“This is how we learned in Rus'” Excursion into history. What kind of schools were there in Rus' in the old days? What was taught in the first schools in Rus'

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOW WE TAUGHT AND LEARNED IN ANCIENT Rus'

The temptation to “look” into the past and “see” a bygone life with one’s own eyes overwhelms any historian-researcher. Moreover, such time travel does not require fantastic devices. An ancient document is the most reliable carrier of information, which, like a magic key, unlocks the treasured door to the past. This blessed opportunity for a historian was given to Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev, a famous journalist and writer in the 19th century. His historical monograph “Russian School Books” was published in 1861 in the fourth book of “Readings in the Society of Russian History and Antiquities at Moscow University.” The work is dedicated to the ancient Russian school, about which at that time (and indeed even now) so little was known.

... And before this, there were schools in the Russian kingdom, in Moscow, in Veliky Novograd and in other cities... They taught literacy, writing and singing, and honor. That’s why there were many people who were very good at reading and writing, and scribes and readers were famous throughout the land.

From the book "Stoglav"

Many people are still confident that in the pre-Petrine era in Rus' nothing was taught at all. Moreover, education itself was then allegedly persecuted by the church, which only demanded that students somehow recite prayers by heart and little by little sort out printed liturgical books. Yes, and they taught, they say, only the children of the priests, preparing them for taking orders. Those of the nobility who believed in the truth “teaching is light...” entrusted the education of their offspring to foreigners discharged from abroad. The rest were found “in the darkness of ignorance.”

Mordovtsev refutes all this. In his research, he relied on an interesting historical source that fell into his hands - “Azbukovnik”. In the preface to the monograph dedicated to this manuscript, the author wrote the following: “Currently, I have the opportunity to use the most precious monuments of the 17th century, which have not yet been published or mentioned anywhere and which can serve to explain the interesting aspects of ancient Russian pedagogy. Materials these are contained in a lengthy manuscript bearing the name “Azbukovnik” and containing several different textbooks of that time, written by some “pioneer”, partly copied from other, similar publications, which were entitled with the same name, although they differed in content and had different counts of sheets."

Having examined the manuscript, Mordovtsev makes the first and most important conclusion: in Ancient Rus', schools as such existed. However, this is also confirmed by an older document - the book “Stoglav” (a collection of resolutions of the Stoglav Council, held with the participation of Ivan IV and representatives of the Boyar Duma in 1550-1551). It contains sections that talk about education. In them, in particular, it is determined that schools are allowed to be maintained by persons of clergy rank, if the applicant receives permission from the church authorities. Before issuing one to him, it was necessary to test the thoroughness of the applicant’s own knowledge, and collect possible information about his behavior from reliable guarantors.

But how were the schools organized, how were they managed, and who studied in them? “Stoglav” did not give answers to these questions. And now several handwritten “Azbukovniks” - very interesting books - fall into the hands of a historian. Despite their name, these are, in fact, not textbooks (they contain neither the alphabet, nor copybooks, nor teaching numeracy), but rather a guide for the teacher and detailed instructions for students. It spells out the student’s complete daily routine, which, by the way, concerns not only school, but also the behavior of children outside of it.

Following the author, we too will look into the Russian school of the 17th century; fortunately, “Azbukovnik” gives full opportunity to do so. It all starts with the arrival of children in the morning to a special home - a school. In various ABC books, instructions on this matter are written in verse or prose; they, apparently, also served to strengthen reading skills, and therefore the students persistently repeated:

In your house, having risen from sleep, washed yourself,

Wipe the edge of the board well,

Continue in the veneration of holy images,

Bow low to your father and mother.

Go to school carefully

And lead your comrade,

Enter school with prayer,

Just go out there.

The prose version also teaches about the same thing.

From "Azbukovnik" we learn a very important fact: education in the times described was not a class privilege in Rus'. In the manuscript, on behalf of “Wisdom,” there is an appeal to parents of different classes to send their children to be taught “extreme literature”: “For this reason I speak continually and will never cease in the hearing of pious people, of every rank and dignity, glorious and honorable, rich and wretched, even to the last farmers." The only limitation to education was the reluctance of the parents or their sheer poverty, which did not allow them to pay the teacher anything for educating their child.

But let us follow the student who entered the school and had already placed his hat on the “common bed,” that is, on the shelf, bowed to the images, and to the teacher, and to the entire student “squad.” A student who came to school early in the morning had to spend the whole day there until the bell rang for the evening service, which was the signal for the end of classes.

The teaching began with the answer to the lesson studied the day before. When the lesson was told by everyone, the whole “squad” performed a common prayer before further classes: “Lord Jesus Christ our God, creator of every creature, give me understanding and teach me the scriptures of the book, and hereby we will obey Your desires, for I will glorify You forever and ever, Amen !"

Then the students approached the headman, who gave them the books they were to study from, and sat down at a common long student table. Each one took the place assigned to him by the teacher, observing the following instructions:

The malia in you and the greatness are all equal,

For the sake of the teachings, let them be noble...

Do not disturb your neighbor

And don’t call your friend by his nickname...

Don't be close to each other,

Do not use your knees and elbows...

Some place given to you by the teacher,

Let your life be included here...

Books, being the property of the school, constituted its main value. The attitude towards the book was reverent and respectful. It was required that the students, having “closed the book,” always put it with the seal facing up and did not leave “indicative trees” (pointers) in it, did not unbend it too much and did not leaf through it in vain. It was strictly forbidden to place books on the bench, and at the end of the lesson, the books had to be given to the headman, who put them in the designated place. And one more piece of advice - do not get carried away by looking at book decorations - “tumbles”, but strive to understand what is written in them.

Keep your books well

And put it in a dangerous place.

...The book, closed, sealed to height

I guess

There is no index tree in it at all

don't invest...

Books to the elder for observance,

with prayer, bring,

Taking the same thing in the morning,

with respect, please...

Don’t unbend your books,

And don’t bend the sheets in them either...

Books on the seat

Do not leave,

But on the prepared table

please supply...

Who doesn’t take care of books?

Such a person does not protect his soul...

The almost verbatim coincidence of phrases in the prose and poetic versions of different “Azbukovniki” allowed Mordovtsev to assume that the rules reflected in them were the same for all schools of the 17th century, and therefore, we can talk about their general structure in pre-Petrine Rus'. The same assumption is prompted by the similarity of the instructions regarding the rather strange requirement that prohibits students from talking outside the school walls about what is happening in it.

Leaving home, school life

don't tell me

Punish this and every one of your comrades...

Ridiculous words and imitation

don't bring it to school

Do not wear out the deeds of those who were in it.

This rule seemed to isolate the students, closing the school world into a separate, almost family community. On the one hand, it protected the student from the “unhelpful” influences of the external environment, on the other hand, it connected the teacher and his students with special relationships inaccessible even to close relatives, and excluded the interference of outsiders in the process of teaching and upbringing. Therefore, to hear from the lips of the then teacher the now so often used phrase “Don’t come to school without your parents” was simply unthinkable.

Another instruction, similar to all “Azbukovniki,” speaks of the responsibilities that were assigned to students at school. They had to “add up the school”: sweep away the rubbish, wash the floors, benches and tables, change the water in the vessels under the “light” - a stand for a torch. Lighting the school with the same torch was also the responsibility of the students, as was firing the stoves. The head of the school “team” assigned students to such work (in modern language, on duty) in shifts: “Whoever heats the school, installs everything in that school.”

Bring fresh water vessels to school,

Take out the tub of stagnant water,

The table and benches are washed cleanly,

Yes, it is not disgusting for those who come to school;

This way your personal beauty will be known

You will also have school cleanliness.

The instructions urge students not to fight, not to play pranks, and not to steal. It is especially strictly prohibited to make noise in and around the school itself. The rigidity of this rule is understandable: the school was located in a house owned by the teacher, next to the estates of other residents of the city. Therefore, noise and various “disorders” that could arouse the anger of neighbors could well turn into a denunciation to the church authorities. The teacher would have to give the most unpleasant explanations, and if this is not the first denunciation, then the owner of the school could “be subject to a ban on maintaining the school.” That is why even attempts to break school rules were stopped immediately and mercilessly.

In general, discipline in the ancient Russian school was strong and severe. The whole day was clearly outlined by rules, even drinking water was allowed only three times a day, and “going to the yard for the sake of need” was only possible with the permission of the headman only a few times. This paragraph also contains some hygiene rules:

For the sake of need, who needs to go,

Go to the headman four times a day,

Come back from there immediately,

Wash your hands to keep them clean,

Whenever you go there.

All "Azbukovnik" had an extensive section - about the punishment of lazy, careless and obstinate students with a description of the most diverse forms and methods of influence. It is no coincidence that “Azbukovniki” begins with a panegyric to the rod, written in cinnabar on the first page:

God bless these forests,

The same rods will give birth for a long time...

And it’s not just “Azbukovnik” that praises the rod. In the alphabet, printed in 1679, there are these words: “The rod sharpens the mind, awakens the memory.”

However, one should not think that he used the power that the teacher possessed beyond all measure - good teaching cannot be replaced by skillful flogging. Nobody would teach someone who became famous as a tormentor and a bad teacher. Innate cruelty (if any) does not suddenly appear in a person, and no one would allow a pathologically cruel person to open a school. How children should be taught was also discussed in the Code of the Stoglavy Council, which was, in fact, a guide for teachers: “not with rage, not with cruelty, not with anger, but with joyful fear and loving custom, and sweet teaching, and gentle consolation.”

It was between these two poles that the path of education lay somewhere, and when the “sweet teaching” was of no use, then a “pedagogical instrument” came into play, according to experts, “a sharpening mind, stimulating the memory.” In various "Azbukovniks" the rules on this matter are set out in a way that is understandable to the most "rude-minded" student:

If anyone becomes lazy with teaching,

Such a wound will not be ashamed...

Flogging did not exhaust the arsenal of punishments, and it must be said that the rod was the last in that series. The naughty boy could be sent to a punishment cell, the role of which was successfully played by the school “necessary closet”. There is also a mention in “Azbukovniki” of such a measure, which is now called “leave after school”:

If someone doesn't teach a lesson,

One from free school

won't receive...

However, there is no exact indication whether the students went home for lunch in “Azbukovniki”. Moreover, in one of the places it is said that the teacher “during the time of bread-eating and midday rest from teaching” should read to his students “useful writings” about wisdom, about encouragement for learning and discipline, about holidays, etc. It remains to be assumed that Schoolchildren listened to this kind of teaching during a common lunch at school. And other signs indicate that the school had a common dining table, maintained by the parents' contribution. (However, perhaps this particular order was not the same in different schools.)

So, the students were constantly at school for most of the day. In order to have the opportunity to rest or be absent on necessary matters, the teacher chose an assistant from among his students, called the headman. The role of the headman in the internal life of the then school was extremely important. After the teacher, the headman was the second person in the school; he was even allowed to replace the teacher himself. Therefore, the choice of a headman for both the student “squad” and the teacher was the most important matter. "Azbukovnik" prescribed that the teacher himself should select such students from among the older students who were diligent in their studies and had favorable spiritual qualities. The book instructed the teacher: “Keep on your guard against them (that is, the elders. - V.Ya.). The kindest and most skillful students who can announce them (the students) even without you. V.Ya.) a shepherd's word."

The number of elders is spoken of differently. Most likely, there were three of them: one headman and two of his assistants, since the circle of responsibilities of the “chosen ones” was unusually wide. They monitored the progress of school in the absence of the teacher and even had the right to punish those responsible for violating the order established in the school. They listened to the lessons of younger schoolchildren, collected and gave out books, monitored their safety and proper handling. They were in charge of "leave to the yard" and drinking water. Finally, they managed the heating, lighting and cleaning of the school. The headman and his assistants represented the teacher in his absence, and in his presence - his trusted assistants.

The headmen carried out all the management of the school without any reporting to the teacher. At least, that’s what Mordovtsev thought, not finding a single line in “Azbukovniki” that encouraged fiscalism and gossip. On the contrary, students were taught in every possible way to comradeship, to life in a “squad”. If the teacher, looking for the offender, could not accurately point to a specific student, and the “squad” did not give him away, then the punishment was announced to all students, and they chanted in chorus:

Some of us have guilt

Which was not before many days,

The culprits, hearing this, blush their faces,

They are still proud of us, the humble ones.

Often the culprit, in order not to let down the “squad,” removed the ports and himself “climbed onto the goat,” that is, he lay down on the bench, on which the “assignment of lozans to fillet parts” was carried out.

Needless to say, both the teaching and the upbringing of the youths were then imbued with deep respect for the Orthodox faith. What is invested from a young age will grow in an adult: “This is your childhood, the work of students in school, especially those who are perfect in age.” Students were required to go to church not only on holidays and Sundays, but also on weekdays, after finishing school.

The evening bell signaled the end of the teaching. “Azbukovnik” teaches: “When you are released, you all rise up in droves and give your books to the bookkeeper, with a single proclamation everyone, collectively and unanimously, chant the prayer of St. Simeon the God-Receiver: “Now do you let go of Your servant, Master” and “Glorious Ever-Virgin.” After this, the disciples were to to go to vespers, the teacher instructed them to behave decently in church, because “everyone knows that you are studying at school.”

However, demands for decent behavior were not limited to school or temple. The school rules also extended to the street: “When the teacher dismisses you at such a time, go home with all humility: jokes and blasphemies, kicking each other, and beating, and running around, and throwing stones, and all sorts of similar childish mockery, let it not dwell in you." Aimless wandering through the streets was also not encouraged, especially near all sorts of “entertainment establishments,” then called “disgraces.”

Of course, the above rules are better wishes. There are no children in nature who would refrain from “spitting and running around”, from “throwing stones” and going to “disgrace” after they spent the whole day at school. In the old days, teachers also understood this and therefore sought by all means to reduce the time students spent unsupervised on the street, which pushed them into temptations and pranks. Not only on weekdays, but on Sundays and holidays, schoolchildren were required to come to school. True, on holidays they no longer studied, but only answered what they had learned the day before, read the Gospel aloud, listened to the teachings and explanations of their teacher about the essence of the holiday of that day. Then everyone went to church together for the liturgy.

The attitude towards those students whose studies were going poorly is curious. In this case, “Azbukovnik” does not at all advise them to flog them intensively or punish them in any other way, but, on the contrary, instructs: “whoever is a “greyhound learner” should not rise above his fellow “rough learner.” The latter were strongly advised to pray, calling on God for help. And the teacher worked with such students separately, constantly telling them about the benefits of prayer and giving examples “from scripture,” talking about such ascetics of piety as Sergius of Radonezh and Alexander of Svirsky, to whom teaching was not at all easy at first.

From "Azbukovnik" one can see the details of a teacher's life, the subtleties of relationships with students' parents, who paid the teacher, by agreement and if possible, payment for the education of their children - partly in kind, partly in money.

In addition to school rules and procedures, "Azbukovnik" talks about how, after completing primary education, students begin to study the "seven free arts." By which were meant: grammar, dialectics, rhetoric, music (meaning church singing), arithmetic and geometry (“geometry” was then called “all land surveying,” which included geography and cosmogony), and finally, “the last one, but The first action" in the list of sciences studied then was called astronomy (or in Slavic "star science").

And in the schools they studied the art of poetry, syllogisms, studied celebras, the knowledge of which was considered necessary for “virtuous diction”, became acquainted with “rhyme” from the works of Simeon of Polotsk, learned poetic measures - “one and ten kinds of verse.” We learned to compose couplets and maxims, write greetings in poetry and prose.

Unfortunately, the work of Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev remained unfinished, his monograph was completed with the phrase: “The Reverend Athanasius was recently transferred to the Astrakhan Diocese, depriving me of the opportunity to finally parse the interesting manuscript, and therefore, not having the ABC Books at hand, I was forced to finish my "The article is where it left off. Saratov 1856."

And yet, just a year after Mordovtsev’s work was published in the journal, his monograph with the same title was published by Moscow University. The talent of Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev and the multiplicity of topics touched upon in the sources that served to write the monograph, today allow us, with minimal “speculation of that life,” to make a fascinating and not without benefit journey “against the flow of time” into the seventeenth century.

V. YARKHO, historian.

Daniil Lukich Mordovtsev (1830-1905), having graduated from a gymnasium in Saratov, studied first at Kazan University, then at St. Petersburg University, from which he graduated in 1854 from the Faculty of History and Philology. In Saratov he began his literary activity. He published several historical monographs, published in “Russian Word”, “Russian Bulletin”, “Bulletin of Europe”. The monographs attracted attention, and Mordovtsev was even offered to occupy the department of history at St. Petersburg University. Daniil Lukich was no less famous as a writer on historical topics.

From Bishop Afanasy Drozdov of Saratov, he receives handwritten notebooks from the 17th century telling about how schools were organized in Rus'.

This is how Mordovtsev describes the manuscript that came to him: “The collection consisted of several sections. The first contains several ABC books, with a special count of notebooks; the second half consists of two sections: in the first - 26 notebooks, or 208 sheets; in the second, 171 sheets The second half of the manuscript, both of its sections, were written by the same hand... The entire section, consisting of “Azbukovnikov”, “Pismovnikov”, “School deaneries” and others - up to page 208, was written in the same hand. in handwriting, but with different ink it is written up to the 171st sheet and on that sheet, in a “four-pointed” cunning secret script, it is written “Started in the Solovetsky Hermitage, also in Kostroma, near Moscow in the Ipatskaya monastery, by the same first wanderer in the year of world existence 7191 (1683 .)".

“Schools in Rus'” - What is needed for the lesson? What was taught in schools? Class teacher Nikiforova E.V. 2011. XI – XV centuries. B.M. Kustodiev “School in Muscovite Rus'”. How did they teach in schools in Rus'? How did you study in Rus'? When did the first schools appear? She wrote birch bark letters, waxed tablets. The first schools in Rus' were opened in the 10th century by decree of Prince Vladimir.

“Russian customs” - In Ancient Rus', the Nativity of Christ meant the beginning of winter. Wednesday is delicious. On Monday we celebrated Maslenitsa. Warm-up questions. Medicinal plants were collected. What are the holidays between Christmas and Epiphany called? Then fires were lit and round dances were held. Epiphany of the Lord is celebrated on January 19. In the old days, our ancestors went to swim in rivers, ponds, and lakes.

“Dolmen” - Purpose of the lesson: C) trough-shaped - that is, knocked out entirely in a rock block, but covered with a separate slab; To date, more than 2,300 dolmens are known in the Kuban and Black Sea regions. Dolmen - translated from Breton language means “stone table”. Total weight: from 6795 to 25190 kg. Dolmens can be very diverse in shape and material.

“Christmastide” - What are Christmastide? They believed that God would punish those who worked on Christmastide: a person who weaves bast shoes on Christmas Eve evenings would have crooked cattle, and someone who sews clothes would have their cattle go blind. Christmas time. Christmastide was usually celebrated in the evening and at night: daytime was reserved for daily work, and only with the onset of darkness did the peasants put aside their work and take part in entertainment and perform various kinds of rituals.

“Russian national cuisine” - Modern cuisine from 1917 to the present 5. Old Russian cuisine of the 9th-16th centuries.2. Kitchen of the Peter and Catherine era of the 18th century. Soups remained of primary importance in the history of Russian cuisine. Modern kitchen from 1917 to the present 1. The spoon has always been the main cutlery of Russians. Cuisine of the Moscow state of the 17th century.

“Izba” - Men’s corner, or “konik” - at the entrance. The ceiling beams were laid on a massive beam - the matrix. 6-walled communication hut. Since the 15th century, stoves with pipes have become widespread. A ring for the ochepa was screwed into the mat. The interior walls were whitewashed and lined with planks or linden boards. The clergy sat down in a large place without refusing.

There are a total of 39 presentations in the topic

An intelligent, literate, learned person in Rus' has always been revered and said: “The bird is red with the feather, and the man with the mind,” “The head is the beginning of everything,” “And strength is inferior to the mind.” “Great is the benefit of book learning,” the chronicler wrote in the ancient Russian chronicle. The path to book knowledge began with mastering the alphabet. “First Az and Buki, and then science.”

Each letter of the Old Russian alphabet had its name as a specific word starting with this letter. For example, the letter “L” means “people”, the letter “P” means “peace”, the letter “F” means “live”. And so with all the letters. This alphabet was called “Cyrillic”, in honor of its creator, the enlightener of the Slavs, St. Cyril.

It is now difficult for us to establish exactly how literacy was taught in Ancient Rus', because this was many, many years ago. But historians, studying surviving records, ancient riddles, proverbs, sayings, suggest how this learning could take place.

Most likely, at the age of 7–10, children were sent to a “master of literacy” (as the teacher was called then). One teacher gathered about a dozen children at his home and taught them. First we learned the alphabet. The students repeated each letter in chorus until they memorized it. Since then the proverb has been preserved:

“They teach the alphabet, they shout at the whole hut.”

But it was not a random cry, but a repetition in a chant. This “singing” of the alphabet made memorization easier.

After the letters, syllables were learned. First, the children had to name the letters as they were called in the alphabet, and then name the syllable (combination of letters):“buki-az” – “ba”, “vedi-az” – “va” and further.

At the same time as reading, they learned to write. To do this, at first they used a wooden plank with a rectangular recess filled with soft wax. Such a tablet was called “tsera”. It was covered on top, like a lid, with another board. Ribbons were threaded into the holes on the sides: they were tied and the result was a double-leaf notebook with an empty middle. A riddle was invented about such an unusual ancient Russian notebook:“The book has two pages, and the middle is empty.”

They wrote on wax with a writing rod - a metal rod, one end of which was sharpened (with this end they scratched out the text), while the other end was flattened (it turned out to be a small spatula that could be used to smooth out the wax when they wanted to erase what was written). The writing rod was often twisted to make it easier to hold. Students carried such a writing instrument in a special case suspended from their belts.

When the children learned to write on a board covered with wax, they moved on to writing on birch bark. In Ancient Rus', birch bark - birch bark - served as the main material for writing. Of course, it is more difficult to write on hard birch bark than on soft wax. I had to learn to write letters and words again. Children often kept a writing board or birch bark not on the table, but on their knee. And so, bending over, they wrote. It turned out that writing is not such an easy task.

“It seems like writing is an easy task, you write with two fingers, but your whole body hurts.”

During excavations in Novgorod, archaeological scientists found birch bark letters that belonged to the boy Onfim, who lived more than 700 years ago. On pieces of birch bark, Onfim, practicing, wrote letters, syllables, words.

What books were used for learning in Rus' in the old days? Church books were educational: the Book of Hours and the Psalter.

Books were then written on parchment, a specially treated leather. If necessary, the “leather” pages could be reused: a sharp knife was used to scrape off what was written, and the sheet became clean again. The writing on the parchment was stable, the ink was well absorbed, and the outlines of the letters were preserved even after several washes of the previous texts. This feature is conveyed by the proverb:

“What is written with a pen cannot be cut out with an axe.”

But books written on parchment were expensive, so teachers often copied passages of text from books onto birch bark or wrote “small books” for children upon orders from parents.

You can tell a lot of interesting things about ancient Russian books. Do you know, for example, this saying: “Read from blackboard to blackboard”? When they say this, they mean reading the book from beginning to end. And this saying came to us from Ancient Rus', where, for preservation, so that they would not wear out so quickly, books were bound in wooden planks. The boards were sometimes covered with leather. The cover of a closed book was fastened with metal fasteners over the binding. The boards were often decorated with overlays made of copper, bronze, and bone. Archaeologists found many such metal and bone plates; these details were preserved even when the books themselves were destroyed during fires, floods and other incidents.

Books were written, as you already know, on parchment. This required ink. The students made their own ink from a mixture of soot and glue or from growths on oak leaves.

They wrote on parchment with quills. Before writing, they were carefully processed: first, the fat was scraped off from them, then they were stuck into heated sand or ash, then unnecessary membranes were removed and the pen was sharpened, after which the end was split in half.

Here are two old Russian riddles. What do you think, which of them talks about writing, which was used to write on wax and birch bark, which one talks about a pen?

A small horse takes water from a black lake and waters a white field.

Five oxen plow with one plow.

Of course, the first riddle is about a quill pen, and in the second, the “five oxen” are the five fingers of the hand that hold the pen and, with effort, scratch out letters with it, as if they were plowing.

The ink was stored in a clay or cow horn inkwell. Sometimes they wrote with ink on birch bark.

When writing, a quill pen often left blots. They were washed with a porous stone or, until they dried out... licked off with the tongue. A riddle about the writing process has reached our times:

“They sow the gray seed with their hands and lick it off with their tongue.”

There was another difficulty - writing on parchment did not dry out for a long time. Therefore, the written text was sprinkled with sand, which immediately absorbed the top layer of ink. Each student carried an inkwell and a bag of sand to school. They were connected by a cord that was worn around the neck. At that time a saying arose:

“The sandbox is the friend of the inkwell.”

In Rus', until the last century, the ancient custom of celebrating the end of literacy training with a common meal - lunch - was preserved.

Historian I. Zabelin discovered an interesting record that was kept in the personal archive of the famous Russian actor Mikhail Shchepkin, who at the end of the 18th century studied at school using ancient methods. Here is the text:

“I remember that during the change of books, that is, when I finished the alphabet and brought the Book of Hours to school for the first time, I immediately brought a pot of milk porridge, wrapped in a scarf, and half a piece of money, which, as a tribute following the teaching, along with the scarf was given to the teacher. The porridge was usually placed on the table and, after repeating what had been learned in the last lesson, spoons were distributed to the students, with which they grabbed the porridge from the pot... After the end of the Book of Hours, when I brought the Psalter, the same procession was repeated again.”

Since students moved to new stages of learning at different times, there were several such meals and lunches throughout the year.

The custom of offering porridge changed the child’s position among the disciples. They celebrated successful progress in their studies. The very act of bringing porridge to the teacher, according to the rules of that time, was a form of expressing respect to the teacher.

But the main thing is that they treated literacy with reverence, and their teachers were greatly revered and respected. Book understanding was considered a gift from God. And therefore, those who sought to master literacy, and then the sciences, combined teaching with prayer. They relied on God’s gracious help, and not only on their own strength and skill as a teacher.

If the teaching was difficult, the student did not succeed in many things, the whole family, having invited a priest, served a prayer service to the Savior, the Mother of God and the patron saints in the teaching: Cosmas and Damian, the prophet Naum (just in those days of the end of autumn, when the Church celebrated their memory, the school year usually began in ancient Russian peasant schools). They turned to the saints in prayer, the Prophet Nahum was directly asked: “Prophet Nahum, guide the child to mind.” Later they began to pray for incapable and careless students to St. Sergius of Radonezh.

Let us also ask God for admonition through prayer:

Most gracious Lord, bestow upon us the grace of Your Holy Spirit, strengthening our spiritual strength, so that, by heeding the teaching, we may grow to You, our Creator, for glory, for our parents as a consolation, for the benefit of the Church and the Fatherland.

MBOU "Kilemar Secondary School"

Lesson for Knowledge Day

(as part of events for the 110th anniversary of the school)

How children studied in the old days

Extracurricular activity

Sorokina Elena Viktorovna,

primary school teacher

MBOU "Kilemarskaya Secondary School"

2012

Goals:

Introducing students to the history of their Fatherland.

Formation of motivation to study.

Fostering love for your homeland.

Progress of the event

Reading the sentence aloud by students: “Jump with literacy, even cry without literacy.”

Teacher:

Explain the meaning of this proverb.

(slide 2)

(All roads are open to the literate, but life is very difficult for the illiterate)

As years, decades, centuries pass, do you think schoolchildren’s education changes?

Have you ever wondered how schoolchildren were taught before? What would you like to know?

Student answers:

When did the first school appear?

– How did our peers study?

What kind of textbooks did they have?

– What subjects were taught?

– How long did the lessons last?

– Who was the teacher?

Teacher:

So, determine the topic of our lesson.

Students:

How did schoolchildren study in the old days?

Teacher:

Guys, to get answers to your questions, I invite you and our guests to take a trip to the distant past

Teacher:

In ancient times, the people of Rus' were mainly engaged in agriculture. From early spring to late autumn, peasants worked in the fields to feed their families.

But now it's winter. The harvest has been harvested. Empty in the field and on the street. Silence all around... Although, no! Hear: song! These are the girls gathered for a get-together, working, singing their favorite tune. (Ivan Kupala “Youth”)

And the children are not visible on the street...

Oh yes! After all, they are learning! In the old days, according to ancient custom, children were sent to study on the day of the holy prophet Nahum (slide 3), popularly called the Grammar. And the people said this: “Prophet Nahum will guide the mind.” This day is celebrated December 14 . It was no coincidence that this day was called “wise” and they prayed to Saint Naum, asking him to “bring to mind” - to advise, to teach.

So, on this day, parents blessed their children to study. And the disciples themselves asked Saint Naum “Father Naum, bless your mind!”

(slide3)

Student: (Krasheninnikova Anna)

They raised the children early that day and said:

Wake up early

Wash your face white,

Gather to God's church,

Get to grips with your ABCs!

Pray to God -

You'll get to everything:

Saint Naum will guide you to your mind.

Teacher:

On December 14, having dressed up, everyone went to the church, where after the Liturgy they served a prayer service, asking for blessings on the youth’s teaching. Boys 10-12 years old and teenagers were called adolescents.

After the church service, the teacher greeted the student with honor at his home, seated him in the best place, treated him with food and gifts.Teachers were especially revered, considering his work extremely important and difficult.

The father handed his son over to the teacher with a request not to feel sorry for him, but to teach him wisdom, and treat him with beatings for laziness. And the mother had to cry, otherwise bad rumors would spread. The son made three prostrations to the teacher, and the teacher hit the student on the back three times with a whip... in advance, so that the boy would not be mischievous, but would study diligently, so that he would appreciate the seriousness and benefits of study.As a reward for their efforts, father and mother presented the teacher with a loaf of bread and a towel, in which they tied money as payment for classes. But most often, classes were paid for with food: the student’s mother brought the teacher a chicken, a basket of eggs or a pot of buckwheat porridge.

The next day the student was sent to the teacher with the alphabet and a pointer. And before the lesson, the children read a prayer:“Holy prophet, God’s Nahum, give me understanding”

Teacher:

The lesson has already started. Let's slowly, so as not to disturb the little schoolchildren, take a look into the classroom.

Conversation on the reproduction of B.M. Kustodiev “School of Moscow Rus'”

(slide 4.5)

Do you think the school of that time was similar to the modern one?

Consider a reproduction of a painting by B.M. Kustodiev, who dedicated his work to the historical theme “School of Moscow Rus'”.

What's special about this class?

What are the students doing? How many are there?

Can you tell how they feel about teaching?

How is this school different from the modern one?

You correctly noted the differences between the school of Ancient Rus' and the modern one, and now listen to a poem about the school of Ancient Rus' by N. Konchalovskaya, which the students of our class will tell us. After listening to it, you will talk about the differences between schools that we have not yet talked about.

Student : reading a poem“And in the old days children studied” by heart.

And in the old days children studied - (Dmitry Batrakov)

They were taught by the church clerk, -

They came at dawn

And the letters repeated like this:

A and B - like Az and Buki,

V - like Vedi, G - Verbs

And a teacher for science

On Saturdays I flogged everyone.

That's how wonderful it is at the beginning

Our diploma was there!

This is the pen they wrote with -

From a goose feather!

This knife is for a reason

It was called a penstock:

They sharpened their pen,

If it wasn't spicy.

Diploma was difficult (Ekaterina Ivantsova)

To our ancestors in the old days,

And the girls were supposed to

Don't learn anything.

Only boys were trained.

Deacon with a pointer in his hand

I read books to them in a sing-song manner

In Slavic language.

So from the chronicles of old

Muscovite children knew

About Lithuanians, about Tatars,

And about your homeland.

N. Konchalovskaya.

So, what else did you learn about the school of Ancient Rus' from the work you listened to? (Children studied at dawn. Only boys studied in schools. They were taught by a clerk in the Slavic language. On Saturdays, students were flogged. Previously, they wrote not with a pen, but with a quill pen.)

Physical exercise.

Children dance to the Russian folk song “Kolyada” performed by the group “Ivan Kupala”, repeating the movements of the student dancing at the blackboard.

A story about the history of writing.

Previously, children were taught to write only after a year, when the alphabet was learned. The following students will tell us about what and how they wrote. (Creative homework was given: prepare a message on this topic.)

Student: message“What did you write on and how?”

(Mikhailov Anton ) Previously, people wrote with a sharp stick on white birch bark, with a needle on palm leaves, on clay tablets, on wax-coated tablets and even on copper sheets.

(Serebryakova Nastya) In Rus' they wrote on parchment. Parchment was made from the skin of goats, calves, and sheep. The skin was carefully cleaned, scraped, polished until it turned white or yellow. They wrote on parchment clearly and beautifully. It was expensive; no one would have dared to write on it. Several sheets of parchment made up a book. One book was written over many months, sometimes even years.

Teacher's addition to the child's report:

In modern schools, children write in notebooks, but previously this word had a different meaning. Books were first written on scrolls, and later on sheets folded in half, combined into groups of 4 sheets. Such books were called notebooks.

Notebook - (Greek - four) sheets folded into four on which to write.

The history of the alphabet.

Teacher: Before people in Ancient Rus' learned to write, they studied letters. Who invented the Russian alphabet? (children's answers)

The alphabet that we now use was created by the Slavs, the brothers Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. (Slide 6) Cyril and Methodius compiled the alphabet, and then translated some sacred scriptures into Slavic. Some of the letters were borrowed from the Greek alphabet, and some were specially created to convey those sounds of the Slavic language that were not in the Greek language. These are the letters: B, Zh, C, Ch, Sh, U, Yu, Z. There were 45 letters in the alphabet. This alphabet was called Cyrillic in honor of one of the brothers who founded it.

Teacher:

Let's ask the students to read something from their alphabet and try to translate it into a modern language.

(slide 7)

you're thinking, you're thinking,(Mother)

he thinks well(house)

sha koko he people az(school)

Teacher : In the ancient school there were no breaks, no principal, and only one teacher. The training went on from morning to evening; in the middle of the day there is a break for students to have lunch. The rules were strict: you could only drink three times the whole day, and only go out twice to relieve yourself.

They were especially taught to handle books with care; they could not be placed on the bench, but only on the table.

So from dark to dark, lessons went on in the ancient Russian school. Each student received a personal assignment from the teacher: one took the first steps, another moved on to the “warehouses,” the third was already reading the Book of Hours. And everything had to be learned “by heart”, “by rote”. Everyone taught their own out loud. No wonder they put together a proverb: “They teach the alphabet - they shout at the top of their voices”.

For disobedience and unlearned lessons, the teacher, as they used to say, “crushed the ribs” with rods. A picture of a rod was even placed at the beginning of the textbook and written:“The rod sharpens the mind, awakens the memory and bends the evil will into good.”

I have translated for you into our modern language:“If you are whipped, you will immediately want to study, your memory will return and you won’t even think about not doing your homework.”

Anyone who doesn’t listen to the teacher will be forced to kneel on a pea bed in the corner. Or they will leave you without lunch.

Those who learned their lessons went home, and it was time for us to return from our journey.

Guys, you are convinced that education has come a long way and, having reached you, has undergone many changes. Learning has become more interesting, learning has become accessible to everyone.

You are students. And school today- your main job.You could say it's yours profession.

To master a profession, you need to master many secrets, show diligence, develop willpower and perseverance.

Your school grade is the result of your work. If you don’t understand something, if something doesn’t work out for you, you should make an effort and achieve your goal. And we, your teachers and parents, will help you with this. Every parent wants to see their child educated. We can say that educating your child is one of the values of family education.

I wish you all success in the new academic year, effort and diligence. May every day at school bring you joy. I wish my parents patience and prudence. Remember that a student’s work is no less important and complex than yours. Be tolerant and attentive to your children. And most importantly, be their helpers.

Reflection

Every year, schoolchildren sit down at their desks to once again “gnaw on the granite of science.” This has been going on for over a thousand years. The first schools in Rus' were radically different from modern ones: before there were no directors, no grades, or even division into subjects. the site found out how education was conducted in schools of past centuries.

Lessons from the breadwinner

The first mention of the school in ancient chronicles dates back to 988, when the Baptism of Rus' took place. In the 10th century, children were taught mainly at the priest’s home, and the Psalter and Book of Hours served as textbooks. Only boys were accepted into schools - it was believed that women should not learn to read and write, but do household chores. Over time, the learning process evolved. By the 11th century, children were taught reading, writing, counting and choral singing. “Schools of book learning” appeared - original ancient Russian gymnasiums, the graduates of which entered the public service: as scribes and translators.At the same time, the first girls' schools were born - however, only girls from noble families were accepted to study. Most often, the children of feudal lords and rich people studied at home. Their teacher was a boyar - the “breadwinner” - who taught schoolchildren not only literacy, but also several foreign languages, as well as the basics of government.

Children were taught literacy and numeracy. Photo: Painting by N. Bogdanov-Belsky “Oral Abacus”

Little information has been preserved about ancient Russian schools. It is known that training was carried out only in large cities, and with the invasion of Rus' by the Mongol-Tatars, it stopped altogether for several centuries and was revived only in the 16th century. Now schools were called “schools”, and only a representative of the church could become a teacher. Before starting a job, the teacher had to pass a knowledge exam himself, and the potential teacher’s acquaintances were asked about his behavior: cruel and aggressive people were not hired.

No ratings

The schoolchildren's day was completely different from what it is now. There was no division into subjects at all: students received new knowledge in one general flow. The concept of recess was also absent - during the whole day the children could only take one break, for lunch. At school, the children were met by one teacher, who taught everything at once - there was no need for directors and head teachers. The teacher did not grade the students. The system was much simpler: if a child learned and told the previous lesson, he received praise, and if he did not know anything, he was punished with rods.Not everyone was accepted into the school, but only the smartest and most savvy children. The children spent the whole day in classes from morning until evening. Education in Rus' proceeded slowly. Now all first-graders can read, but previously, in the first year, schoolchildren learned the full names of letters - “az”, “buki”, “vedi”. Second graders could form intricate letters into syllables, and it was only in the third year that children could read. The main book for schoolchildren was the primer, first published in 1574 by Ivan Fedorov. Having mastered letters and words, the children read passages from the Bible. By the 17th century, new subjects appeared - rhetoric, grammar, land surveying - a symbiosis of geometry and geography - as well as the basics of astronomy and poetic art. The first lesson on the schedule necessarily began with general prayer. Another difference from the modern education system was that children did not carry textbooks with them: all the necessary books were kept at school.

Available to everyone

After the reform of Peter I, a lot has changed in schools. Education acquired a secular character: theology was now taught exclusively in diocesan schools. By decree of the emperor, so-called numerical schools were opened in the cities - they taught only literacy and basic arithmetic. Children of soldiers and lower ranks attended such schools. By the 18th century, education became more accessible: public schools appeared, which even serfs were allowed to attend. True, forced people could study only if the landowner decided to pay for their education.

Previously, schools did not have divisions into subjects. Photo: Painting by A. Morozov “Rural Free School”

It was not until the 19th century that primary education became free for everyone. Peasants went to parish schools, where education lasted only one year: it was believed that this was quite enough for serfs. Children of merchants and artisans attended district schools for three years, and gymnasiums were created for nobles. The peasants were taught only literacy and numeracy. In addition to all this, the townspeople, artisans and merchants were taught history, geography, geometry and astronomy, and the nobles were prepared in schools to enter universities. Women's schools began to open, the program in which was designed for 3 years or 6 years - to choose from. Education became publicly accessible after the adoption of the corresponding law in 1908. Now the school education system continues to develop: in September, children sit down at their desks and discover a whole world of new knowledge - interesting and immense.

How to find out the schedule of the exam, oge and gve

How to find out the schedule of the exam, oge and gve Criteria for evaluating the entire OGE

Criteria for evaluating the entire OGE Option Kim Unified State Exam Russian language

Option Kim Unified State Exam Russian language Formation of the correct sound pronunciation of hissing sounds in preschoolers at home Setting the sound u lesson notes

Formation of the correct sound pronunciation of hissing sounds in preschoolers at home Setting the sound u lesson notes Staging the sound sch, articulation of the sound sch Lesson on setting the sound sch

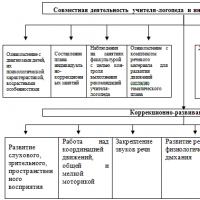

Staging the sound sch, articulation of the sound sch Lesson on setting the sound sch Interaction between a speech therapist and a teacher

Interaction between a speech therapist and a teacher A child confuses paired consonants in writing

A child confuses paired consonants in writing