Nikolay Bestuzhev. Decembrists brothers Bestuzhev. See what “Bestuzhev, Nikolai Alexandrovich” is in other dictionaries

April 13, 1791 – May 15, 1855

lieutenant captain of the 8th naval crew, Decembrist, naval historiographer, writer, critic, inventor, artist

Family

Father - Alexander Fedoseevich Bestuzhev (October 24, 1761 - March 20, 1810), artillery officer, since 1800 the ruler of the chancellery of the Academy of Arts, writer. Mother - Praskovya Mikhailovna (1775 - 10/27/1846).

On June 15, 1820 he was appointed assistant keeper of the Baltic lighthouses in Kronstadt.

In 1821 -1822 he organized lithography at the Admiralty Department. In the spring of 1822, at the Admiralty Department, he began writing the history of the Russian fleet. On February 7, 1823, he was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, IV degree, for organizing lithography.

In 1824, on the frigate "Provorny" as a historiographer, he made voyages to France and Gibraltar. On December 12, 1824 he was promoted to lieutenant commander. From July 1825 he was director of the Admiralty Museum, for which he received the nickname “Mummy” from friends.

Writer

Since 1818, he was a member of the Free Society for the establishment of schools using the method of mutual education. Member-employee of the Free Society of Lovers of Russian Literature since March 28, 1821, and since May 31, full member. Since 1822, member of the Censorship Committee. Editor. Since 1818, he collaborated with the almanac "Polar Star", the magazines "Son of the Fatherland", "Blagomarnenny", "Competitor of Education and Charity" and others.

Since 1825, member of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists. As a volunteer he attended classes at the Academy of Arts. He studied with A. N. Voronikhin and N. N. Fonlev. Since September 12, 1825, member of the Free Economic Society.

Since 1818, a member of the Masonic lodge “Elect Michael”.

Decembrist

In 1824 he was accepted into the Northern Society by K. F. Ryleev. K.F. Ryleev invited him to become a member of the Supreme Duma of the Northern Society. Author of the project “Manifesto to the Russian People”. The Guards crew led to Senate Square.

Hard labor

On August 7, 1826, together with his brother Mikhail, he was taken to Shlisselburg. Sent to Siberia on September 28, 1827. Arrived at the Chita prison on December 13, 1827. Transferred to the Petrovsky plant in September 1830.

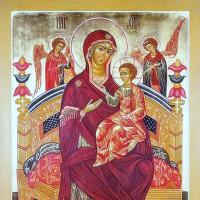

He worked in watercolors and later in oils on canvas. He painted portraits of the Decembrists, their wives and children, city residents (115 portraits), views of Chita and the Petrovsky Factory.

Link

On July 10, 1839, brothers Mikhail and Nikolai Bestuzhev were sent to settle in the city of Selenginsk, Irkutsk province. Arrived in Selenginsk on September 1, 1839.

BESTUZHEV Nikolai Alexandrovich (13.4.1791, St. Petersburg - 15.5.1855, Selenginsk), Decembrist, lieutenant captain, historiographer, writer, critic, inventor, artist. He served in the Admiralty Department, organized lithography with it, and was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th class. Worked on Russian history. fleet. Director of the Admiralty Museum (1825). Member Free Island of Lovers grew up. Literature, Free Island educational institution, Free Economics. Islands, Islands for encouraging artists. Collaborated with the journal. “Polar Star”, “Son of the Fatherland”, etc. Ch. North island, one of the authors of the “Manifesto to the Russian. to the people." Participant in the uprising in St. Petersburg. In Chit. prison delivered 12/13/1827, transferred to Petrovsky Plant on September. 1830. During penal servitude and a settlement in Selenginsk (from 1839) he developed a new chronometer design, improved a gun lock, and was engaged in shoemaking, jewelry, turning and watchmaking. He taught his comrades and local residents how to sew boots and harden steel. Conducted regular meteorological, seismic and astronomical observations, studied the climate features of the Trans-Babush region, affecting the conditions for the growth of agricultural products. crops and hay grasses. I was interested in the rhythms of nature. processes. Supporter of the creation in Russia of a meteorological network operating according to a unified program. He was engaged in gardening, growing tobacco and watermelons. Tried to introduce fine-fleece sheep breeding. He noted the uncontrolled destruction of forests, causing shallowing of swamps and rivers and a decrease in agricultural yields. crops I paid attention to the traces of irrigation systems of the first farmers of the Zab., to the petroglyphs along the river. Selenga. He invented the so-called “Bestuzhev stove” and the crew. Based on the results of nature research in bass. Gusinoe Lake, households and various rituals of the Buryats published an essay “Goose Lake”. Author of a number of other articles on archeology, ethnography, economics and literature. works about the role of the people in history - “Russian in Paris in 1814”, “Notes on the War of 1812”. “Memories of Ryleev” is the best work of the deceased. period published by A. I. Herzen abroad in the 1860s. He worked in watercolors, and later in oils on canvas (portraits of the Decembrists, their wives and children, city residents, views of Chita and the Petrovsky Factory.

Lit.: Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. - M.; L., 1951; Spector M. Memory for descendants // Zab. worker. - 1975. - November 20; Pasetsky V. M. Geogr. research of the Decembrists. - M., 1977; Decembrists: Biogr. reference book / Ed. M. V. Nechkina. - M., 1988; Zilberstein S. I. Decembrist artist Nikolai Bestuzhev. - M., 1988; Tivanenko A. Archaeol. hobbies N. A. Bestuzhev // Sib. and the Decembrists. - Irkutsk, 1988. - No. 5; Konstantinov M. V. Oracles of the ages. Sketches about explorers of Siberia. - Novosibirsk, 2002.

(1791-1855) Russian writer, Decembrist

An outstanding figure in the Russian liberation movement, the Decembrist Nikolai Bestuzhev was a richly and multi-talented person. A sailor and artist, inventor and traveler, naturalist, economist and ethnographer, he also possessed extraordinary literary talent, although his literary fame during his lifetime was eclipsed by the fame of his brother A. A. Bestuzhev-Marlinsky. But the name of Nikolai Aleksandrovich Bestuzhev rightfully belongs to Russian culture and Russian literature. “Nikolai Bestuzhev was a man of genius,” wrote N. I. Lorer, “and, my God, what he didn’t know, what he wasn’t capable of!”

Nikolai Bestuzhev was born in St. Petersburg into a famous noble family. Thanks to his father, he became familiar with literature early and knew music and painting well. At the age of eleven, the boy became a student of the St. Petersburg Naval Cadet Corps. In 1809, after completing his studies, he was left there as a teacher with the rank of midshipman.

During the Patriotic War of 1812, Bestuzhev and his corps were evacuated to Sveaborg, where his affair with L.I. Stepova (the wife of the director of the navigation school in Kronstadt) began. According to one of Bestuzhev’s contemporaries, she had “a strong influence on his life until his civilian death.”

In 1813, Bestuzhev left the corps and began serving in the naval crew stationed in Kronstadt. In May 1815, the ship on which Lieutenant Bestuzhev served went to Rotterdam, and the young officer could observe with his own eyes the establishment of a republic in Holland, which gave him an idea of “civil rights.”

Two years later he set sail again, this time to Calais with his brother Mikhail. Visiting Western countries, getting to know their culture and government structure increasingly strengthened young officers in the idea that the omnipotence of the monarchy was hindering the development of Russia. Thoughts about the future of his homeland soon led Bestuzhev to the Masonic lodge of “Chosen Michael”.

In 1823, he became the head of the Maritime Museum and studied the history of the Russian fleet. By this time, Bestuzhev was already a prominent figure among naval officers and had gained fame in the scientific and literary community. In 1824, K. Ryleev invited Bestuzhev to join a secret society, which was formed by the best representatives of the Russian nobility. Later they would be called Decembrists. They were concerned about the fate of Russia and prepared projects for its transformation. The secret society existed not only in St. Petersburg: its branches were in Moscow, Ukraine, and other places. The St. Petersburg secret society was called Northern, and Bestuzhev was among the most revolutionary-minded group of “northerners.” They insisted on expanding the rights of popular representation and on the release of peasants with land.

Together with his brother Alexander, N. Bestuzhev was one of Ryleev’s main assistants on the eve of the uprising. On December 14, 1825, he brought the Marine Guards crew to Palace Square in St. Petersburg, although for several years he had been with the Admiralty Department and had nothing to do with practical naval service.

Nikolai Bestuzhev also showed courage and perseverance during the investigation into the Decembrist case. He answered questions very restrainedly, admitting only what was known to the Investigative Committee, keeping silent about the affairs of the secret society and almost not naming names. Many memoirists recall how bravely Bestuzhev behaved during interrogations. Thus, I. D. Yakushkin wrote: “In the eyes of the highest authorities, the main guilt of Nikolai Bestuzhev was that he spoke very boldly before the members of the commission and acted very boldly when he was brought to the palace.” During interrogations, he succinctly depicted the difficult state of Russia and already in his first testimony said: “Seeing the breakdown of finances, the decline of trade and the trust of the merchants, the complete insignificance of our methods in agriculture, and most of all the lawlessness of the courts, made our hearts tremble.”

It is also known that after the first interrogation, Nicholas I said about Bestuzhev - “the smartest man among the conspirators.” Six months later, the tsar would award the title of “smartest man” to A.S. Pushkin, but it would cost both “smartest” very dearly: Pushkin would be under secret surveillance, and N. Bestuzhev would be judged especially harshly. The judges' decision was obviously influenced by his behavior during interrogations.

In the “List of persons who, in the case of secret malicious societies, are brought before the Supreme Criminal Court by order of the highest order,” all convicts were divided into eleven categories and one extra-category group. Nikolai Bestuzhev was assigned to category II, although the investigation materials did not provide grounds for such a high “rank”. Obviously, the judges understood the actual role and significance of the elder Bestuzhev in Northern society. “Second-class people” were condemned by the Supreme Criminal Court to political death, that is, “put their heads on the chopping block, and then be sent forever to hard labor.”

Nicholas I introduced a number of “changes and mitigations” to the sentence, moving some “criminals” from one category to another. For those convicted of the second and third categories, eternal hard labor was replaced by twenty years with deprivation of ranks and nobility and subsequent exile to a settlement.

On the occasion of the coronation of Nicholas I, the term of hard labor for the second category was reduced to 15 years. By the Manifesto of 1829, it was again reduced - to 10 years, but Nikolai and Mikhail Bestuzhev were not affected by this reduction, and they settled only in July 1839.

In the casemates of the Petrovsky Factory, N. Bestuzhev again began to actively engage in literary creativity. He wrote romantic stories, travel essays, fables, and poems. His translations from T. More, Byron, W. Scott, Washington Irving appeared in magazines, scientific articles were published - on history, physics, mathematics. Many of his manuscripts were destroyed after the defeat of the uprising, but what was printed is enough to judge the high skill and professionalism in all issues that the author touched upon.

The maritime theme occupies a special place in his work. It is no coincidence that the posthumous collection of selected works by Bestuzhev is called “Stories and Tales of the Old Sailor.” Not only was he himself a sailor and historiographer of the Russian fleet, but his entire family was primarily associated with the sea. Involvement in the fleet undoubtedly contributed to the formation of revolutionary sentiments in the Bestuzhev family.

A new stage in the writer’s creativity began in Siberia. Memories of December 14, as well as a number of artistic works, also brought to life by the tragic events of the uprising, were conceived and partially written here. Both memoir prose and psychological stories, in fact, reveal one theme - the paths that led the participants in the uprising to the square, and then to the “convict holes” - their worldview, their aspirations and hopes.

The memoir prose of Bestuzhev, who, among other things, had a sharp and precise eye as a painter, is especially noteworthy. His widely known “Memoirs of Ryleev” and the short passage “December 14, 1825” were conceived by him as part of more extensive memories of the December events. The plan remained unfinished - we know about this from the memoirs of Mikhail Bestuzhev, Nikolai Alexandrovich himself spoke about this with melancholy before his death.

The image of Ryleev is shown through the prism of a romantic story: he is enthusiastic and sensitive, his eyes “sparkle,” “his face is burning,” and he “cries,” etc., although we know that Ryleev was extremely restrained on the eve of the uprising. “Memories of Ryleev” completes the “biographies of great men” laid down in the program of the Union of Welfare, bringing these biographies up to December 14, 1825.

In his memoir prose, N. Bestuzhev, while maintaining an autobiographical basis, obscures real persons and events with literary details and fiction. In an autobiographical story, the fictional narrative reflects his own experiences. But the work of N. Bestuzhev is not a passive registration of his life conflicts. He creates a generalized image of the Decembrist positive hero. “Shlisselburg Station” can be considered such an autobiographical story. Adjacent to it is the story “The Tavern Staircase.” The fate of the heroes of the work merges with the fate of the author’s political associates. The plot of renunciation of personal happiness serves to express the harsh self-denial of a person who has chosen the path of a professional revolutionary. A man who rebels against autocracy sacrifices his freedom and therefore has no moral right to condemn his beloved woman to suffering, who is expected to be separated from her husband, the father of her children.

Bestuzhev was not the only one who wrote about the problem of personal happiness for a revolutionary. It was put before the members of the secret society by life itself, in which there were many such examples. It is known that some members who started families refused further revolutionary activities.

In the short story “Funeral,” the writer examines the motive of the failed Decembrist. Here the author acts as an exposer of spiritual emptiness and hypocrisy of the “big world”, where decency should replace all feelings of the heart, where everyone looks funny if they show weakness and allow others to notice their inner state. Written in 1829, this story is one of the first prose works in which the falsehood and spiritual emptiness of aristocratic circles are exposed. At this time, the anti-secular stories of V. Odoevsky and A. Bestuzhev had not yet been written. Nor was A. Pushkin’s “Roslavlev” written, where the “secular mob” is shown with the same journalistic fervor as in the stories of N. Bestuzhev.

The story “Russian in Paris 1814” is also connected with reflections on the destinies and characters of the generation that entered life on the eve of the Patriotic War. N. Bestuzhev himself was not in Paris (his military fate turned out differently), and the story is based on the Parisian impressions of his comrades in hard labor, and first of all N. O. Lorer. The moment of Russian troops entering the capital of France, realities, faces, incidents, folk scenes remembered by Laurer - all this was conveyed by Bestuzhev with memoiristic precision. The historian and essayist showed themselves here to the fullest.

“Russian in Paris 1814” is one of the last artistic works of Bestuzhev that has reached us. In Siberia, he wrote a large local history article “Goose Lake” - the first natural science and ethnographic description of Buryatia, its economy and economy, fauna and flora, folk customs and rituals. This essay again reflected the multifaceted talent of Bestuzhev - a fiction writer, ethnographer and economist.

He could not and did not have time to implement many of his plans; some of his artistic works were lost forever during the searches to which the exiled Decembrists were periodically subjected. Nevertheless, his literary heritage is very significant. Bestuzhev can be called one of the founders of the psychological method in Russian literature. An analysis of complex moral conflicts in their connection with a person’s duty to society reveals a genetic connection between his stories and novellas with the works of A. I. Herzen, N. G. Chernyshevsky, L. N. Tolstoy.

N. A. Bestuzhev died in 1855 during the difficult days of the Sevastopol defense for Russia. Mikhail Bestuzhev recalled: “The successes and failures of the Sevastopol siege interested him to the highest degree. During the seventeen long nights of his dying suffering, I myself, exhausted by fatigue, barely understanding what he was telling me almost in delirium, had to use all my strength to reassure him about poor dying Russia. During the intervals of the terrible struggle of his iron, strong nature with death, he asked me: “Tell me, is there anything comforting?”

Until the end of his days, N. A. Bestuzhev remained a citizen and patriot.

Bestuzhev Nikolay Alexandrovich, publicist, writer, artist, born 13(24).IV.1791 in St. Petersburg.

The eldest son of A. F. Bestuzhev (1761-1810) - a writer of a radical movement, one of the publishers of the literary "St. Petersburg Magazine" of the late 18th century.

Nikolai Alexandrovich graduated from the Naval Cadet Corps.

From 1813 he served in the navy, participating in three long-distance voyages; later served as director of the Maritime Museum.

In 1818 Bestuzhev N.A. for the first time began to be published in a magazine. "Well-intentioned." Fluent in English, he translated the works of Byron, Walter Scott, and Thomas Moore. Translations and works of Bestuzhev were published in the magazine of the Free Society of Lovers of Russian Literature “Competitor”. Nikolai Alexandrovich translated mainly those works in which revolutionary-romantic themes predominated.

In 1821, “The Competitor” published Bestuzhev’s first major literary work, “Notes on Holland in 1815” (at the same time it was published as a separate publication). The “Notes” (travel essays) are based on the impressions of the author who visited Rotterdam, Amsterdam, The Hague, Haarlem and Saardam. In his description of Dutch cities, Bestuzhev provided a wealth of material of a natural, historical, political, economic and ethnographic nature. The author expresses his keen sympathy with the struggle of the Netherlands for its independence against Spanish oppression in the 16th century. and speaks favorably of the Dutch Republic. The author reports with obvious dissatisfaction about the subsequent transformation of the Dutch stadtholders into autocrats and their destruction of the republican system. “Notes on Holland” is also accompanied by a historical essay “On the recent history and current state of South America” (“Son of the Fatherland”, part 100, 1825, No. VII, Modern History, 264-279). This article is dedicated to the Paraguayan revolutionary movement led by José Francia.

Great participation Bestuzhev N.A. accepted in the almanac “Polar Star” published by K. F. Ryleev and A. Bestuzhev, which reflected the literary views of the future Decembrists and united everything progressive in Russian literature of those years.

In the prison of the Petrovsky plant, Bestuzhev wrote a treatise, remarkable for that time, “On freedom of trade and industry in general,” which reflected his economic views. In his treatise, Nikolai Alexandrovich closely linked the future economic power of Russia with the destruction of serfdom and the existing system. The treatise gives an idea of the significant evolution that took place in his economic views after December 14, 1825.

The story “Russian in Paris 1814” depicts the image of the Russian officer Glinsky, a participant in the Patriotic War of 1812 and foreign campaigns of 1813-14. An intelligent, noble, well-mannered and educated young man, Glinsky, with all his behavior and attitude towards the defeated French, attracted attention and dissuaded “the prejudice that all French generally had against the Russians.” In the image of Glinsky, the author lovingly emphasized the features of the future Decembrist.

His “Memoirs of Ryleev” are known, in which Nikolai Alexandrovich created a bright, romantic character of an ardent patriot-revolutionary, preserving vitally authentic features and details in the image of Ryleev and in the surrounding environment.

In the story “Shlisselburg Station” Bestuzhev N.A. pursued the idea that in the name of duty, a revolutionary conspirator must completely renounce his personal life and not connect his fate with the fate of the woman he loves. The story is autobiographical. The author emphasized his main idea with an epigraph borrowed from a folk proverb: “One head is poor, and even poor, there is only one.” The story was first published in the collection “Stories and Tales of an Old Sailor” (M., 1860). For censorship reasons, it was renamed: instead of the title “Shlisselburg Station” they put “Why am I not married.”

At the settlement in Selenginsk Bestuzhev N.A. wrote an ethnographic essay “Goose Lake”.

Landscape and portrait painter, Nikolai Aleksandrovich Bestuzhev created an extensive iconography of the first noble Decembrist revolutionaries.

Bestuzhev Nikolai Aleksandrovich died on May 15 (27), 1855 in Selenginsk, Irkutsk province.

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bestuzhev (1791-1855)

Not a single Decembrist family made such a significant contribution to the development of Russian science and culture as the Bestuzhev family. “We were five brothers,” wrote Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bestuzhev in 1869, “And all five died in the whirlpool on December 14” 1. But this was written after decades. And here’s what Fyodor Petrovich Litke, a famous polar explorer, later one of the founders of the Russian Geographical Society and president of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, wrote a few days after the uprising on Senate Square: “The conspirators have already been discovered, and, great God, who do we see between them. Will your heart be overcome, dear Ferdinand, after reading the name of Bestuzhev, this only man, the beauty of the fleet, the pride and hope of his family, the idol, society, my 15-year-old friend? Reading the names of his three brothers, reading the name of Kornilovitch, an anchorite who lived only for sciences?" 2

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. M.; L.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1051, p. 51.)

2 (TsGIAE. F. 2057. Op. 1. D. 452. L. 8. Litke - Wrangel.)

Nikolai, Alexander, Mikhail and Pyotr Bestuzhevs were exiled to hard labor. Later, the same fate befell Pavel, who was not a member of the secret society, but the “Polar Star” was found on his table in the artillery school. And although the book did not belong to him, Paul proudly declared that he was the brother of his brothers. During this year he spent a year in the Bobruisk fortress, and the castle was transferred to a fortress in the Caucasus.

In the vast topic “Decembrists and Russian Culture,” a special place is occupied by the unprecedented activity “for the benefit of the sciences and arts” of Nikolai Aleksandrovich Bestuzhev. He wrote novels and short stories, published “An Experience in the History of the Russian Fleet” and a large number of geographical works. An extensive list of his works, given at the end of the book, opens with an article on electrical phenomena in the atmosphere and ends with the monograph “Goose Lake”. And this is natural, because first of all he considered himself a geographer and physicist, and then a historian, writer, and artist.

N. A. Bestuzhev was born on April 13, 1791. His father, Alexander Fedorovich Bestuzhev, the ruler of the chancellery of the Academy of Arts, “was an educated man, his soul devoted to science, education and service to the Motherland” 1. “Loving science in all its ramifications,” Mikhail Bestuzhev recalled about his father, “he carefully and competently collected a complete, systematically arranged collection of minerals from our vast Rus', semi-precious faceted stones, cameos, rarities in all parts of the arts and arts; acquired paintings metropolitan artists, prints by engravers, models of cannons, fortresses and famous architectural buildings, and without exaggeration one could say that our house was a rich museum in miniature" 2 .

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 205.)

2 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. pp. 206-207.)

Artists, writers, and naturalists visited the Bestuzhevs’ house, including the famous naturalist Academician Nikolai Yakovlevich Ozeretskovsky, who traveled around the White Sea and Lapland, creating a series of works on geographical and physical research of academic expeditions. His major work, “Elementary Foundations of Natural History,” was a major contribution to the Earth sciences.

The Bestuzhev brothers, often present at their father’s conversations with scientists and artists, “unwittingly and unconsciously absorbed at all their pores” 1 their love for science, art, and education. My father's large library contained many geographical works, which especially attracted the attention of children.

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 207.)

Nikolai Bestuzhev was closest to his father. It was the father who developed in his son a love for geography, physics, and mathematics. According to the testimony of the Decembrist’s sister Elena Aleksapdrovna Bestuzheva, A. F. Bestuzhev gave M. V. Lomonosov’s essay “Discourse on the Great Precision of the Sea Route” to read to his eldest son. And soon he and his father visited Kronstadt, where he saw a sea vessel for the first time. “No one,” Nikolai Bestuzhev later wrote, “can imagine the impression made by a huge ship floating on the water, armed with a huge cannon of several floors, equipped with masts that surpass the tallest trees, entangled with many ropes, each of which has a name and purpose, hung with sails, invisible when picked up, and terrible in size when the ship flaps them like wings and flies to fight the winds and waves" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. About pleasures at sea // Polar Star. M.: Goslitizdat, 1960. P. 399.)

At the age of 10, Nikolai Bestuzhev was assigned to the Naval Cadet Corps. He was strongly impressed by the lectures of the honorary member of the Academy of Sciences P. Ya. Gamaleya, the author of multi-volume works that “revived the driest sciences with an eloquent style.” “Having almost been created by him,” Nikolai Bestuzhev said about the scientist’s influence on him, “receiving from him a love of science... when I graduated, I was his last student” 1 . In a letter to his friend M. F. Reinecke, he emphasized that he studied with many teachers, but none of them could compare with Gamaleya in the clarity of presentation “in such dry sciences as navigation, astronomy and the highest theory of maritime art” 2.

1 ()

2 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 511.)

Nikolai Bestuzhev showed such brilliant knowledge of science at the final exams that he was assigned to continue his education at the Paris Polytechnic School. “The beginning of 1810, however, revealed Napoleon’s future intentions, and our departure did not take place,” Nikolai Bestuzhev later wrote 1.

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 511.)

In the Naval Cadet Corps, fate brought him together with the future polar explorer, officer of the Russian fleet Konstantin Petrovich Thorson and the wonderful marine scientist Mikhail Frantsevich Reineke. (True, he met the latter after graduating from the corps, in which he was left as a teacher.) In the summer of 1812, Nikolai received an offer from Lieutenant Commander D.V. Makarov to take part in a voyage to the shores of Russian America. According to Mikhail, he was “ready to set off to distant countries and indulged in rosy dreams, preparing for a trip around the world” 1 . It was probably then that he experienced those feelings that he later described in the article “On the Pleasures of the Sea.”

1 (Education of the Bestuzhevs. P. 290.)

“Will it bring us happiness to find unknown countries?” wrote Nikolai Bestuzhev. “How can we explain the charm of a new, untested feeling at the sight of a special land, at the inspiration of an unknown balsamic air, at the sight of unknown herbs, unusual flowers and fruits, the colors of which are completely unfamiliar to our eyes, taste cannot be expressed in any words or comparisons. How many new truths are revealed, what observations replenish our understanding of man and nature with the discovery of the lands and people of the new world! Isn’t the degree of purpose of the sailor who connects the links of the chain of humanity scattered throughout the world high? !" 1

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. About pleasures at sea. P. 408.)

However, Makarov, who invited Nikolai Bestuzhev to be one of the officers of his ship, quarreled with the directors of the Russian-American Company and was removed from the leadership of the round-the-world expedition. Bestuzhev, who left the Naval Cadet Corps, was approached by the commander of the brig "Rurik" Otto Evstafievich Kotzebue. They met in Kronstadt, and Kotzebue invited Bestuzhev to accompany him on the upcoming voyage, and then sent him a letter in which he repeated his invitation.

“Dear Sir Otto Augustovich!” Bestuzhev answered Lieutenant Kotzebue. “Having received your letter, I hasten to willingly confirm my word to serve with you on the brig “Rurik” and, handing over my fate to you, to congratulate both you and myself on the happy beginning of what was intended. I confess that I was very impatiently awaiting your notification of this and now I am completely beginning to indulge in my joy that I will be able to break out of this inaction, which depresses me, and that by this chance I will be able to become visible on the road to service. One desire remains with me. then to justify the good opinion of my superiors and to pay with my service for the choice from among many of my comrades" 1 .

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 111.)

It is unknown what prevented Bestuzhev from taking part in the upcoming voyage, although he continued to show interest in the problem of the Northeast Passage until the December events of 1825.

In 1815, Bestuzhev made his first voyage to Holland to help Russian troops arrange crossings across large rivers. But the Russian army was already in Paris. Holland made a deep impression on Bestuzhev: “Instead of swampy swamps, instead of cities hanging on stilts above the sea, as I concluded from unclear descriptions of Holland, I saw the sea hanging over the earth, I saw ships floating above houses, lush pastures, clean and beautiful towns , wonderful men and wonderful women" 1.

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Notes about Holland in 1815. St. Petersburg, 1821. pp. 2-3.)

The future Decembrist began studying the history of this country, showing particular interest in the period of republican rule and in the Dutch struggle for independence against Spanish rule. He wrote with admiration about the bourgeois revolution of the 16th century, when “the Dutch showed the world what humanity is capable of and to what extent the spirit of free people can rise” 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Notes about Holland in 1815. St. Petersburg, 1821. P. 16.)

When the Russian sailors left Rotterdam, almost the entire city saw them off. “The Russians tied all the inhabitants to themselves,” noted Bestuzhev. Indeed, having marched from burned Moscow to Paris, they brought the Dutch liberation from Napoleonic tyranny.

1 (Gusev V. E. The contribution of the Decembrists to domestic ethnography // Decembrists and Russian culture. L.: Nauka, 1976. P. 88.)

In 1817, Bestuzhev set sail again, this time to the shores of France. He was accompanied by his brother Mikhail Alexandrovich, who had just graduated from the Naval Cadet Corps. No records about this journey, written by Nikolai Alexandrovich, have survived to our time. M. A. Bestuzhev repeatedly emphasized that the flight from Kronstadt to Calais and back to Russia “poured an abundant stream of beneficial moisture for the growth of the seeds of liberalism” 1 . During his stay in France, the seeds of love of freedom “quickly began to grow and embraced with their roots all the sensations of the soul and heart” 2.

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 239.)

2 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 240.)

In 1818, N. A. Bestuzhev joined the Masonic lodge “Chosen Michael,” which was organizationally associated with the Union of Welfare and to which G. S. Batenkov, F. N. Glinka and F. F. Schubert belonged, who provided considerable services Russian geography. Soon Nikolai Bestuzhev became a member of the Free Society for the establishment of schools using the method of mutual education, which aimed to spread education among the people. Then fate brought him to the Scientific Republic, where he became friends with A. A. Nikolsky, who subsequently did a lot to ensure that the Decembrist’s works about Transbaikalia, written during the years of Selenga exile, saw the light of day. Under the editorship of Nikolsky, 9 of the 13 parts of “Notes published by the Admiralty Department” were published, which consisted mainly of articles of a geographical nature. For many years, Nikolsky sent letters and books to Bestuzhev in Selenginsk from his comrades - F. P. Wrangel, F. P. Litke, M. F. Reinecke, P. F. Anzhu and others.

Soon Bestuzhev was appointed assistant to the director of the lighthouses of the Baltic Sea L.V. Spafariev. The future Decembrist was most attracted to the study of the sea islands of the Gulf of Finland, which, according to him, at that time were mysterious lands even for sailors. He managed to explore only Gotland and some coastal areas of the Gulf of Finland.

Then Bestuzhev was seconded to the Admiralty Department. At the suggestion of Admiral G. A. Sarychev, on March 27, 1822, he was entrusted with “compiling extracts from maritime journals relating to the Russian fleet” 1 . Bestuzhev has long been attracted by the history of navigation. “Before navigation,” he wrote, “even the very thought did not dare to rush further than the pillars of Hercules and each time humbly lay down at their foot; now every new invention, thought, feeling, concept flows around the whole world, is communicated, assimilated and receives the rights of citizenship everywhere "Where only the winds can carry a brave man. Now, through navigation, a wide bridge to beneficent enlightenment has been built everywhere, there are no more obstacles to human communications"19.

1 (TsGAVMF. F. 215. Op. 1. D. 665. L. 4.)

2 (Bestuzhev N.A. About pleasures at sea. pp. 408-409.)

This idea was further developed in the “Experience of the History of the Russian Fleet,” on which Bestuzhev worked hard in 1822-1825. In the Introduction to this work, he considered the beginning of navigation in Rus', the voyages of the ancients to the walls of Constantinople, along the Black and Caspian Seas, campaigns in Pomerania and Pechora. He dwelled in more detail on Russian merchant shipping of the 17th century, which developed only in the Caspian Sea and the White Sea. “This sea,” he wrote about the Caspian Sea, “extends in length from north to south for 1000, and on the longest side for 400 versts and, accepting many rivers, has neither connection with other seas nor other sources and constitutes to this day a mystery for natural scientists, perplexed as to where the water, abundantly brought by the greatest rivers in the world, goes." 1 The issue of fluctuations in the level of the Caspian Sea will continue to attract the attention of the Decembrist.

1 (Memories and stories of an old sailor. M., 1860. P. 181.)

The White Sea is characterized in much more detail. Bestuzhev considered it safe for navigation, “except for the shoal stretching from north to south on the western coast from Cape Svyatogo to Orlov and somewhat south of this latter, to the Ponoya River” 1. This remark was true only in relation to fishing vessels; as for warships, considerable dangers awaited them when sailing the White Sea. During the period of Bestuzhev’s work on the “Experience in the History of the Russian Fleet,” steps were taken to further study the shoals of the White Sea, but these attempts were not very successful. Only in 1827-1832. Bestuzhev's friend, Lieutenant Reineke, managed to complete the sounding of the depths in the White Sea and create an atlas, which served as a reliable navigation aid for a whole century.

1 (Memories and stories of an old sailor. M., 1860. P. 182.)

Having briefly described the port cities of Kola and Arkhangelsk, characterizing the state of trade in the north in the 15th century, he noted that the northern seas have long been known to Russians and that English travelers who were looking for the Northern Sea Route to India, back in the middle of the 16th century. met dozens of Pomeranian ships. Nikolai Bestuzhev dwelt in detail on the great Russian geographical discoveries in Siberia and the north. Having talked about the voyage of Fedot Alekseev and Semyon Dezhnev from Kolyma around the Chukotka Peninsula to the Pacific Ocean, he supported the point of view of Academician G. Miller that “neither before nor after Dezhnev was any of the travelers so happy as to circumnavigate the Northern Ocean near the Chukchi nose in Eastern Ocean" 1. According to the Decembrist, “the reason for the success of his journey was accidental or the warmth of the summer moved the ice away from the shores, which has since forever blocked the passage separating Asia from America” 2 .

1 ()

2 (Memories and stories of an old sailor. M., 186. P. 186.)

Perhaps the origins of Bestuzhev’s such judgments lay in the study of Russian maps, where a straight line was often drawn beyond Cape Shelagsky to the north with the inscription: “Eternal Ice.” But, what is more likely, the messages of the leader of the expedition to the North Pole, M. N. Vasiliev, played a role here. His ships in the summer of 1820 and 1821 to the west and northeast of the Bering Strait they encountered impassable ice and were unable to break through either towards the Kolyma River or towards the Atlantic Ocean, although they penetrated further north than J. Cook managed. Bestuzhev assessed Dezhnev’s voyage as an outstanding geographical discovery, thanks to which the Russians became aware of the Arctic Sea in the northern part of the Eastern (Pacific) Ocean. The Decembrist was convinced that the name of this sailor “will remain unforgettable in the chronicle of discoveries” 1 . Next, Bestuzhev talked about the travels of Mikhail Stadukhin, Vasily Poyarkov and voyages in the Arctic Sea and the Eastern Ocean.

1 (Memories and stories of an old sailor. M., 186. P. 186.)

Of interest is the section on Russian forests stretching from the Baltic to the Pacific Ocean. Bestuzhev described the boundaries of their distribution to the north and south, assessed their suitability for shipbuilding and noted their gradual disappearance. “Three hundred years before this, Russia was covered with forests, especially its northern part; the remains of destroyed forests in the middle and south serve as evidence that these parts were also forested. But the cattle breeding of the southern peoples, who destroyed the forests for convenient pastures, and the agriculture of the inhabitants of the central part of Russia , who until the time of Peter I considered it useful to cut out and burn out groves for arable land and hayfields, left us only sad monuments of vast forests in naked valleys, where the lack of this beneficial work of nature is very sensitive" 1 .

1 (Memories and stories of an old sailor. M., 186. P. 191.)

Subsequently, in exile, Bestuzhev will study in more detail the issue of the influence of forests on climate. But this observation made in passing is also very important. It testifies to the extraordinary breadth of Bestuzhev’s scientific interests in the field of geography. On July 28, 1822, Bestuzhev read the introduction to “Notes on the Russian Fleet” at a meeting of the Admiralty Department. The Department recommended publishing it “in some periodical” 1 . In 1823-1825 New chapters of N. A. Bestuzhev’s “Historical Notes”, dedicated to the activities of the fleet at the beginning of the 18th century, were heard and approved. 2

1 (TsGAVMF. F. 215. Op. 1. D. 655. L. 12.)

2 (TsGAVMF. F. 215. Op. 1. D. 655. L. 16.)

In the summer of 1824, Bestuzhev took part in a voyage on the frigate "Provorny", where he acted as a historian, watch officer and diplomat. Excerpts from the Decembrist's travel journal were published in the eighth part of "Notes published by the Admiralty Department" in 1825. In the same year, "The Voyage of the frigate "Provorny"" was published as a separate book with three maps attached.

This work of the Decembrist contains many records about the state of the weather and the sea, notes related to nautical sciences, including geography, information about lighthouses along the entire sailing route from Kronstadt to Gibraltar and back to Kronstadt, about the structure of ports, about the maritime telegraph, maritime history museums, botanical gardens and various attractions. Bestuzhev's range of interests is extremely wide. In Copenhagen, he first of all visits the observatory, then meets with the director of the Hydrographic Depot and Danish lighthouses, Rear Admiral Leverner. This “76-year-old man with the vivacity of a 19-year-old youth” delights the Decembrist with his scholarship, and above all, with his extensive information on cartography. His collection of maps and books on the geography of the sea amazes Bestuzhev with its amazing selection, especially its “strict accuracy and fidelity” 1 .

1 ()

The frigate "Agile" was caught by a fresh wind while sailing in Kattegat. An ensuing squall tore one of the sails (the mainsail), which was hastily untied and replaced with a new one. For six days a storm tossed the ship in the straits. Only on July 3, 1824 “we finally got out into the German Sea.” The situation was aggravated by the fact that during this time there was foggy weather, which “did not allow us to take a single observation” 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Extract from the journal of the navigation of the frigate "Provorny" in 1824 // Zap. Admiralt. dept. 1825. Part 8. P. 32.)

The Decembrist briefly spoke about his stay in the French port of Brest. “This raid,” he wrote, “is closed in a circle, like Sveaborg; the view of the city, built as an amphitheater, is magnificent and is extremely decorated with the ancient castle, which served as the palace of the glorious Anne of Brittany. One tower, they say, dates back in its construction to the time of Julius Caesar. Now it is painted with white paint so that the telegraph standing in front of it would be more visible, and barracks were made from the apartments of Anne of Brittany" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Extract from the journal of the navigation of the frigate "Provorny" in 1824 // Zap. Admiralt. dept. 1825. Part 8. P. 36.)

With deep warmth, Bestuzhev wrote about the coastal inhabitants of Brittany, calling them “the best sailors.” Living on the rocky shores of a stormy sea with its dangerous underwater and surface rocks and in dangerous proximity to even “more dangerous neighbors,” the Bretons, according to the Decembrist, acquired amazing abilities for courageous voyages on their ships, on which they were in plain sight during the last war The British bravely made their way between the coastal rocks and shoals. "The Bretons are sincere, good-natured, hospitable and have all the good qualities characteristic of northern peoples" 1. These remarks about the differences in the ethnic type of Bretons are highly appreciated by Soviet ethnographers 2.

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Extract from the journal of the navigation of the frigate "Provorny" in 1824 // Zap. Admiralt. dept. 1825. Part 8. P. 77.)

2 (Gusev V. E. Contribution of the Decembrists... P. 88.)

Nikolai Bestuzhev dwells in more detail on the description of the Atlantic coast of France and the climatic features of Brittany. “All of Normandy, Brittany and other provinces right up to Spain are surrounded by rocks and underwater rocks,” noted the Decembrist. “The shores surrounding these provinces consist of high calcareous, chalk or granite cliffs. The soil inside the earth is very fertile. Brittany in particular is extremely famous large strawberries exported from Hili. The climate of Brittany is bad, rainy and foggy, only the rain and sun often change. The reason for this is the position of the province along the [English] Channel, where all the fogs and rains coming from the Atlantic Ocean into our seas are collected" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Extract from the journal... P. 75-76.)

Bestuzhev mapped the shores in the vicinity of Brest, its roadstead and exits from the canal and the Atlantic Ocean. This map was published in 1825 and is published in our study as one of the evidence of the Decembrist’s tireless work in the field of geography.

No less interesting are Bestuzhev’s hydrographic notes about Gibraltar, the entrance to which was opened to sailors on August 5, 1824. Before entering the strait, the sailors descended to the shores of Africa to Cape Spartel and the city of Tangier. “The African mountains are wild and harsh,” wrote Nikolai Bestuzhev, “the thick atmosphere crushes them, encircles them with clouds and covers them in the distance with some kind of purple stripe” 1. The shores of Africa adjacent to Gibraltar were plotted by the Decembrist on a map that is highly accurate. According to him, entering the strait, which has a width of 14 to 20 versts, is not difficult for sailing ships, since the considerable depths allow one to approach its shores within a short distance 2. It is preferable for ships to stay on the African coast, because the opposite, European coast, starting from Cape Trafalgar to the city of Tarifa, has very dangerous pitfalls and banks. In the middle of the Strait of Gibraltar, connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean, according to the Decembrist, there was always a strong current directed from west to east. In his opinion, it was caused by the ebb and flow of the Atlantic Ocean, which is directed in the strait towards the Mediterranean Sea.

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Extract from the magazine... P. 93.)

2 (Bestuzhev N. A. Extract from the journal... P. 87-88.)

“In replacement of this current,” continued Bestuzhev, “near both banks there are two on each side, so that one always goes with the tide, the other back and at low tide the same way. The features separating these currents from the middle one and each one from each other are very noticeable on the surface of the water. Regardless of the average current, there is another one at some depth from the water horizon, the direction of which always goes to the west. The tide goes into the Mediterranean Sea as far as Malaga, where it becomes completely invisible" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Extract from the magazine... P. 84.)

Bestuzhev described the climate of Gibraltar as unbearably hot with cold nights and heavy dew. Summer lasted about 10 months. Sometimes during this period not a single rain fell, and then everything dried up and burned. The best time of the year here is winter: the days became cooler, the drought was replaced by intermittent rains, the plants and trees came to life, the earth was covered with greenery, the air became fresh and life-giving, and the reservoirs were filled with water (most of the year water is delivered by donkeys from Spain). At the same time, Bestuzhev noted that the climate in Gibraltar is generally healthy. The only exceptions are periods when eastern winds blow and “bring with them hot, suffocating and damp weather, which, while relaxing a person, causes colds, headaches and other attacks.” “They say,” the Decembrist continued, “that in this wind one should not store anything for future use, pour wine, salt meat, etc., otherwise everything will soon be spoiled” 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Extract from the magazine... P. 101.)

The essay about Gibraltar is interesting not only from a scientific point of view. Many of its pages are devoted to the exploits of the “constitutional Spaniards” in their unequal battle with French troops. These social motives are strengthened, aggravated and sound like a call to fight for freedom. The section of the book about the stay of the frigate "Agile" in Gibraltar was published by Nikolai Bestuzhev in the famous "Polar Star", which was published by his brother Alexander together with Ryleev 1. After a four-day rest in Gibraltar, the frigate "Agile" again entered the Atlantic Ocean. On August 6, the sailors were already in Plymouth. Here they were kept in quarantine for five days, but even then the British authorities did not allow the sailors to go ashore. “Without the right to leave the frigate,” wrote Nikolai Bestuzhev, “one cannot say anything about Plymouth.” The Decembrist was forced to limit himself to only photographing the Plymouth roadstead, the map of which he published in 1825.

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Gibraaltar // Polar Star. St. Petersburg, 1825. P. 614.)

Throughout the entire voyage, an atmosphere of frank exchange of thoughts about the current state and future of the Fatherland was established on the ship. Many officers shared Bestuzhev's freedom-loving beliefs. It is no coincidence that more than half of the team was involved in the investigation into the uprising on Senate Square, including Epaphroditus Musin-Pushkin, Vasily Speyer, Mikhail Bodisko, Alexander Belyaev, Pyotr Miller, Dmitry Lermantov.

Returning to St. Petersburg, Bestuzhev actively became involved in the activities of the Northern Society. At the same time, the Decembrist was also successfully involved in the affairs of the naval service. His travel notes about sailing on the frigate "Provorny" were warmly received in St. Petersburg.

As can be seen from the correspondence of F. F. Bellingshausen with the Chief of the Naval Staff, in January 1825, Admiral Sarychev proposed to the Admiralty Department to elect Nikolai Bestuzhev as an honorary member. “His excellent talents, knowledge of science and literature, as well as useful works on the naval unit are known to all members of the department and make him, in all fairness, deserving of the honor of belonging to our class,” wrote Sarychev. Such a sign of our attention to this worthy officer will worsen his jealousy for further success in the field of service and studies of scientists" 1.

1 (TsGAVMF. F. 166. Op. 1. D. 2410. L. 1.)

The Admiralty Department “accepted this proposal with pleasure,” and F. F. Bellingshausen on January 27, 1825 asked the Chief of the Naval Staff A. V. Moller to agree to Bestuzhev’s nomination as an honorary member. Three days later, consent was received.

On January 30, 1825, Bestuzhev was unanimously elected a member of the state Admiralty Department - a collegial institution of the naval department - which was in charge of the scientific activities of the fleet, including the preparation and equipment of expeditions, hydrographic work on the seas, was in charge of educational institutions, museums, libraries, observatories, and published maps and essays on the maritime sector. In the "Notes" of this department, part of the works of the Decembrist was first seen.

So Bestuzhev became a member of an institution that did a lot for the development of Russian geography. Its members at that time were Sarychev, Golovnin, Kruzenshtern, Bellingshausen, Rikord, Litke.

The unanimous election of Bestuzhev as an honorary member of the Admiralty Department was recognition of his merits as a geographer, historian, hydrographer and writer. Contemporaries called him “a constellation of talents,” “the beauty and pride of the fleet.” According to his sister Elena Alexandrovna, half of St. Petersburg loved him. In seven years, from 1818 to 1825, he published over 25 works in various fields of science and art (many manuscripts were destroyed after the defeat of the uprising on Senate Square 1).

1 (Literary heritage. L.; M.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1956. T. 60, book. 2. P. 67.)

In mid-1825, Bestuzhev was appointed director of the museum at the Admiralty Department. “Here,” Mikhail Bestuzhev wrote about his brother, “a vast field opened up for his mental and technical activity” 1 . The museum's archives and models were in a chaotic state. He had no choice but to put in order the documents piled up in a heap, covered with dust.

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 52.)

According to M. Yu. Baranovskaya, Nikolai Bestuzhev “replenished the types of lands newly discovered and developed by Russian sailors, systematized the unique objects taken out from there into groups and compiled a museum index with a brief but clear description of the lands and exhibits concentrated in the museum” 1.

1 (Baranovskaya M. Yu. Decembrist Nikolai Bestuzhev. M.: Goskultprosvetizdat, 1954. P. 41.)

Along with historical research, one of the first places in Bestuzhev’s scientific interests belonged to the geography and physics of the Earth. From the time of his voyage to Holland, he was fascinated by meteorology, especially electrical phenomena in the atmosphere. But these problems really began to occupy the Decembrist during the years of exile. Let us recall that Bestuzhev, being a consistent supporter of republican rule in Russia, took part in the development of the plan for the uprising on December 14, 1825. 1 On this great day, Bestuzhev showed courage and bravery by leading the guards to Senate Square.

According to him, he did everything to be shot. The Supreme Court sentenced Bestuzhev to “political death,” in other words, to “placing his head on the block,” and then to exile to hard labor. The same punishment, provided for “state criminals of the second category,” was also imposed on his brother, Mikhail Alexandrovich. On July 11, 1826, Nicholas I showed the “highest mercy” for the “out of grade” - Pestel, Ryleev, Kakhovsky, Sergei Muravyov-Apostol, Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin - wheeling was replaced by the gallows, and the death penalty for those convicted in the first category was replaced by eternal hard labor. Eternal hard labor for second-class prisoners was limited to 20 years. Only in relation to the Bestuzhevs was the verdict of the Supreme Court upheld by Nicholas I. They were sentenced to hard labor forever.

On July 13, 1826, at the Kronstadt roadstead, on board the ship "Prince Vladimir" with N.A. Bestuzhev, the officer's uniform was torn off, the sword was broken over his head and thrown into the sea along with his clothes. For more than a year, the Bestuzhevs were kept first in the Peter and Paul Fortress and then in the Shlisselburg Fortress. At the end of September 1827 they were sent to Chita, where they were “placed” on December 13, 1827.

In the Chita prison, N. A. Bestuzhev’s activities began to create an art portrait gallery of his fellow prisoners. He takes part in classes at the “casemate academy”, giving lectures on the history of the Russian fleet. The Decembrists (Laurer, Rosen, Basargin) call Bestuzhev a man of genius, an unusually gifted inventor, a master with golden hands. The high authority and unusually wide range of interests of Nikolai Bestuzhev in literature and art, politics and mechanics, natural science and history could not but influence the activities of the Decembrists in Chita and especially in the Petrovsky Plant, where news of not only politics, but also science was discussed. The Decembrists called both Chita and the Petrovsky plant a wonderful school and the basis of their “mental and spiritual education” (Obolensky, Belyaev) 1 .

1 (Baranovskaya M. Yu. Decembrist Nikolai Bestuzhev. pp. 106-107.)

At first, according to M. A. Bestuzhev, in the Chita prison “there was nothing to read except the Moscow Telegraph and the Russian Invalid, which were given by the commandant in great secrecy.” But gradually, through their relatives and wives who followed their husbands to Siberia, the prisoners received all the publications of interest that were published in Russia and abroad.

The Petrovsky plant compiled an extensive library, which contained about “half a million books” (Zavalishin) and “a large number of geographical maps and atlases” (Yakushkin). According to Nikolai “Bestuzhev, during the years of imprisonment he did not lack spiritual food. “Having lived in the dungeon, in society,” he wrote to his friend I. I. Sviyazev in 1851, “we formed little by little, but wrote out a lot, a lot magazines, and among them there are many scientists, both Russian and foreign, among other things, and Academic Notes." 1 Bestuzhev later admitted that in all magazines and newspapers he first of all looked for "news on the sciences" and devoted all his "time to the sciences , experiments, observations" 2.

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 4. L. 32. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

2 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 4. L. 92. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

Of course, science occupied the main place in the life of the Decembrist during the years of hard labor. “The field of science is not forbidden to anyone,” he wrote to brother Paul, “everything can be taken away from me except what has been acquired by science, and my first and liveliest pleasure was to always follow science” 1 .

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 9. L. 100.)

While still in Chita, N.A. Bestuzhev began working on a simpler, more accurate and cheaper chronometer, so necessary for determining the location of a ship at sea. At the Petrovsky plant, in the casemates of which at first there were no windows, and then “they gave light for a penny,” he continued to make watches during daylight hours. In the evenings, in the dim light of a candle, according to M. A. Bestuzhev, his brother read new books and magazines, and at night he wrote articles about freedom of trade and industry, about the temperature of the globe 1. The study of the climatic features of first Chita, and then the Petrovsky plant was the most accessible area of scientific study for prisoners.

1 (Memoirs of the Bestuzhevs. P. 322.)

The letters of N.A. Bestuzhev, sent to him from the casemate, contain notes of a meteorological nature. “Our autumn was also long,” the Decembrist reported on January 29, 1837 from the Petropavlovsk plant to brother Pavel, who was complaining about the length of the St. Petersburg autumn, “although in general the local meteorology is completely opposite to yours: when it’s warm here, we have severe frosts; and if during Throughout Europe, winters are cold; here on the peaks of the Himalayas everyone is surprised that the cold does not rise above 30 0 "1.

1 ()

From the further text of this letter it becomes obvious that the Decembrists had not only thermometers, but also barometers for meteorological observations. “Don’t be surprised,” continued N.A. Bestuzhev, “that we consider ourselves inhabitants of the Himalayas: the Tibetan range with its Himalayas, Davalashri and other still highest mountains is the father of our Yablonny, Stanovy and other ranges, and if we do not live on the highest point of the Asian continent, at least close to it. According to our approximate calculations, according to incorrect barometers that arrived from Russia damaged, our height above the sea is about 1 1/2 versts; judge in what rarefied air we exist, despite this that they are surrounded by swamps, or, better to say, physically they further increase the rarefaction of the air" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Articles and letters. M.; L.: Publishing House of Political Prisoners, 1933. P. 256.)

The Decembrist's correspondence contains many original thoughts about the influence of terrain on climate and electrical phenomena in the atmosphere. “Electricity,” the Decembrist wrote to brother Pavel on January 29, 1837, “is so strong here that in winter you can’t touch anything without a spark jumping out; your fur coat shines when you take it off; your hair throws sparks and stands on end if you scratch it.” with their comb; the door, painted with oil paint, glows if you quickly pass your hand over it, and this tense state of the atmosphere is harmful to everyone who has weak nerves. Not only all our ladies (wives - V.P.) suffer, but even many local the natives complain of constant nerve disorder. Moreover, the soil, almost composed of iron ores, constitutes for us a kind of “Leyden jar” in which we live" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Articles and letters. M.; L.: Publishing House of Political Prisoners, 1933. P. 256.)

This is the first observation in the history of meteorological observations about the peculiarities of the electrical state of the atmosphere in Transbaikalia, which coincide in general terms with the rates observed in our time at inland Antarctic stations. It is also interesting because the Decembrist extremely accurately noticed the impact that climatic conditions have on human health.

It is symbolic that the very first known scientific article of the Decembrist relates to the field of meteorology. Under the title “On Electricity in Relation to Certain Air Phenomena,” it was published in 1818 in the journal “Son of the Fatherland.” According to P. A. Bestuzhev, scientists are unanimous that electricity is involved in atmospheric phenomena. However, existing opinions and theories are very contradictory and cannot be considered satisfactory.

Based on his observations of electrical phenomena in the atmosphere over several years, the Decembrist attempted to explain the role of electricity in meteorological phenomena. He believed that above the earth's surface there is an "electric atmosphere that exists around any electrified body." The state of this "electric atmosphere" influences the formation of clouds and fog. At the same time, Bestuzhev noted that the sun takes a “great part” in the excitation of atmospheric electricity, and, in particular, he explained the fall of dew as “a fall of vapor with weakening electricity.”

Conducting experiments using the machine he designed, Bestuzhev came to the conclusion that “earthly electricity is excited by any air changes.” This phenomenon can be influenced by various reasons: “For example, air moving with moderate winds can produce electricity of one kind, but when heated by the sun’s heat it becomes a conductor and then produces another kind of electricity in the ground; low and swampy places are electrified differently from dry and sandy ones.” , and so on" 1.

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. About electricity in relation to some air phenomena // Son of the Fatherland. 1818, Part 49. P. 314.)

Nikolai Bestuzhev believed that the main reason for atmospheric changes lies in changes in the amount of electricity and in the ratios of electrical charges; from this position he explained such meteorological phenomena as rain, snow, hail, fog, thunder, lightning. His views were influenced by the desire of his physicist contemporaries to see electricity as a universal phenomenon that determines the physical processes occurring on Earth.

It should be emphasized that Bestuzhev did not look at the theory he proposed as the ultimate truth. “Not being a deep scientist myself,” he wrote, “I can easily be mistaken in my opinions; but with all that, I invite the gentlemen who test nature to repeat my experiments and test them with their own, which, if they prove the justice and errors in what I propose, then at least At least they will lead to further discoveries in this area and will improve what still awaits improvement" 1.

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. About electricity in relation to some air phenomena // Son of the Fatherland. 1818, Part 50, pp. 33-34.)

During the years of hard labor, the Decembrist very closely followed the progress in the study of atmospheric electricity. This can be seen from his letter to his brother Pavel, sent from the Petrovsky plant in January 1837: “We now read from time to time various theories of scientists, derived from meteorological experiments about the northern lights, about hail, thunderstorms, rain, etc., and I, the poor man, back in 1818 in "Son of the Fatherland", it seems in November or December, published an article "On electricity in relation to air phenomena", where my theory, stated in a list-like manner and with the timidity of first experience, surprisingly how it meets your requirements I could not prove it then and did not dare to do so, but I had a presentiment that magnetism, electricity, galvanism and even the attractive force are nothing more than phenomena of one and the same force. I said this when finishing the article - and that Now all this has been proven: they even think that attractive force is the mother of all “phenomena...” 1

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Letter writing. P. 257.)

Over the course of many years, Bestuzhev returned again and again to the provisions of his first meteorological work and noted that all his conclusions were confirmed by modern research and the assumptions made over 30 years were justified. “I said back then,” Bestuzhev wrote to Professor I. I. Sviyazev of the Mining Institute, “that electricity, galvanism, chemistry, magnetism are developments of the same attractive force. Now, when there are so many scientists in all parts of the world who have never heard of about my article, they wrote in various passages, articles, essays about the results of their experiments, now no one doubts that all these forces are the same" 1 .

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 4. L. 169. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

Next, Bestuzhev recalled that in the same article he described the nature of the northern lights, which “modern physicists” are now busy trying to explain. Indeed, in an article on the significance of electrical phenomena in atmospheric processes, the Decembrist defined “auroras as a silent outpouring of abundant electricity,” which corresponds to modern scientific ideas.

Auroras, like electrical phenomena in the atmosphere, remained at the center of the natural science interests of the Decembrist in Siberia. It is known that Bestuzhev considered it necessary to organize systematic observations of the auroras and asked Reinecke for assistance in this matter. The marine scientist, who provided important services to Russian meteorology by creating many stations and observatories on the seas of Russia, subsequently included Bestuzhev’s proposals in instructions for observations in seaports.

While settling in Selengipsk, Bestuzhev tried to begin studying the relationship between various atmospheric phenomena. This is evidenced by the following excerpt from an unpublished letter from the Decembrist dated August 2, 1851 to Sviyazev: “Nature is very simple in its laws, and it seems that this law is one, but it can only manifest itself in movement. This is a little bold and dark, and Until I express myself somehow more clearly, I will turn again to electricity simply. My observations on the barometer and thermometer, although bad, although often interrupted by absences for housework, for example, I am now going to mow 15 miles away and will stay for at least 2 weeks and etc., but still these observations lead me to some conclusions. Not long ago two weeks ago the barometer dropped to 26d and we had a terrible torrential rain, which did a lot of damage."

1 (IRLI. F. 265. Op. 2. D. 235. L. 10. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

Streams of water, carrying stones, sand and trees, rolled into Selepga in waves. Then the pressure dropped another inch, the clouds descended halfway up the surrounding mountains and swirled wildly. The next morning there was an extraordinary downpour that drenched the area within half an hour. Although the rain stopped, the pressure continued to drop and by midnight reached 25 inches and only then began to rise. Judging by this letter, Bestuzhev was interested in studying the relationship of electrical phenomena in the atmosphere with temperature, pressure and humidity. He regretted that he did not have and could not make instruments for observing atmospheric electricity. In the same letter, which is largely devoted to the Decembrist’s meteorological observations, he repeatedly returned to the idea of the need for a systematic study of atmospheric electricity.

“...In all the meteorological observations that I managed to see published,” he wrote to Sviyazev, “there is everything: the degree of air density according to the barometer, and its thermometric state, and the degree of vapor elasticity, and the declination and inclination of the magnetic needle, and the main “In my opinion, the causes of all these phenomena - electricity - are not observed at all" 1.

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 23. L. 54-55. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

In another letter to Sviyazev, Bestuzhev noted that he read with great satisfaction in the Petersburg Gazette about the negotiations between the director of the Main Physical Observatory, Academician A. Ya. Kupfer, and Western European meteorologists on the unity of observations. At the same time, he was deeply upset by the fact that observations of atmospheric electricity had not yet become the subject of systematic and thorough study and that this important phenomenon was recorded only by a few private observatories, and not by state geophysical networks 1 .

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 23. L. 59. Bestuzhev - Sviyazev.)

Having settled in Selenginsk in 1839, Bestuzhev continued to study the peculiarities of the climate of Transbaikalia. He began to conduct meteorological observations. And although the journal with his notes apparently did not survive, interesting information about the climate of Selenginsk, which he reported in letters to his relatives, has reached us.

September 13, 1838“The climate here is healthy and excellent in comparison with our Petrovsky and your St. Petersburg. Clean mountain air, purified by a fast river, the absence of swamps and sandy soil, which is unpleasant in other respects (sand storms - V.P.), eliminate diseases. We are up to "We still eat melons and watermelons grown in the open air. Our days are hot to this day; the nights were the same, if the coolness of the river without any dampness did not moderate them. Do not think, however, from this description that I I want to imagine Selenginsk as an earthly paradise..." 1

1 (Bestuzhevs Mikhail and Nikolai: Letters from Siberia. Irkutsk: Vosg.-Sib. book publishing house, 1933. pp. 9-10.)

October 25, 1839“Autumn is amazing here. November is already upon us, and I haven’t yet hidden my nose in a warm fur coat; the lack of snow deceives the feeling of cold even more. Already about two weeks ago, slush (in your name) is blowing along the river, and it "In the mid-day thaw, I don't even think about it. Some channels froze, distant banks appeared, and yet I skated and admired through the crystal-like surface of the ice how myriads of colorful fish played in the sun under my feet."

1 (Bestuzhevs Mikhail and Nikolai: Letters from Siberia. Irkutsk: Vosg.-Sib. book publishing house, 1933. P. 17.)

November 15, 1839“Autumn... was unusually good here; and now the days are very good, although the cold sometimes reaches 25° or more” 1.

1 (Bestuzhevs Mikhail and Nikolai: Letters from Siberia. Irkutsk: Vosg.-Sib. book publishing house, 1933. P. 21.)

May 20-21, 1840“Now there has been an unusual drought since spring, [forest] fires are still going on, usually ending with heavy rains. Today we were pleased with the rain, which lasted no more than an hour, but still gave some moisture and will help the seedlings of bread and grass.” 1 .

1 (Bestuzhevs Mikhail and Nikolai: Letters from Siberia. Irkutsk: Vosg.-Sib. book publishing house, 1933. P. 41.)

Selenginsk did not resemble an earthly paradise for a farmer. Nikolai Bestuzhev later wrote in “Goose Lake” that a characteristic feature of the climate of Transbaikalia is frequent droughts. Only the spring of 1852 “promised us good harvests.” According to him, “the bread and herbs sprouted beautifully, but according to a 12-year habit, nature refused us rain until the beginning of June, and therefore all the seedlings burned out” 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N.A. Stories and tales of an old sailor. St. Petersburg, 1861. P. 504.)

However, subsequent years were also unfavorable for farmers. “I don’t know about you,” Nikolai Bestuzhev wrote to Ivan Pushchin on June 24, 1854, “but our summer is completely different from summer. Spring began in March; in April it was 22° in the shade, but in May the cold began: 27 On the 10th of June, at the very solstice, there was frost and a frost of 1°; then there were torrential rains, flooding basements, cellars, washing away all the gardens and ruining all the roads. But there were warm days, sultry, like in Africa The droughts were such that forests were burning all around, and I had to live for a whole week between the fire and strong winds in order to extinguish the fire, which threatened to destroy all our mowing and harvesting standing on it, and now I can barely hold a pen in my burnt hand" 1 .

1 (Bestuzhev N. A. Articles and letters. P. 271.)

Bestuzhev noticed that frequent forest fires and the irrational destruction of former dense forests led to a decrease in the water reserves that fed rivers and streams. “The swamps have dried up,” he wrote to his sister Elena, “the rivers have dried up, the springs have dried up.” All this led to a sharp change in climatic conditions, to frequent droughts and associated crop shortages, although in previous years the harvests were almost fabulous 1 .

1 (Bestuzhevs Mikhail and Nikolai: Letters from Siberia. P. 24.)

The influence of meteorological conditions on the harvest and the ripening of grass became the subject of Bestuzhev’s study. (At the same time, not only scientific, but also certain practical interests were pursued, since Bestuzhev received a plot of land and earned his livelihood by cultivating it.) But even earlier, his friend, Thorson, a participant in the First Russian expedition to the South Pole, took up these issues.

Today's researchers, who have extensive and long-term meteorological data, believe that “the first half of summer in Transbaikalia is characterized by unfavorable climatic conditions for the development of agricultural crops” 1 . This feature of the climate of Transbaikalia was one of the first to notice by Bestuzhev and Thorson. Moreover, they were the first to draw attention to the insignificant amount of precipitation, especially in winter, to the great dryness of the air, to frequent sandstorms and frosts.

1 (Shcherbakova E. Ya. Climate of the USSR. L.: Gidrometeozdat, 1971.)

Bestuzhev tried to identify the relationship between seismic and hydrometeorological phenomena and, keeping his own meteorological journal, noted the striking agreement between the “loss and gain of water” in the Selenga River with the earthquakes that were often observed in the vicinity of Selenginsk 1 .

1 (Vol. 5: Eastern Siberia." P. 225. 87 Streich S., Ya, Sailors-Decembrists. M.: Voenmorizdat, 1946. P. 221.)

The Decembrist followed news about the weather in various regions of the globe and tried to compare its course with the course of atmospheric processes in Selenginsk. “For some time now,” he wrote to his brother Pavel on April 26, 1844, “the climate here has completely changed, and I don’t know whether this atmospheric revolution will return to its previous order. All over Europe they are complaining about the climate change; where there is constant cold, where there is no cold at all.” winters, where there is rain, where there is rain and flood, and where there is drought. In our country, where the climate has always been equal at certain times of the year, incessantly cruel winds blow and, as a result, there is an endless drought."

1 (IRLI. F. 604. Op. 1. D. 4. L. 166. N. A. Bestuzhev - P. A. Bestuzhev.)

Even with the meager information about the weather that was received in Selenginsk (newspapers and magazines at that time were delivered to Siberia by postal trains several weeks and even months after their publication), Bestuzhev noted the anomalous features of atmospheric processes in the early 40s XIX century They attracted the attention of many meteorologists, including A.I. Voeikov.

Bestuzhev highly appreciated the successes of domestic meteorology, so he welcomed the creation of a regular, permanent geophysical network, the publication of its observations and the founding of the Main Physical Observatory as a significant event in the scientific life of Russia. Bestuzhev wrote to Sviyazev: “There are workers of science whose name sounds pleasantly in the ear of every educated person: these are the names of Struve, Kupfer, especially since they are our Russian scientists from whom foreigners come to study. The management of a physical and magnetic observatory, a set of meteorological observations throughout "Russia is a huge work, an invaluable work for science and for humanity, which is trying to lift the veil behind which nature keeps its secrets. Living even here, I know what kind of trouble it takes to collect observations from magnetic observatories built throughout Russia..." 1 .

1 ()