When Khrushchev's year was lifted. Khrushchev's resignation. Years of rule, reasons for the resignation of Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev. Leader in isolation

Reforms carried out from above were inconsistent and contradictory. They met misunderstanding and resistance from the party-state apparatus. These phenomena together paved the way for Khrushchev’s removal from the leadership of the party and the country and the partial restoration of Stalinist orders.

Factors that directly contributed to the success of the October 1964 coup include:

1. Khrushchev lost the support of almost all social strata of Soviet society.

a) Workers were outraged by the increase in meat and butter prices in 1962 and the shortage of goods, which led to the tragic events of Novocherkassk.

b) The peasantry and state farm workers were extremely dissatisfied with the strict restrictions on personal subsidiary plots, the undermining of the collective farm economy as a result of high costs for the accelerated purchase of MTS equipment, the line to eliminate clean fallows and crops of perennial grasses, and the shortage of manufactured goods.

c) The intelligentsia protested the renewed persecution of prominent writers and artists, the advantages in entering universities for young production workers and, in connection with this, the decrease in the level of training of specialists, as well as the use of people of intellectual labor in physical work.

d) Dosed liberalization caused indignation among orthodox conservatives.

e) Party officials were unhappy Firstly, the division of party organizations into industrial and rural in 1962, since, in their opinion, this gave rise to confusion and confusion, weakened the ties between industry and agriculture, and could also lead to the formation of a peasant party of the Socialist Revolutionary type. Secondly, the party bureaucracy was posed by a serious threat to the norms of systematic renewal of all party bodies introduced in 1961 at the XXII Congress of the CPSU. Third, the nomenclature was irritated by frequent and harsh attacks on party officials.

f) Leaders of industrial and agricultural enterprises opposed administrative dictates and endless reorganizations.

g) The career military could not forgive Khrushchev for the removal from the post of Minister of Defense G.K. Zhukov, the sharp reduction of the army without creating the necessary living facilities for officers being transferred to the reserve.

3) dissidents for the most part at that time were not oriented toward capitalism and, for the most part, did not question the communist perspective.

2. The masses were not spiritually and psychologically ready for radical changes in the socio-political, economic and ideological spheres.

Due to the failures of Khrushchev's reforms, many workers have an increased desire to return to the harsh orders of the Stalinist period. The lack of democratic traditions among the masses and the conformism cultivated by decades of Stalinist tyranny had an effect.

3. The main reformer himself - Khrushchev - despite all the progressiveness of many of his steps, was a son of the Stalin era and could not immediately discard its prejudices, and partly its methods and approaches to business. Hence the half-heartedness, inconsistency, zigzags and fluctuations. In addition, he lacked theoretical training and general culture. He relied primarily on the reorganization of administrative management structures, on preserving intact existing forms of ownership, the existing economic mechanism and socio-political system.

4. Over time, the people as a whole began to be irritated by the praise of Khrushchev, broadcast declarations about the imminent advent of communism, calls in the coming years to catch up with the United States in the production of milk, meat, and butter per capita, especially since all this was in the late 50s years came into conflict with the general deterioration of the economic situation.

All these factors led to the failure of Khrushchev's reforms and the resignation of Khrushchev himself.

Conclusion.

In 1964, the policy of reforms carried out by N.S. ended. Khrushchev. The transformations of this period were the first and most significant attempt to reform Soviet society. The desire of the country's leadership to overcome the Stalinist legacy and renew political and social structures was only partially successful. The reforms initiated from above did not bring the expected effect. The deterioration of the economic situation caused dissatisfaction with the reform policy and its initiator N.S. Khrushchev. The democratization of socio-political and cultural life, announced by the “collective leadership” of the country, turned into its temporary liberalization.

On October 14, 1964, a new era began in the history of the USSR. The plenum of the CPSU Central Committee dismissed the First Secretary of the Communist Party Nikita Khrushchev from his post. The last “palace coup” in Soviet history took place, making Leonid Brezhnev the new leader of the party.

It was officially announced that Khrushchev was resigning due to health conditions and old age. Soviet citizens were notified of this resignation by a laconic message in the newspapers. Khrushchev simply disappeared from public life: he stopped appearing in public, appearing on TV screens, on radio broadcasts and on newspaper editorials. They tried not to mention him, as if he never existed. Only much later did it become known that Khrushchev was removed thanks to a well-thought-out conspiracy in which almost the entire nomenklatura elite was involved. The first secretary was displaced by those people whom he himself had once elevated and brought closer to himself. Life found out the circumstances of the revolt of the “loyal Khrushchevites.”

Although Nikita Khrushchev always played the role of a rural simpleton, showing with all his appearance that he should not be taken seriously, in reality he was not so simple at all. He survived the years of Stalin's repressions, while occupying fairly high positions. After Stalin's death, he, along with his comrades in the leader's inner circle, cooperated against Beria. Then he managed to defeat another political heavyweight - Malenkov, who was first among equals in the post-Stalin USSR.

Finally, in 1957, when Stalin's old guard united against Khrushchev, he achieved the almost incredible. He managed to retain power, repelling the attack of such heavyweights as Voroshilov, Molotov, Kaganovich, Bulganin and Malenkov.

Both times, the Soviet nomenklatura helped Khrushchev a lot. He bet on it back in 1953 and was right. These people did not at all want a return to Stalin's times, when issues of life and death were determined, in some way, by blind lot. And Khrushchev was able to convince them to support him, giving a guarantee that there would be no return to the old ways and that he would not offend any of the high ranks.

Khrushchev well understood all the subtleties of power intrigues. He elevated those who would be loyal to him and were grateful to him for their career growth, and got rid of those to whom he himself was indebted. For example, Marshal Zhukov, who played a huge role both in the overthrow of Beria in 1953 and in the defeat of the Stalinist guard in 1957, was promptly dismissed from all posts and sent into retirement. Khrushchev had nothing personal with Zhukov, he was simply his debtor, and no leader likes to remain a debtor to anyone.

Khrushchev skillfully selected his entourage, elevating those who had previously occupied leadership positions of the second or third order. By the beginning of the 60s, in the ranks of the highest party nomenklatura there were only three people who did not owe their nomination to Khrushchev and were very major figures in their own right. These are Alexey Kosygin, Mikhail Suslov and Anastas Mikoyan.

Even in Stalin's time, Kosygin repeatedly held various People's Commissar and ministerial positions, headed the RSFSR, and in addition, was deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, that is, deputy of Stalin himself.

As for Suslov, he always sought to remain in the shadows. Nevertheless, the positions he held indicate that he was a very influential person already under Stalin. He was not only the secretary of the Central Committee, but also led party propaganda, as well as international party relations.

As for Mikoyan, in a competition for the most “unsinkable” politicians, he would have won the first prize by a huge margin. To sit in leadership positions throughout all the turbulent eras “from Ilyich to Ilyich” is a great talent. Looking ahead: Mikoyan was the only one who opposed Khrushchev’s removal.

All the rest moved to the leading roles already under Khrushchev. Under Stalin, they were part of the nomenklatura elite, but of the second or third rank (Shelepin, for example, was the head of the Komsomol). This situation was supposed to guarantee Khrushchev’s rule without any worries or worries for his seat. He hand-picked all the people, so why would they rebel against him? However, in the end it turned out that it was his proteges who played a big role in Khrushchev’s overthrow.

Reasons for the conspiracy

At first glance, the reasons for Khrushchev’s removal are not at all obvious. It seems that the nomenklatura lived with him and did not bother. No black craters at night or interrogations in basements. All privileges are retained. The boss, of course, is eccentric, but on the whole he says the right things - about the need to return to the Leninist precepts of collective governance of the country. Under Stalin there was a great leader and a party with which you could do anything you wanted. A member of the Politburo could easily be declared an English or German spy and shot. And now collective leadership. Although Khrushchev pulls the blanket over himself, everyone has their own weaknesses, in the end, he does not bury himself.

But that was only the case for the time being. Since the late 50s, when Khrushchev finally got rid of all visible competitors and switched to sole rule, he gradually began to forget what he himself had promoted a few years ago. In words, the collective rule of the country was preserved, but in reality, the first secretary made key decisions single-handedly or persistently pushed them through, without listening to objections. This began to cause strong discontent in the highest ranks of the nomenklatura.

This circumstance in itself did not cause Khrushchev’s removal, although it did contribute. Khrushchev was full of ideas; as soon as it dawned on him, he immediately demanded the implementation of this idea, regardless of real possibilities. At the same time, he blamed failures, which happened quite often, on his subordinates, while he attributed successes to himself. This also offended high party officials. Over the course of a decade, they managed to forget Stalin’s times, and Khrushchev, who had previously seemed to them a savior, was now beginning to irritate him with his fussiness and rude manner of communication. If earlier high ranks lived with a vague premonition of the doorbell ringing at night, now with a premonition of a thrashing from the first secretary for another failure, which is inevitable, because the reform is not at all thought out, but Khrushchev demands its implementation at all costs.

The main mistake of the Secretary General was the administrative reform he initiated, which hit the positions of the party nomenklatura. At one time, Malenkov had already made an unforgivable mistake, which cost him power: he began to cut the benefits of party officials, relying on the state apparatus. In this situation, it was a matter of technique for Khrushchev to make a fuss and win over the nomenklatura to his side. But now he himself made a mistake.

The introduction of national economic councils caused great dissatisfaction. The economic councils essentially took over the management of industry enterprises locally. Khrushchev hoped with this reform to rid production of unnecessary bureaucratic obstacles, but only alienated the highest nomenklatura, which lost part of its influence, while the rank of regional apparatchiks in the economic councils approached almost ministerial.

In addition, the reforms also affected the organization of the party itself. District committees were generally abolished, and regional committees were divided into production and agricultural, which were each responsible for the state of affairs in their own area. Both reforms caused real tectonic shifts; party officials constantly moved from place to place, or even lost their posts. Everyone again remembered what the fear of losing a “warm” workplace is.

Both reforms, especially the party one, caused quiet but furious indignation among the nomenklatura. She didn't feel safe again. Khrushchev swore that he would not harm, but he deceived. From that moment on, the first secretary could no longer count on the support of these layers. The nomenklatura gave birth to him, and the nomenklatura will kill him.

Conspirators

Almost all the highest party and government officials united against Khrushchev. Everyone had their own motives for this. Some have personal ones, others joined for the company so as not to be a black sheep. But all were united by the fact that they began to see in the first secretary a threat to their well-being, or an obstacle to their career.

Brezhnev

Khrushchev and Brezhnev knew each other well from the time they worked in the Ukrainian SSR. After Stalin's death, Khrushchev did not forget his old acquaintance and did a lot for his rise. At the turn of the 50s and 60s, Leonid Brezhnev was one of Khrushchev’s most trusted people. It was he who was entrusted by Khrushchev to oversee one of the most important image projects - the development of virgin lands. About its importance, it is enough to say that a significant part of the Soviet leadership was opposed to this project and its failure could have cost Khrushchev very dearly.

It was Khrushchev who introduced him to the secretariat and Presidium of the Central Committee, and later made him chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. In July 1964, Khrushchev decided to remove Brezhnev from the post of chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council. Even from the transcript of the meeting, one can feel that this caused very strong dissatisfaction with Brezhnev, who liked to travel to foreign countries in the role of the informal “president” of the state. Khrushchev was cheerful at the meeting and literally burst out with jokes and jokes, while Brezhnev spoke extremely laconically and monosyllabically.

Kosygin

Alexey Kosygin was one of the few people who could look down on Khrushchev, since he made his career under Stalin. Unlike most Soviet high-ranking leaders, Kosygin made a career not along the party line, but along the lines of cooperation and industry, that is, he was more of a technocrat.

There was no reason to remove him, and there was no need, since he really understood Soviet industry. I had to endure it. At the same time, it was no secret that Kosygin and Khrushchev had a rather cool attitude towards each other. Khrushchev did not like him for his “old views,” and Kosygin did not like the first secretary for his amateurish approach to serious problems. Kosygin joined the conspiracy without much hesitation.

Suslov

Mikhail Suslov was an influential ideologist already during the time of Stalin. For Khrushchev - and subsequently Brezhnev - he was an irreplaceable person. He had a huge card index where he kept exclusively quotes from Lenin’s works for all occasions. And Comrade Suslov could present absolutely any decision of the party as “Leninist” and significantly strengthen his authority, since no one in the USSR allowed themselves to challenge Lenin.

Since Khrushchev had almost no education and did not even really know how to write, he could not, like Lenin or Stalin, act as a party theorist. This role was taken on by Suslov, who found ideological justification for all the reforms of the First Secretary.

Suslov had no personal complaints against Khrushchev, but joined the conspiracy, sensing the power behind it. Moreover, he played a very active role in it. It was Suslov who was entrusted with the ideological justification of the reasons for Khrushchev’s removal from office.

"Komsomol members"

Members of the "Shelepintsy" group. They are "Komsomol members". Its most prominent representatives were Alexander Shelepin and Vladimir Semichastny. The leader in this tandem was the first. In the last year of Stalin's life, Shelepin headed the Soviet Komsomol. There he became close to Semichastny, who became his confidant. When Shelepin left the Komsomol, he patronized a comrade, who replaced him in this position. Later the same thing happened with the KGB.

Shelepin owed a lot to Khrushchev. The position of the commander-in-chief of the Komsomol, although it was prominent, was still far from first-rank. And Khrushchev appointed Shelepin to lead the powerful KGB with a clear task: to firmly subordinate the party structure. And in the last years of Khrushchev’s rule, Shelepin rose to the position of Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, that is, Khrushchev himself.

At the same time, Shelepin, along with Semichastny, played one of the key roles in the removal of his patron. Largely due to the fact that the displacement opened up great prospects for him. In fact, Shelepin was the most powerful among the conspirators. He tightly controlled the KGB, in addition, he had his own secret party group of “Komsomol members”, which included his former associates in the Komsomol. Khrushchev's removal opened the path to power for him.

Podgorny

Former head of the Ukrainian SSR. He knew Nikita Sergeevich from his work in the Ukrainian SSR and was considered a loyal Khrushchevite. At one time, Podgorny played a significant role in resolving the issue of Stalin’s reburial, but after Khrushchev’s administrative reform he sharply lost interest in him. In addition, in 1963, the latter subjected him to severe criticism for the poor harvest in the Ukrainian SSR and removed him from his post. Nevertheless, in order not to offend his old comrade, he transferred him to Moscow and found a place in the Secretariat of the Central Committee.

Nikolai Podgorny played an important symbolic role in the conspiracy. He had to ensure the participation of the Ukrainian higher nomenklatura in it, which would have been a particularly strong blow for Khrushchev, because he considered Ukraine his patrimony and always closely watched it, even becoming first secretary.

In exchange for participation in the conspiracy, Podgorny was promised the position of chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council.

Malinovsky

Minister of Defense. It cannot be said that he owed his career to Khrushchev, since he became a marshal under Stalin. Nevertheless, he did a lot for him. At one time, after the disastrous Kharkov operation, Stalin was thinking of taking drastic measures against Malinovsky, but he was defended by Khrushchev, who was a member of the front’s military council. Thanks to his intercession, Malinovsky escaped with only a demotion: from front commander he became army commander.

In 1957, after the removal of the dangerous Zhukov, Khrushchev appointed an old acquaintance as Minister of Defense. However, all this did not prevent Rodion Malinovsky from joining the conspiracy without much hesitation. However, his role was not so great: he was only required to ensure the neutrality of the army, that is, to exclude Khrushchev’s attempts to use this resource to counter the conspirators.

Ignatov

Nikolai Ignatov was one of the few people to whom Khrushchev was indebted, and not they to him. Three months before Stalin’s death, he joined the Secretariat of the Central Committee and the Soviet government, taking the post of Minister of Procurement, but immediately after the death of the leader he lost all posts and held leadership positions in provincial regional committees.

Ignatov played a big role in saving Khrushchev in 1957. He was one of the members of the Central Committee who broke into the meeting of the Presidium and demanded the convening of the Plenum of the Central Committee, thanks to which they managed to seize the initiative from the hands of Molotov, Malenkov and Kaganovich. At the Plenum, the majority was for Khrushchev, which allowed him to remain in power, and the “anti-party group” of conspirators was deprived of all posts and expelled from the CPSU.

In gratitude, Khrushchev made Ignatov chairman of the Presidium of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet and his deputy in the Council of Ministers. Nevertheless, Ignatov became an active participant in the conspiracy - largely due to his ambition, penchant for intrigue and behind-the-scenes maneuvers.

Khrushchev's removal

The plan to overthrow the first secretary was born during a hunt. It was there that the key core of the conspirators reached agreement on the need to remove Khrushchev and intensify work with the nomenklatura.

Already in September 1964, the core of the conspirators was formed. Virtually all the key party officials joined the conspiracy. Under these conditions, winning over the rest of the nomenclature to one’s side in case of the need to convene a Plenum was already a matter of technique.

The plan was simple. At a special meeting, the Presidium of the Central Committee subjected Khrushchev to severe criticism and demanded his resignation. If he did not agree, a Plenum of the Central Committee was convened, at which Khrushchev was again subjected to harsh criticism and his resignation was demanded. This scenario completely repeated the events of 1957, when the so-called anti-party group from among the Stalinist guard secured the support of the majority of members of the Presidium, but the Plenum that time defended Khrushchev. Appropriate preparations have now been made to ensure that the Plenum does not do this. In case Khrushchev began to resist and refused to leave, a report should have been read out with damning criticism of the shortcomings of his rule.

In addition to sharp criticism of Khrushchev’s personal shortcomings (he began to drift towards the cult of personality, pulls the blanket over himself, is extremely rude to his subordinates), he also contained criticism of Khrushchev’s policies (declining economic growth rates, worsening the situation in industry and agriculture). Many complaints were made against Khrushchev, even to the point that he advocated the construction of five-story buildings instead of large high-rise buildings, which led to a decrease in the density of buildings in cities and an “increase in the cost of communications.”

At the very end of the report, a huge part of it was devoted to the reorganization of the party, because the standard of living of workers and agricultural issues are, of course, interesting, but undermining the party is sacred. This is something that every nomenklatura literally felt and couldn’t come to terms with. Heavy artillery, after which there could no longer be anyone who disagreed with Khrushchev’s removal. It was explained in detail why the reorganization of the party grossly contradicts Lenin’s principles and causes dissatisfaction among all party officials (“people cannot now work normally, they live, so to speak, under the fear of new reorganizations”).

However, the plot almost failed. In September, Khrushchev received information about the suspicious intentions of the members of the Presidium from the chief of security of one of the conspirators, Nikolai Ignatov. However, Khrushchev was surprisingly indifferent to this fact and quite calmly went to Abkhazia on vacation. He just asked Mikoyan to meet with him and check the information. Mikoyan complied with his boss’s request, however, without developing vigorous activity. Soon he also went on vacation.

The conspirators took advantage of the absence of the leader and worked out the final issues at a closed meeting of the Presidium. In fact, they controlled all the levers. The KGB and the army were subordinate to them, even Khrushchev’s fiefdom - Ukraine - too. Both the previous first secretary of the local Communist Party, Podgorny, and the current one, Shelest, supported the conspirators. Khrushchev simply had no one to rely on.

Now it was necessary to summon Khrushchev to Moscow under the pretext of urgent participation in a meeting of the Presidium. Shelest recalled: “We decided that Brezhnev would call. And we were all present when Brezhnev talked with Khrushchev. It was scary. Brezhnev trembled, stuttered, his lips turned blue.” Shelepin also testified that Brezhnev was “cowardly to call” for a long time. However, it is worth noting that both were later offended by Brezhnev and could embellish the facts in their memoirs.

A closed meeting of the Presidium took place on October 12. And on the 13th Khrushchev was supposed to fly in from Pitsunda. Nikita Sergeevich, who arrived in Moscow, could not help but be alarmed by the fact that no one from the Presidium came to meet him, only the KGB chief Semichastny.

After the arrival of the first secretary, all members of the Presidium unanimously harshly criticized both his personal qualities and political mistakes and failures. The most important thing is that all this happened in accordance with the ideological guidelines of Khrushchev himself. Three months before these events, in July 1964, when he removed Brezhnev from his post, Khrushchev said: “We don’t need to tighten the screws now, but we need to show the strength of socialist democracy. With democracy, of course, anything can happen. Once democracy, then the leadership can be criticized. And this must be understood. Without criticism there is no democracy. Then once he said it, it means he is an enemy of the people, drag him to jail with or without trial. We have moved away from this, we have condemned this. Therefore, so that it is more democratically, it is necessary to remove obstacles: release one and promote the other."

It was in accordance with this statement that the conspirators acted. They say, what a conspiracy, we have a socialist democracy, as you yourself wanted, Comrade First Secretary. You yourself said that without criticism there is no democracy and even the leadership can be criticized.

The conspirators beat Khrushchev with his own weapons, accusing him of a cult of personality and violation of Leninist principles. These were precisely the accusations that Khrushchev once brought against Stalin.

The first secretary listened to criticism addressed to him all day. He didn't really try to object. He admitted rudeness with his subordinates and lack of restraint in words, as well as some mistakes. Perhaps he only tried to challenge the party reform with the division of regional committees and the abolition of district committees, realizing that this was apparently the main reason for the uprising of the nomenklatura.

The next day, October 14, the meeting of the Presidium continued, since everyone could not meet on one day. None of the former “loyal Khrushchevites” came out in support of their boss. Everyone smashed him to smithereens. Only Mikoyan was on Khrushchev’s side, who was one of the few who owed him nothing at all. The cunning Mikoyan also joined in criticizing the boss, but at the end he made a reservation that he considered it necessary to leave Khrushchev in the party leadership, but at the same time deprive him of part of his powers and the post of chairman of the Council of Ministers.

Finally, Khrushchev made the last word. He correctly assessed the situation and did not fight to the end. He was no longer young, he had turned 70, and he did not strive to retain power at any cost. In addition, he was experienced in hardware intrigues and understood perfectly well that this time he had been caught, having seized all the levers, and he would not be able to do anything. And if he is stubborn, he will make things worse for himself. Oh well, they’ll still put you under arrest.

In his last word, Khrushchev said: “I don’t ask for mercy - the issue is resolved. I told Comrade Mikoyan: “I won’t fight, the basis is one.” Why will I look for paint and smear you? And I rejoice: finally the party has grown and can control any person. We gathered and "You smear Mr..nom, but I can’t object. I felt that I couldn’t cope, but life was tenacious, it gave rise to arrogance. I express my agreement with the proposal to write a statement asking for release."

That same evening, an extraordinary Plenum of the Central Committee opened, at which Khrushchev’s resignation was agreed upon. "Due to health conditions and reaching old age." Since Khrushchev did not resist, it was decided not to voice the devastating report at the Plenum. Instead, Suslov made a softer speech.

At the same Plenum, the division of the posts of first secretary and chairman of the Council of Ministers was approved. The party was headed by Brezhnev, and Kosygin became the head of the government.

Khrushchev retained his dacha, apartment, personal car and access to the Kremlin canteen. He didn't ask for more. For him, big politics is over. But for the winners it was all just beginning. Brezhnev was seen by many as a temporary and compromise figure. He was not very well known to the general public, and besides, he gave the deceptive impression of a good-natured softie, inexperienced in intrigue. Shelepin, who retained the post of Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers and relied on his “Komsomol members,” had great ambitions. The former leader of the Ukrainian SSR Podgorny, who was not averse to repeating the path of Khrushchev, also had far-reaching plans. Kosygin strengthened his influence and pursued an independent line. All of them faced a struggle for influence. But that is another story.

At the October (1964) Plenum of the CPSU Central Committee N.S. Khrushchev was removed for voluntarism and “for health reasons.” Voluntarism was understood as the replacement of thoughtful collective decisions with the setting of tasks advocated by Khrushchev alone, which were implemented exclusively by administrative pressure and were often deliberately doomed to failure.

Occupying two posts - first secretary of the Central Committee and chairman of the government - Khrushchev tried to place people loyal to himself in key positions in the state. But his spontaneous, often ill-considered actions in domestic and foreign policy irritated both the apparatus and ordinary citizens. People were tired of constant innovations that often canceled or replaced the decisions they had just made. New initiatives in the reorganization of management, the structure of ministries and departments, agriculture, etc. were also perceived with fear. Some price increases due to the denomination of the ruble caused a muted murmur among the people. Collective farmers could not rejoice at the reduction of their plots. His actions in foreign policy were perceived ambiguously; diplomats believed that Khrushchev’s behavior could complicate the international position of the Soviet Union. The top military leadership condemned the first secretary of the Central Committee for the sharp reduction of the army. The creative intelligentsia considered Khrushchev's measures to democratize cultural life to be completely insufficient, while in scientific circles they recalled the threat of the country's leader to disperse the Academy of Sciences if it did not accept Lysenko's supporters into its composition. Dissatisfaction with Khrushchev also grew in the regions, whose leadership wanted a more predictable supreme leader of the country. Finally, people did not like the fact that in place of the cult of one person, the cult of another, who was once subordinate to the first, began to appear. The film “Dear Nikita Sergeevich” appeared on the screens of the country.

FROM ALL POSTS

In the spring and summer of 1964, secret negotiations began among members of the Soviet leadership with the goal of eliminating Khrushchev. The team advocating the removal of the leader was led by L.I. Brezhnev, M.A. Suslov, A.N. Shelepin, N.V. Podgorny, V.E. Semichastny and others. With Khrushchev’s departure for vacation in Pitsunda, secret consultations intensified. From the south, Khrushchev was summoned by telephone to a meeting of the Presidium of the Central Committee, ostensibly to discuss agrarian issues. On October 12-13, 1964, the Presidium of the Central Committee demanded Khrushchev’s resignation. Suslov made a report against the first secretary. Khrushchev signed a statement renouncing all posts, which was approved on October 14. Khrushchev was removed from all posts and his political career ended with the title of “pensioner of union significance.” He moved to a dacha in the village of Petrovo-Dalneye near Moscow, where he sometimes worked on the site and dictated his memoirs onto a tape recorder. Khrushchev died seven years after his resignation on September 11, 1971.

L.I. was elected first secretary of the party's Central Committee. Brezhnev, Chairman of the Council of Ministers - A.N. Kosygin. A.I. remained Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR until the end of 1965. Mikoyan, but then he was replaced by N.V. Podgorny. Brezhnev's rise to power meant the end of Khrushchev's innovations.

UNPREDICTABLE - DANGEROUS

The USSR under Khrushchev: some personal impressions of the former British ambassador in Moscow Sir F. Roberts, stated in a conversation with members of the Great Britain-USSR Association in May 1986 (F. Roberts’ words reflect, of course, the point of view of a Western diplomat who looked at the USSR as enemy during the Cold War).

“Khrushchev was a very sociable person, he loved to organize receptions, attend them, and was always ready to devote time to us, Western ambassadors. During a large reception in the Kremlin, I was told that he had just made an insulting speech about Great Britain, and I was determined to treat him very coldly. But he came straight to me and told me not to be angry with him, that it was in his nature to flare up like that, and continued to demonstrate our friendly relations in public...

The Soviet people never trusted Khrushchev enough. He returned many millions from Stalin's concentration camps, largely eliminated the threat of arbitrary arrests, and improved the living conditions of the Soviet people. He presided over the Soviet Union's great achievements in space exploration, beginning with Sputnik and Gagarin's flight, which, at least temporarily, allowed the Russians to leapfrog the Americans and gave him hope that the Soviet Union could catch up with the United States in other areas. He also transformed the Soviet Union into a world power with a major role in the Third World. Unlike Stalin, he enjoyed visiting countries such as India, Indonesia and Egypt, as well as the United States and Western European countries. Without claiming, like Stalin, theoretical superiority over Lenin, he understood the consequences of the emergence of nuclear power and abandoned the old dogma about the inevitability of war with capitalist countries in favor of “peaceful coexistence.”

Unfortunately, this conviction did not prevent him from embarking on such provocative and risky undertakings as an attempt to change the status of Berlin, as well as the Cuban missile crisis... His agricultural policy, which was based on grain production and the development of virgin lands in Kazakhstan, also was not successful. As a result of all this, Khrushchev’s associates got rid of such an unpredictable and therefore dangerous leader in 1964...

[Khrushchev] lacked Stalin's toughness and basic prudence. All his efforts aimed at improving the lives of Soviet people did not win their universal respect. He had to back down too often after risky undertakings, and, usually, skillful management of them was not enough to reassure his colleagues ... "

WHO DID YOU REPLACE?

“Unlike Stalin or Khrushchev, Brezhnev did not have bright personal characteristics. It is difficult to call him a major political figure. He was a man of the apparatus and, in essence, a servant of the apparatus.

...In everyday terms, he was a kind person, in my opinion. In politics - hardly... He lacked education, culture, intelligence in general. In Turgenev’s times he would have been a good landowner with a large hospitable house...”

Journalist, employee of the apparatus of the CPSU Central Committee in 1963-1972. A.E. Bovin about L.I. Brezhnev

“Of course, now a question may arise: if it was clear that decisions were being made that did not meet the interests of the country, then why did the Politburo and the Central Committee not make other decisions that would actually meet the interests of the state and the people?

It must be taken into account that there was a certain decision-making mechanism. I can provide facts to support this thesis. Not only me, but also some other members of the Politburo rightly pointed out that heavy industry and giant construction projects absorb colossal funds, and industries producing consumer goods - food, clothing, shoes, etc., as well as services - are in paddock

Isn't it time to make adjustments to our plans? - we asked.

Brezhnev was against it. The plans remained unchanged. The disproportion of these plans affected the situation until the end of the 80s... Or take, for example, the personal farm of a collective farmer. In fact, it was destroyed. The peasants could not feed themselves...

I did not have to observe that Brezhnev was deeply aware of the shortcomings and serious failures in the country's economy. ...He was not fully aware of this. I took on faith the statements of employees who were directly responsible for one direction or another...”

Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR in 1957-1985. A.A. Gromyko about L.I. Brezhnev

The post-war political period was characterized by stability. Until 1991, anything changed very rarely. The people soon got used to the emerging state of affairs, its best representatives joyfully carried portraits of the new leaders across Red Square during the May and November demonstrations, and those who were also good, but worse, simultaneously did the same with them in other cities, regional centers, and villages and villages. Overthrown or deceased party and state leaders (except Lenin) were forgotten almost instantly, even jokes were stopped being written about them. Outstanding theoretical works were no longer studied in schools, technical schools and institutes - their place was taken by books by new secretaries general, with approximately the same content. Some exception was a politician who overthrew the authority of Stalin in order to take his place in the minds and souls.

Unique case

He truly became an exception among all party leaders not only before, but also after himself. Khrushchev’s bloodless and quiet resignation, without a solemn funeral or revelations, took place almost instantly and looked like a well-prepared conspiracy. In a sense, it was like that, but, by the standards of the CPSU Charter, all moral and ethical standards were observed. Everything happened quite democratically, albeit with a completely justified admixture of centralism. An extraordinary plenum met, discussed the behavior of his comrade, condemned some of his shortcomings and came to the conclusion that it was necessary to replace him in a leadership position. As they wrote in the protocols then, “they listened and decided.” Of course, in Soviet realities this case became unique, like the Khrushchev era itself with all the miracles and crimes that happened in it. All previous and subsequent general secretaries were solemnly taken to the Kremlin necropolis - their final resting place - on gun carriages, except for Gorbachev, of course. Firstly, because Mikhail Sergeevich is still alive, and secondly, he left his post not because of a conspiracy, but in connection with the abolition of his position as such. And thirdly, in some ways he and Nikita Sergeevich turned out to be similar. Another unique case, but not about it now.

First try

Khrushchev's resignation, which occurred in October 1964, happened, in a sense, on the second attempt. Almost seven years before this fateful event for the country, three members of the Presidium of the Central Committee, later called an “anti-party group,” namely Kaganovich, Molotov and Malenkov, initiated the process of removing the first secretary from power. If we consider that in fact there were four of them (to get out of the situation, another conspirator, Shepilov, was declared simply to “join”), then everything also happened in accordance with the party charter. We had to use non-standard measures. Members of the Central Committee were urgently transported to Moscow for the plenum from all over the country by military aircraft, using high-speed MiG interceptors (UTI training “sparks”) and bombers. Defense Minister G.K. Zhukov provided invaluable assistance (without her, Khrushchev’s resignation would have taken place back in 1957). The “Stalinist Guards” were neutralized: they were expelled first from the Presidium, then from the Central Committee, and in 1962 they were completely expelled from the CPSU. They could have shot him, but that didn’t work out.

Prerequisites

The removal of Khrushchev in 1964 was a success not only because the action was well prepared, but also because it suited almost everyone. The claims made at the October Plenum, with all their party and lobbying bias, cannot be called unfair. There was a catastrophic failure in almost all strategically important areas of politics and economics. The well-being of the broad working masses was deteriorating, bold experiments in the defense sector led to the half-life of the army and navy, collective farms withered away, becoming “reverse millionaires,” and prestige in the international arena was declining. The reasons for Khrushchev's resignation were numerous, and it itself became inevitable. The people accepted the change of power with quiet glee, redundant officers rubbed their hands gloatingly, artists who received laureate badges in Stalin's times welcomed the manifestation of party democracy. Collective farmers from all climate zones, tired of sowing corn, did not expect miracles from the new Secretary General, but vaguely hoped for the best. In general, after Khrushchev’s resignation, there were no popular unrest.

Achievements of Nikita Sergeevich

In fairness, one cannot fail to mention the bright deeds that the removed first secretary managed to accomplish during the years of his reign.

First, the country held a series of events that marked a departure from the grimly authoritarian practices of the Stalin era. They were generally called a return to Leninist principles of leadership, but in fact they consisted of the demolition of almost all the numerous monuments (except for the one in Gori), permission to print some literature that exposed tyranny, and the separation of the party line from the personal qualities of the character of the person who died in 1953 leader.

Secondly, collective farmers were finally issued passports, formally classifying them as full citizens of the USSR. This by no means meant freedom to choose where to live, but some loopholes still appeared.

Thirdly, in a matter of a decade, a breakthrough was made in housing construction. Millions of square meters were rented out annually, but despite such large-scale achievements, there were still not enough apartments. Cities began to “swell” with former collective farmers coming to them (see previous paragraph). The housing was cramped and uncomfortable, but the Khrushchev buildings seemed to their inhabitants at that time like skyscrapers, symbolizing new, modern trends.

Fourthly, space and space again. All Soviet missiles were the first and best. The flights of Gagarin, Titov, Tereshkova, and before them the dogs Belka, Strelka and Zvezdochka - all this aroused great enthusiasm. In addition, these achievements were directly related to defense capability. they were proud of the country in which they lived, although there were not as many reasons for this as they wanted.

There were other bright pages during the Khrushchev period, but they were not so significant. Millions of political prisoners received freedom, but upon leaving the camps, they soon became convinced that even now it was better to keep their mouths shut. It's more reliable.

Thaw

This phenomenon today evokes only positive associations. It seems to our contemporaries that in those years the country arose from a long winter sleep, like a mighty bear. Streams began to gurgle, whispering words of truth about the horrors of Stalinism and the Gulag camps, the sonorous voices of poets sounded at the monument to Pushkin, the dudes proudly shook their lush hairstyles and began to dance rock and roll. This is roughly the picture portrayed by modern films made on the theme of the fifties and sixties. Alas, things were not quite like that. Even rehabilitated and released political prisoners remained deprived. There was not enough living space for “normal” citizens, that is, those who were not in prison.

And there was one more circumstance, important for its psychological nature. Even those who suffered from Stalin's cruelty often remained his admirers. They could not come to terms with the rudeness shown during the overthrow of their idol. There was a pun about the cult, which of course existed, but also about the personality, which also occurred. The hint was a low assessment of the overthrower and his own guilt in the repressions.

The Stalinists made up a significant part of those dissatisfied with Khrushchev's policies, and they perceived his removal from power as fair retribution.

People's dissatisfaction

In the early sixties, the economic situation began to deteriorate. There were many reasons for this. Crop failures plagued collective farms, which lost many millions of workers who worked on city construction sites and factories. The measures taken in the form of increasing taxes on trees and livestock led to very bad consequences: mass deforestation and “putting under the knife” livestock.

Believers experienced unprecedented and most monstrous persecution after the years of the “Red Terror.” Khrushchev's activities in this direction can be described as barbaric. Repeatedly forced closures of churches and monasteries led to bloodshed.

The “polytechnic” school reform was carried out extremely unsuccessfully and illiterately. It was canceled only in 1966, but the consequences were felt for a long time.

In addition, in 1957, the state stopped paying the bonds that had been forcibly imposed on workers for more than three decades. Today this would be called a default.

There were many reasons for dissatisfaction, including an increase in production standards, accompanied by a decrease in prices coupled with an increase in food prices. And the patience of the people could not stand it: unrest began, the most famous of which were the Novocherkassk events. The workers were shot in the squares, the survivors were caught, tried and sentenced to the same capital punishment. People had a natural question: why did Khrushchev condemn and why was he better?

The next victim is the Armed Forces of the USSR

In the second half of the fifties, the Soviet Army was subjected to a massive, destructive and devastating attack. No, it was not NATO troops or the Americans with their hydrogen bombs who carried it out. The USSR lost 1.3 million troops in a completely peaceful situation. Having gone through the war, become professionals and can do nothing more than serve the Motherland, the soldiers found themselves on the street - they were laid off. The characterization of Khrushchev given by them could become the subject of linguistic research, but censorship would not allow the publication of such a treatise. As for the fleet, this is a completely different matter. All large-tonnage ships that ensure the stability of naval formations, especially battleships, were simply cut into scrap metal. Strategically important bases in China and Finland were mediocrely and uselessly abandoned, and troops left Austria. It is unlikely that external aggression would have brought as much harm as Khrushchev’s “defense” activities. Opponents of this opinion may object that overseas strategists were afraid of our missiles. Alas, they began to be developed under Stalin.

By the way, the First did not spare his savior from the “anti-party clique.” Zhukov was released from his ministerial post, removed from the Presidium of the Central Committee and sent to Odessa to command the district.

“Concentrated in my hands...”

Yes, this very phrase from Lenin’s political testament is quite applicable to a fighter against the Stalinist cult. In 1958, N.S. Khrushchev became chairman of the Council of Ministers; party power alone was no longer enough for him. The methods of leadership, positioned as “Leninist,” actually did not allow the possibility of expressing opinions that did not coincide with the general line. And its source was the mouth of the first secretary. For all his authoritarianism, J.V. Stalin often listened to objections, especially if they came from people who knew their business. Even in the most tragic years, the “tyrant” could change his decision if he was proven wrong. Khrushchev was always the first to express his position and perceived every objection as a personal insult. Moreover, in the best communist traditions, he considered himself a person who understood everything - from technology to art. Everyone knows the incident in Manege, when avant-garde artists became victims of attacks by the “party leader” who went into a rage. Trials were held in the country in the cases of disgraced writers, sculptors were reproached for wasted bronze, which “is not enough for missiles.” By the way, about them. What kind of specialist Khrushchev was in the field of rocket science is eloquently demonstrated by his proposal to V. A. Sudets, the creator of the Dvina (S-75) air defense system, to shove the complex into himself... Well, in general, away. It happened in 1963 in Kubinka, at the training ground.

Khrushchev the diplomat

Everyone knows about how N.S. Khrushchev pounded his shoe on the podium, even today’s schoolchildren have heard at least something about it. No less popular is the phrase about Kuzka’s mother, which caused difficulties among translators, which the Soviet leader was going to show to the entire capitalist world. These two quotes are the most famous, although the direct and open Nikita Sergeevich had a lot of them. But the main thing is not words, but deeds. Despite all the menacing statements, the USSR won few real strategic victories. The adventurous sending of missiles to Cuba was discovered, and a conflict began that almost caused the death of all humanity. The intervention in Hungary caused outrage even among the USSR's allies. Supporting “progressive” regimes in Africa, Latin America and Asia was extremely expensive for the poor Soviet budget and was aimed not at achieving any goals useful for the country, but at causing the greatest harm to Western countries. The initiator of these undertakings was most often Khrushchev himself. A politician differs from a statesman in that he thinks only about short-term interests. This is exactly how Crimea was donated to Ukraine, although at that time no one could have imagined that this decision would entail international consequences.

Coup mechanism

So what was Khrushchev like? A table in two columns, on the right of which his useful deeds would be indicated, and on the left - harmful ones, would distinguish between two traits of his character. Likewise, on the tombstone, created ironically by the reviled Ernst Neizvestny, black and white colors are combined. But this is all rhetoric, but in reality, Khrushchev’s removal occurred primarily due to the party nomenklatura’s dissatisfaction with him. No one asked neither the people, nor the army, nor ordinary members of the CPSU; everything was decided behind the scenes and, of course, in an atmosphere of secrecy.

The head of state rested calmly in Sochi, arrogantly ignoring the warnings he had received about the conspiracy. When he was called to Moscow, he still hoped in vain to rectify the situation. However, there was no support. The State Security Committee, headed by A.N. Shelepin, sided with the conspirators, the army showed complete neutrality (the generals and marshals, obviously, did not forget the reforms and reductions). And there was no one else to count on. Khrushchev's resignation took place in a clerical routine manner and without tragic events.

58-year-old Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, a member of the Presidium, led and carried out this “palace coup”. Undoubtedly, this was a courageous act: in case of failure, the consequences for the participants in the conspiracy could be the most dire. Brezhnev and Khrushchev were friends, but in a special way, in a party way. Nikita Sergeevich’s relationship with Lavrenty Pavlovich was equally warm. And the personal pensioner of union importance treated Stalin very respectfully in his time. In the fall of 1964, the Khrushchev era ended.

Reaction

In the West, at first they were very wary of the change in the main Kremlin occupant. Politicians, prime ministers and presidents have already imagined the ghost of “Uncle Joe” in a semi-military jacket with his invariable pipe. Khrushchev's resignation could mean the re-Stalinization of both the domestic and the USSR. This, however, did not happen. Leonid Ilyich turned out to be a completely friendly leader, a supporter of the peaceful coexistence of the two systems, which, generally speaking, was perceived by orthodox communists as degeneration. The attitude towards Stalin at one time greatly worsened relations with the Chinese comrades. However, even their most critical characterization of Khrushchev as a revisionist did not lead to an armed conflict, while under Brezhnev it did arise (on the Damansky Peninsula). The Czechoslovak events demonstrated a certain continuity in the defense of the gains of socialism and evoked associations with Hungary in 1956, although not completely identical. The war in Afghanistan, which began even later in 1979, confirmed the worst fears about the nature of world communism.

The reasons for Khrushchev's resignation were mainly not the desire to change the vector of development, but the desire of the party elite to maintain and expand their preferences.

The disgraced secretary himself spent the remaining time in sad thoughts, dictating memoirs into a tape recorder in which he tried to justify his actions, and sometimes repenting of them. For him, his removal from office ended relatively well.

By 1964, ten-year reign Nikita Khrushchev led to an amazing result - there were practically no forces left in the country on which the First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee could rely.

He frightened conservative representatives of the “Stalinist guard” by debunking Stalin’s personality cult, and moderate party liberals by his disdain for his comrades-in-arms and the replacement of a collegial leadership style with an authoritarian one.The creative intelligentsia, which initially welcomed Khrushchev, recoiled from him, having heard enough “valuable instructions” and direct insults. The Russian Orthodox Church, accustomed in the post-war period to the relative freedom granted to it by the state, came under pressure it had not seen since the 1920s.

Diplomats were tired of resolving the consequences of Khrushchev’s abrupt steps on the international stage, and the military was outraged by the ill-conceived mass cuts in the army.

The reform of the management system of industry and agriculture led to chaos and a deep economic crisis, aggravated by Khrushchev’s campaign: widespread planting of corn, persecution of collective farmers’ personal plots, etc.

Just a year after Gagarin’s triumphant flight and the proclamation of the task of building communism in 20 years, Khrushchev plunged the country into the Cuban missile crisis in the international arena, and internally, with the help of army units, he suppressed the protest of those dissatisfied with the decline in the living standards of workers in Novocherkassk.

Food prices continued to rise, store shelves became empty, and bread shortages began in some regions. The threat of a new famine looms over the country.

Khrushchev remained popular only in jokes: “On Red Square during the May Day demonstration, a pioneer with flowers comes up to Khrushchev’s Mausoleum and asks:

— Nikita Sergeevich, is it true that you launched not only a satellite, but also agriculture?

-Who told you this? - Khrushchev frowned.

“Tell your dad that I can plant more than just corn!”

Intrigue versus intriguer

Nikita Sergeevich was an experienced master of court intrigue. He skillfully got rid of his comrades in the post-Stalin triumvirate, Malenkov and Beria, and in 1957 managed to resist an attempt to remove him from the “anti-party group of Molotov, Malenkov, Kaganovich and Shepilov, who joined them.” What saved Khrushchev was intervention in the conflict Minister of Defense Georgy Zhukov, whose word turned out to be decisive.

Less than six months had passed before Khrushchev dismissed his savior, fearing the growing influence of the military.

Khrushchev tried to strengthen his power by promoting his own proteges to key positions. However, Khrushchev's management style quickly alienated even those who owed him a lot.In 1963, Khrushchev's ally, Second Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Frol Kozlov, left his post due to health reasons, and his duties were divided between Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Leonid Brezhnev and transferred from Kyiv to work Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Nikolai Podgorny.

From about this moment, Leonid Brezhnev began to conduct secret negotiations with members of the CPSU Central Committee, finding out their moods. Usually such conversations took place in Zavidovo, where Brezhnev loved to hunt.

Active participants in the conspiracy, in addition to Brezhnev, were KGB Chairman Vladimir Semichastny, Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Alexander Shelepin, already mentioned Podgorny. The further it went, the more the circle of participants in the conspiracy expanded. He was joined by a member of the Politburo and the future chief ideologist of the country Mikhail Suslov, Minister of Defense Rodion Malinovsky, 1st Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Alexey Kosygin and others.

Among the conspirators there were several different factions that viewed Brezhnev's leadership as temporary, accepted as a compromise. This, of course, suited Brezhnev, who turned out to be much more far-sighted than his comrades.

“You are planning something against me...”

In the summer of 1964, the conspirators decided to speed up the implementation of their plans. At the July plenum of the CPSU Central Committee, Khrushchev removes Brezhnev from the post of chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, replacing him Anastas Mikoyan. At the same time, Khrushchev rather dismissively informs Brezhnev, who was returned to his previous position - curator of the CPSU Central Committee on issues of the military-industrial complex, that he lacks the skills to hold the position from which he was removed.

In August - September 1964, at meetings of the top Soviet leadership, Khrushchev, dissatisfied with the situation in the country, hinted at an upcoming large-scale rotation in the highest echelons of power.

This forces the last hesitating doubts to be cast aside - the final decision to remove Khrushchev in the near future has already been made.It turns out to be impossible to conceal a conspiracy of this magnitude - at the end of September 1964, through the son of Sergei Khrushchev, evidence of the existence of a group preparing a coup was transmitted.

Oddly enough, Khrushchev does not take active counter actions. The most that the Soviet leader does is threaten the members of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee: “You, friends, are planning something against me. Look, if something happens, I’ll scatter them around like puppies.” In response, members of the Presidium vying with each other begin to assure Khrushchev of their loyalty, which completely satisfies him.

At the beginning of October, Khrushchev went on vacation to Pitsunda, where he was preparing for the plenum of the CPSU Central Committee on agriculture scheduled for November.

As one of the participants in the conspiracy recalled, Member of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee Dmitry Polyansky, on October 11, Khrushchev called him and said that he knew about the intrigues against him, promised to return to the capital in three or four days and show everyone “Kuzka’s mother.”

Brezhnev at that moment was on a working trip abroad, Podgorny was in Moldova. However, after Polyansky’s call, both urgently returned to Moscow.

Leader in isolation

It is difficult to say whether Khrushchev actually planned anything or his threats were empty. Perhaps, knowing about the conspiracy in principle, he did not fully realize its scale.

Be that as it may, the conspirators decided to act without delay.

On October 12, a meeting of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee met in the Kremlin. A decision was made: due to “uncertainties of a fundamental nature that have arisen, to hold the next meeting on October 13 with the participation of Comrade Khrushchev. Instruct tt. Brezhnev, Kosygin, Suslov and Podgorny contact him by phone.” The meeting participants also decided to summon members of the Central Committee and Central Committee of the CPSU to Moscow for a plenum, the time of which would be determined in the presence of Khrushchev.

By this point, both the KGB and the armed forces were effectively controlled by the conspirators. At the state dacha in Pitsunda, Khrushchev was isolated, his negotiations were controlled by the KGB, and ships of the Black Sea Fleet could be seen at sea, arriving “to protect the First Secretary due to the deteriorating situation in Turkey.

By order USSR Defense Minister Rodion Malinovsky, the troops of most districts were put on combat readiness. Only the Kiev Military District, commanded by Peter Koshevoy, the military man closest to Khrushchev, who was even considered as a candidate for the post of Minister of Defense of the USSR.

To avoid excesses, the conspirators deprived Khrushchev of the opportunity to contact Koshev, and also took measures to exclude the possibility of the First Secretary’s plane turning to Kyiv instead of Moscow.

"The last word"

Together with Khrushchev in Pitsunda he was Anastas Mikoyan. On the evening of October 12, the First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee was invited to come to Moscow to the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee to resolve urgent issues, explaining that everyone had already arrived and was only waiting for him.

Khrushchev was too experienced a politician not to understand the essence of what was happening. Moreover, Mikoyan told Nikita Sergeevich what awaited him in Moscow, almost openly.

However, Khrushchev never took any measures - with a minimum number of guards, he flew to Moscow.

The reasons for Khrushchev's passivity are still being debated. Some believe that he hoped, as in 1957, to tip the scales in his favor at the last moment, having achieved a majority not at the Presidium, but at the plenum of the CPSU Central Committee. Others believe that the 70-year-old Khrushchev, entangled in his own political mistakes, saw his removal as the best way out of the situation, relieving him of any responsibility.

On October 13 at 15:30 a new meeting of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee began in the Kremlin. Arriving in Moscow, Khrushchev took the chairman's seat for the last time in his career. Brezhnev was the first to take the floor, explaining to Khrushchev what kind of questions arose in the Presidium of the Central Committee. To make Khrushchev understand that he was isolated, Brezhnev emphasized that the questions were raised by the secretaries of the regional committees.

Khrushchev did not give up without a fight. While admitting mistakes, he nevertheless expressed his willingness to correct them by continuing his work.

However, after the speech of the First Secretary, numerous speeches by critics began, lasting until the evening and continuing on the morning of October 14. The further the “enumeration of sins” went, the more obvious it became that there could be only one “sentence” - resignation. Only Mikoyan was ready to “give another chance” to Khrushchev, but his position did not find support.

When everything became obvious to everyone, Khrushchev was once again given the floor, this time truly the last. “I’m not asking for mercy - the issue is resolved. “I told Mikoyan: I won’t fight...” said Khrushchev. “I’m glad: finally the party has grown and can control any person.” You get together and say hello, but I can’t object.”

Two lines in the newspaper

It remained to decide who would become the successor. Brezhnev proposed nominating Nikolai Podgorny for the post of First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, but he refused in favor of Leonid Ilyich himself, as, in fact, was planned in advance.

The decision made by a narrow circle of leaders was to be approved by an extraordinary plenum of the CPSU Central Committee, which began on the same day, at six in the evening, in the Catherine Hall of the Kremlin.

On behalf of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee, Mikhail Suslov spoke with an ideological justification for Khrushchev’s resignation. Having announced accusations of violating the norms of the party leadership, gross political and economic mistakes, Suslov proposed a decision to remove Khrushchev from office.The Plenum of the CPSU Central Committee unanimously adopted the resolution “On Comrade Khrushchev,” according to which he was relieved of his posts “due to his advanced age and deteriorating health.”

Khrushchev combined the positions of First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR. The combination of these posts was recognized as inappropriate, and they approved Leonid Brezhnev as the party successor, and Alexei Kosygin as the “state” successor.

There was no defeat of Khrushchev in the press. Two days later, a brief report was published in the newspapers about the extraordinary plenum of the CPSU Central Committee, where it was decided to replace Khrushchev with Brezhnev. Instead of anathema, oblivion was prepared for Nikita Sergeevich - in the next 20 years, the official USSR media wrote almost nothing about the former leader of the Soviet Union.

"Voskhod" flies to another era

The “palace coup” of 1964 became the most bloodless in the history of the Fatherland. The 18-year era of Leonid Brezhnev's rule began, which would later be called the best period in the country's history in the 20th century.

The reign of Nikita Khrushchev was marked by high-profile space victories. His resignation also turned out to be indirectly connected with space. On October 12, 1964, the manned spacecraft Voskhod-1 launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome with the first crew of three in history - Vladimir Komarov, Konstantina Feoktistova And Boris Egorov. The cosmonauts flew away under Nikita Khrushchev, and reported on the successful completion of the flight program to Leonid Brezhnev...

How to find out the schedule of the exam, oge and gve

How to find out the schedule of the exam, oge and gve Criteria for evaluating the entire OGE

Criteria for evaluating the entire OGE Option Kim Unified State Exam Russian language

Option Kim Unified State Exam Russian language Formation of the correct sound pronunciation of hissing sounds in preschoolers at home Setting the sound u lesson notes

Formation of the correct sound pronunciation of hissing sounds in preschoolers at home Setting the sound u lesson notes Staging the sound sch, articulation of the sound sch Lesson on setting the sound sch

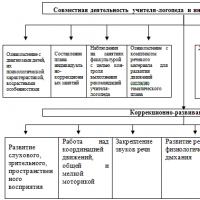

Staging the sound sch, articulation of the sound sch Lesson on setting the sound sch Interaction between a speech therapist and a teacher

Interaction between a speech therapist and a teacher A child confuses paired consonants in writing

A child confuses paired consonants in writing