Love dreams. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, alive and dead Before the evening drive, another meeting took place

It was a sunny morning. One hundred and fifty people remaining from the Serpilinsky regiment walked through the dense forests of the Dnieper left bank, hurrying to quickly move away from the crossing point. Among these one hundred and fifty people, every third was slightly wounded. The five seriously wounded, who miraculously managed to be dragged to the left bank, were replaced on stretchers by twenty of the healthiest fighters allocated for this by Serpilin.

They also carried the dying Zaichikov. He alternately lost consciousness, and then, waking up, looked at the blue sky, at the tops of pine and birch trees swaying above his head. His thoughts were confused, and it seemed to him that everything was shaking: the backs of the fighters carrying him, the trees, the sky. He listened with effort to the silence; He either imagined the sounds of battle in it, then suddenly, having come to his senses, he heard nothing, and then it seemed to him that he had gone deaf - in fact, it was just real silence.

It was quiet in the forest, only the trees creaked from the wind, the steps of tired people were heard, and sometimes the clinking of pots. The silence seemed strange not only to the dying Zaychikov, but also to everyone else. They were so unaccustomed to it that it seemed dangerous to them. Reminiscent of the utter hell of the crossing, steam from the uniforms drying out as they moved was still smoking over the column.

Having sent patrols forward and to the sides and leaving Shmakov to move with the rear guard, Serpilin himself walked at the head of the column. He moved his legs with difficulty, but to those walking behind him it seemed that he was walking easily and quickly, with the confident gait of a man who knows where he is going and is ready to walk like this for many days in a row. This gait was not easy for Serpilin: he was middle-aged, battered by life and very tired from the last days of fighting, but he knew that from now on, in the environment, there was nothing unimportant and invisible. Everything is important and noticeable, and this gait with which he walks at the head of the column is also important and noticeable.

Amazed at how easily and quickly the brigade commander walked, Sintsov followed him, shifting the machine gun from his left shoulder to his right and back: his back, neck, shoulders ached from fatigue, everything that could hurt ached.

The sunny July forest was wonderfully good! It smelled of resin and warmed moss. The sun, breaking through the swaying branches of the trees, moved on the ground with warm yellow spots. Among last year's pine needles there were green strawberry bushes with cheerful red drops of berries. The fighters kept bending down after them as they walked. For all his fatigue, Sintsov walked and never tired of noticing the beauty of the forest.

“Alive,” he thought, “still alive!” Three hours ago, Serpilin ordered him to compile a name list of everyone who crossed. He made a list and knew that there were one hundred and forty-eight people left alive. Of every four who went on a breakthrough at night, three died in battle or drowned, and only one survived - the fourth, and he himself was also like that - the fourth.

To walk and walk like this through this forest and by evening, no longer meeting the Germans, go straight to your own people - that would be happiness! And why not? The Germans were not everywhere, after all, and ours may not have retreated that far!

- Comrade brigade commander, do you think maybe we’ll reach ours today?

“I don’t know when we’ll get there,” Serpilin half-turned as he walked, “I know that we’ll get there someday.” Thanks for that for now!

He began seriously and ended with gloomy irony. His thoughts were directly opposite to Sintsov's thoughts. Judging by the map, it was possible to walk at most another twenty kilometers through continuous forest, avoiding roads, and he expected to cover them before evening. Moving further east, it was necessary not to cross the highway there, but to cross the highway here, which means meeting the Germans. To go deeper again without meeting them into the forests that were green on the map on the other side of the highway would be too amazing a success. Serpilin did not believe in it, and this meant that at night when entering the highway he would have to fight again. And he walked and thought about this future battle among the silence and greenery of the forest, which brought Sintsov into such a blissful and trusting state.

-Where is the brigade commander? Comrade brigade commander! - Seeing Serpilin, a Red Army soldier from the head patrol who ran up to him cheerfully shouted. - Lieutenant Khoryshev sent me! They met our people from 527!

- Check this out! – Serpilin responded joyfully. -Where are they?

- Out, out! – the Red Army soldier pointed his finger forward, to where the figures of military men walking towards him appeared in the thicket.

Forgetting about fatigue, Serpilin quickened his pace.

People from the 527th regiment were led by two commanders - a captain and a junior lieutenant. All of them were in uniform and with weapons. Two even carried light machine guns.

- Hello, comrade brigade commander! – stopping, the curly-haired captain in his cap pulled to one side said bravely.

Serpilin remembered that he had seen him once at the division headquarters - if memory served correctly, he was the commissioner of the Special Department.

- Hello dear! - said Serpilin. - Welcome to the division, thank you for everyone! - And he hugged him and kissed him deeply.

“Here they are, comrade brigade commander,” said the captain, touched by this kindness that was not required by the regulations. “They say the division commander is here with you.”

“Here,” said Serpilin, “they carried out the division commander, only...” Without finishing, he interrupted himself: “Now let’s go to him.”

The column stopped, everyone looked joyfully at the new arrivals. There were not many of them, but it seemed to everyone that this was just the beginning.

“Keep moving,” Serpilin said to Sintsov. “There are still twenty minutes until the required stop,” he looked at his large wrist watch.

“Lower it,” Serpilin quietly said to the soldiers carrying Zaychikov.

The soldiers lowered the stretcher to the ground. Zaichikov lay motionless, eyes closed. The joyful expression disappeared from the captain's face. Khoryshev immediately upon meeting him told him that the division commander was wounded, but the sight of Zaychikov struck him. The division commander's face, which he remembered as fat and tanned, was now thin and deathly pale. The nose was pointed, like a dead man's, and black teeth marks were visible on the bloodless lower lip. On top of the overcoat lay a white, weak, lifeless hand. The division commander was dying, and the captain knew it as soon as he saw him.

“Nikolai Petrovich, Nikolai Petrovich,” Serpilin called quietly, bending his legs aching from fatigue and kneeling on one knee next to the stretcher.

Zaichikov first rummaged through his overcoat with his hand, then bit his lip, and only then opened his eyes.

“They met our people from 527!”

- Comrade division commander, representative of the Special Department Sytin has come to your disposal! He brought with him a unit of nineteen people.

Zaichikov silently looked up and made a short, weak movement with his white fingers lying on his overcoat.

“Go lower,” Serpilin told the captain. - Calling.

Then the commissioner, like Serpilin, got down on one knee, and Zaichikov, lowering his bitten lip, whispered something to him that he did not immediately hear. Realizing from his eyes that he had not heard, Zaichikov repeated with effort what he had said.

“Brigade commander Serpilin has received the division,” he whispered, “report to him.”

“Allow me to report,” said the commissioner, without getting up from his knee, but now addressing both Zaichikov and Serpilin simultaneously, “they took out the division’s banner with them.”

One of Zaychikov’s cheeks trembled weakly. He wanted to smile, but he couldn't.

- Where is it? – he moved his lips. No whisper was heard, but the eyes asked: “Show me!” – and everyone understood it.

“Sergeant Major Kovalchuk suffered it himself,” said the commissioner. - Kovalchuk, take out the banner.

But Kovalchuk, without even waiting, unfastened his belt and, dropping it to the ground and lifting up his tunic, unwound the banner wrapped around his body. Having unwound it, he grabbed it by the edges and stretched it so that the division commander could see the entire banner - crumpled, soaked in soldier sweat, but saved, with the well-known words embroidered in gold on red silk: “176th Red Banner Rifle Division of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army "

Looking at the banner, Zaichikov began to cry. He cried as an exhausted and dying person can cry - quietly, without moving a single muscle of his face; tear after tear slowly rolled from both his eyes, and the tall Kovalchuk, holding the banner in his huge, strong hands and looking over this banner into the face of the division commander lying on the ground and crying, also began to cry, as a healthy, powerful man, shocked by what had happened, could cry, – his throat convulsively constricted from the rising tears, and his shoulders and large hands, holding the banner, shook from sobs. Zaichikov closed his eyes, his body trembled, and Serpilin frightenedly grabbed his hand. No, he didn’t die, a weak pulse continued to beat in his wrist - he just lost consciousness for the umpteenth time that morning.

“Raise the stretcher and go,” Serpilin quietly said to the soldiers, who, turning to Zaychikov, silently looked at him.

The soldiers grabbed the handles of the stretcher and, smoothly lifting them, carried them.

“Take the banner back to yourself,” Serpilin turned to Kovalchuk, who continued to stand with the banner in his hands, “once you took it out, carry it further.”

Kovalchuk carefully folded the banner, wrapped it around his body, lowered his tunic, picked up the belt from the ground and girded himself.

“Comrade junior lieutenant, line up with the soldiers at the back of the column,” Serpilin said to the lieutenant, who had also been crying a minute before, but was now standing nearby in embarrassment.

When the tail of the column passed by, Serpilin held the commissioner’s hand and, leaving an interval of ten steps between himself and the last soldiers walking in the column, walked next to the commissioner.

– Now report what you know and what you saw.

The commissioner began to talk about the last night battle. When the chief of staff of the division, Yushkevich, and the commander of the 527th regiment, Ershov, decided to break through to the east at night, the battle was difficult; They broke through in two groups with the intention of uniting later, but they did not unite. Yushkevich died in front of the commissioner, having run into German machine gunners, but the commissioner did not know whether Ershov, who commanded another group, was alive, and where he went out, if alive. By morning, he himself made his way and went out into the forest with twelve people, then met six more, led by a junior lieutenant. That was all he knew.

“Well done, commissioner,” said Serpilin. - The division banner was taken out. Who cared, you?

“Well done,” repeated Serpilin. – I made the division commander happy before his death!

- Will he die? – asked the commissioner.

- Don’t you see? – Serpilin asked, in turn. “That’s why I took the command from him.” Increase your pace, let's go catch up with the head of the column. Can you increase your step or lack strength?

“I can,” the commissioner smiled. - I am young.

- What year?

- Since the sixteenth.

“Twenty-five years,” Serpilin whistled. – Your brother’s titles will be taken away quickly!

At noon, as soon as the column had time to settle down for the first big halt, another meeting took place that pleased Serpilin. The same big-eyed Khoryshev, walking in the lead patrol, noticed a group of people located in the dense bushes. Six were sleeping side by side, and two - a fighter with a German machine gun and a female military doctor sitting in the bushes with a revolver on her knees - were guarding the sleeping people, but they were guarding poorly. Khoryshev got into trouble - he crawled out of the bushes right in front of them and shouted: “Hands up!” – and almost received a burst from a machine gun for this. It turned out that these people were also from their division, from the rear units. One of those sleeping was a technical quartermaster, the head of a food warehouse, he brought out the entire group, consisting of him, six storekeepers and sled drivers, and a female doctor who happened to spend the night in a neighboring hut.

When they were all brought to Serpilin, the quartermaster technician, a middle-aged, bald man who had already been mobilized during the war, told how three nights ago German tanks with troops on their armor burst into the village where they were standing. He and his people got out with their backs into the vegetable gardens; Not everyone had rifles, but the Germans did not want to surrender. He, a Siberian himself, a former Red partisan, undertook to lead people through the forests to his own.

“So I brought them out,” he said, “though not all of them - I lost eleven people: they ran into a German patrol.” However, four Germans were killed and their weapons were taken. “She shot one German with a revolver,” the quartermaster technician nodded at the doctor.

The doctor was young and so tiny that she seemed like just a girl. Serpilin and Sintsov, who stood next to him, and everyone around, looked at her with surprise and tenderness. Their surprise and tenderness increased even more when she, chewing a crust of bread, began to talk about herself in response to questions.

She spoke about everything that happened to her as a chain of things, each of which she absolutely needed to do. She told how she graduated from the dental institute, and then they began to take Komsomol members into the army, and she, of course, went; and then it turned out that during the war no one treated her teeth, and then she became a nurse from a dentist, because it was impossible not to do anything! When a doctor was killed in a bombing, she became a doctor because it was necessary to replace him; and she herself went to the rear for medicines, because it was necessary to get them for the regiment. When the Germans burst into the village where she spent the night, she, of course, left there along with everyone else, because she couldn’t stay with the Germans. And then, when they met a German patrol and a firefight began, one soldier in front was wounded, he was groaning heavily, and she crawled to bandage him, and suddenly a big German jumped out right in front of her, and she pulled out a revolver and killed him. The revolver was so heavy that she had to shoot while holding it with both hands.

She told all this quickly, in a childish patter, then, having finished the hump, sat down on a tree stump and began rummaging through the sanitary bag. First she pulled out several individual bags, and then a small black patent leather handbag. From his height, Sintsov saw that in her handbag were a powder compact and lipstick black with dust. Stuffing her powder compact and lipstick deeper so that no one would see them, she pulled out a mirror and, taking off her cap, began combing her baby hair, soft as fluff.

- This is a woman! - said Serpilin, when the little doctor, combing her hair and looking at the men surrounding her, somehow walked away imperceptibly and disappeared into the forest. - This is a woman! - he repeated, clapping Shmakov on the shoulder, who had caught up with the column and sat down next to him at the rest stop. - I understand it! With such a thing, it’s shameful to be a coward! “He smiled widely, flashing his steel teeth, leaned back, closed his eyes and fell asleep at that very second.

Sintsov, driving with his back along the trunk of a pine tree, squatted down, looked at Serpilin and yawned sweetly.

-Are you married? – Shmakov asked him.

Sintsov nodded and, driving away the sleep, tried to imagine how everything would have turned out if Masha then, in Moscow, had insisted on her desire to go to war with him and they had succeeded... So they would have gotten out with her from the train in Borisov... And what next? Yes, it was hard to imagine... And yet, deep down in his soul, he knew that on that bitter day of their farewell, she was right, not he.

The power of anger that he felt towards the Germans after everything he had experienced erased many of the boundaries that had previously existed in his mind; for him there were no longer any thoughts about the future without the thought that the fascists must be destroyed. And why, in fact, couldn’t Masha feel the same as him? Why did he want to take away from her that right that he won’t let anyone take away from himself, that right that you try to take away from this little doctor!

– Do you have children or not? - Shmakov interrupted his thoughts.

Sintsov, all the time, all this month, persistently convincing himself with every memory that everything was in order, that his daughter had been in Moscow for a long time, briefly explained what had happened to his family. In fact, the more forcefully he convinced himself that everything was fine, the weaker he believed in it.

Shmakov looked at his face and realized that it was better not to ask this question.

- Okay, go to sleep, the rest is short, and you won’t have time to catch your first sleep!

“What a dream now!” - Sintsov thought angrily, but after sitting for a minute with his eyes open, he pecked his nose in his knees, shuddered, opened his eyes again, wanted to say something to Shmakov, and instead, dropping his head on his chest, fell into a dead sleep.

Shmakov looked at him with envy and, taking off his glasses, began to rub his eyes with his thumb and forefinger: his eyes hurt from insomnia, it seemed that daylight was pricking them even through his closed eyelids, and sleep did not come and did not come.

Over the past three days, Shmakov saw so many dead peers of his murdered son that his father’s grief, driven by force of will into the very depths of his soul, came out of these depths and grew into a feeling that no longer applied only to his son, but also to those others who died before his eyes, and even to those whose death he did not see, but only knew about it. This feeling grew and grew and finally became so great that it turned from grief to anger. And this anger was now strangling Shmakov. He sat and thought about the fascists, who everywhere, on all the roads of war, were now trampling to death thousands and thousands of the same age of October as his son - one after another, life after life. Now he hated these Germans as much as he had once hated the whites. He did not know a greater measure of hatred, and, probably, it did not exist in nature.

Just yesterday he needed an effort above himself to give the order to shoot the German pilot. But today, after the heartbreaking scenes of the crossing, when the fascists, like butchers, used machine guns to chop the water around the heads of drowning, wounded, but still not finished people, something turned over in his soul, which until this last minute still did not want to completely turn over, and he made a rash vow to himself not to spare these murderers anywhere, under any circumstances, neither in the war, nor after the war - never!

Probably, now, when he was thinking about this, an expression so unusual appeared on his usually calm face of a naturally kind, middle-aged, intelligent man that he suddenly heard Serpilin’s voice:

- Sergey Nikolaevich! What happened to you? What happened?

Serpilin lay on the grass and, with his eyes wide open, looked at him.

- Absolutely nothing. – Shmakov put on his glasses, and his face took on its usual expression.

- And if nothing, then tell me what time it is: isn’t it time? “I’m too lazy to move my limbs in vain,” Serpilin chuckled.

Shmakov looked at his watch and said that there were seven minutes left until the end of the halt.

“Then I’m still sleeping.” – Serpilin closed his eyes.

After an hour's rest, which Serpilin, despite the fatigue of the people, did not allow to drag on for a minute, we moved on, gradually turning to the southeast.

Before the evening halt, the detachment was joined by another three dozen people wandering through the forest. No one else from their division was caught. All thirty people met after the first halt were from the neighboring division, stationed to the south along the left bank of the Dnieper. All these were people from different regiments, battalions and rear units, and although among them there were three lieutenants and one senior political instructor, no one had any idea where the division headquarters was, or even in what direction it was departing. However, based on fragmentary and often contradictory stories, it was still possible to imagine the overall picture of the disaster.

Judging by the names of the places from which the encirclement came, by the time of the German breakthrough the division was stretched out in a chain for almost thirty kilometers along the front. In addition, she did not have time or was unable to strengthen herself properly. The Germans bombed it for twenty hours straight, and then, having dropped several landing forces into the rear of the division and disrupted control and communications, at the same time, under the cover of aviation, they began crossing the Dnieper in three places at once. Parts of the division were crushed, in some places they fled, in others they fought fiercely, but this could no longer change the general course of things.

People from this division walked in small groups, twos and threes. Some were with weapons, others without weapons. Serpilin, after talking with them, put them all in line, mixing them with his own fighters. He put the unarmed in formation without weapons, saying that they would have to get it themselves in battle, it was not stored for them.

Serpilin talked to people coolly, but not offensively. Only to the senior political instructor, who justified himself by the fact that although he was walking without a weapon, but in full uniform and with a party card in his pocket, Serpilin bitterly objected that a communist at the front should keep weapons along with his party card.

“We are not going to Golgotha, dear comrade,” said Serpilin, “but we are fighting.” If it’s easier for you to be put up against the wall by the fascists than to tear down the commissar’s stars with your own hands, that means you have a conscience. But this alone is not enough for us. We don’t want to stand up to the wall, but to put the fascists against the wall. But you can’t do this without a weapon. That's it! Go into the ranks, and I expect that you will be the first to acquire weapons in battle.

When the embarrassed senior political instructor walked away a few steps, Serpilin called out to him and, unhooking one of the two lemon grenades hanging from his belt, held it out in his palm.

- First, take it!

Sintsov, who, as an adjutant, wrote down names, ranks and unit numbers in a notebook, silently rejoiced at the reserve of patience and calm with which Serpilin spoke with people.

It is impossible to penetrate into the soul of a person, but during these days Sintsov more than once thought that Serpilin himself did not experience the fear of death. It probably wasn't like that, but it looked like it.

At the same time, Serpilin did not pretend that he did not understand how people were afraid, how they could run, get confused, and throw down their weapons. On the contrary, he made them feel that he understood this, but at the same time persistently instilled in them the idea that the fear they experienced and the defeat they experienced were all in the past. That it was like that, but it won’t be like that anymore, that they lost their weapons, but can acquire them again. This is probably why people did not leave Serpilin depressed, even when he spoke coolly to them. He rightly did not absolve them of blame, but he did not place all the blame solely on their shoulders. People felt it and wanted to prove that he was right.

Before the evening halt, another meeting took place, unlike all the others. A sergeant came from a side patrol moving through the thicket of the forest, bringing with him two armed men. One of them was a short Red Army soldier, wearing a shabby leather jacket over a tunic and with a rifle on his shoulder. The other is a tall, handsome man of about forty, with an aquiline nose and noble gray hair visible from under his cap, giving significance to his youthful, clean, wrinkle-free face; he was wearing good riding breeches and chrome boots, a brand new PPSh with a round disk was hanging on his shoulder, but the cap on his head was dirty and greasy, and just as dirty and greasy was the Red Army tunic that sat awkwardly on him, which did not meet at the neck and was short in the sleeves .

“Comrade brigade commander,” the sergeant said, approaching Serpilin along with these two people, looking sideways at them and holding his rifle at the ready, “permit me to report?” He brought the detainees. He detained them and brought them under escort because they did not explain themselves, and also because of their appearance. They didn’t disarm because they refused, and we didn’t want to open fire in the forest unnecessarily.

“Deputy Chief of the Operations Department of the Army Headquarters, Colonel Baranov,” the man with the machine gun said abruptly, throwing his hand to his cap and stretching out in front of Serpilin and Shmakov, who was standing next to him.

“We apologize,” the sergeant who brought the detainees said, having heard this and, in turn, putting his hand to his cap.

- Why are you apologizing? – Serpilin turned to him. “They did the right thing in detaining me, and they did the right thing in bringing me to me.” Continue to do so in the future. You can go. “I’ll ask for your documents,” releasing the sergeant, he turned to the detainee, without calling him by rank.

His lips trembled and he smiled in confusion. It seemed to Sintsov that this man probably knew Serpilin, but only now recognized him and was amazed by the meeting.

And so it was. The man who called himself Colonel Baranov and actually bore this name and rank and held the position that he named when he was brought to Serpilin was so far from the idea that in front of him here, in the forest, in military uniform, surrounded by other commanders , it may turn out to be Serpilin, who in the first minute only noted to himself that the tall brigade commander with a German machine gun on his shoulder reminded him very much of someone.

- Serpilin! - he exclaimed, spreading his arms, and it was difficult to understand whether this was a gesture of extreme amazement, or whether he wanted to hug Serpilin.

“Yes, I am brigade commander Serpilin,” Serpilin said in an unexpectedly dry, tinny voice, “the commander of the division entrusted to me, but I don’t see who you are yet.” Your documents!

- Serpilin, I’m Baranov, are you crazy?

“For the third time I ask you to present your documents,” Serpilin said in the same tinny voice.

“I don’t have documents,” Baranov said after a long pause.

- How come there are no documents?

- It happened that I accidentally lost... I left it in that tunic when I exchanged it for this... Red Army one. – Baranov moved his fingers along his greasy, too-tight tunic.

– Did you leave the documents in that tunic? Do you also have the colonel’s insignia on that tunic?

“Yes,” Baranov sighed.

– Why should I believe you that you are the deputy chief of the army’s operational department, Colonel Baranov?

- But you know me, we served together at the academy! – Baranov muttered completely lost.

“Let’s assume that this is so,” Serpilin said without softening at all, with the same tinny harshness unusual for Sintsov, “but if you had not met me, who could confirm your identity, rank and position?”

“Here he is,” Baranov pointed to the Red Army soldier in a leather jacket standing next to him. - This is my driver.

– Do you have documents, comrade soldier? – Without looking at Baranov, Serpilin turned to the Red Army soldier.

“Yes...” the Red Army soldier paused for a second, not immediately deciding how to address Serpilin, “yes, comrade general!” “He opened his leather jacket, took out a Red Army book wrapped in a rag from the pocket of his tunic and handed it to him.

“Yes,” Serpilin read aloud. - “Red Army soldier Petr Ilyich Zolotarev, military unit 2214.” Clear. - And he gave the Red Army soldier the book. – Tell me, Comrade Zolotarev, can you confirm the identity, rank and position of this man with whom you were detained? - And he, still not turning to Baranov, pointed his finger at him.

– That’s right, Comrade General, this is really Colonel Baranov, I’m his driver.

- So you certify that this is your commander?

- That's right, Comrade General.

- Stop mocking, Serpilin! – Baranov shouted nervously.

But Serpilin didn’t even bat an eyelid in his direction.

“It’s good that at least you can verify the identity of your commander, otherwise, at any moment, you could shoot him.” There are no documents, no insignia, a tunic from someone else’s shoulder, boots and breeches from command staff... - Serpilin’s voice became harsher and harsher with each phrase. – Under what circumstances did you end up here? – he asked after a pause.

“Now I’ll tell you everything...” Baranov began.

But Serpilin, this time half turning around, interrupted him:

- I'm not asking you yet. Speak... - he turned to the Red Army soldier again.

The Red Army soldier, at first hesitating, and then more and more confidently, trying not to forget anything, began to tell how three days ago, having arrived from the army, they spent the night at the division headquarters, how in the morning the colonel went to headquarters, and bombing immediately began all around, how soon one arrived From the rear, the driver said that German troops had landed there, and when he heard this, he took the car out just in case. And an hour later the colonel came running, praised him that the car was already ready, jumped into it and ordered him to quickly drive back to Chausy. When they got onto the highway, there was already heavy shooting and smoke ahead, they turned onto a dirt road, drove along it, but again heard shooting and saw German tanks at the intersection. Then they turned onto a remote forest road, drove straight off it into the forest, and the colonel ordered the car to stop.

While telling all this, the Red Army soldier sometimes glanced sideways at his colonel, as if seeking confirmation from him, and he stood silently, with his head bowed low. The hardest part was beginning for him, and he understood it.

“I ordered to stop the car,” Serpilin repeated the last words of the Red Army soldier, “and what next?”

“Then Comrade Colonel ordered me to take out my old tunic and cap from under the seat, I had just recently received new uniforms, and left the old tunic and cap with me - just in case they were lying under the car. Comrade Colonel took off his tunic and cap and put on my cap and tunic, said that now I would have to leave the encirclement on foot, and ordered me to pour gasoline on the car and set it on fire. But only I,” the driver hesitated, “but only I, Comrade General, did not know that Comrade Colonel forgot his documents there, in his tunic, I would, of course, remind you if I knew, otherwise I set everything on fire along with the car.” .

He felt guilty.

- You hear? – Serpilin turned to Baranov. – Your fighter regrets that he did not remind you about your documents. – There was mockery in his voice. – I wonder what would happen if he reminded you of them? - He turned to the driver again: - What happened next?

“Thank you, Comrade Zolotarev,” said Serpilin. – Put him on the list, Sintsov. Catch up with the column and get into formation. You will receive satisfaction at the rest stop.

The driver started to move, then stopped and looked questioningly at his colonel, but he still stood with his eyes lowered to the ground.

- Go! - Serpilin said commandingly. - You are free.

The driver left. There was a heavy silence.

“Why did you need to ask him in front of me?” They could have asked me without compromising myself in front of the Red Army soldier.

“And I asked him because I trust the story of a soldier with a Red Army book more than the story of a disguised colonel without insignia and documents,” said Serpilin. – Now, at least, the picture is clear to me. We came to the division to monitor the implementation of the orders of the army commander. So or not?

“Yes,” Baranov said, looking stubbornly at the ground.

- But instead they ran away at the first danger! They abandoned everything and ran away. So or not?

- Not really.

- Not really? But as?

But Baranov was silent. No matter how much he felt insulted, there was nothing to object to.

“I compromised him in front of the Red Army soldier!” Do you hear, Shmakov? – Serpilin turned to Shmakov. - Like laughter! He chickened out, took off his command tunic in front of the Red Army soldier, threw away his documents, and it turns out I compromised him. It was not I who compromised you in front of the Red Army soldier, but you, with your shameful behavior, compromised the command staff of the army in front of the Red Army soldier. If my memory serves me correctly, you were a party member. Did they burn the party card too?

“Everything burned,” Baranov threw up his hands.

– Are you saying that you accidentally forgot all the documents in your tunic? – Shmakov, who entered this conversation for the first time, quietly asked.

- Accidentally.

- But in my opinion, you are lying. In my opinion, if your driver reminded you of them, you would still get rid of them at the first opportunity.

- For what? – asked Baranov.

- You know better than that.

“But I came with a weapon.”

– If you burned the documents when there was no real danger, then you would have thrown your weapons in front of the first German.

“He kept the weapon for himself because he was afraid of wolves in the forest,” said Serpilin.

“I left my weapons against the Germans, against the Germans!” – Baranov shouted nervously.

“I don’t believe it,” said Serpilin. “You, the staff commander, had an entire division at your disposal, so you ran away from it!” How can you fight the Germans alone?

- Fyodor Fedorovich, why talk for a long time? “I’m not a boy, I understand everything,” Baranov suddenly said quietly.

But it was precisely this sudden humility, as if a person who had just considered it necessary to justify himself with all his might suddenly decided that it would be more useful for him to speak differently, caused a sharp surge of distrust in Serpilin.

- What do you understand?

- My guilt. I'll wash it away with blood. Give me a company, finally, a platoon, after all, I wasn’t going to the Germans, but to my own people, can you believe it?

“I don’t know,” said Serpilin. - In my opinion, you didn’t go to anyone. We just walked depending on the circumstances, how it turned out...

“I curse the hour when I burned the documents...” Baranov began again, but Serpilin interrupted him:

– I believe that you regret it now. You regret that you were in a hurry, because you ended up with your own people, but if it had turned out differently, I don’t know, you would have regretted it. “How, commissar,” he turned to Shmakov, “shall we give this former colonel a company to command?”

“No,” said Shmakov.

- I think so too. After everything that happened, I would sooner trust your driver to command you than you to command him! - said Serpilin and for the first time, half a tone softer than anything said before, he addressed Baranov: “Go and get into formation with this brand new machine gun of yours and try, as you say, to wash away your guilt with the blood of... the Germans,” he added after a pause. - And yours will need it too. By the authority given to me and the commissar here, you have been demoted to the rank and file until we come out to our own people. And there you will explain your actions, and we will explain our arbitrariness.

- All? Don't you have anything else to tell me? – Baranov asked, looking up at Serpilin with angry eyes.

Something trembled in Serpilin’s face at these words; he even closed his eyes for a second to hide their expression.

“Be grateful that you weren’t shot for cowardice,” Shmakov snapped instead of Serpilin.

“Sintsov,” said Serpilin, opening his eyes, “put fighter Baranov’s units on the lists.” Go with him,” he nodded towards Baranov, “to Lieutenant Khoryshev and tell him that the fighter Baranov is at his disposal.

“Your power, Fedor Fedorovich, I will do everything, but don’t expect me to forget this for you.”

Serpilin put his hands behind his back, cracked his wrists and said nothing.

“Come with me,” Sintsov said to Baranov, and they began to catch up with the column that had gone ahead.

Shmakov looked intently at Serpilin. Himself agitated by what had happened, he felt that Serpilin was even more shocked. Apparently, the brigade commander was very upset by the shameful behavior of his old colleague, of whom, probably, he had previously had a completely different, high opinion.

- Fedor Fedorovich!

- What? - Serpilin responded as if half asleep, even shuddering: he was lost in his thoughts and forgot that Shmakov was walking next to him, shoulder to shoulder.

- Why are you upset? How long did you serve together? Did you know him well?

Serpilin looked at Shmakov with an absent-minded gaze and answered with an evasiveness unlike himself that surprised the commissar:

– But you never know who knew who! Let's pick up the pace before we stop!

Shmakov, who did not like to intrude, fell silent, and they both, quickening their pace, walked side by side until the halt, without saying a word, each busy with their own thoughts.

Shmakov didn’t guess right. Although Baranov actually served with Serpilin at the academy, Serpilin not only did not have a high opinion of him, but, on the contrary, had the worst opinion. He considered Baranov to be a not incapable careerist, who was not interested in the benefit of the army, but only in his own career advancement. Teaching at the academy, Baranov was ready to support one doctrine today and another tomorrow, to call white black and black white. Cleverly applying himself to what he thought might be liked “at the top,” he did not disdain to support even direct misconceptions based on ignorance of facts that he himself knew perfectly well.

His specialty was reports and messages about the armies of supposed opponents; looking for real and imaginary weaknesses, he obsequiously kept silent about all the strong and dangerous sides of the future enemy. Serpilin, despite all the complexity of conversations on such topics at that time, scolded Baranov twice for this in private, and the third time publicly.

He later had to remember this under completely unexpected circumstances; and only God knows how hard it was for him now, during his conversation with Baranov, not to express everything that suddenly stirred in his soul.

He didn’t know whether he was right or wrong in thinking about Baranov what he thought about him, but he knew for sure that now was not the time or place for memories, good or bad - it doesn’t matter!

The most difficult moment in their conversation was the moment when Baranov suddenly looked questioningly and angrily into his eyes. But, it seems, he withstood this look, and Baranov left reassured, at least judging by his farewell insolent phrase.

Well, so be it! He, Serpilin, does not want and cannot have any personal accounts with the fighter Baranov, who is under his command. If he fights bravely, Serpilin will thank him in front of the line; if he honestly lays down his head, Serpilin will report this; if he becomes cowardly and runs away, Serpilin will order to shoot him, just as he would order to shoot anyone else. Everything is correct. But how hard it is on my soul!

We made a halt near human habitation, which was found in the forest for the first time that day. On the edge of the wasteland plowed for a vegetable garden stood an old forester's hut. There was also a well nearby, which brought joy to the people exhausted by the heat.

Sintsov, having taken Baranov to Khoryshev, went into the hut. It consisted of two rooms; the door to the second was closed; From there a long, aching female cry could be heard. The first room was papered over the logs with old newspapers. In the right corner hung a shrine with poor, without vestments, icons. On a wide bench next to two commanders who entered the hut before Sintsov, a stern eighty-year-old man, dressed in everything clean - a white shirt and white ports, sat motionless and silent. His whole face was carved with wrinkles, deep as cracks, and on his thin neck a pectoral cross hung on a worn copper chain.

A small, nimble woman, probably the same age as the old man in years, but who seemed much younger than him because of her quick movements, greeted Sintsov with a bow, took another cut glass from the towel-hung wall shelf and placed it in front of Sintsov on the table, where there were already two glasses. and a bucket. Before Sintsov arrived, the grandmother treated the commanders who came into the hut with milk.

Sintsov asked her if it was possible to collect something to eat for the division commander and commissar, adding that they had their own bread.

- What can I treat you with now, just milk? “The grandmother threw up her hands sadly. - Just light the stove and cook some potatoes, if you have time.

Sintsov didn’t know if there was enough time, but he asked to boil some potatoes just in case.

“There are still some old potatoes left, last year’s ones...” said the grandmother and began to bustle around by the stove.

Sintsov drank a glass of milk; he wanted to drink more, but, looking into the bucket, which had less than half left, he was embarrassed. Both commanders, who probably also wanted to drink another glass, said goodbye and left. Sintsov stayed with the grandmother and the old man. After fussing around the stove and placing a splinter under the firewood, the grandmother went into the next room and returned a minute later with matches. Both times she opened and closed the door, a loud, whining cry came out in bursts.

- What is it about you who is crying? – asked Sintsov.

- Dunka is crying, my granddaughter. Her boyfriend was killed. He is withered, they didn’t take him to the war. They drove a collective farm herd out of Nelidovo, he went with the herd, and as they crossed the highway, bombs were dropped on them and they were killed. It’s been howling for the second day,” the grandmother sighed.

She lit a torch, put a cast iron on the fire with some potatoes that had already been washed, probably for herself, then sat down next to her old man on the bench and, leaning her elbows on the table, became sad.

- We are all at war. Sons at war, grandchildren at war. Will the German come here soon, eh?

- Don't know.

“They came from Nelidov and said that the German was already in Chausy.”

- Don't know. – Sintsov really didn’t know what to answer.

“It should be soon,” said the grandmother. “They’ve been driving the herds for five days already, they wouldn’t have done it in vain.” And here we are,” she pointed to the bucket with a dry hand, “drinking the last milk.” They also gave away the cow. Let them drive, God willing, when they will drive back. A neighbor said that there are few people left in Nelidovo, everyone is leaving...

She said all this, and the old man sat and was silent; During the entire time that Sintsov was in the hut, he never said a single word. He was very old and seemed to want to die now, without waiting for the Germans to follow these people in Red Army uniforms into his hut. And such sadness overwhelmed me when I looked at him, such melancholy was heard in the aching women’s sobs behind the wall, that Sintsov could not stand it and left, saying that he would be right back.

As soon as he came down from the porch, he saw Serpilin approaching the hut.

“Comrade brigade commander...” he began.

But, ahead of him, a former little doctor ran up to Serpilin and, worried, said that Colonel Zaichikov asked him to come to him right away.

“Then I’ll come in if I have time,” Serpilin waved his hand in response to Sintsov’s request to go and rest in the hut and followed the little doctor with leaden steps.

Zaichikov was lying on a stretcher in the shade, under thick hazel bushes. He had just been given water to drink; He probably swallowed it with difficulty: his tunic collar and shoulders were wet.

– I’m here, Nikolai Petrovich. – Serpilin sat down on the ground next to Zaychikov.

Zaichikov opened his eyes so slowly, as if even this movement required incredible effort from him.

“Listen, Fedya,” he said in a whisper, addressing Serpilin in this way for the first time, “shoot me.” There is no strength to suffer, do a favor.

- If only I suffered myself, otherwise I’m burdening everyone. – Zaychikov breathed out every word with difficulty.

“I can’t,” Serpilin repeated.

“Give me the gun, I’ll shoot myself.”

Serpilin was silent.

– Are you afraid of responsibility?

“You can’t shoot yourself,” Serpilin finally gathered his courage, “you have no right.” It will have an effect on people. If you and I walked together...

He did not finish the sentence, but the dying Zaichikov not only understood, but also believed that, if they were together, Serpilin would not have denied him the right to shoot himself.

“Oh, how I suffer,” he closed his eyes, “how I suffer, Serpilin, if you only knew, I have no strength!” Put me to sleep, order the doctor to put me to sleep, I asked her - she won’t give it, she says, no. Check it out, maybe he's lying?

Now he lay motionless again, eyes closed and lips pursed. Serpilin stood up and, stepping aside, called the doctor to him.

- Hopeless? – he asked quietly.

She just clasped her little hands.

- What are you asking? Three times already I thought I was completely dying. There are only a few hours left to live, the longest.

- Do you have anything to put him to sleep? – Serpilin asked quietly but decisively.

The doctor looked at him in fear with big, childish eyes.

- This is impossible!

– I know it’s impossible, my responsibility. Yes or not?

“No,” said the doctor, and it seemed to him that she was not lying.

“I don’t have the strength to watch a person suffer.”

– Do you think I have strength? - she answered and, unexpectedly for Serpilin, began to cry, smearing tears across her face.

Serpilin turned away from her, walked up to Zaychikov and sat down next to him, peering into his face.

Before death, this face became haggard and became younger from thinness. Serpilin suddenly remembered that Zaichikov was a full six years younger than him and by the end of the Civil War he was still a young platoon commander, when he, Serpilin, was already commanding a regiment. And from this distant memory, the bitterness of the elder, in whose arms the younger one was dying, gripped the soul of one, no longer young, man over the body of another.

“Ah, Zaichikov, Zaichikov,” Serpilin thought, “there weren’t enough stars in the sky when he was on my internship, he served in different ways - both better and worse than others, then he fought in the Finnish war, probably bravely: two orders won’t give for nothing, Yes, even at Mogilev, you didn’t chicken out, didn’t get confused, commanded while you stood on your feet, and now you’re lying and dying here in the forest, and you don’t know and will never know when and where this war will end... in which you’ve been I started to take a sip of such grief...”

No, he was not in oblivion, he lay there and thought about almost the same thing that Serpilin was thinking about.

“It would be fine,” Zaichikov closed his eyes, “it would just hurt a lot.” Go, you have things to do! – he said very quietly, with force, and again bit his lip in pain...

At eight o'clock in the evening, Serpilin's detachment approached the southeastern part of the forest. Further, judging by the map, there was another two kilometers of small forest, and behind it ran a highway that could not be avoided. Beyond the road there was a village, a strip of arable land, and only then the forests began again. Before reaching the small forest, Serpilin arranged for the people to rest, in anticipation of the battle and the night march immediately following the battle. People needed to eat and sleep. Many had been dragging their feet for a long time, but they walked with all their strength, knowing that if they did not reach the highway before evening and did not cross it at night, then all their previous efforts were meaningless - they would have to wait for the next night.

Having walked around the detachment's location, checked the patrols and sent reconnaissance to the highway, Serpilin, waiting for her return, decided to rest. But he did not succeed immediately. As soon as he had chosen a place on the grass under a shady tree, Shmakov sat down next to him and, taking out his riding breeches from his pocket, thrust into his hand a withered German leaflet that had probably been lying in the forest for several days.

- Come on, be curious. The soldiers found it and brought it. They must be dropped from planes.

Serpilin rubbed his eyes, which were drooping from lack of sleep, and conscientiously read the leaflet, all of it, from beginning to end. It reported that Stalin's armies had been defeated, that six million people had been taken prisoner, that German troops had taken Smolensk and were approaching Moscow. This was followed by the conclusion: further resistance is useless, and the conclusion was followed by two promises: “to save the lives of everyone who voluntarily surrenders, including command and political personnel” and “to feed the prisoners three times a day and keep them in conditions generally accepted in the civilized world." The back of the leaflet had a sweeping diagram printed on it; Of the names of cities, only Minsk, Smolensk and Moscow were on it, but in general terms the northern arrow of the advancing German armies went far beyond Vologda, and the southern arrow ended somewhere between Penza and Tambov. The middle arrow, however, barely reached Moscow - the authors of the leaflet had not yet decided to occupy Moscow.

“Yes,” Serpilin said mockingly and, bending the leaflet in half, returned it to Shmakov. – Even you, commissar, it turns out, they promise life. How about we give up, huh?

“Even the smarter Denikinites concocted such pieces of paper. – Shmakov turned to Sintsov and asked if he had any matches left.

Sintsov pulled out matches from his pocket and wanted to burn the leaflet handed to him by Shmakov without reading, but Shmakov stopped him:

- And read it, it’s not contagious!

Sintsov read the leaflet with an insensitivity that surprised even him. He, Sintsov, the day before yesterday and yesterday, first with a rifle, and then with a German machine gun, with his own hands, killed two fascists, maybe more, but he killed two - that’s for sure; he wanted to continue killing them, and this leaflet did not apply to him...

Meanwhile, Serpilin, like a soldier, without wasting too much time, settled down to rest under his favorite tree. To Sintsov’s surprise, among the few most necessary things in Serpilin’s field bag was a four-fold rubber pad. With a funny bubble on his thin cheeks, Serpilin inflated it and placed it under his head with pleasure.

– I take it with me everywhere, a gift from my wife! - He smiled at Sintsov, who was looking at these preparations, without adding that the pillow was especially memorable for him: sent from home by his wife several years ago, it traveled with him to Kolyma and back.

Shmakov did not want to go to bed while Serpilin slept, but he persuaded him.

“Anyway, you and I won’t be able to take turns today.” You have to stay awake at night - what the hell, you'll have to fight. And no one can fight without sleep, not even commissars! At least for an hour, but please close your eyes like a chicken on the roost.

Having ordered to wake himself up as soon as intelligence returned, Serpilin blissfully stretched out on the grass. After turning a little from side to side, Shmakov also fell asleep. Sintsov, to whom Serpilin had not given any orders, had difficulty overcoming the temptation to also lie down and fall asleep. If Serpilin had directly told him that he could sleep, he would not have been able to stand it and lie down, but Serpilin said nothing, and Sintsov, fighting sleep, began pacing back and forth in the small clearing where the brigade commander and the commissar were lying under a tree.

Previously, he had only heard that people fall asleep while walking, now he experienced it himself, sometimes suddenly stopping and losing his balance.

“Comrade political instructor,” he heard Khoryshev’s quiet, familiar voice behind him.

- What's happened? - asked Sintsov, turning around and noticing with alarm the signs of deep excitement on the lieutenant’s usually calmly cheerful boyish face.

- Nothing. The weapon was found in the forest. I want to report to the brigade commander.

Khoryshev still spoke quietly, but Serpilin was probably awakened by the word “weapon.” He sat down, leaning on his hands, looked back at the sleeping Shmakov and quietly stood up, making a sign with his hand not to report loudly and not to wake up the commissar. Having straightened his tunic and beckoning Sintsov to follow him, he walked a few steps into the depths of the forest. And only then did he finally give Khoryshev the opportunity to report.

-What kind of weapon? German?

- Is our. And he has five soldiers with him.

-What about the shells?

- One shell left.

- Not rich. How far is it from here?

- Five hundred steps.

Serpilin shrugged his shoulders, shaking off the remnants of sleep, and told Khoryshev to take him to the gun.

On the way, Sintsov wanted to find out why the always calm lieutenant had such an excited face, but Serpilin walked the whole way in silence, and Sintsov was uncomfortable breaking this silence.

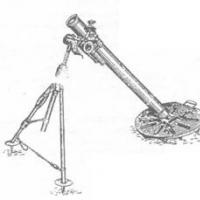

After five hundred steps, they actually saw a 45-mm anti-tank gun standing in the thick of a young spruce forest. Near the cannon, on a thick layer of red old pine needles, sat mixed Khoryshev’s fighters and the five artillerymen about whom he reported to Serpilin.

When the brigade commander appeared, everyone stood up, the artillerymen a little later than the others, but still earlier than Khoryshev had time to give the command.

- Hello, comrade artillerymen! - said Serpilin. – Who is your eldest?

A sergeant major stepped forward wearing a cap with a visor broken in half and a black artillery band. In place of one eye he had a swollen wound, and the upper eyelid of the other eye was trembling from tension. But he stood firmly on the ground, as if his feet in tattered boots were nailed to it; and he raised his hand with the torn and burnt sleeve to the broken visor, as if on a spring; and in a thick and strong voice, he reported that he, the foreman of the ninth separate anti-tank division Shestakov, was currently the senior commanding officer, having fought with the remaining material from the city of Brest.

- Where, where from? – asked Serpilin, who thought he had misheard.

“From near the city of Brest, where the full strength of the division took place in the first battle with the Nazis,” the foreman did not say, but cut off.

There was silence.

Serpilin looked at the gunners, wondering if what he had just heard could be true. And the longer he looked at them, the clearer it became to him that this incredible story was the real truth, and what the Germans wrote in their leaflets about their victory was only a plausible lie and nothing more.

Five blackened faces, touched by hunger, five pairs of tired, overworked hands, five worn out, dirty, tunics whipped by branches, five German machine guns taken in battle and a cannon, the last cannon of the division, not in the sky, but on the ground, not by miracle, but by soldiers dragged here by hand from the border, more than four hundred miles away... No, you’re lying, gentlemen, fascists, it won’t be your way!

- On yourself, or what? – Serpilin asked, swallowing the lump in his throat and nodding towards the cannon.

The foreman answered, and the rest, unable to bear it, supported him in unison, which happened in different ways: they walked on horseback, and pulled them in their hands, and again got hold of horses, and again in their hands...

– What about through water barriers, here, through the Dnieper, how? – Serpilin asked again.

- By raft, the night before last...

“But we haven’t transported a single one,” Serpilin suddenly said, but although he looked around at all his people, they felt that he was now reproaching only one person - himself.

Then he looked at the gunners again:

- They say you have shells too?

“One, the last one,” the foreman said guiltily, as if he had overlooked and failed to restore the ammunition in time.

– Where did you spend the penultimate one?

- Here, ten kilometers away. “The sergeant-major pointed his hand back to where the highway passed behind the forest. “Last night we drove out to the highway into the bushes, at direct fire, and at the convoy, into the lead car, straight into the headlights!”

- Aren’t you afraid that they’ll comb the forest?

- Tired of being afraid, Comrade Brigade Commander, let them be afraid of us!

- So you didn’t comb it?

- No. They just threw mines all around. The division commander was mortally wounded.

- And where he? – Serpilin quickly asked and, before he had time to finish, he already understood where...

To the side, where the sergeant-major directed his eyes, under a huge, old, bare pine tree, a freshly filled grave was yellowing to the very top; even the wide German cleaver used to cut the turf to line the grave, not yet removed, stuck out of the ground like an unbidden cross. There was still a rough, criss-crossed notch on the pine tree that was still oozing resin. And two more such evil notches were on the pines to the right and left of the grave, like a challenge to fate, like a silent promise to return.

Serpilin walked up to the grave and, pulling his cap off his head, looked at the ground silently for a long time, as if trying to see through it something that no one had ever been able to see - the face of a man who, with battles, brought everything from Brest to this Trans-Dnieper forest. what was left of his division: five fighters and a cannon with the last shell.

Serpilin had never seen this man, but it seemed to him that he knew well what kind of man he was. One for whom soldiers go through fire and water, one whose dead body, sacrificing life, is carried out of battle, one whose orders are carried out even after death. The kind of person you have to be to take out this gun and these people. But these people whom he brought out were worth their commander. He was like that because he walked with them...

Serpilin put on his cap and silently shook hands with each of the artillerymen. Then he pointed to the grave and asked abruptly:

- What's your last name?

- Captain Gusev.

- Don't write it down. – Serpilin saw that Sintsov took up the tablet. “And I won’t forget it until the hour of death.” But we are all mortal, write it down! And put the artillerymen on the combat list! Thank you for your service, comrades! And I think we’ll fire your last shell tonight, in battle.

Among Khoryshev’s fighters standing with the artillerymen, Serpilin had long noticed Baranov’s gray head, but only now met his gaze, eye to eye, and read in those eyes, which had not had time to hide from him, the fear of the thought of a future battle.

“Comrade brigade commander,” the small figure of the doctor’s wife appeared from behind the fighters, “the colonel is calling you!”

- Colonel? – Serpilin asked. He was now thinking about Baranov and did not immediately realize which colonel was calling him. “Yes, let’s go, let’s go,” he said, realizing that the doctor was talking about Zaichikov.

- What's happened? Why didn't they invite me? – the doctor’s wife exclaimed sadly, clenching her palms in front of her, noticing the people crowded over the fresh grave.

- It’s okay, let’s go, it was too late to call you! “Serpilin, with rude affection, put his large hand on her shoulder, almost forcibly turned her and, still holding his hand on her shoulder, walked with her.

“Without faith, without honor, without conscience,” he continued to think about Baranov, walking next to the doctor. “While the war seemed far away, I shouted that we would throw our hats, but when it came, I was the first to run.” Since he was scared, since he is scared, it means that everything is already lost, we will no longer win! No matter how it is! Besides you, there is also Captain Gusev, and his artillerymen, and we, sinners, living and dead, and this little doctor, who holds a revolver with both hands...”

Serpilin suddenly felt that his heavy hand was still lying on the doctor’s thin shoulder, and not only lying, but even leaning on this shoulder. And she walks along and doesn’t seem to notice, she even seems to have deliberately raised her shoulder. He walks and probably doesn’t suspect that there are people like Baranov in the world.

“You see, I forgot my hand on your shoulder,” he said to the doctor in a dull, gentle voice and removed his hand.

- It’s okay, you can lean on it if you’re tired. I know how strong I am.

“Yes, you are strong,” Serpilin thought to himself, “we won’t be lost with people like you, that’s true.” He wanted to say something affectionate and confident to this little woman, which would be an answer to his own thoughts about Baranov, but he couldn’t find what exactly to say to her, and they silently walked to the place where Zaichikov lay.

“Comrade Colonel, I brought you,” the doctor said quietly, being the first to kneel next to the stretcher with Zaychikov.

Serpilin also knelt down next to her, and she moved to the side so as not to interfere with him leaning closer to Zaychikov’s face.

- Is that you, Serpilin? – Zaichikov asked in an indistinct whisper.

“Listen to what I tell you,” Zaichikov said even more quietly and fell silent.

Serpilin waited a minute, two, three, but he was never destined to find out what exactly the former commander wanted to tell the new division commander.

“He died,” the doctor said barely audibly.

Serpilin slowly took off his cap, stood on his knees for a minute with his head uncovered, straightened his knees with effort, stood up and, without saying a word, walked back.

The returning scouts reported that there were German patrols on the highway and cars were moving towards Chaus.

“Well, as you can see, we’ll have to fight,” said Serpilin. – Raise and build people!

Now, having learned that his assumptions were confirmed and that it would hardly be possible to cross the highway without a fight, he finally shook off the feeling of physical fatigue that had been oppressing him since the morning. He was determined to bring all these people rising from sleep with weapons in their hands to where he had to bring them - to his own! He did not think about anything else and did not want to think, because nothing else suited him.

He did not know and could not yet know that night the full price of everything that had already been accomplished by the people of his regiment. And, like him and his subordinates, the full price of their deeds was not yet known to thousands of other people who, in thousands of other places, fought to the death with persistence unplanned by the Germans.

They did not know and could not know that the generals of the German army, still victoriously advancing on Moscow, Leningrad and Kyiv, fifteen years later would call this July of 1941 a month of disappointed expectations, successes that did not become a victory.

They could not foresee these future bitter confessions of the enemy, but almost each of them then, in July, had a hand in ensuring that all this happened exactly like that.

Serpilin stood listening to the quiet commands reaching him. The column moved discordantly in the darkness that had fallen over the forest. A flat, crimson moon rose above its jagged tops. The first day of leaving the encirclement was over...

It is difficult for victims of femininity and sexuality training to adapt to schemes that actually work in relationships with men.

Other ladies write that they have an “8 dates” rule before first sex, and that they voice this rule during the first few meetings, which guys usually accept with understanding.

Why does this work? Because the girl speaks honestly about her rules right away, and does not wag her tail. If the guy doesn't agree, he can stop courtship. But if he agrees, then he knows that if he lasts 8 dates, there is no need to take the fortress by storm - his caresses will be accepted with joy. That is, voicing the rules immediately simplifies the situation for all participants: the guy does not have to try to storm the girl’s honor, and the girl does not have to defend it. The threshold for the future exchange of caresses is predetermined.

You are wrong if you think that guys like to attack girls and get rejected. They will probably prefer to know the conditions of the game in advance: even if he needs to wait another 3-4-10 dates, he would rather do this than constantly pester and get rebuffed. Honesty and certainty are important.

When you have sex for the first time, the man is more worried than you.

Both of you are worried, not just you alone. He is no less worried than you are, and even more so - he may not be able to get hard, or it will all end in 5 seconds. You have nothing to worry about in this regard, except whether he wants to see you after the first sex. The less stress he experiences during his first sexual experience together, the greater the chance that everything will be great in the future.

And to be sure that the future will take place, emotional intimacy, or a sense of community and trust, is important. It takes different people different amounts of time to connect with another person on an emotional level: while others don’t even need a year.

Why? Because they do not know how to control themselves and manage their thoughts, they are not able to open up to another person, remove their “protection”, they are accustomed to lying and pretending. Usually these people do not love and do not value themselves, so they are afraid to tell the truth and admit their desires, feelings, they have suffered too much in the past and are afraid that they will be deceived again.

It turns out to be a vicious circle: their closedness prevents them from establishing full contact with another person and understanding his true intentions, so they waste a lot of time on liars who tell them the right words that they want to hear, but in fact, they are just trying to use them again. At the same time, they miss out on good men because they themselves deceive them about their needs and intentions.

Really loving relationships are built on the strong physical attractiveness of partners for each other, crazy chemistry, and not at all on the desire of one to intercede, and the other to receive material compensation for the act of love. A girl in love herself wants intimacy, kisses, hugs. Lover - wants to make sure that the man has spent enough money so that he does not have enough for another lady, and as proof of his “sincere” interest.

Truly loving relationships are built on strong mutual attraction.

How would you feel if, instead of being interested in your appearance and character, the candidate was more interested in your salary and the availability of an apartment and dacha?

Even if great feelings were not realized in your ideal union in the past, the lack of feelings and the desire to “sell yourself at a higher price” will lead you into an even greater dead end, from which it will be difficult to get out.

Without sexual chemistry, you won't last long in marriage. Over time, you will get tired of faking orgasms, and you will begin to look for reasons to refuse to perform “marital duties.” Your husband will be offended and think that you used him to immigrate. He will have a desire to take revenge and somehow punish you for deceiving and wasting his irreplaceable years of life. It is difficult to predict what this will lead to, but it will certainly not lead to anything good.

The humorous 3rd date rule says, “If she hasn’t kissed you by date 3, she’s here for the food.”

If you don’t feel the desire to kiss and hug a man by the 3rd date, if you absolutely cannot imagine yourself in bed with him - you don’t need “more time” at all to “start trusting” him - you need to gather your courage and confess to him and yourself that you are not in love and are unlikely to fall in love. If there is sympathy, if this does not happen, you do not have physical attraction to him.

If you know about your problem with trust in relationships and weak sexual arousal, try to regularly imagine yourself in bed with this candidate, how he touches you, kisses, hugs, takes off your clothes, mutual bodily caresses during sexual intercourse. How does this make you feel? If none or negative, you know this relationship is doomed.

Remember the man with whom you had crazy love and sexual chemistry. This is what you need to look for, only with a different character, more suitable for a faithful and loving husband.

I'm decent

I recently received a letter through the comments from a girl who angrily claims that “she’s not like that” and after 3 dates she’s not ready to make love.

I’m decent, so a man should provide and spend money, but we’ll wait with sex.

“This state of affairs is insulting to me. And it doesn’t matter whether they pay for me or not, even if I really like the man, I won’t go to bed with him on the third date. That’s either how I was raised, or maybe that’s just how I am. This is not for you to dance! I’m not going to change myself, even though I’m not a girl for a long time, and I have a child. And I can remain faithful for a very long time, even in the absence of a man, while having a hot Ukrainian temperament. And I will become closer to someone only after I understand that we can be connected by something more than sex. At the same time, I need to get to know the person, his lifestyle and, at least a little, gain trust in him, and make sure that he is not looking for girls for one night... and I consider it impossible to do this in three meetings.

And children, why does everyone spit at their mother’s status? So how can I not pay attention to the wealth of a foreign man if, when I move to him, I will be completely dependent on him for the first couple of years in a foreign country, and this is if I don’t think about having children together? In general, I think the article is one-sided, exaggerated and offensive towards all girls and women who do not want to be a man in a skirt.”

In general, “I’m decent,” so the man should provide, spend money, and I will “study” him until I decide that he has earned access to the body.

And everything seems to be fine, but one thing is missing - understanding the situation when communicating with foreign men via the Internet, when just to meet you, they have to fly thousands of kilometers and spend thousands of dollars.

Let's take a deeper look

With all this, the author of the comment has a small child and has never been married. This is not a problem (even positive for finding a husband abroad; there will be no puzzles with taking a child abroad if the child officially does not have a father) - the problem is a lack of understanding of men in general and foreigners in particular.

The expression “to start a family” in English means “to make new children”, and not legal marriage.

The lady’s profile is replete with the expressions “create a family”, which in English means “to make new children” - and not at all an official marriage. At least all seekers of foreign princes should know this difference.

The girl herself is attractive and has a good chance of finding a suitable partner abroad, but her position in the relationship can greatly hinder her.

Imagine, a wealthy man, in her understanding, should come to visit her for the bride, but he should not count on affection. Offended by fate, she is afraid of becoming a victim of a “one-night stand seeker.” Therefore, a man needs to demonstrate himself for a long time and prove that he is worthy of access to the body. 3 meetings are not enough for her.

In the profile, of course, there is not a word about this - only big words about finding your soulmate and love, the importance of family.

If a person has such strong views about how courtship and long-term abstinence from sex should work, why not be honest about what she wants from the very beginning? This will save long explanations and resentments in the future.

Of course, if an admirer comes to visit you, you don’t owe him anything - but inviting an admirer for a personal meeting when you are not yet sure that he is the person you need is rather ugly if it costs him at least a month salaries.

- If you need to know his lifestyle, ask questions. Ask to send photos and videos.

- If he spent many months communicating with you on Skype, 1-2 hours a day, he is clearly no longer looking for girls for 1 night.

- If you need to know that he will agree to provide for you and the child for at least 2 years after moving, then you should also say this right away, preferably in your profile.

This is where the problems come from - you write general words in your profile, and then start putting forward demands and conditions. Write immediately what you need- and you'll have a better chance of getting what you're looking for.

Be truthful with men if you want them to be honest with you.

What to write in your profile

Cliches about the importance of family, the search for a soul mate and love are a waste of advertising space. You only have 200 signs to hook a man with your uniqueness and enthusiasm. Repeating common truths that can be read in every female profile is boring.

The ability to create “sexual tension” already in correspondence helps inspire men to meet in person.

This is why men complain that girls write “the same thing” in their profiles; it is difficult for them to distinguish one woman from another, their descriptions of themselves are so similar.

Write interestingly. If you have certain ideas about how the courtship process should go, voice them right away. This can be an added advantage that makes you different from others. It's important how you express it - positivity will always win.

For example, if the girl’s statements above are true, and not feigned “decency,” then she should write like this (the first 200 characters of the message are visible immediately, to read the rest, the man needs to click on the button):

“I am looking for a partner for life, a lover, a friend and a husband all rolled into one. I like men who are firmly established in life and know what they want. I am attracted to smart and kind men. I have never been married, but I have a 2-year-old son for whom having a male role model in his life will be an opportunity to grow into a guy who sees loving relationships in his family and can find the same for himself in the future.

What you need to know about me: Sex for me is the highest expression of mutual love and trust, and I believe that getting to know each other and being able to trust a partner takes time. I am ready to spend this time getting to know my future husband in order to be sure that between us there is not only physical attraction, but also a commonality of goals and views. We will be able to get to know each other by communicating via Skype and email, exchanging photos and videos, and then in person.

I'm looking for a relationship for life. Therefore, I am ready to invest my time in getting to know each other, the lifestyle of my future partner and the possible place where I will move to live from my country. This is an extremely important decision for me, because I want to become a faithful wife to my beloved and only man.

For my part, I see myself as a housewife, at least until my son is 5 years old. I will be glad to create an oasis of comfort for my beloved man, surround him with care and love, cook him delicious food, be his domestic goddess.

I hope to meet a man who is close to my ideas.”

And in the “Requirements for a partner” block write:

“If you've read my profile and like my ideas about courtship and living together, I'd love to receive an email or expression of interest from you!”

If you are really afraid of having sex before marriage, you can write that you are one of those girls who believes in sex only after marriage (this is somewhat beyond the realm of reality if you have a child out of wedlock).

There are many men who are shy and don’t even know how to ask a girl for sex and what to do in bed, and have no relationship experience. So they will be glad to have the opportunity to meet a woman who does not expect lovemaking in the near future. Each message has its own audience.