on each soldier, Prussia - 80, and Russia - 75 rubles. In other words, the Russian army turned out to be the cheapest of all the armies of the great powers.

The most important battles for Milyutin unfolded at the end of 1872 - beginning of 1873, when the draft Charter on universal conscription was discussed. The opponents of this crown of military reforms were led by field marshals Alexander Baryatinsky and Fyodor Berg, the Minister of Public Education, and since 1882 the Minister of Internal Affairs Dmitry Tolstoy, the Grand Dukes Mikhail Nikolaevich and Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder, generals Rostislav Fadeev and Mikhail Chernyaev and the chief of gendarmes Pyotr Shuvalov. And behind them loomed the figure of the ambassador in St. Petersburg of the newly created German Empire, Heinrich Reiss, who received instructions personally from Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The antagonists of the reforms, having obtained permission to get acquainted with the papers of the War Ministry, regularly wrote notes full of lies, which immediately appeared in the newspapers.

All-class military service. Jews in one of the military presences in western Russia. Engraving by A. Zubchaninov from a drawing by G. Broling

The emperor took a wait-and-see attitude in these battles, not daring to take either side. He either established a commission to find ways to reduce military spending under the chairmanship of Baryatinsky and supported the idea of replacing military districts with 14 armies, or leaned in favor of Milyutin, who argued that it was necessary either to cancel everything that had been done in the army in the 1860s, or to firmly go to end. Naval Minister Nikolai Krabbe told how the discussion of the issue of universal conscription took place in the State Council:

“Today Dmitry Alekseevich was unrecognizable. He did not expect attacks, but he rushed at the enemy, so much so that it was scary for the stranger... With his teeth in the throat and through the ridge. Quite a lion. Our old people left scared.”

DURING THE MILITARY REFORM, IT WAS MANAGED TO CREATE A STRONG SYSTEM OF ARMY MANAGEMENT AND OFFICER CORPS TRAINING, to establish a new principle of its recruitment, to rearm the infantry and artillery

Finally, on January 1, 1874, the Charter on all-class military service was approved, and the highest rescript addressed to the Minister of War said:

“With your hard work in this matter and your enlightened view of it, you have rendered a service to the state, which I take the special pleasure of witnessing and for which I express my sincere gratitude to you.”

Thus, in the course of military reforms, it was possible to create a coherent system of army management and training of the officer corps, establish a new principle for its recruitment, largely revive Suvorov’s methods of tactical training of soldiers and officers, increase their cultural level, and rearm the infantry and artillery.

TRIAL OF WAR

Milyutin and his antagonists greeted the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878 with completely opposite feelings. The minister was worried because the army reform was just gaining momentum and there was still a lot to be done. And his opponents hoped that the war would reveal the failure of the reform and force the monarch to listen to their words.

In general, events in the Balkans confirmed Milyutin was right: the army passed the test of war with honor. For the minister himself, the real test of strength was the siege of Plevna, or more precisely, what happened after the third unsuccessful assault on the fortress on August 30, 1877. The Commander-in-Chief of the Danube Army, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Elder, shocked by the failure, decided to lift the siege of Plevna - a key point of Turkish defense in Northern Bulgaria - and withdraw troops beyond the Danube.

Presentation of the captive Osman Pasha to Alexander II in Plevna. Hood. N. Dmitriev-Orenburgsky. 1887. Minister D.A. is depicted among the highest military officials of Russia. Milyutin (far right)

Milyutin objected to such a step, explaining that reinforcements should soon approach the Russian army, and the position of the Turks in Plevna was far from brilliant. But to his objections the Grand Duke answered irritably:

“If you think it’s possible, then take command, and I ask you to fire me.”

It is difficult to say how events would have developed further if Alexander II had not been present at the theater of military operations. He listened to the minister’s arguments, and after a siege organized by the hero of Sevastopol, General Eduard Totleben, Plevna fell on November 28, 1877. Addressing the retinue, the sovereign then announced:

“Know, gentlemen, that we owe today and the fact that we are here to Dmitry Alekseevich: he alone at the military council after August 30 insisted on not retreating from Plevna.”

The Minister of War was awarded the Order of St. George, II degree, which was an exceptional case, since he did not have either the III or IV degrees of this order. Milyutin was elevated to the dignity of count, but the most important thing was that after the Berlin Congress, which was tragic for Russia, he became not only one of the ministers closest to the tsar, but also the de facto head of the foreign policy department. Comrade (Deputy) Minister of Foreign Affairs Nikolai Girs henceforth coordinated all fundamental issues with him. Our hero's longtime enemy Bismarck wrote to German Emperor Wilhelm I:

"The minister who now has decisive influence over Alexander II is Milyutin."

The Emperor of Germany even asked his Russian brother to remove Milyutin from the post of Minister of War. Alexander replied that he would be happy to fulfill the request, but at the same time he would appoint Dmitry Alekseevich to the post of head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Berlin hastened to abandon his offer. At the end of 1879, Milyutin took an active part in negotiations regarding the conclusion of the “Union of Three Emperors” (Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany). The Minister of War advocated an active policy of the Russian Empire in Central Asia, advised to switch from supporting Alexander Battenberg in Bulgaria, giving preference to the Montenegrin Bozidar Petrovich.

ZAKHAROVA L.G. Dmitry Alekseevich Milyutin, his time and his memoirs // Milyutin D.A. Memories. 1816–1843. M., 1997.

***

PETELIN V.V. The life of Count Dmitry Milyutin. M., 2011.

AFTER THE REFORM

At the same time, in 1879, Milyutin boldly asserted: “It is impossible not to admit that our entire state structure requires radical reform from bottom to top.” He strongly supported the actions of Mikhail Loris-Melikov (by the way, it was Milyutin who proposed the general’s candidacy for the post of All-Russian dictator), which included lowering the redemption payments of peasants, abolishing the Third Department, expanding the competence of zemstvos and city dumas, and establishing general representation in the highest bodies of power. However, the time for reform was ending. On March 8, 1881, a week after the assassination of the emperor by the Narodnaya Volya, Milyutin gave his last battle to the conservatives who opposed the “constitutional” project of Loris-Melikov, approved by Alexander II. And he lost this battle: according to Alexander III, the country did not need reforms, but calming...

“IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO NOT RECOGNIZE that our entire state structure requires radical reform from top to bottom.”

On May 21 of the same year, Milyutin resigned, rejecting the new monarch’s offer to become governor of the Caucasus. The following entry appeared in his diary:

“In the present state of affairs, with the current figures in the highest government, my position in St. Petersburg, even as a simple, unresponsive witness, would be unbearable and humiliating.”

When he retired, Dmitry Alekseevich received portraits of Alexander II and Alexander III, showered with diamonds, as a gift, and in 1904, the same portraits of Nicholas I and Nicholas II. Milyutin was awarded all Russian orders, including the diamond insignia of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called, and in 1898, during the celebrations in honor of the opening of the monument to Alexander II in Moscow, he was promoted to field marshal general. Living in Crimea, on the Simeiz estate, he remained faithful to the old motto:

“You don’t need to rest at all, doing nothing. You just need to change jobs, and that’s enough.”

In Simeiz, Dmitry Alekseevich organized the diary entries that he kept from 1873 to 1899, and wrote wonderful multi-volume memoirs. He closely followed the course of the Russo-Japanese War and the events of the First Russian Revolution.

He lived a long time. Fate seemed to reward him for not giving it to his brothers, because Alexey Alekseevich Milyutin passed away at the age of 10, Vladimir at 29, Nikolai at 53, Boris at 55. Dmitry Alekseevich died in Crimea at the age of 96, three days after the death of his wife. He was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow next to his brother Nikolai. During the Soviet years, the burial place of the last field marshal of the empire was lost...

Dmitry Milyutin left almost his entire fortune to the army, donated a rich library to his native Military Academy, and bequeathed his estate in Crimea to the Russian Red Cross.

Ctrl Enter

Noticed osh Y bku Select text and click Ctrl+Enter

Boris Petrovich's youth as a representative of the noble nobility was no different from his peers: at the age of 13, he was granted a position as a steward, accompanied Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich on trips to monasteries and villages near Moscow, and stood with a bell at the throne at ceremonial receptions. The position of steward ensured closeness to the throne and opened up broad prospects for promotion in ranks and positions. In 1679, military service began for Sheremetev. He was appointed comrade voivode in the Great Regiment, and two years later - voivode of one of the ranks. In 1682, with the accession to the throne of Tsars Ivan and Peter Alekseevich, Sheremetev was granted a boyar status.In 1686, the embassy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth arrived in Moscow to conclude a peace treaty. Boyar Sheremetev was also among the four members of the Russian embassy. Under the terms of the agreement, Kyiv, Smolensk, Left Bank Ukraine, Zaporozhye and Seversk land with Chernigov and Starodub were finally assigned to Russia. The treaty also served as the basis for the Russian-Polish alliance in the Northern War. As a reward for the successful conclusion of the “Eternal Peace”, Boris Petrovich was awarded a silver cup, a satin caftan and 4 thousand rubles. In the summer of the same year, Sheremetev went with the Russian embassy to Poland to ratify the treaty, and then to Vienna to conclude a military alliance against the Turks. However, the Austrian Emperor Leopold I decided not to burden himself with allied obligations; the negotiations did not lead to the desired results.

After his return, Boris Petrovich is appointed governor of Belgorod. In 1688, he took part in the Crimean campaign of Prince V.V. Golitsyn. However, the future field marshal's first combat experience was unsuccessful. In the battles in the Black and Green Valleys, the detachment under his command was crushed by the Tatars.

In the struggle for power between Peter and Sophia, Sheremetev took Peter's side, but for many years he was not called to court, remaining the Belgorod governor. In the first Azov campaign of 1695, he participated in a theater of military operations remote from Azov, commanding troops that were supposed to divert Turkey's attention from the main direction of the Russian offensive. Peter I instructed Sheremetev to form a 120,000-strong army, which was supposed to go to the lower reaches of the Dnieper and fetter the actions of the Crimean Tatars. In the first year of the war, after a long siege, four fortified Turkish cities surrendered to Sheremetev (including Kizy-Kermen on the Dnieper). However, he did not reach Crimea and returned with troops to Ukraine, although almost the entire Tatar army was near Azov at that time. With the end of the Azov campaigns in 1696, Sheremetev returned to Belgorod.

In 1697, the Great Embassy headed by Peter I went to Europe. Sheremetev was also part of the embassy. From the king he received messages to Emperor Leopold I, Pope Innocent XII, the Doge of Venice and the Grand Master of the Order of Malta. The purpose of the visits was to conclude an anti-Turkish alliance, but it was not successful. At the same time, Boris Petrovich was given high honors. So, the Master of the Order placed the Maltese Commander's Cross on him, thereby accepting him as a knight. In the history of Russia, this was the first time a foreign order was awarded to a Russian.

By the end of the 17th century. Sweden achieved significant power. The Western powers, rightly fearing her aggressive aspirations, willingly entered into an alliance against her. In addition to Russia, the anti-Swedish alliance included Denmark and Saxony. This balance of power meant a sharp turn in Russian foreign policy - instead of a struggle for access to the Black Sea, there was a struggle for the Baltic coast and for the return of lands seized by Sweden at the beginning of the 17th century. In the summer of 1699, the Northern Alliance was concluded in Moscow.

The main theater of military operations was to be Ingria (the coast of the Gulf of Finland). The primary task was to capture the Narva fortress (Old Russian Rugodev) and the entire course of the Narova River. Boris Petrovich is entrusted with the formation of regiments of the noble militia. In September 1700, with a 6,000-strong detachment of noble cavalry, Sheremetev reached Wesenberg, but without engaging in battle, he retreated to the main Russian forces near Narva. The Swedish king Charles XII with a 30,000-strong army approached the fortress in November. On November 19, the Swedes launched an offensive. Their attack was unexpected for the Russians. At the very beginning of the battle, foreigners who were in Russian service went over to the enemy’s side. Only the Semenovsky and Preobrazhensky regiments stubbornly held out for several hours. Sheremetev's cavalry was crushed by the Swedes. In the battle of Narva, the Russian army lost up to 6 thousand people and 145 guns. Swedes' losses amounted to 2 thousand people.

After this battle, Charles XII directed all his efforts against Saxony, considering it his main enemy (Denmark was withdrawn from the war at the beginning of 1700). The corps of General V.A. was left in the Baltic states. Schlippenbach, who was entrusted with the defense of the border regions, as well as the capture of Gdov, Pechory, and in the future Pskov and Novgorod. The Swedish king had a low opinion of the combat effectiveness of the Russian regiments and did not consider it necessary to keep a large number of troops against them.

In June 1701, Boris Petrovich was appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian troops in the Baltic states. The king ordered him, without getting involved in major battles, to send cavalry detachments to areas occupied by the enemy in order to destroy the food and fodder of the Swedes, and to train the troops to fight a trained enemy. In November 1701, a campaign to Livonia was announced. And already in December, troops under the command of Sheremetev won their first victory over the Swedes at Erestfera. Against Schlippenbach's 7,000-strong detachment, 10,000 cavalry and 8,000 infantry with 16 guns acted. Initially, the battle was not entirely successful for the Russians, since only dragoons took part in it. Finding themselves without the support of infantry and artillery, which did not arrive in time to the battlefield, the dragoon regiments were scattered by enemy grapeshot. However, the approaching infantry and artillery dramatically changed the course of the battle. After a 5-hour battle, the Swedes began to flee. In the hands of the Russians there were 150 prisoners, 16 guns, as well as provisions and fodder. Assessing the significance of this victory, the tsar wrote: “We have reached the point where we can defeat the Swedes; so far we have fought two against one, but soon we will begin to defeat them with equal numbers.”

For this victory, Sheremetev was awarded the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called with a gold chain and diamonds and was elevated to the rank of Field Marshal. In June 1702, he defeated the main forces of Schlippenbach at Hummelshof. As at Erestfer, the Swedish cavalry, unable to withstand the pressure, fled, disrupting the ranks of its own infantry, dooming it to destruction. The field marshal’s success is again noted by Peter: “We are extremely grateful for your efforts.” In the same year, the fortresses of Marienburg and Noteburg (Old Russian Oreshek) were taken, and the next year Nyenschanz, Yamburg and others were taken. Livonia and Ingria were completely in the hands of the Russians. In Estland, Wesenberg was taken by storm, and then (in 1704) Dorpat. The Tsar deservedly recognized Boris Petrovich as the first winner of the Swedes.

In the summer of 1705, an uprising broke out in the south of Russia, in Astrakhan, led by Streltsy, who were mostly sent there after Streltsy riots in Moscow and other cities. Sheremetev is sent to suppress the uprising. In March 1706, his troops approached the city. After the bombing of Astrakhan, the archers surrendered. “For which your labor,” the king wrote, “the Lord God will pay you, and we will not leave you.” Sheremetev was the first in Russia to be awarded the title of count, received 2,400 households and 7 thousand rubles.

At the end of 1706, Boris Petrovich again took command of the troops operating against the Swedes. The tactics of the Russians, who were expecting a Swedish invasion, boiled down to the following: without accepting a general battle, retreat deep into Russia, acting on the flanks and behind the enemy’s rear. By this time, Charles XII had managed to deprive Augustus II of the Polish crown and place it on his protege Stanislav Leszczynski, as well as force Augustus to break allied relations with Russia. In December 1707, Charles left Saxony. The Russian army of up to 60 thousand people, the command of which the tsar entrusted to Sheremetev, was retreating to the east.

From the beginning of April 1709, the attention of Charles XII was focused on Poltava. The capture of this fortress made it possible to stabilize communications with the Crimea and Poland, where significant Swedish forces were located. And besides, the king would have a road from the south to Moscow. The Tsar ordered Boris Petrovich to move to Poltava to unite with A.D.’s troops located there. Menshikov and thereby deprive the Swedes of the opportunity to defeat the Russian troops piecemeal. At the end of May, Sheremetev arrived near Poltava and immediately assumed the duties of commander-in-chief. But during the battle he was commander-in-chief only formally, while the king led all actions. While touring the troops before the battle, Peter turned to Sheremetev: “Mr. Field Marshal! I entrust you with my army and I hope that in commanding it you will act in accordance with the instructions given to you...”. Sheremetev did not take an active part in the battle, but the tsar was pleased with the actions of the field marshal: Boris Petrovich was first on the award list of senior officers.

In July, he, at the head of infantry and a small detachment of cavalry, was sent by the tsar to the Baltic states. The immediate task is to capture Riga, under whose walls the troops arrived in October. The Tsar instructed Sheremetev to take Riga not by storm, but by siege, believing that victory would be achieved at the cost of minimal losses. But the raging plague epidemic claimed the lives of almost 10 thousand Russian soldiers. Nevertheless, the bombing of the city did not stop. The capitulation of Riga was signed on July 4, 1710.

In December 1710, Turkey declared war on Russia, and Peter ordered the troops located in the Baltic states to move south. A poorly prepared campaign, a lack of food and inconsistency in the actions of the Russian command put the army in a difficult situation. Russian regiments were surrounded in the area of the river. Prut many times outnumbered the Turkish-Tatar troops. However, the Turks did not impose a general battle on the Russians, and on July 12 a peace was signed, according to which Azov was returned to Turkey. As a guarantee of fulfillment of Russia's obligations, Chancellor P.P. remained hostage to the Turks. Shafirov and son B.P. Sheremeteva Mikhail.

Upon returning from the Prut campaign, Boris Petrovich commanded troops in Ukraine and Poland. In 1714, the Tsar sent Sheremetev to Pomerania. Gradually, the tsar began to lose confidence in the field marshal, suspecting him of sympathy for Tsarevich Alexei. 127 people signed the death sentence for Peter’s son. Sheremetev's signature was missing.

In December 1716 he was relieved of command of the army. The field marshal asked the king to give him a position more suitable for his age. Peter wanted to appoint him governor-general of the lands in Estland, Livonia and Ingria. But the appointment did not take place: on February 17, 1719, Boris Petrovich died.

Portraits of the highest officials of the Russian Empire. Field Marshals General.PORTRAIT

Chin Field Marshal General introduced by Peter I in 1699 instead of the existing position of “Chief Governor of a Large Regiment”. The rank was also established Field Marshal Lieutenant General, as a deputy field marshal, but after 1707 it was not assigned to anyone.

In 1722, the rank of field marshal was introduced into the Table of Ranks as a military rank of 1st class. It was awarded not necessarily for military merit, but also for long-term public service or as a sign of royal favor. Several foreigners, not being in Russian service, were awarded this rank as an honorary title.

In total, 65 people were awarded this rank (including 2 field marshal-lieutenant generals).

The first 12 people were granted by Emperors Peter I, Catherine I and Peter II:

01. gr. Golovin Fedor Alekseevich (1650-1706) from 1700

Copy of Ivan Spring from an unknown original of the early 18th century. State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg.

02. grc. Croagh Karl Eugen (1651-1702) from 1700

No portrait found. There is only a photograph of his preserved body, which until 1863 lay in a glass coffin in the Revel (Tallinn) Church of St. Nicholas.

03. gr. Sheremetev Boris Petrovich (1652-1719) from 1701

Ostankino Palace Museum.

04. Ogilvy George Benedict (1651-1710) from 1702 (Field Marshal-Lieutenant General)

Engraving from an unknown 18th century original. Source: Beketov’s book “Collection of portraits of Russians famous for their deeds...”, 1821.

05. Goltz Heinrich (1648-1725) from 1707 (Field Marshal-Lieutenant General)

06. St. book Menshikov Alexander Danilovich (1673-1729) from 1709, generalissimo from 1727.

Unknown artist of the 18th century. Museum "Kuskovo Estate".

07. book. Repnin Anikita Ivanovich (1668-1726) from 1724

Portrait of work unknown. artist of the early 18th century. Poltava Museum.

08. book. Golitsyn Mikhail Mikhailovich (1675-1730) from 1725

Unknown artist of the 18th century.

09. gr. Sapega Jan Casimir (1675-1730), from 1726 (Great Hetman of Lithuania in 1708-1709)

Unknown artist of the 18th century. Rawicz Palace, Poland.

10. gr. Bruce Yakov Vilimovich (1670-1735) from 1726

Unknown artist of the 18th century.

11. book. Dolgorukov Vasily Vladimirovich (1667-1746) from 1728

Portrait by Groot. 1740s. State Tretyakov Gallery.

12. book. Trubetskoy Ivan Yurievich (1667-1750) from 1728

Unknown artist of the 18th century. State Tretyakov Gallery.

Field Marshals promoted to the rank by Empresses Anna Ioannovna, Elizaveta Petrovna and Emperor Peter III:

13 gr. Minich Burchard Christopher (1683-1767) from 1732

Portrait by Buchholz. 1764. State Russian Museum.

14 gr. Lassi Petr Petrovich (1678-1751) from 1736

Unknown artist of the 18th century. Source M. Borodkin "History of Finland" vol. 2 1909

15 Ave. Ludwig Wilhelm of Hesse-Homburg (1705-1745) from 1742

Unknown artist ser. XVIII century. Private collection.

16 books Trubetskoy Nikita Yuryevich (1700-1767) from 1756

Unknown artist ser. XVIII century. State Museum of Art of Georgia.

17 gr. Buturlin Alexander Borisovich (1694-1767) from 1756

copy of the 19th century from a painting by an unknown artist from the mid-18th century. Museum of the History of St. Petersburg.

18 gr. Razumovsky Alexey Grigorievich (1709-1771) from 1756

Unknown artist of the 18th century.

19 gr. Apraksin Stepan Fedorovich (1702-1758) from 1756

Unknown artist of the 18th century.

20 gr. Saltykov Pyotr Semyonovich (1698-1772) from 1759

Copy of Loktev from the portrait by Rotary. 1762 Russian Museum.

21 gr. Shuvalov Alexander Ivanovich (1710-1771) from 1761

Portrait of Rotary work. Source - Vel. Book Nikolai Mikhailovich "Russian portraits of the 18th-19th centuries"

22 gr. Shuvalov Pyotr Ivanovich (1711-1762) from 1761

Portrait by Rokotov.

23 Ave. Peter August Friedrich of Holstein-Beck (1697-1775) from 1762

Lithograph of Tyulev from unknown. original from the 18th century. Source: Bantysh-Kamensky’s book “Biographies of Russian Generalissimos and Field Marshals”, 1840.

24 ave. Georg Ludwig of Schleswig-Holstein (1719-1763) from 1762

Lithograph of Tyulev from unknown. original from the 18th century. Source - Bantysh-Kamensky's book "Biographies of Russian generalissimos and field marshals" 1840. Follow the link: http://www.royaltyguide.nl/images-families/oldenburg/holsteingottorp/1719%20Georg.jpg - there is another portrait of him of unknown origin and questionable authenticity.

25 grz. Karl Ludwig of Holstein-Beck (1690-1774) from 1762

He was not in Russian service; he received the rank as an honorary title. Unfortunately, despite a long search, it was not possible to find his portrait.

Field Marshals promoted to the rank by Empress Catherine II and Emperor Paul I. Please note that gr. I.G. Chernyshev was promoted to the rank of Field Marshal in 1796 "by fleet".

26 gr. Bestuzhev-Ryumin Alexey Petrovich (1693-1766) from 1762

Copy by G. Serdyukov, from the original by L. Tokke. 1772. State Russian Museum.

27 gr. Razumovsky, Kirill Grigorievich (1728-1803) from 1764

Portrait by L. Tokke. 1758

28 books Golitsyn Alexander Mikhailovich (1718-1783) from 1769

Portrait of work unknown. artist of the late 18th century. State military history Museum of A.V. Suvorov. St. Petersburg

29 gr. Rumyantsev-Zadunaysky Peter Alexandrovich (1725-1796) from 1770

Portrait of work unknown. artist. 1770s State Historical Museum.

30 gr. Chernyshev Zakhar Grigorievich (1722-1784) from 1773

A copy of a portrait by A. Roslen. 1776 State. military history Museum of A.V. Suvorov. St. Petersburg

31 lgr. Ludwig IX of Hesse-Darmstadt (1719-1790) from 1774. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

Portrait of work unknown. artist ser. XVIII century. Museum of History. Strasbourg.

32 St. book Potemkin-Tavrichesky Grigory Alexandrovich (1736-1791) from 1784

Portrait of work unknown. artist. 1780s State Historical Museum.

33 books. Suvorov-Rymniksky Alexander Vasilyevich (1730-1800), from 1794, generalissimo from 1799

Portrait of work unknown. artist (Levitsky type). 1780s State Historical Museum.

34 St. book Saltykov Nikolai Ivanovich (1736-1816) from 1796

Portrait by M. Kvadal. 1807 State Hermitage Museum.

35 books Repnin Nikolai Vasilievich (1734-1801) from 1796

Portrait of work unknown. artist con. XVIII century. State Historical Museum.

36 gr. Chernyshev Ivan Grigorievich (1726-1797), Field Marshal General of the Navy from 1796

Portrait by D. Levitsky. 1790s. Pavlovsk Palace.

37 gr. Saltykov Ivan Petrovich (1730-1805) from 1796

Miniature by A.H. Ritt. end of the 18th century. State Hermitage Museum. St. Petersburg

38 gr. Elmpt Ivan Karpovich (1725-1802) from 1797

Lithograph of Tyulev from unknown. original from the 18th century. Source: Bantysh-Kamensky’s book “Biographies of Russian Generalissimos and Field Marshals”, 1840.

39 gr. Musin-Pushkin Valentin Platonovich (1735-1804) from 1797

Portrait by D. Levitsky. 1790s

40 gr. Kamensky Mikhail Fedotovich (1738-1809) from 1797

Portrait of work unknown. artist con. XVIII century. State military history Museum of A.V. Suvorov. St. Petersburg

41 grc de Broglie Victor Francis (1718-1804), from 1797 Marshal of France from 1759

Portrait of work unknown. fr. artist con. XVIII century. Museum "Invalides" Paris.

Field Marshals promoted to the rank by Emperors Alexander I and Nicholas I.

42 gr. Gudovich Ivan Vasilievich (1741-1820) from 1807

Portrait by Breze. Source book N. Schilder "Emperor Alexander I" vol. 3

43 books Prozorovsky Alexander Alexandrovich (1732-1809) from 1807

Portrait of work unknown. artist of the late 18th - early 19th centuries.

44 St. book Golenishchev-Kutuzov-Smolensky Mikhail Illarionovich (1745-1813) from 1812

Miniature by K. Rosentretter. 1811-1812 State Hermitage Museum. St. Petersburg

45 books Barclay de Tolly Mikhail Bogdanovich (1761-1818) from 1814

Copy unknown artist from the original by Senf, 1816. State Museum. Pushkin. Moscow.

46 grz Wellington Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852) from 1818 British field marshal from 1813. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

Portrait by T. Lawrence. 1814

47 St. book Wittgenstein Peter Christianovich (1768-1843) from 1826

48 books Osten-Sacken Fabian Wilhelmovich (1752-1837) from 1826

Portrait by J. Doe. 1820s Military gallery of the Winter Palace. St. Petersburg

49 gr. Dibich-Zabalkansky Ivan Ivanovich (1785-1831) from 1829

Portrait by J. Doe. 1820s Military gallery of the Winter Palace. St. Petersburg

50 St. book Paskevich-Erivansky-Varshavsky Ivan Fedorovich (1782-1856) from 1829

Miniature of S. Marshalkevich from a portrait of F. Kruger, 1834. State Hermitage Museum. St. Petersburg

51 Erzgrts. Johann of Austria (1782-1859) from 1837 Austrian field marshal from 1836. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

Portrait by L. Kupelweiser. 1840 Schenna Castle. Austria.

52 gr. Radetzky Joseph-Wenzel (1766-1858) since 1849 Austrian field marshal since 1836. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

Portrait by J. Decker. 1850 Military Museum. Vein.

53 St. book Volkonsky Pyotr Mikhailovich (1776-1852) from 1850

Portrait by J. Doe. 1820s Military gallery of the Winter Palace. St. Petersburg

The last 13 people were awarded the rank of field marshal by Emperors Alexander II and Nicholas II (there were no awards under Emperor Alexander III).

54 St. book Vorontsov Mikhail Semyonovich (1782-1856) since 1856

55 books Baryatinsky Alexander Ivanovich (1815-1879) from 1859

56 gr. Berg Fedor Fedorovich (1794-1874) from 1865

57 Archgrtz Albrecht of Austria-Teschen (1817-1895) from 1872, Field Marshal of Austria from 1863. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

58 Ave. Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia (Frederick III, Emperor of Germany) (1831-1888) since 1872, Prussian Field Marshal General since 1870. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

59 gr. von Moltke Helmut Karl Bernhard (1800-1891) from 1872, Field Marshal of Germany from 1871. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

60 Ave. Albert of Saxony (Albert I, Cor. Saxony) (1828-1902) from 1872, Field Marshal of Germany from 1871. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

61 vel. book Nikolai Nikolaevich (1831-1891) since 1878

62 vel. book Mikhail Nikolaevich (1832-1909) since 1878

63 Gurko Joseph Vladimirovich (1828-1901) since 1894

64 gr. Milyutin Dmitry Alekseevich (1816-1912) since 1898

65 Nicholas I, King of Montenegro (1841-1921) from 1910. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

66 Carol I, King of Romania (1839-1914) from 1912. He was not in Russian service, he received the rank as an honorary title.

Sheremetev

Boris Petrovich

Battles and victories

Outstanding Russian commander during the Northern War, diplomat, first Russian field marshal general (1701). In 1706, he was also the first to be elevated to the dignity of a count of the Russian Empire.

In people's memory, Sheremetev remained one of the main heroes of that era. Soldier's songs, where he appears exclusively as a positive character, can serve as evidence.

Many glorious pages from the reign of Emperor Peter the Great (1682-1725) are associated with the name of Sheremetev. The first field marshal general in the history of Russia (1701), count (1706), holder of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, one of the richest landowners, he always, due to his character, remained in a special position with the tsar and his entourage. His views on what was happening often did not coincide with the position of the king and his young associates. He seemed to them a man from the distant past, whom supporters of the modernization of Russia along Western lines fought so fiercely. They, the “thin” ones, did not understand the motivation of this blue-eyed, overweight and leisurely man. However, it was he who was needed by the tsar during the most difficult years of the Great Northern War.

The Sheremetev family was connected with the reigning dynasty by blood ties. Boris Petrovich's family was one of the influential boyar families and even had common ancestors with the reigning Romanov dynasty.

By the standards of the mid-17th century, his closest relatives were very educated people and did not shy away from taking everything positive from them when communicating with foreigners. Boris Petrovich's father, Pyotr Vasilyevich Bolshoi, in 1666-1668, being a Kyiv governor, defended the right to exist of the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. Unlike his contemporaries, the governor shaved his beard, which was terrible nonsense, and wore Polish dress. However, he was not touched because of his military and administrative talents.

Pyotr Vasilyevich, who was born on April 25, 1652, sent his son to study at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. There Boris learned to speak Polish, Latin, gained an understanding of the Greek language and learned a lot of things that were unknown to the vast majority of his compatriots. Already in his early youth, Boris Petrovich became addicted to reading books and by the end of his life he had collected a large and well-systematized library. The boyar understood perfectly well that Russia needed progressive reforms and supported the young Tsar Peter.

However, he began his “sovereign service” in the traditional Moscow style, being promoted to room steward at the age of 13.

The military career of the young nobleman began only during the reign of Fyodor Alekseevich (1676-1682). The Tsar assigned him to be his father’s assistant, who commanded one of the “regiments” in the Russian-Turkish War (1676-1681). In 1679, he already served as a “comrade” (deputy) governor in the “big regiment” of Prince Cherkassy. And just two years later he headed the newly formed Tambov city rank, which, in comparison with the modern structure of the armed forces, can be equated to command of a military district.

In 1682, in connection with the accession to the throne of the new Tsars Peter and Ivan, he was granted the title of boyar. The ruler, Princess Sofya Alekseevna, and her favorite, Prince Vasily Vasilyevich Golitsyn, remembered Boris Petrovich in 1685. The Russian government was conducting difficult negotiations with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on concluding an “Eternal Peace.” This is where a boyar who knew European etiquette and foreign languages was needed. His diplomatic mission was extremely successful. After long negotiations, we managed to conclude “Eternal Peace” with Poland and achieve legal recognition of the fact of Moscow’s conquest of Kyiv 20 years ago. Then, after just a few months, Sheremetev was already the sole head of the embassy sent to Warsaw to ratify the treaty and clarify the details of the anti-Ottoman alliance being created. From there we later had to go to Vienna, which was also preparing to continue the fight against the Turks.

The diplomatic path suited the inclinations and talents of the intelligent but cautious Boris Petrovich better than the military one. However, the willful Fate decided otherwise and led him through life far from the most convenient path. Upon returning from Europe to Moscow, the boyar again had to put on a military uniform, which he did not take off until his death.

In the infantry, the first of the Russians can rightfully be called Field Marshal Sheremetev, from an ancient noble family, tall, with soft features and in all respects similar to a great general.

Swede Ehrenmalm, opponent of Sheremetev

Boris Petrovich commanded the regiments of his Belgorod rank during the unsuccessful second Crimean campaign (1689). His detached position in relation to the events in Moscow in the summer of 1689, when Peter I came to power, played a bad joke on him. The boyar was taken under “suspicion.” Disgrace did not follow, but until 1696 Boris Petrovich would remain on the border with the Crimean Khanate, commanding his “discharge.”

During the first Azov campaign in 1695, Sheremetev led an army operating against Turkish fortresses on the Dnieper. Boris Petrovich turned out to be luckier than the tsar and his associates. In the campaign of 1695, the Russian-Ukrainian army took three fortresses from the Turks (July 30 - Kyzy-Kermen, August 1 - Eski-Tavan, August 3 - Aslan-Kermen). The name of Sheremetev became known throughout Europe. At the same time, Azov was never taken. The help of allies was needed. In the summer of 1696, Azov fell, but this success showed that a further war with the Ottoman Empire was possible only with the combined efforts of all countries participating in the “holy league.”

Trying to please the tsar, Boris Petrovich, of his own free will and at his own expense, went on a trip to Europe. The boyar left Moscow three months after Peter himself left for the West and traveled for more than a year and a half, from July 1697 to February 1699, spending 20,500 rubles on it - a huge amount at that time. The true, so to speak, human cost of such a sacrifice becomes clear from the description given to Sheremetev by the famous Soviet researcher of the 18th century, Nikolai Pavlenko: “... Boris Petrovich was not distinguished by selflessness, but did not dare to steal on the scale that Menshikov allowed himself. If a representative of an ancient aristocratic family stole, it was so moderately that the size of what was stolen did not arouse the envy of others. But Sheremetev knew how to beg. He did not miss an opportunity to remind the king of his “poverty,” and his acquisitions were the fruit of royal grants: he, it seems, did not buy estates...”

Having traveled through Poland, Sheremetev again visited Vienna. Then he headed to Italy, examined Rome, Venice, Sicily, and finally got to Malta (having received audiences during the trip with the Polish king and Saxon Elector Augustus, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold, Pope Innocent XII, Grand Duke of Tuscan Cosimo III) . In La Valletta he was even knighted in the Order of Malta.

No other Russian could boast of such a European “train.” The very next day after his return, at a feast at Lefort’s, dressed in a German dress with the Maltese cross on his chest, Sheremetev boldly introduced himself to the Tsar and was greeted with delight by him.

However, the mercy was short-lived. The suspicious “Herr Peter,” according to the soon published “boyar list,” again ordered Boris Petrovich to go away from Moscow and be “near the city of Arkhangelsk.” They remembered him again only a year later, with the beginning of the Northern War (1700-1721). The war began in August with the march of the main forces of the Russian army to Narva. Boyar Sheremetev was appointed commander of the “local cavalry” (mounted noble militia). In the Narva campaign of 1700, Sheremetev’s detachment acted extremely unsuccessfully.

During the siege, Sheremetev, who was conducting reconnaissance, reported that a large Swedish army was approaching Narva. Russian military leaders, according to Swedish historians, were seized by panic. A captive major of the Swedish army, Livonian Patkul, allegedly told them that an army of 30 to 32 thousand people had approached with Charles XII. The figure seemed quite reliable, and they believed it. The king also believed - and fell into despair. During the battle of Narva on November 19 (30), 1700, the valiant “local cavalry”, without engaging in battle, shamefully fled, carrying Boris Petrovich into the water, who was desperately trying to stop it. More than a thousand people drowned in the river. Sheremetev was saved by a horse, and the royal disgrace was averted by the sad fate of all the other generals, who were in full force captured by the triumphant enemy. Moreover, after a catastrophic failure, the tsar made a temporary compromise with the sentiments of his aristocracy and chose a new commander among the most noble national elite, where Sheremetev at that time was the only person with any knowledge of military affairs. Thus, we can say that, in fact, the war itself at the end of 1700 put him at the head of the main forces of the Russian army.

With the onset of the second war summer, Boris Petrovich began to be called Field Marshal General in the Tsar's letters addressed to him. This event closed a long, sad chapter in Sheremetev’s life and opened a new one, which, as it later turned out, became his “swan song.” The last setbacks occurred in the winter of 1700-1701. Prompted by the tsar’s impatient shouts, Boris Petrovich tried to carefully “test” Estland with a saber (Peter sent the first decree demanding activity just 16 days after the disaster at Narva), in particular, to capture the small fortress of Marienburg, which stood in the middle of an ice-bound lake. But he received a rebuff everywhere and, retreating to Pskov, began to put the troops he had in order.

The combat effectiveness of the Russians was still extremely low, especially in comparison with the albeit small, but European enemy. Sheremetev was well aware of the strength of the Swedes, since he became acquainted with the organization of military affairs in the West during a recent trip. And he conducted the preparation in accordance with his thorough and leisurely character. Even the visits of the tsar himself (in August and October), who was eager to resume hostilities as soon as possible, could not significantly speed up events. Sheremetev, constantly pushed by Peter, began to carry out his devastating campaigns in Livonia and Estonia from Pskov. In these battles, the Russian army hardened itself and accumulated invaluable military experience.

The appearance in Estonia and Livonia in the fall of 1701, 9 months after Narva, of fairly large Russian military formations was perceived with some skepticism by the highest Swedish military command - at least, such a reaction was noted by the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, King Charles XII. Local Livonian military leaders immediately sounded the alarm and tried to convey it to the king, but were unsuccessful. The king made it clear that Livonia had to make do with the forces that he left them. The raids of Sheremetev’s Russian detachments in September 1701 were so far seemingly episodic in nature and, at first glance, did not pose a great threat to the integrity of the kingdom.

The battles near Räpina Manor and Rõuge were only a test of strength for the Russians; a serious threat to the Swedes in this region lurked in the future. The Russians were convinced that “the Swede is not as terrible as he is painted,” and that under certain conditions it would be possible to defeat him. It seems that Peter’s headquarters realized that Charles had given up on Livonia and Ingria and left them to their own fate. It was decided to use these provinces both as a kind of training ground for acquiring combat experience, and as an object for achieving the main strategic goal - access to the Baltic coast. Even if the Swedes figured out this strategic goal, they did not take adequate measures to counter it.

Peter, pleased with the field marshal’s actions in the Baltic states, wrote to Apraksin:Boris Petrovich stayed in Livonia quite happily.

This passivity freed the hands of the Russian army and made it possible to open new theaters of military operations that were inconvenient for the enemy, as well as to seize the strategic initiative in the war. The fighting between the Russians and the Swedes before 1707 was of a strange nature: the opponents seemed to be stepping on each other’s tails, but did not engage in a decisive battle among themselves. At that time, Charles XII with his main forces was chasing Augustus II throughout Poland, and the Russian army, strengthened and on its feet, moved from devastation of the Baltic provinces to their conquest, conquering cities one after another and step by step imperceptibly approaching the achievement of its main goal - access to the Gulf of Finland.

It is in this light that all subsequent battles in this area, including the Battle of Erastfera, should be viewed.

|

|

|

|

In December 1701, cavalry general B. Sheremetev, having waited for reinforcements to arrive and concentrate all the troops into one fist, decided to launch a new surprise attack on the Livonia field army of Major General V.A. von Schlippenbach, located in winter quarters. The calculation was based on the fact that the Swedes would be busy celebrating Christmas. At the end of December, Sheremetev's impressive corps of 18,838 people with 20 guns (1 mortar, 3 howitzers, 16 cannons) set out from Pskov on a campaign. To transport troops across Lake Peypus, Sheremetev used about 2,000 sleds. Sheremetev did not act blindly this time, but had intelligence information about the forces and deployment of Schlippenbach’s units: spies from Dorpat reported this to him in Pskov. According to the information received, the main forces of the Swedes were stationed in this city and its environs.

The commander of the Livonian Field Corps, Major General Schlippenbach, against whom the Russian actions were directed, had approximately 5,000 regular and 3,000 irregular troops scattered across posts and garrisons from Narva to Lake Lubana. Due to Schlippenbach's inexplicable carelessness or lack of management, the Swedes learned too late about the movement of large enemy forces. Only on December 28/29 the movement of Russian troops at Larf Manor was noticed by patrols of a land militia battalion. As in previous operations, the element of tactical surprise for Sheremetev's corps was lost, but on the whole his strategic plan was a success.

Schlippenbach, having finally received reliable news about the Russian movement, was forced to give them a decisive battle. Taking with him 4 infantry battalions, 3 cavalry regiments, 2 dragoon regiments and 6 3-pound guns, he moved towards Sheremetev. So on January 1, 1702, the oncoming battle at Erastfer began, the first hours of which were unsuccessful for Sheremetev’s army. Encounter combat is generally a complex matter, but for the not fully trained Russian soldiers and officers it turned out to be doubly difficult. During the battle, confusion and uncertainty arose, and the Russian column had to retreat.

It is difficult to say how Sheremetev’s operation would have ended if the artillery had not arrived in time. Under the cover of artillery fire, the Russians recovered, again formed a battle formation and resolutely attacked the Swedes. A stubborn four-hour battle ensued. The Swedish commander was going to retreat behind the positions fortified by the palisade at the Erastfer manor, but Sheremetev guessed the enemy’s plan and ordered an attack on the Swedes in the flank. Russian artillery, mounted on sleighs, began to fire buckshot at the Swedes. As soon as the Swedish infantry began to retreat, the Russians overthrew the enemy squadrons with a swift attack. The Swedish cavalry, despite the attempts of some officers to put it in combat formation, fled in panic from the battlefield, overturning its own infantry. The ensuing darkness and fatigue of the troops forced the Russian command to stop the pursuit; only a detachment of Cossacks continued to chase the retreating Swedish troops.

Sheremetev did not risk pursuing the retreating enemy and returned back to Pskov, justifying himself to the tsar by the fatigue of the horses and deep snow. Thus, Russian troops won their first major victory in the Northern War. Of the 3000-3800 Swedes who took part in the battle, 1000-1400 people were killed, 700-900 people. 134 people fled and deserted. were captured. The Russians, in addition, captured 6 cannons. The losses of Sheremetev's troops, according to a number of historians, range from 400 to 1000 people. E. Tarle gives the figure 1000.

This victory brought Sheremetev the title of Field Marshal and the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. The soldiers of his corps received a silver ruble. The significance of the Erastfer victory was difficult to overestimate. The Russian army demonstrated its ability to defeat a formidable enemy in the field, albeit with superior forces.

The Russian army was ready to take decisive action in a new campaign on the territory of Estonia and Livonia only by the beginning of July 1702. With approximately 24,000 dragoons and soldiers, Sheremetev finally crossed the Russian-Swedish border on July 13.

On July 18/19, Sheremetev's corps clashed with the Swedes in the battle of Gummelsgof. The Swedes were the first to start the battle. The Swedish cavalry attacked 3 regiments of Russian dragoons. Swedish artillery provided effective assistance to the cavalry. Russian units began to retreat. At this time, the Swedish cavalrymen, sent to eliminate the supposed flank coverage, themselves went to the rear and flanks of the Russian cavalry and attacked it. The situation for the Russians became critical; the Swedish cavalry captured 6 cannons and almost the entire convoy from us. The situation was saved by the dragoons. They delayed the enemy's onslaught and fought desperately at the bridge over the river. At the most critical moment, 2 more dragoon regiments (about 1,300 people) from Sheremetev’s main forces came to their aid, and this decided the outcome of the battle. Schlippenbach could have defeated the enemy piecemeal, but missed the opportunity to move infantry and cannons to the aid of his cavalry.

Soon military fortunes, it seemed, began to lean again in favor of the Swedes. Two battalions also approached them and entered the battle straight from the march. But they failed to turn the tide of the battle in their favor. Its outcome was decided with the approach of the main forces of the Russian corps to the battlefield.

After effective artillery bombardment, which disrupted the ranks of the Swedish cavalry, the Russian troops launched a general offensive. The Swedish cavalry front collapsed. Its advanced units took a panicked flight, crushed their infantry and rushed to flee along the road to Pernau. Attempts by individual small detachments of infantry and cavalry to hold back the onslaught of Russian troops were broken. Most of the infantry also fled from the battlefield and took refuge in the surrounding forests and swamps.

As a result, the Swedes suffered a heavy defeat. The balance of forces in the battle was 3.6: 1 in favor of the Russians. About 18 people took part in the battle on our side, and about 5 thousand on the Swedes’ side.

O. Sjögren believes that up to 2 thousand Swedish soldiers fell on the battlefield, but this figure seems to be underestimated. Russian contemporary sources estimate enemy losses at 2,400 killed, 1,200 deserters, 315 prisoners, 16 guns and 16 banners. The losses of Russian troops are estimated at 1000-1500 people killed and wounded.

After Hummelshof, Sheremetev became the practical master of the entire southern Livonia, but Peter I considered securing these lands for himself premature - he did not yet want to quarrel with Augustus II. According to the agreement with him, Livonia, after it was recaptured from the Swedes, was to go to Poland.

After Hummelshof, Sheremetev's corps carried out a series of devastating raids on the Baltic cities. Karkus, Helmet, Smilten, Volmar, Wesenberg were devastated. We also went to the city of Marienburg, where commandant Tillo von Tillau surrendered the city to the mercy of Sheremetev. But not all Swedes approved of this idea: when the Russians entered the city, artillery captain Wulf and his comrades blew up a powder magazine, and many Russians died with them under the rubble of buildings. Angered by this, Sheremetev did not release any of the surviving Swedes, and ordered all residents to be taken prisoner.

During the campaign to Marienburg, the Russian army and Russia as a whole were enriched with another unusual acquisition. Colonel R.H. Bauer (Bour) (according to Kostomarov, Colonel Balk) looked for a pretty concubine there for himself - a 16-year-old Latvian, a servant of Pastor Gluck, and took her with him to Pskov. In Pskov, Field Marshal Sheremetev himself had his eye on Marta Skavronskaya, and Marta obediently served him. Then Menshikov saw her, and after him - Tsar Peter himself. The matter ended, as is known, with Marta Skavronskaya becoming the wife of the Tsar and Empress of Russia Catherine I.

After Hummelshof, Boris Petrovich commanded troops during the capture of Noteburg (1702) and Nyenschantz (1703), and in the summer of 1704 he unsuccessfully besieged Dorpat, for which he again fell into disgrace.

In June 1705, Peter arrived in Polotsk and at the military council on the 15th he instructed Sheremetev to lead another campaign in Courland against Levengaupt. The latter was a big thorn in the eyes of the Russians and constantly attracted their attention. Peter’s instructions to Field Marshal Sheremetev said: “Go on this easy campaign (so that there is not a single foot on foot) and search with the help of God over the enemy, namely over General Levenhaupt. The whole strength of this campaign lies in cutting it off from Riga.”

At the beginning of July 1705, the Russian corps (3 infantry, 9 dragoon regiments, a separate dragoon squadron, 2,500 Cossacks and 16 guns) set out on a campaign from Druya. Enemy intelligence worked so poorly that Count Levengaupt had to be content with numerous rumors rather than real data. Initially, the Swedish military leader estimated the enemy forces at 30 thousand people (Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt berättelse. Karolinska krigare berättar. Stockholm. 1987).

The Courland Corps of the Carolinas, stationed near Riga, numbered about 7 thousand infantry and cavalry with 17 guns. In such conditions it was very difficult for the count to act. However, the Russians left him no choice. The king's instructions were unambiguous. Sheremetev was supposed to lock Levengaupt's corps in Courland. The task is more than serious.

In anticipation of the enemy, the count retreated to Gemauerthof, where he took up advantageous positions. The front of the Swedish position was covered by a deep stream, the right flank rested on a swamp, and the left flank on a dense forest. Levenhaupt's corps was significantly superior in quality to Schlippenbach's Livonian field army.

The military council convened on July 15, 1705 by Sheremetev decided to attack the enemy, but not head-on, but using military stratagem, simulating a retreat during the attack in order to lure the enemy out of the camp and hit him from the flank with cavalry hidden in the forest. Due to the uncoordinated and spontaneous actions of the Russian military leaders, the first stage of the battle was lost, and the Russian cavalry began to retreat in disarray. The Swedes pursued her vigorously. However, their previously covered flanks were exposed. At this stage of the battle, the Russians showed steadfastness and bold maneuver. As darkness fell, the battle stopped and Sheremetev retreated.

Charles XII was extremely pleased with the victory of his troops. On August 10, 1705, Count Adam Ludwig Levenhaupt was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general. At the same time, Sheremetev was acutely upset by the failure. It took the consolation of Tsar Peter himself, who noted that military happiness can be changeable. However, this Swedish success changed little in the balance of power in the Baltic states. Soon Russian troops took two strong Courland fortresses, Mitava and Bausk. Levenhaupt's weakened corps at that time sat outside the walls of Riga, not daring to go out into the field. Thus, even defeat brought enormous benefits to Russian weapons. At the same time, Gemauerthof showed that the Russian military leaders still had a lot of work to do - most of all, training the cavalry and developing coherence between the branches of the military.

From this time on, Sheremetev’s career will begin to decline. In 1708, he will be declared one of the culprits in the defeat of the Russian army in the battle of Golovchino. In the victorious Battle of Poltava (1709), Boris Petrovich would be the nominal commander-in-chief. Even after the Poltava triumph, when awards poured in a generous stream on most generals, he had to be content with a very modest salary, more like a formal go-ahead - a run-down village with the downright symbolic name Black Mud.

At the same time, it cannot be said that Peter began to treat the field marshal completely badly. It is enough to recall one example. In 1712, upon reaching his 60th birthday, Boris Petrovich fell into another depression, lost his taste for life and decided to retire from the bustle of the world to a monastery, so that he could spend the rest of his days there in complete peace. He even chose the monastery - the Kiev Pechersk Lavra. Peter, having learned about the dream, became angry, advising his colleague to “get the nonsense out of his head.” And, to make it easier for him to do this, he ordered him to get married immediately. And without delaying the matter, he immediately personally found a bride - the 26-year-old widow of his own uncle Lev Kirillovich Naryshkin.

Some modern researchers, assessing Sheremetev's real achievements from the point of view of European military art, agree with the tsar, giving the field marshal a not very flattering mark. For example, Alexander Zaozersky, the author of the most detailed monograph on the life and work of Boris Petrovich, expressed the following opinion: “...Was he, however, a brilliant commander? His successes on the battlefield hardly allow us to answer this question positively. Of course, under his leadership, Russian troops more than once won victories over the Tatars and the Swedes. But we can name more than one case when a field marshal suffered defeat. In addition, successful battles took place when his forces outweighed those of the enemy; therefore they cannot be a reliable indicator of the degree of his art or talent...”

But in people's memory Sheremetev forever remained one of the main heroes of that era. Soldier's songs, where he appears only as a positive character, can serve as evidence. This fact was probably influenced by the fact that the commander always took care of the needs of ordinary subordinates, thereby distinguishing himself favorably from most other generals.

At the same time, Boris Petrovich got along well with foreigners. Suffice it to remember that one of his best friends was the Scot Jacob Bruce. Therefore, Europeans who left written evidence about Russia during Peter’s time, as a rule, speak well of the boyar and classify him as one of the most prominent royal nobles. For example, the Englishman Whitworth believed that “Sheremetev is the most polite man in the country and the most cultured” (although the same Whitworth did not rate the boyar’s leadership abilities too highly: “... The tsar’s greatest sorrow is the lack of good generals. Field Marshal Sheremetev is a man, undoubtedly possessing personal courage, having successfully completed the expedition entrusted to him against the Tatars, extremely beloved on his estates and by ordinary soldiers, but until now having had no dealings with a regular enemy army..."). The Austrian Korb noted: “He traveled a lot, was therefore more educated than others, dressed in German and wore a Maltese cross on his chest.” Even his enemy, the Swede Ehrenmalm, spoke of Boris Petrovich with great sympathy: “In infantry, the first of the Russians can rightfully be called Field Marshal Sheremetev, from an ancient noble family, tall, with soft facial features and in all respects similar to a great general. He is somewhat fat, with a pale face and blue eyes, wears blond wigs, and both in clothes and in carriages he is the same as any foreign officer...”

But in the second half of the war, when Peter nevertheless put together a strong conglomerate of European and his own young generals, he began to trust the field marshal less and less with command of even small corps in the main theaters of combat. Therefore, all the main events of 1712-1714. - the struggle for northern Germany and the conquest of Finland - did without Sheremetev. And in 1717 he fell ill and was forced to ask for a long-term leave.

From Sheremetev's will:take my sinful body and bury it in the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery or wherever His Majesty’s will takes place.

Boris Petrovich never returned to the army. He was ill for two years and died before he could see the victory. The death of the commander finally finally reconciled the king with him. Nikolai Pavlenko, one of the most thorough researchers of the Petrine era, wrote the following on this occasion: “The new capital lacked its own pantheon. Peter decided to create it. The field marshal's grave was supposed to open the burial of noble people in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. By order of Peter, Sheremetev’s body was taken to St. Petersburg and solemnly buried. The death of Boris Petrovich and his funeral are as symbolic as the whole life of the field marshal. He died in the old capital and was buried in the new one. In his life, the old and the new also intertwined, creating a portrait of a figure in the period of transition from Muscovite Rus' to the Europeanized Russian Empire.”

BESPALOV A.V., Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor

Sources and literature

Bantysh-Kamensky D.N. 3rd General Field Marshal Count Boris Petrovich Sheremetev. Biographies of Russian generalissimos and field marshals. In 4 parts. Reprint of the 1840 edition. Part 1–2. M., 1991

Barsukov A.P. Sheremetev family. Book 1-8. St. Petersburg, 1881-1904

Bespalov A.V. Battles of the Northern War (1700-1721). M., 2005

Bespalov A.V. Battles and sieges of the Great Northern War (1700-1721). M., 2010

Military campaign journal of Field Marshal B.P. Sheremetev. Materials of the military-scientific archive of the General Staff. v. 1. St. Petersburg, 1871

Zaozersky A.I. Field Marshal B.P. Sheremetev. M., 1989

History of the Russian State: Biographies. XVIII century. M., 1996

History of the Northern War 1700-1721. Rep. ed. I.I. Rostunov. M., 1987